John Sloan: American Modern

As a teenager in the 1960’s I found out about American artists like George Bellows, Stuart Davis, Robert Minor, Rockwell Kent, Alice Beach Winter, John Sloan, and many others whose works were based on social realism. Reading about these artists and their approach to art had a great impact on my own philosophy regarding the role of artists. I therefore encourage people to explore the life, times, and works of the aforementioned artists.

Today’s apathetic art scene would benefit greatly from exposure to America’s past school of social realism and its practitioners. So it’s wonderful to hear that Dartmouth College provided once such opportunity. Freedom Fighters: John Sloan and the American Moderns in the Dartmouth Collection, is the name of a slide lecture that art curator and scholar Mark D. Mitchell presented on May 20th at the Hood Museum of Art in New Hampshire. Mitchell’s lecture coincided with the currently running exhibit, Marks of Distinction: Two Hundred Years of American Watercolors and Drawings from the Hood Museum of Art, which includes artworks by John Sloan. Featured in the exhibit is one of Sloan’s most powerful pieces, simply titled Ludlow, Colorado, 1914.

On April 20th, 1914, Colorado National Guardsmen attacked an undefended striking miners tent camp in Ludlow with machine guns, slaughtering 20 people (thirteen of which were women and children). The miners were out on strike against the Colorado Fuel and Iron Company (CF&I) for better working conditions and union representation. The worker’s desire to join the United Mine Workers of America (UMWA) was opposed by the mine owners.

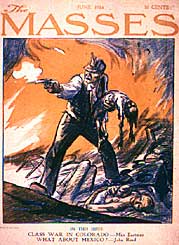

The mine owners used hired thugs, coal company guards and militiamen to assault the worker’s camp. The atrocity was quickly dubbed the Ludlow massacre and became a rallying cry for labor all across the United States. Sloan’s drawing, a thundering condemnation against the forces of repression, depicts a mine worker protecting the bodies of his slain wife and child.

He fires back at the paid assassins as the worker’s camp goes up in flames all around him. Sloan’s artwork first appeared as a cover illustration for the socialist newspaper, The New York Call, and it later became a cover for The Masses.

As it turned out, John D. Rockefeller, founder of the Standard Oil Trust, had twenty million dollars invested in the Colorado Fuel and Iron Company. Workers and labor activists in the US turned their ire against Rockefeller, seeing him as being responsible for the deaths of the innocent at Ludlow. Never had a tycoon been cast so low in the public eye, Rockefeller became a despised figure. The Cleveland Leader newspaper wrote, “The charred bodies of two dozen women and children show that Rockefeller knows how to win!”

The workers were defeated by Rockefeller’s bullets, but interestingly enough there was another, perhaps more important outcome as a result of the repression at Ludlow – the birth of corporate public relations. The Rockefellers hired Ivy Lee (considered the father of public relations), to clean up the image of the Rockefeller family. Lee published bulletins claiming the slain women and children at Ludlow died because an overturned stove set the camp on fire, and he made sure his fabricated story appeared in the press.

Lee worked tirelessly to plant pro-Rockefeller stories in newspapers and magazines, and he saw to it that only positive photos of Rockefeller were released to the public. Lee even came up with the idea of Rockefeller handing out dimes to the poor, with the benevolent gesture of course being photographed and published in the press. As a highly paid toady, Lee did not fool everyone. Famed poet Carl Sandburg said Lee was “below the level of the hired gunman.”

Upton Sinclair, author of The Jungle, simply called the Rockefeller sycophant, “Poison Ivy.” But Lee’s brilliant success at using PR to whitewash the Ludlow massacre was noted by others. He was hired in 1934 by the German Dye Trust, but his actual client was the regime of Adolf Hitler. Lee’s job was to favorably influence American public opinion of the Third Reich. His career ended in disgrace when the US Congress investigated his work for the Nazi regime, and then passed the Foreign Agents Registration Act in 1938.

Following the premiere of Marks of Distinction at the Hood Museum of Art, some eighty of the exhibit’s works will travel to the Grand Rapids Art Museum in Michigan (June 24th to September 11th, 2005), and then travel to the National Academy Museum in New York City, for a show that runs from October 20th to December 31st, 2005.