Jasper Johns: Target with Body Parts

I find an odd prescience in the “Target” paintings of Jasper Johns. While some gush madly over his works and others are simply indifferent – there is another story to relate, an untold chronicle that details the corporatization of American culture and the dumping of recent history “down the memory hole.”

Jasper Johns: An Allegory of Painting, 1955-1965, is a retrospective of Johns’s artworks running at the National Gallery of Art in Washington D.C. from January 28 to April 29, 2007.

The exhibit displays approximately 80 artworks; paintings, drawings, and prints. While Johns’s works facilitated the rise of pop, minimalism, conceptualism, and other genres found in postmodernism, that’s not what I want to address in this article.

Fifteen of Johns’s Target paintings are on view at the National Gallery, and arts writer for the New York Times, Holland Cotter, says they look “every bit as radical and mysterious as they surely did in New York in the 1950s, when, simply by existing, they closed the door on one kind of art, Abstract Expressionism, and opened a door on many, many others.”

Eerily titled Bull’s-Eyes and Body Parts, Cotter’s review touches upon more than a few sensitive issues:

“Art and crass are all but inseparable. So it’s no surprise to find an exhibition that brings together a record number of Jasper Johns’s famous target paintings being bankrolled by Target. You pass the corporate bull’s-eye logo, small but vivid, on a wall on your way into ‘Jasper Johns: An Allegory of Painting, 1955-1965‘ here at the National Gallery of Art.

Mr. Johns’s targets, endlessly reproduced in the half century since he painted the earliest of them, have themselves become a form of advertising, a logo for American postwar art. Through sheer omnipresence they’ve become nearly invisible. What could change that now?”

It’s not a happy accident that the first image seen at the Jasper Johns show is a corporate logo that echoes the artist’s most celebrated series of paintings, blurring the distinction between advertising and fine art.

No doubt the Target corporation is taking advantage of, and contributing to, the commercialization of culture. It should be remembered that the business practices of the Target corporation have attracted criticism, including its providing poor working conditions for American workers and using suppliers with links to foreign sweatshops.

Target is not only the official sponsor behind the Johns exhibit at the National Gallery of Art. It also sponsors the Museum of Modern Art in New York, underwriting MoMA’s “Target Free Friday Nights,” which provides free admission to the museum on Fridays after 4 p.m. Target also backs a similar program at the Los Angeles County Museum of Art called “Free after Five,” providing free admission to the museum throughout the week.

But it’s not my opposition to encroaching corporate control over the arts that drove me to write this article, it was the title of Holland Cotter’s review, Bull’s-Eyes and Body Parts, that prompted my response.

Whatever meaning that tiptoed behind Johns’s evocative targets in the past has since been superceded by unhappy real world events in the present – dealings that have much to do with actual targets and body parts.

For me, Johns’s paintings have become the phantom face of modern warfare – a wraithlike stand-in for a reality too horrific to cast one’s gaze upon. I had this epiphany regarding the works of Johns during the 1999 Kosovo/Serbia war – but it’s a certainty Cotter wasn’t thinking about that or any other war when he came up with his art review’s clever title.

My story brings to light a brilliant graphic symbol created and used in opposition to war, but it’s also a cautionary anecdote, as our collective amnesia has all but erased the compelling and historic symbol from memory.

Voluminous studies exist that analyze the 1999 Kosovo war and attempt to sort out the politics behind it, but presenting such investigation here is beyond the purpose of this web log, suffice it to say – I was against the war. Nevertheless, I’m astonished and dismayed that a recent conflict of such magnitude could be so easily forgotten… that’s what motivated me to write this.

First – just a fragment of background for context. The US says it led the NATO bombing of Yugoslavia in order to force the late leader Slobodan Milosevic to withdraw Serbian troops from the province of Kosovo, where thousands had been killed in a counter-insurgency war with separatist Albanian guerillas. Starting on March 24th 1999, NATO attacked Yugoslavia, carrying out 38,000 air strikes on the Balkan nation, roughly 700 sorties a day for 78 days.

The US was the dominant force in the NATO coalition, and it carried out most of the attacks. Around 20,000 so-called “smart bombs” were used, including dozens of cruise missiles and thousands of cluster bombs, which resulted in some 2,000 civilian casualties.

Even as the bombs and missiles rained upon Yugoslavia, President Clinton responded to the April 22, 1999 murders of 13 students at Columbine High School in Littleton, Colorado, by saying “We must do more to reach out to our children and teach them to express their anger and resolve their conflicts with words, not weapons.”

The very next day American cruise missiles slammed into the headquarters of RTS (Serbian state television and radio) in Belgrade (Beograd), the capital of Serbia, killing 16 journalists and technicians and maiming 16 others. Days later the Chinese Embassy in Belgrade would be hit by American cruise missiles, killing three embassy staff and injuring 20.

The Kosovo conflict became the first internet war, with all sides disseminating information and propaganda through e-mails and web sites. Serbian artists created and “digitally smuggled” antiwar artworks out of Yugoslavia, one such design being the target graphic.

I remember that it was a group of Serbian art students who were responsible for designing the antiwar symbol, but I haven’t the faintest recollection of whether they were living in the US or in Belgrade at the time. For now I’ll just say that an anonymous Serbian artist created the icon, uploaded it to the internet, and then untold thousands of people downloaded the image to print it out on home computers.

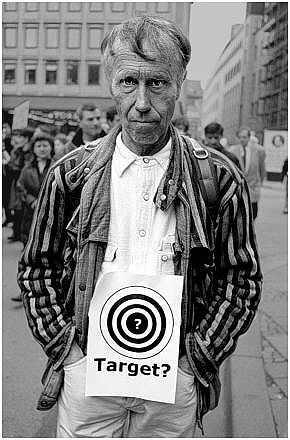

Just before the start of the NATO bombings, the civilian population of Belgrade, outraged and terrified that their historic city was about to be bombed, took to wearing xerox copies of the target symbol pinned to their clothing. My understanding is that the original black and white graphic consisted of a simple bold Bull’s-Eye, under which was printed the word, “Target.”

In next to no time variants of the design appeared, one version read “NATO Target,” another carried no words, but the center of the Bull’s-Eye featured a question mark. Printed in English, the target flyers were a clear attempt to reach a non-Serbian audience, and the news media inadvertently popularized the image while covering events in Belgrade.

Before long, the target symbol appeared at peace demonstrations around the globe, from Berlin and Paris to Los Angeles and Athens. Antiwar campaign buttons and bumper stickers bearing the graphic turned up everywhere.

The image was quickly replicated by those without computers or printers, and the icon was hand-painted and scrawled on tee-shirts, banners and placards. Soon thousands of civilians wearing or carrying target symbols gathered on the ancient bridges spanning the Danube River in a defiant effort to save the structures from NATO bombs. International television crews filmed those vigils and beamed the footage worldwide.

Once the aerial bombardment began on March 24th 1999, the crowds dispersed out of fear of being killed or injured, and fifty-five of Yugoslavia’s bridges would ultimately be destroyed by NATO bombs.

Eight years later the world has all but forgotten the brutal war over Kosovo, but every time I see one of Jasper Johns’s Target paintings, memories of that war’s savagery come rushing back, as well as anxiety over present-day belligerencies. Now that the West is embroiled in the even costlier bloodshed in Iraq, and with war on Iran looming over the horizon… it might be time to revive the antiwar target symbol.