“Apostles of Ugliness” – 100 Years Later

February, 2008 marked the 100th anniversary of “The Eight Independent Painters” exhibition at New York’s MacBeth Gallery. The event changed the face of American art and established the country’s very first avant-garde art movement.

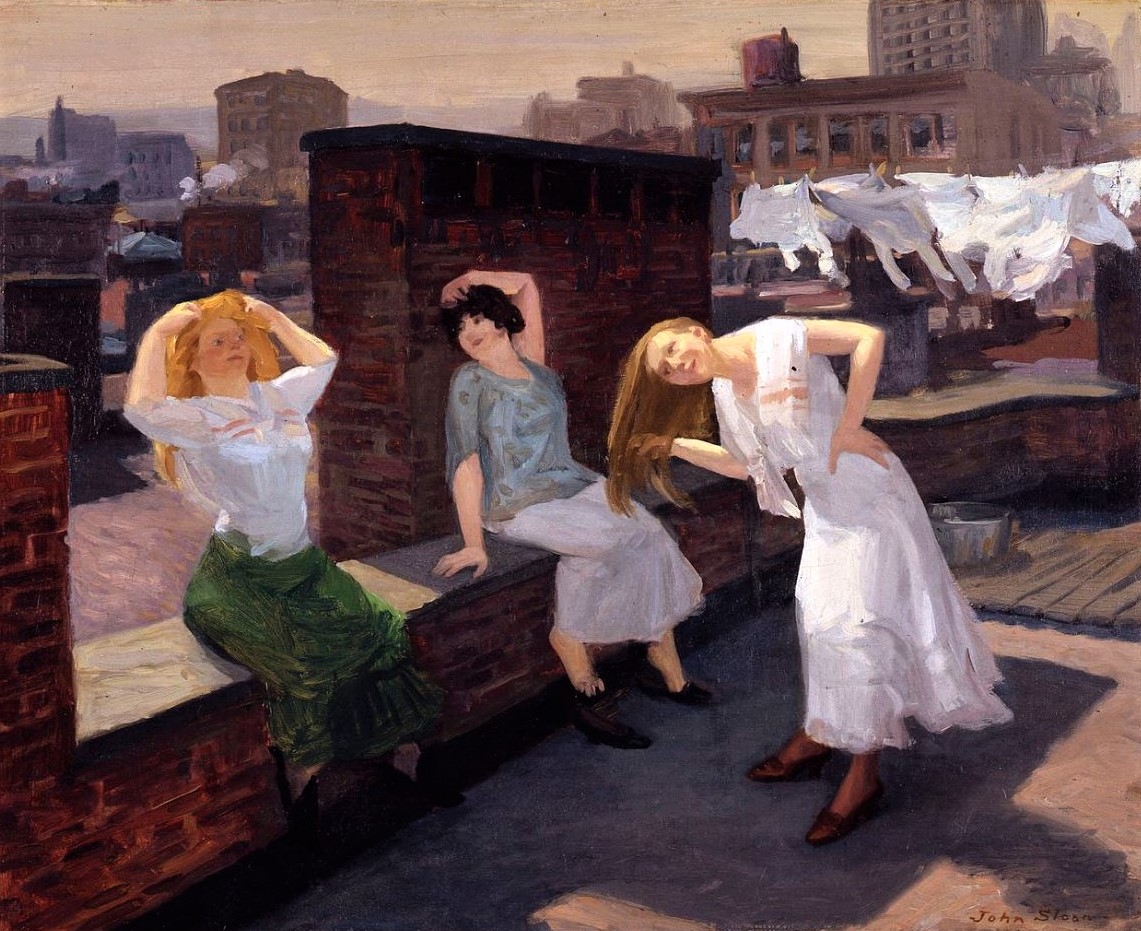

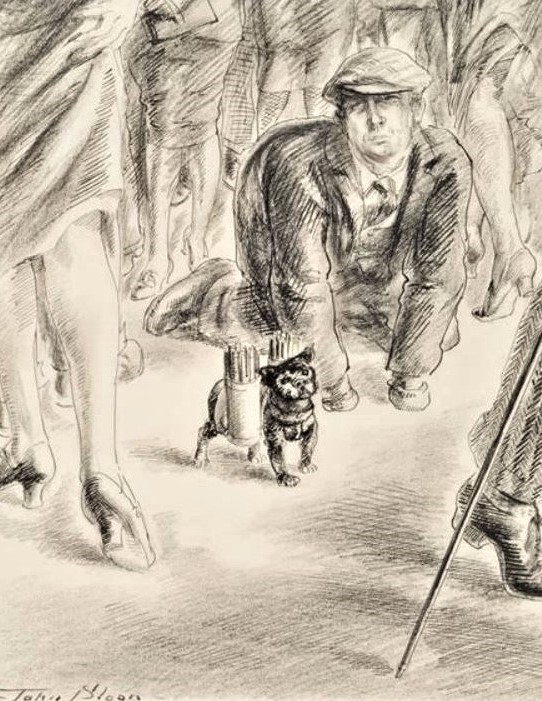

The Eight broke the rules of convention by painting the realities of New York’s working poor instead of the lives and accomplishments of the well-to-do class, but the centennial is not likely to receive any attention from an art world currently obsessed with escapism, celebrity and money.

In 1907 John Sloan, George Luks, and William Glackens were rejected for exhibition by New York’s conservative National Academy of Design, which slavishly upheld classical European academic painting. Robert Henri pulled his own works from the Academy exhibit in protest, and then set about mounting an alternative exhibition of works that would included artists hostile to the Academy’s entrenched academicians and their reactionary jury system.

Working with Sloan, Luks, and Glackens, Henri pulled together the exhibit at the Macbeth Gallery in February of 1908. Painters Everett Shinn, Ernest Lawson, Arthur Davies, and Maurice Prendergast were included in the loosely knit group – which became known as “The Eight Independent Painters,” or simply “The Eight.”

While multitudes flocked to the Macbeth Gallery to see the exhibit, the show was met with ridicule from the art establishment and derided by an unsympathetic press, which mockingly referred to the group as “The Apostles of Ugliness” or “The Revolutionary Black Gang,” since the artists painted working people and gritty urban realism with a somber palette. Eventually the group was contemptuously dubbed, the “Ashcan School,” a reference to the garbage cans found in crowded inner-city slums that served as backdrops for many paintings by The Eight.

The Ashcan school became the vanguard in the fight to modernize American art. Shockwaves created by the Macbeth Gallery exhibit led to further struggles against academic conservatism, opening the way to the famous 1913 Armory Show – which John Sloan and Arthur Davies helped to organize. The Ashcan school embraced progressive ideas put into motion by European artists, but reshaped those conceptions into something uniquely American. The Ashcan circle of painters eventually widened to include artists like George Bellows, Stuart Davis, Reginald Marsh, Edward Hopper, Rockwell Kent, and dozens of others.

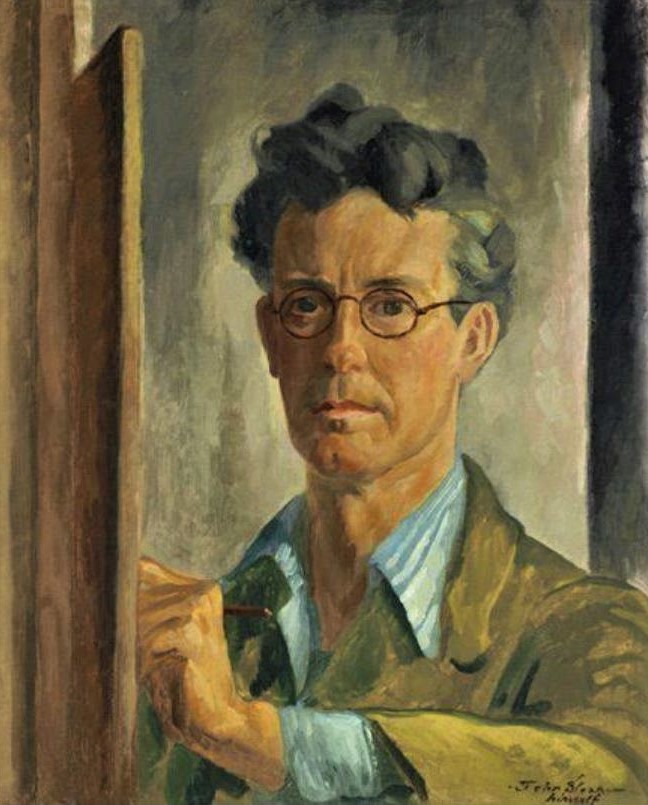

John Sloan was unquestionably the most politically engaged of “The Eight”, and his works and ideas have had no small influence upon me over the years. Accordingly, I’ll focus on Sloan for the rest of this article, especially since he is the focus of a magnificent comprehensive traveling exhibit organized by the Delaware Art Museum, Seeing the City: Sloan’s New York. The exhibit presents roughly 100 works by the artist, including paintings, prints, drawings and ephemera. Also check out the Delaware Art Museum’s John Sloan Manuscript Collection, which holds photographs, exhibit catalogs, and illustrated letters.

John Sloan’s ideas regarding painting, printmaking, and art instruction were fortunately preserved for eternity in a series of writings that were ultimately compiled as the book, The Gist of Art. Part personal observations on life and art, part instructional manual for those interested in the mechanics of drawing and painting, “Gist” is to a large extent comprised of verbatim notes taken while Sloan was teaching in the classroom or lecturing to an audience.

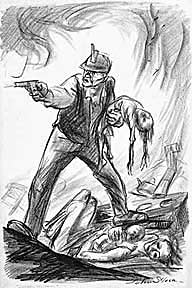

“Ludlow, Colorado.” John Sloan. Lithographic crayon on paper. 1914. Published as a cover illustration for the The Masses, Sloan’s artwork depicted the April 20, 1914 Ludlow massacre in Colorado. During a miner’s strike the National Guard fired on the striking worker’s tent city, killing 21 people – thirteen of them women and children. Sloan memorialized the bloodbath by depicting a miner, gun in hand, firing back at the Guardsmen who had killed his family.

Suffice it to say, I think everyone with an interest in the technical aspects of oil painting should read Sloan’s book, but the work also freely offers some of the philosophical ideas held by the artist, a few of which I’ll make mention of here. As an artist given to portraying everyday Americans at work and play, and as a member of America’s first avant-garde art movement, Sloan’s attitudes pertaining to patriotism were no less unorthodox than his views on art:

“In this relatively democratic country today, I feel that, since we can talk about things freely, we can go on painting any kind of subject matter we like.

It is not necessary to paint the American flag to be an American painter, as though you didn’t see the American scene whenever you open your eyes! I am not for the American scene, I am for mental realization.

If you are American and work, you work will be American. Patriotism, love of country, is very different from love for the government. I love the country in Pennsylvania, New England, and in the Southwest. I love the streets of New York. But I am suspicious of all government because government is violence.”

In a world so dominated by the logic of the market, we’ve come to accept sales price as the sole value of art, and we judge an artist’s success in terms of booming career and celebrity status, so Sloan’s views on making a living as an artist are a refreshing counterpoint to today’s money mad art world.

Sloan’s judgment of pursuing a career in art possesses an almost spiritual dimension, not in any religious sense, but in his understanding of art as something deeply personal and transcendent. I believe if we accepted Sloan’s outlook only in part, we’d all be much healthier for it:

“You can’t make a living at art. The idea of taking up art as a calling, a trade, a profession, is a mirage. Art enriches life. It makes life worth living. But to make a living at it – that idea is incompatible with making art.

Shun this idea of going into art with success as an aim, wealth as an aim, for the purpose of getting on in the world, getting the good things in life. Success has apparently become much more the art student’s aim than it was in my time. It spells disaster. No one who sets out for success gets the real thing. All you can get is a little sauce poured over you while you are alive.

There is only one thing to do about success – shun it. The only kind of success to desire is success with yourself. To make steps, progress, with yourself.”

Compared to the shallow art star celebrities of today, Sloan was well informed and showed not the slightest temerity in expressing controversial opinions. In the following he alludes to the first great world war that broke out in 1914, but his thinking clearly has meaning in the here and now:

“The governments are willing to turn their weapons, and tear gas bombs are the least of them, against the enemy or against their own people, their own citizens. Young people in their twenties are going to see things that I would like to live to see, and yet, it won’t be pleasant, it will be terrible.

I don’t like war. The economic interests get out their propaganda machines and persuade the people that democracy is at stake. And what do millions of innocent people go out and get killed and maimed for? To protect the economic interests of the few.

God must be awfully far away or disinterested to let people go on living the way they do in dirt and in filthy holes contaminating one another, swarming out to kill when ordered. They say that love makes the world go round. More likely, in our social set-up, it is the inferiority complex. It makes people want to get ahead, be important. The spirit of competition must be kept out of the artist’s mind.”

American social realism started to take shape at the turn of the century when the country was undergoing, much like today, an extraordinary economic and cultural transformation; which is what makes the Ashcan school so relevant for today’s artists.

Not just a cursory introduction to a long forgotten and marginalized American art movement, this essay is a call for a reassessment of the sensibilities and motivations found at the very core of the Ashcan School, that is to say, an unwillingness to succumb to the dictates of elite taste and fashion, a belief in artistic independence, and a passionate conviction that art should be grounded in the lived experiences of everyday people.

While the mainstream art world may pay little or no attention to the 100th anniversary of “The Eight Independent Painters,” those concerned with the present and future of art will want to look beneath the surface of things to study the Ashcan school and its lively anti-elitist humanism.