A Few Thoughts on Juneteenth

Now that Juneteenth has become the 12th legal public holiday in the United States, I have a few words regarding the jubilee commemorating the end of slavery in the U.S., that began when Republican President Abraham Lincoln issued the Emancipation Proclamation on Sept. 22, 1862. I will start this short essay with a comment on the Juneteenth Commemorative Flag, which undoubtably you will see a lot of in the years to come.

The Juneteenth flag was designed in 1997 by Ben Haith, founder of the National Juneteenth Celebration Foundation. Collaborators Verlene Hines, Azim, and Eliot Design, contributed to Mr. Haith’s vision of the flag, and the design was “fine tuned” by illustrator/artist Lisa Jeanne Graf.

Since Juneteenth began in Texas, the flag is evocative of the Lone Star State’s banner. According to Haith, the white star in the Juneteenth flag stands for Texas, but also for the freedom of blacks in all 50 states. The bursting outline around the star symbolizes a “nova,” or newly visible star—representing a new beginning for African-Americans in Galveston and across the US. The convergence of the flag’s blue and red fields into an arc indicates a new horizon of promise and opportunities for blacks. Haith says the colors of red, white, and blue represent the American flag, reminding everyone that the slaves and their descendants, were and are Americans, and that we must continue to live up to the American ideals of liberty and justice for all.

Some will think the Juneteenth flag a necessary symbol for an exceedingly important event in the nation’s life; I can appreciate that opinion while thinking the American flag already encapsulates those ideals. Others have rejected both flags, favoring instead the red, black, and green Pan-African flag of Jamaican-born black nationalist leader Marcus Garvey. Called “Black Moses” by followers, Garvey founded the Universal Negro Improvement Association (UNIA) in 1914, and envisioned Africa as a unified, black-separatist, one-party state to be governed by none-other than Garvey himself. I would look foolish waving the red, black, and green flag of Garveyism, so if you do not mind I will keep my American flag, and perhaps will acquire a Juneteenth Commemorative Flag as well.

As for Juneteenth’s origins, it all started with President Lincoln’s Emancipation Proclamation of 1862. The US Civil War began in April of 1861 and would not end until May 1865. On Sept. 17, 1862, the Union Army won a strategic victory over the Confederate Army at the Battle of Antietam in Maryland; five days later Lincoln issued the proclamation. While it officially outlawed slavery in the Confederacy—those states that seceded from the United States, it left slavery untouched in states loyal to the Union. However, the proclamation shifted the reason for the Civil War from a battle to preserve the Union, to one aimed at abolishing slavery.

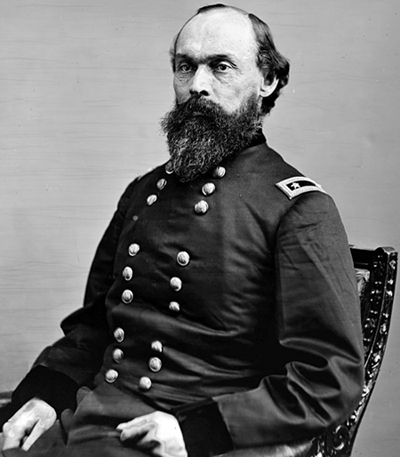

On June 19, 1865, Union Army Major-General Gordon Granger, accompanied by 2,000 Union soldiers, rode into Galveston, Texas.

They had orders to enforce the freeing of all slaves, nullify laws imposed by Confederate lawmakers, and see to a peaceful transition of power. Slaveholders in remote Texas had defied Lincoln’s Emancipation Proclamation, keeping 250,000 slaves in bondage.

Granger had the duty of reading General Order No. 3 throughout Galveston; it announced the Emancipation Proclamation and stated categorically that “all slaves are free” and as for masters and slaves, “the connection heretofore existing between them becomes that between employer and hired labor.” Union soldiers backed-up General Order No. 3 with bayoneted rifles.

For African-American slaves in Galveston on June 19, 1865, Juneteenth was Emancipation Day. Singing and shouts of Hallelujah! came from former slaves on the streets of the city that day.

The next day General Order No. 3 was published in the Galveston Tri-Weekly News. It was also reported on and reproduced by the New York Times on July 7, 1865. Recently the NYT published an archived copy of that report; everyone should read the order in its entirety. A year later mass organized celebrations began in Galveston and other cities in Texas. Over the years it became a grass roots celebration in black communities, particularly in southern states.

It is a sad state of affairs that many Americans have no idea what Juneteenth represents, or that its importance will be explained to them by corrupt corporate news media and demagogic politicians. It has been said that Juneteenth is the “longest-running African-American holiday.” I would correct that only by saying it is one of America’s longstanding celebrations, for what real American would not applaud the expansion of liberty? I view Juneteenth as a people’s holiday, hard won by the sacrifice of millions who struggled for liberty.

It must be stated that prior to the Republican government liberating the slaves in Texas on June 19, 1865, the U.S. Congress passed the 13th Amendment to the United States Constitution abolishing slavery on January 31, 1865. The vote was 68% for the amendment, and 32% opposed. Every Republican voted to pass the 13th Amendment. As for the Democrats, 50 voted nay, 14 yea, and 8 abstained. This fact should never be forgotten.

In celebrating Juneteenth as a national federal holiday, we should lionize those who made it possible. Abolitionists like Sojourner Truth, Harriet Tubman, Harriet Beecher Stowe, Frederick Douglass, William Lloyd Garrison, and Wendell Phillips. Black and white, these heroes embraced the liberatory struggle against human bondage, and their fearlessness helped to shape America.

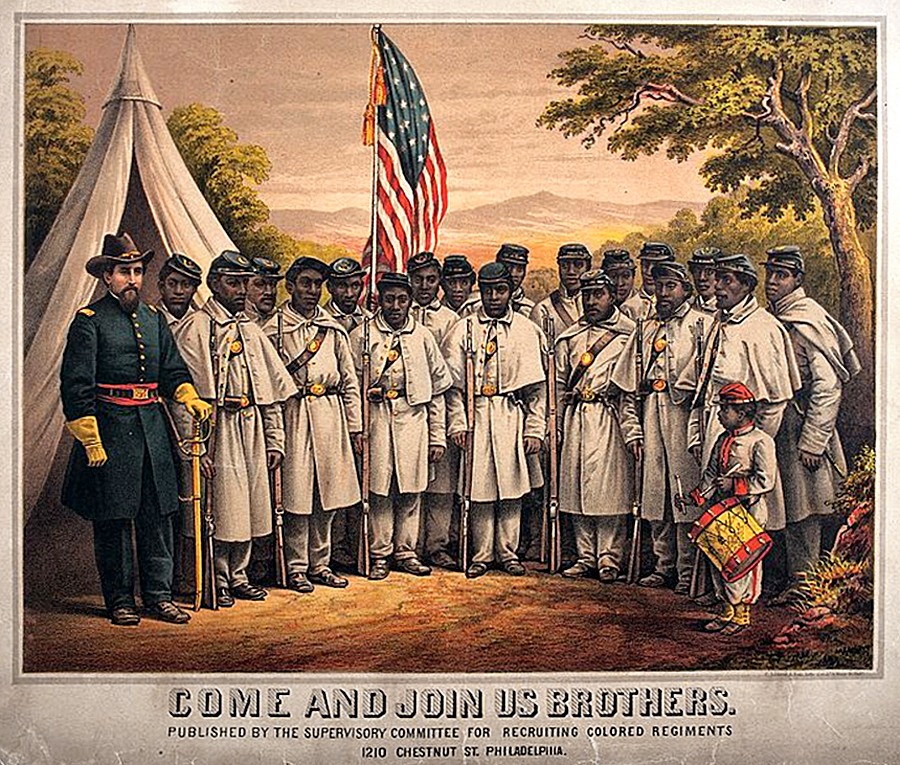

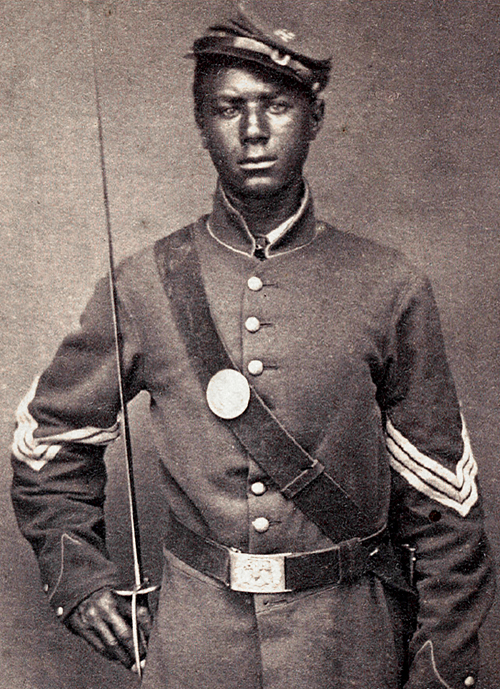

Never forget the gallantry of the Union soldiers, black and white, that forever changed the course of our nation. I place great emphasis on the black soldiers who joined the Union army to give their all in the fight against slavery. I have to mention Corporal John Payne of the 55th Massachusetts Colored Infantry. Payne wrote in 1862: “I am not willing to fight for this Government for money alone. Give me my rights, the rights that this Government owes me, the same rights that the white man has. I would be willing to fight three years for this Government without one cent of the mighty dollar. Then I would have something to fight for. Liberty is what I am struggling for; and what pulse does not beat high at the very mention of the name?” I praise the memory of Corp. John Payne, and hope to meet such men in our present.

As for heroics, Andrew Jackson Smith certainly qualifies. At nineteen-years-old he escaped slavery in Kentucky and eventually fell in with the Union’s 41st Illinois Infantry as a laborer.

Smith became the servant of Major John Warner; they agreed that in the event the Major was killed in battle, Smith would deliver his belongings to the Major’s family. Major Warner and the 41st took part in the April 5, 1862 Battle of Shiloh, and Smith found himself in the thick of the bloodiest battle yet fought in the war.

Confederates twice shot the Major’s mount from under him, and each time Smith provided the Major with another horse. Smith was slammed in the temple by a fragment of a “minnie ball” fired from a black powder rifle-musket. The fragment travelled just under his skin and stopped in the middle of Smith’s forehead.

Smith survived Shiloh, but when he heard that President Lincoln called on black troops to fight for their freedom, he joined the 55th Massachusetts Colored Infantry and became part of the color-bearer unit carrying the US flag and regiment insignia into battle. He fought the Confederates in multiple raids along the South Carolina and Georgia coasts.

Corporal Smith fought the Confederates at the Nov. 30, 1864 Battle of Honey Hill in South Carolina, where he showed great bravery. It was the third battle of Major General William T. Sherman’s “March to the Sea,” though Brig. Gen. John P. Hatch commanded the 54th Massachusetts and 55th Massachusetts black regiments in this particular battle.

During the fight the 55th’s Color Sergeant was obliterated by an artillery shell. Smith saved the Regimental Colors and continued the bloody attack, even as heavy grape shot and canister shells rained down on the Union soldiers from Confederate artillery. Half of the 55th’s officers and a third of the enlisted men were killed or wounded, but Smith continued to expose himself to enemy fire, never losing the colors to the enemy.

Corporal Andrew Jackson Smith lived to see the Confederate States of America vanquished and slavery abolished. After the war he lived in peace in Kentucky, where he died March 4, 1932 at the age of 88. The Medal of Honor was awarded Corporal Smith posthumously in 2001 for distinguished action and bravery at Honey Hill. It is appropriate for Smith to be remembered on Juneteenth.

Then there are the everyday black people, who over many decades observed Juneteenth with songs, prayers, food, and readings of the Emancipation Proclamation. They did so to keep the spirit alive, to remember those who sacrificed so much for freedom. They didn’t do it because Nike, Coca-Cola, Microsoft, Disney, and a bunch of opportunist politicians told them it was the correct thing to do. They did it for all the right reasons. Malcolm X once said, “History is a people’s memory, and without memory, man is demoted to the lower animals.” What he said conforms with the truth. Juneteenth is a people’s memory. Let us keep it that way.

I will close this essay with a tribute to those “everyday people” who kept Juneteenth alive. A few photographs from the Juneteenth Emancipation Day celebrations held in Houston, Texas in the early 1900s. It’s been a long time coming, but I know a change is going to come.