Woodstock Nation Gets Its Museum

I was only fifteen when the Woodstock festival was held, and naturally I dreamt of going, as did all of my friends, but I never made the trek. The event however had enormous impact that reached far beyond those who came together on Yasgur’s farm. The philosophy that was acted out there is perhaps best expressed in a quotation by a musician who performed at the momentous happening, Richie Havens: "Woodstock was not about sex, drugs, and rock & roll. It was about spirituality, about love, about sharing, about helping each other, living in peace and harmony." The museum aptly uses that quote in its promotional materials, and in part describes its mission with the following words:

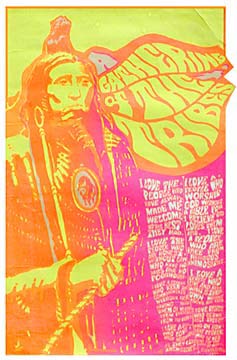

"The Museum embodies the key ideals of the era we interpret - peace, respect, cooperation and a connection to the planet we live on and all the people who inhabit it. In addition to preserving and interpreting an era, the museum is actively involved in our community - through education, economic development, and historical preservation - to encourage social responsibility among our visitors and supporters, and to advocate for issues that make Sullivan County, and the world at large, a better place. To borrow from 1960s ideology, everyone has the power to change the world."The museum’s permanent collection is divided into three parts, the first traces the earthshaking historic events of the 60s as the chaotic decade led up to the Woodstock festival - correctly placing the concert in the context of immense social upheaval. The second and largest section of the collection focuses on the festival itself - through displays of ephemera, photos, text and audio narratives, as well as interactive media presentations that culminate in a 21-minute film about the festival that includes Jimi Hendrix playing his awe-inspiring rendition of The Star Spangled Banner. The final portion of the museum’s collection covers the legacy of Woodstock, where amongst other things, those who attended the original festival can record their experiences for the institution’s archives.

The museum’s facilities are indeed impressive, and include a main exhibition hall that holds the permanent exhibit - consisting of over 300 photographic murals and text panels, 164 artifacts, five interactive media presentations, and 20 films. The museum’s theater offers seating for 132 people and a 13 by 22 foot screen with multi-channel sound and high-definition video projection. An outdoor theater seats 1,000 for special performances and forums, and starting in 2009 a Site Interpretive Walking Tour will show visitors the noteworthy spots on museum property - such as the location of the original Woodstock stage. A Special Exhibit Gallery where traveling shows from other institutions, collectors, and exhibitors can be placed on view is also part of the museum, together with a sizeable Events Gallery for meetings and receptions. Two large classrooms outfitted with audio-visual equipment are also incorporated into the museum, and naturally there is a museum gift shop.

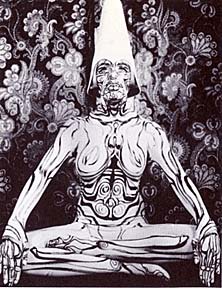

How accurate a picture of the Woodstock festival can one get from a family-friendly museum trying its best to avoid the controversies associated with the event - which was arguably the culmination of the most radical mass social experiment to have ever occurred in the United States? Two of the hallmarks of the Flower Power generation, "free love" - i.e., sexual liberation and promiscuity, and the use of psychedelic drugs to achieve "expanded consciousness", will most likely be downplayed by the museum, at least in its public presentations; yet these were driving forces behind hippie - effecting everything from clothing, language, music and art, to personal relationships and political stances. Serious research and scholarship should not be hindered by prevailing political moods, and to thrust aside troublesome facts in order to avoid upsetting the status quo is to rewrite history. Nevertheless, the Museum at Bethel Woods holds promise as an institution devoted to American history and social studies, in particular, the examination of the multi-faceted alternative culture that was hippie. Duly placing an emphasis upon educational resources and scholarship, the museum states:

"Adult learners and scholars can soon come to the museum for seminars and symposia to share their knowledge and add to the body of scholarship in areas of popular culture, mass media, and a variety of other subjects. In the future, the museum will soon provide opportunities for individual research, as well, through an expanded website, library/archive, and access to hours of recorded oral histories and volumes of photographs of the era."Nationwide and internationally there are many collections of 60s counterculture artifacts and ephemera held in private and institutional hands that could be brought together or linked in some manner - and the possibility that this might happen through the Museum at Bethel Woods is an exciting prospect. I hope that such relationships are developed and I encourage those with relevant collections and materials to contact the museum with ideas and proposals. The museum is also seeking relics from those who actually attended the Woodstock festival of ’69, as well as written, recorded, or oral histories from participants for possible inclusion in the museum’s permanent collection. All interested parties may contact the museum at: museum@bethelwoodslive.org. Visit the official Museum at Bethel Woods website.

Labels: Psychedelic Art