The Unveiling of Robert Scull

There are few independent observers of the art world who have not commented on the role money has played in shaping and distorting the arts in recent years. That reality was probably best expressed, inadvertently, by Tobias Meyer, Sotheby’s Worldwide Head of Contemporary Art and chief auctioneer, who in 2006 said, “The best art is the most expensive because the market is so smart.”

How did the contemporary art world become so single-mindedly venal and dim-witted? When did this downward spiral begin? Perhaps the following will shed some light on the matter.

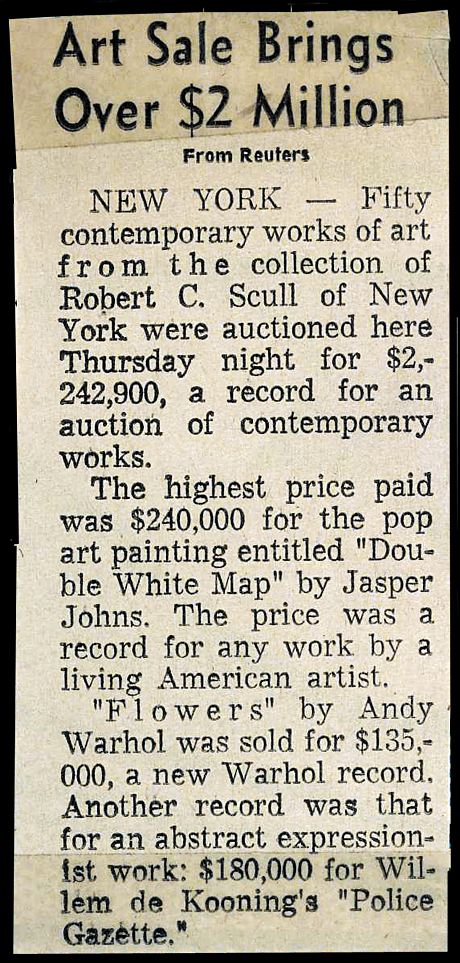

The other day I pulled an art book from off my dusty book shelf, and opened it to thumb through its pages. To my surprise I found a long forgotten newspaper clipping I had slipped into the book in 1973. Folded and yellowed, the cutting was titled, Art Sale Brings Over $2 Million, it was a Reuters news report published in the LA Crimes that recounted an event that shook the art world.

As I read the crumbling newsprint a flood of memories came to me, and I suddenly remembered the moment I became aware of money as an overbearing influence on contemporary art.

I was raised in the midst of the Pop art boom of early 1960s Los Angeles. As a twelve year old I went to the Los Angeles County Museum of Art in 1966 to see Back Seat Dodge, the outrageously controversial installation by Pop extraordinaire, Edward Kienholz (who by the way is still a favorite artist of mine). By 1970 I was questioning Pop and the art world in general, it was after all the late 60s, when young rebels asked difficult questions.

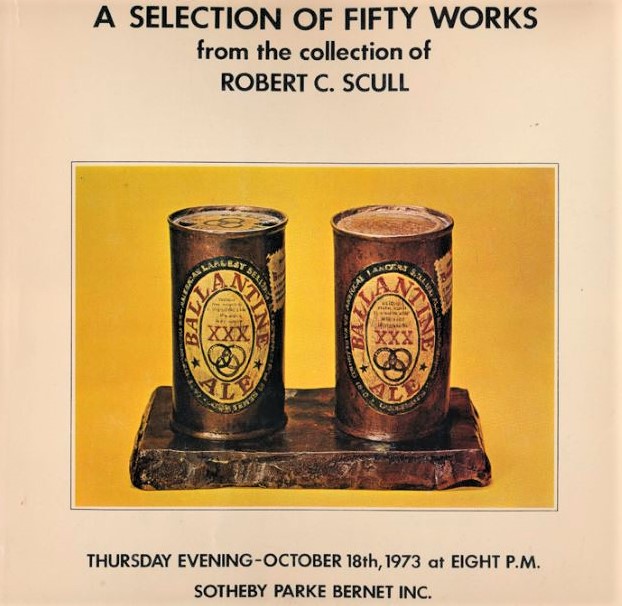

My disenchantment with the art establishment came in 1973 when New York taxi company mogul Robert Scull auctioned off a portion of his Pop art collection at Sotheby’s New York. The notorious Scull auction was a milestone event for contempo art; it heralded the commercial success of Pop, but more importantly, it affirmed the role big money would have in shaping and dominating the art world in the later 20th century and beyond.

The Scull auction and the events surrounding it were captured on film in an amazing and rarely shown 1974 documentary titled, America’s Pop Collector: Robert C. Scull – Contemporary Art at Auction, created by filmmakers John Schott and E.J. Vaughn. That same year the New York Times reviewed the film, saying: “You may be glad that you don’t paint, sculpture, own, sell, or buy contemporary art – which appears to addle many who come in contact with it.”

While the modern art critic and historian, Barbara Rose, wrote a scathing report on the Scull auction for New York Magazine, titled, Profit Without Honor, I first heard about the controversial auction by word of mouth, as it was a hot topic in artistic circles.

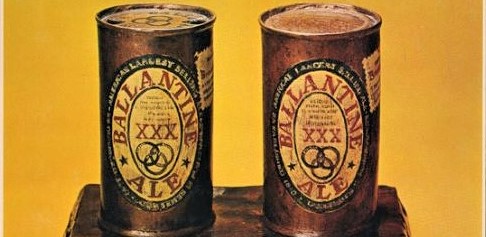

Scull had purchased early works from Pop artists who could barely make a living at the time, building a huge collection in the process. He bought a bronze cast of two Ballantine ale cans by Jasper Johns for $960, and sold them at auction for $90,000. He bought a painting from Robert Rauschenberg for $2,500, and sold it for $90,000. He bought a painting of flowers by Andy Warhol for $2,500, and sold it for $135,000. Overall, fifty pieces sold at the auction, bringing in $2,242,900, which was an astronomical sum in those days, and the increased value went, not to the artists… but to Scull.

In Schott and Vaughn’s documentary Scull remarked onscreen, “Acquisition is involvement, and in art, it’s probably the most exciting kind of involvement,” which was a shocking statement for the period, but one which wouldn’t even raise an eyebrow in today’s money besotted art world.

After the auction an outraged Rauschenberg took a swing at Scull, hollering, “I’ve been working my ass off just for you to make that profit!” But taken as a whole, the raise in prices increased the marketability of Pop artists who began to grow quite wealthy.

When Sotheby’s New York first announced the auction, many people were furious with Scull’s profiteering and the auction house’s blatant exploitation of artists.

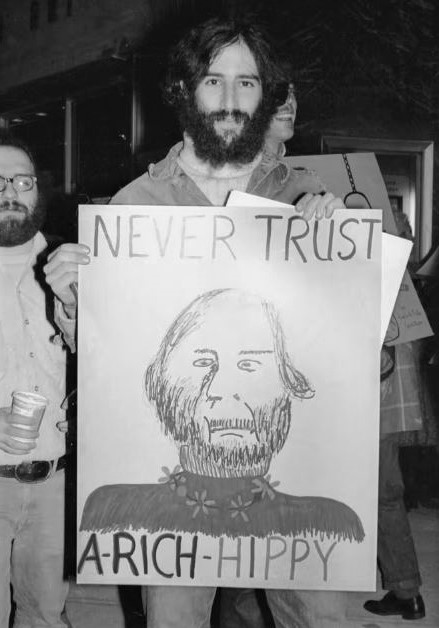

Remarkably, local artists and activists organized themselves to protest outside the entrance of Sotheby’s, greeting collectors with chants, banners, and picket signs that poured scorn on the notion of art being only for the privileged few.

Schott and Vaughn’s film shows demonstrators using their bodies to block the entrance to Sotheby’s. One protesting group was the Taxi Rank-and-File Coalition, a group of New York Taxi drivers who wrote and acted in a street theater performance given outside the entrance of Sotheby’s.

Calling their play The Unveiling of Robert Scull, the cabbies handed out a mockish self-published program guide where they made their primary demand, “Every taxi a museum.” Notes on the back of the flyer read in part:

“So here we are, workers and artists, reminding all these fine folk gathered here just where all the things they’ve got are coming from. The needs of the people and the flourishing creativity of the human spirit can no longer be subservient to the insatiable greed and egomania of the rich.”

What’s worth remembering about the Scull auction, is not so much that it prefigured an era where high finance became a determining, if not crippling factor in the arts, but that artists and art lovers still possessed the will to resist the intrusion of big money.

If that spirit could only be rekindled today, it would go a long way in guaranteeing that money does not turn out to be the last word in giving ultimate meaning and validity to art.