Artists and the My Lai Massacre

The Vietnamese called it the “American War,” and on March 16th, 1968, the Americans of Charlie Company marched into the hamlet of My Lai on a “search and destroy” mission. The soldiers of Charlie Company were directed by Captain Medina, who had issued orders to raze the village.

Charlie Company encountered no resistance, but for 4 1/2 hours they burned down homes, poisoned wells, killed livestock and methodically slaughtered over 500 innocent women, children, and village elders. Victims were thrown down wells with grenades tossed in after them, scores of elderly women were shot in the back of the head at close range while kneeling and praying, there were rapes, one group of 80 villagers were herded into the village plaza and machine gunned.

US Army photographer Ronald Haeberle was assigned to Charlie Company and he documented the atrocity in a series of grisly photos. He later testified that he had personally seen around thirty different GIs kill around 100 civilians. Platoon leader Lt.William Calley ordered his men to shove approximately eighty villagers into a drainage ditch at the edge of the hamlet, and then commanded his troops to open fire at point blank range. A two year old boy who escaped the barrage of bullets began running away. Calley seized the child, tossed him into the ditch, and shot him.

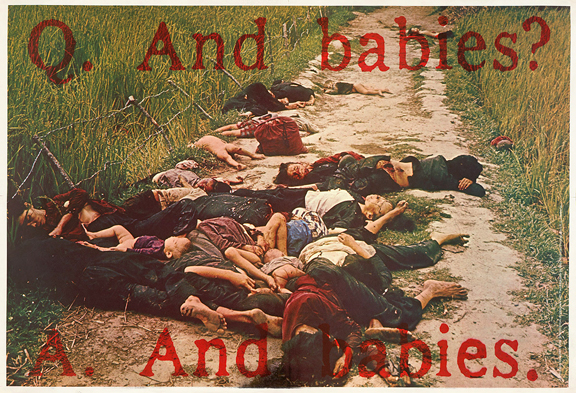

By November of 1969, Americans began to hear of the My Lai massacre. Life magazine published Ronald Haeberle’s gruesome color photos and the chilling images sent shockwaves around the world. The peace movement heightened its appeals to end the war. In 1970 the Art Workers Coalition, a group of New York artists, responded to events by designing a horrifying poster titled, “Q: And Babies? A: And Babies.” An anonymous creation at the time, the 24 x 35 inch poster was actually designed collaboratively by artists Frazer Dougherty, Irving Petlin, and Jon Hendricks. The poster used text from an interview by CBS reporter Mike Wallace with Paul Meadlo -a participant in the bloodbath, combined with a photo of My Lai’s butchered Vietnamese peasants taken by Haeberle.

The original poster was intended to be printed and distributed under the auspices of New York’s Museum of Modern Art (MoMA), until the president of the board of trustees rejected the idea. Nevertheless, the Art Workers Coalition raised the necessary funds to print fifty-thousand copies of the poster, which were then distributed internationally and carried in anti-war protests around the globe. I remember seeing the posters at rallies in my hometown of Los Angeles, which is how I acquired my copy.

To say that the artwork had an impact is an understatement, it became one of the most famous poster works from the Vietnam era. After MoMA declined to have anything to do with the artwork, the members of the Art Workers Coalition staged a demonstration at the museum, entering the room where Picasso’s Guernica was displayed to unfurl copies of their poster while reading anti-Vietnam war statements.

Medina and Calley eventually underwent a US Army court-martial. Medina was acquitted but Calley was found guilty in 1971 of “premeditated murder” and given a life sentence. Some in the US organized “Free Lt. Calley” protests and opinion polls indicated a majority thought Calley “was only following orders” and should be released. Pulitzer Prize winning cartoonist, Paul Conrad, summed up this shameful US grassroots support for war crimes in one of his trenchant cartoons.

President Nixon ordered Calley removed from prison and placed under house arrest. In 1974, the Army released Calley on parole. Today in Vietnam the old village of My Lai is a National War Memorial. Dotting the grounds are statues designed by massacre survivors to commemorate the victims. Plaques mark the earth where individuals or groups of people were put to death, and every March 16th, hundreds of Vietnamese trek to the memorial to place flowers on the mass graves and to offer prayers.

UPDATED 12/17/2016: Larry Colburn, the 18-year-old US soldier who attempted to stop the massacre, died on Dec. 13, 2016. He was 67. Mr. Colburn was the last surviving member of a three-man helicopter crew that placed themselves between innocent Vietnamese civilians and marauding US troops; Colburn was under order to fire his M-60 machine gun at US soldiers if they continued their slaughter. In 1998 Colburn received the Soldier’s Medal for lifesaving bravery. Read more.