Paul Gauguin: Writings of a Savage

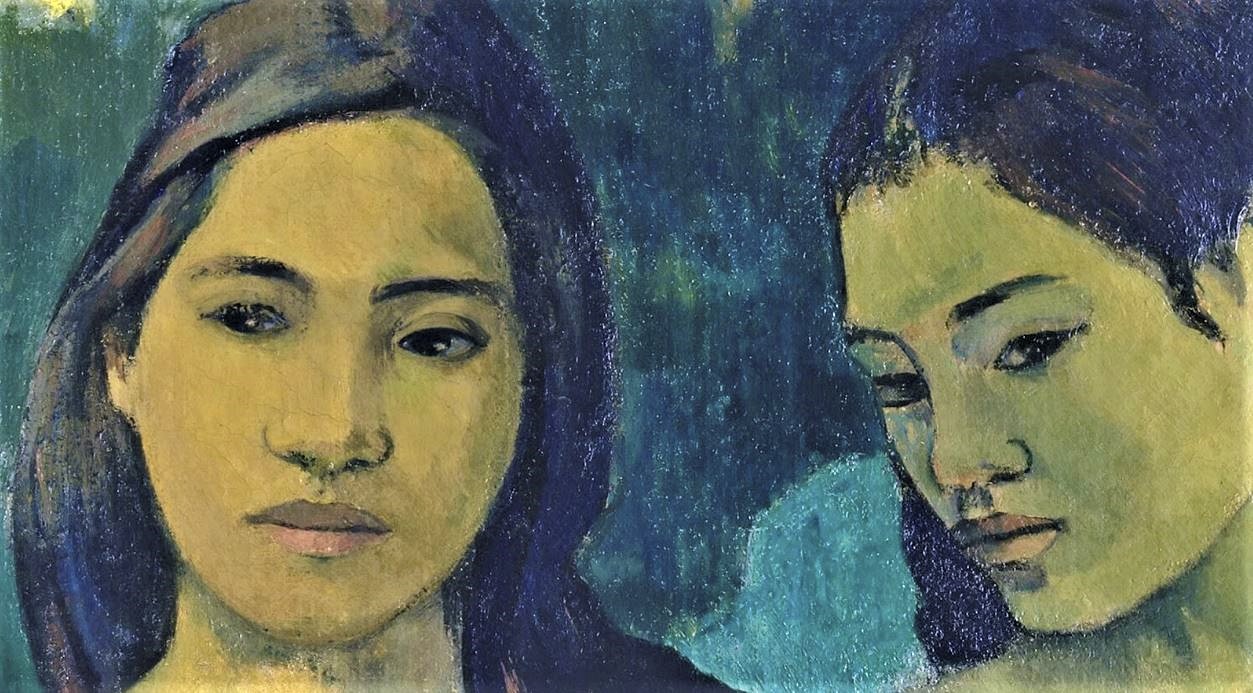

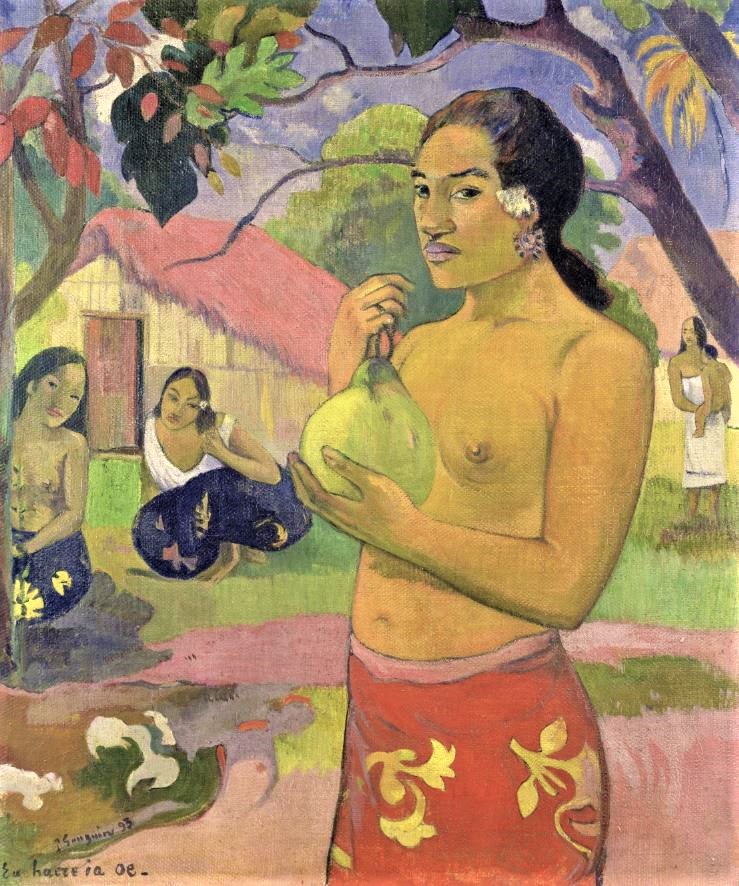

Lately I’ve been reading the autobiographies of artists from the past. In part as a defense against the trivial and insipid postmodern art world, but also as a genuine search for inspiration. Not too long ago I read Writings of a Savage by Paul Gauguin, and was struck by his eloquence and abilities as a writer. Gauguin was of course the artist who fled the city of Paris in 1891 for the tropical paradise of Tahiti. He had been enjoying a successful career as a stockbroker when he was exposed to Impressionism. He began painting on the weekends and became influenced by the Impressionist artists, Pissarro and Paul Cezanne.

His respectable income allowed him to purchase paintings by others in the Impressionist circle… Manet, Auguste Renoir, and Claude Monet. Ultimately he decided to toss aside his comfortable bourgeois career and give his all to painting. Gauguin thumbed his nose at the dominant world of academic art, all he wanted was to paint canvases that were true to his personal vision, paintings that would go beyond the traditionalist art of his day. But there was a price to pay, the same penalty every artist must shoulder when creating works that stand outside accepted boundaries. In his Writings of a Savage, Gauguin penned:

“I have known what absolute poverty means, being hungry, being cold… and everything that it implies. That’s nothing, or next to nothing; eventually you get used to it and with a little will power you laugh it off.

But the terrible thing about poverty is the way it prevents you from working, prevents development of your intellectual faculties. In big cities, and in Paris especially, you spend three quarters of your time and half your energy chasing after money. On the other hand, it is true that suffering sharpens genius. Yet too much suffering kills you.”

Those words are as true for artists today as they were for Gauguin when he wrote them. Too many of today’s living artists must contend with poverty and social indifference. Like so many other artists Gauguin died impoverished and unrecognized. He was buried in a pauper’s grave in his beloved French Polynesia. No one wanted his art. Only a few recognized his enormous talent – and most of them were fellow painters.

Gauguin would have been happy with a tiny monthly stipend, just enough to purchase paint and canvas and take care of the mundane necessities. But society ignored him, just as it ignores the gifted artists who stand among us today. In November of 2004, Sotheby’s auction house in New York sold Gauguin’s Maternité (II) for $39,208,000.

What would the artist have made of such ridiculous news? Without a doubt he would have asked why society did not support him when he was alive! In his Writings of a Savage he stated it plainly:

“I believe that in a society every man has the right to live, and to live well in proportion to his work. Since an artist cannot live, it follows that society is criminal and badly organized.”