Millard Sheets: The Early Years

Millard Sheets: The Early Years (1926-1944), on display at the Pasadena Museum of California Art (PMCA) through May 30, 2010, is an important exhibit of works by a leading California exponent of the “American Scene” painters, those artists given to documenting ordinary Americans going about their everyday lives.

Incorporated into the American Scene genre were the subcategories of “Regionalism” and “Social Realism.” The former concentrated on themes of local life in small town rural settings, the later engaged in works of social criticism, focusing on the experiences of working people in urban settings. Depending on the artist, there could be much overlap between the three schools, and Sheets was one to blend them without difficulty; Social Realism ran through his early works. Given my interest in that genre, and feeling it best describes what I am attempting in my own artworks, I enthusiastically attended the exhibition and now proffer the following comments regarding it.

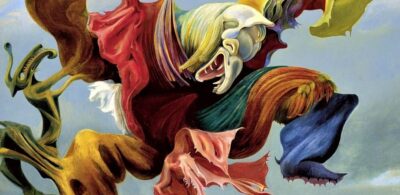

The first painting one sees when entering the museum is Abandoned, Sheets’ 1933 canvas that has come to symbolize the Great Depression. At first glance the focus of the work seems to be the wild and uncontrollable forces of nature, there is a spiritual quality to the painting, however, a second glance unveils an ominous, darker narrative. Under a forebodingly turbulent sky, horses move through a tangle of overgrown brush and fallen trees. The eye finally rests on a dilapidated windmill, and only then do the deserted farm buildings come into focus, as does the real meaning of the painting. It is a representation of American society brought to its knees by economic collapse, where even the family farm – iconic national symbol of self-reliance – has come to ruin. The mystical sense of the canvas dissolves into the brutal material reality that people were driven from the land and their properties repossessed by banks, a story that has once again become sadly familiar to millions of Americans.

Aesthetically speaking, Abandoned is a highly polished and sophisticated painting with a finish that displays few brushstrokes. It is a work that was planned out well in advance, despite its energetic and spontaneous look. Sheets eschewed detail to concentrate on form and composition, and here it is obvious that far from being a conservative painter, he was utilizing abstraction and Modernist aesthetics. One last note regarding Abandoned. While it is generally thought of as a Social Realist comment on depression era America, an interpretation I subscribe to, in reality the artist was inspired to create his canvas after seeing an abandoned farm in Riverside, California. The farm was marked for destruction so that the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers could build the Prado Dam flood control system.

Terminal Island Fish Harbor is a painting that immediately caught my eye. No reproduction could possibly do justice to this extraordinary work depicting a historic harbor near Long Beach, California.

Sheets managed to capture the fading light of a California sunset with incredible accuracy, the golden light illuminating a scene of fisherman at their work.

The dominant palette is hot; pastel yellows, oranges, and reds, brilliantly counterpoised by the cool blues of deep harbor waters. Despite the high degree of realism, a close up look at Terminal Island reveals a modern painterly approach, a detail in the upper left corner of the painting giving the best example of this. From a distance the wood buildings looming over the docked fishing boats seem almost photographic; a close examination however reveals heavy impasto layers of paint that have been incised with the sharp end of the artist’s brush, giving the illusion of weather worn wooden planks. I stood before this painting for the longest time, marveling at the artist’s technical prowess. It was my favorite work in the exhibit and well worth the price of admission to view all by itself.

Artistic virtuosity aside, the painting is astounding for another reason. With his canvas, Sheets captured an important and historic slice of life from Southern California. Terminal Island has a long history; for generations it was occupied by the Tongva/”Gabrieleno” Indians, in fact it was the Tongva who greeted the Spanish in 1542 when the explorer Juan Rodriguez Cabrillo landed in what is now known as San Pedro, California. When Sheets created his canvas in 1935, Terminal Island was almost entirely inhabited by first and second-generation Japanese, who had established a productive fishing industry there. In a 1977 interview conducted with the Oral History Program of the University of California Los Angeles, Sheets said the following:

“I spent a tremendous amount of time at the old Terminal Island fish harbor down in Long Beach, when they had a fantastic city of Japanese. There must have been 3,000 Japanese. Most of them couldn’t speak a word of English. They were all from Japan. All the customs and their festivals and the Sumo wrestlers, these marvelous big wrestlers that they had. I’ve seen all of the festivals down there. I used to see them three or four or five times a year, and I’d go down there and camp right on the dock. They all knew me, and I painted down there literally for years.”

In Terminal Island, the men on the docks pulling in the massive fishing nets were undoubtedly Japanese-Americans, but the vibrant community Sheets documented in his painting would met its doom just seven years after the artist finished his canvas. In the immediate aftermath of the December 7, 1941 bombing of Pearl Harbor by Imperial Japan, all Japanese-American adult males living on the island were arrested by the FBI. Subsequently, President Roosevelt issued Executive Order 9066 on February 19, 1942, which called for all persons of Japanese ancestry living in the U.S. to be locked up in “internment camps.” The entire Japanese-American community on Terminal Island was arrested, had its property seized, and was shipped off to prison camps. The traditional Japanese village on the island was entirely demolished, never to be rebuilt.

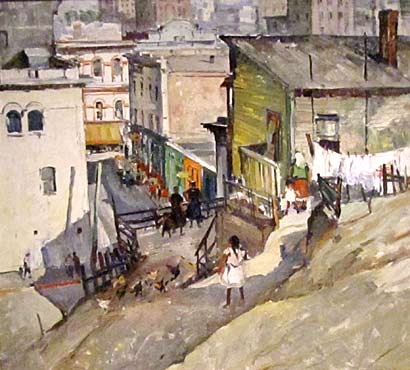

Also on display at the PMCA, the painting New High Street had great personal resonance for me.

It depicts a working class neighborhood in the old downtown area of Los Angeles that was bisected by New High Street, an avenue located between Sunset Boulevard and Temple Street, the vicinity where L.A.’s civic center would be built.

In fact, when Sheets painted this canvas in 1930, the construction of L.A. City Hall had been finished just two years earlier. The canvas shows an immigrant family’s old wooden house on a hill above New High Street, laundry hanging on the back porch and a little girl feeding chickens in the yard.

The reason I am fascinated with this painting – aside from its technical brilliance – is that my mother grew up in depression era Los Angeles. She lived with her mother, Anita Murieta, in a train boxcar parked on rented land in an L.A. suburb, where they grew vegetables and raised chickens to help make ends meet. Except for only slightly different circumstances and location, Sheets’ painting could have had my mother’s childhood as its theme. Everyday my mother’s mom would walk to the Pacific “Red Car” electric trolley station, riding the train to downtown L.A. where she would labor in the area around New High Street. Sheets’ painting echoes my own family connection to the City of Los Angeles.

New High Street is also a tour de force when it comes to direct “wet on wet” painting, and close scrutiny gives an idea of how the entire canvas was painted.

The little girl feeding the chickens was seemingly created from only two-dozen paint loaded brush strokes, applying only five colors (yellow ochre , cadmium red, burnt sienna, flake white, and ivory black). A single deft stroke of a brush laden with cadmium red and burnt sienna produced the girl’s arm, likewise, expertly dragging a brush loaded with ivory black over a wet field of white mixed with burnt sienna, produced the child’s pigtails.

This method tells you the canvas was painted spontaneously and on the fly, without a sketch or underpainting. Sheets’ had developed a personal calligraphic visual language that allowed him to create highly developed realistic scenes that were in actuality little more than short-hand oil sketches.

The painting Deep Canyon is related to New High Street, thematically as well as aesthetically. It is another of Sheets’ Social Realist examinations of poor working class neighborhoods. Keeping details to a minimum, the artist painted the urban jungle from brush strokes laden with paint, troweling on paint with a palette knife, and wiping, scraping, and incising the paint surface to various effect.

The use of color in this work is breathtaking; deep shadows in warm browns are sharply contrasted by bright hues of red, blue, and green; the skillful application of paint giving the illusion of sunlight streaming through concrete canyons.

The painting is full of movement, from the roiling storm clouds and laundry flapping in the wind, to the frenetic gestures of shoppers and vendors on the avenue.

As with New High Street, there is a remarkable lack of detail to be found in the impressionistically painted Deep Canyon, which in no way impedes the work’s narrative or emotive qualities. While there are a number of people in the scene, none have been painted with facial features – save for the woman carrying chickens in the lower left corner, and her face is blurry and nondescript.

Sheets’ handling of the people in his canvas is a skillful blend of caricature and humanistic concern. The rotund women on the stoops in the lower right of the canvas would be comical in appearance, save for the fact that the artist painted them with empathy and somehow imbued them with dignity. The groups of people gathered around the vendor in the green dress are composed of rapid brushstrokes and daubs of paint, yet they convey much life and energy.

Clearly Sheets was inspired by Cliff Dwellers, a depiction of crowded tenement housing on New York’s Lower East Side that was painted some 17 years earlier by the celebrated American Social Realist, George Bellows. Unfortunately, the PMCA provided no information about Deep Canyon, the painting’s caption listing neither the date of its creation nor the name of the locality the artist depicted – but I would venture to say it was not a painting of a Los Angeles scene.

Sheets’ Deep Canyon is a far cry from his Tenement Flats, painted in 1933-1934 and not included in the PMCA exhibit. A Great Depression era look at the poor working class neighborhood of Bunker Hill in the downtown area of Los Angeles, the canvas is painted in a strikingly realistic style, and the painting’s every detail, from the porch railings to the patterns on the laundry hung out to dry, was treated with equal attention by the artist. Tenement Flats is also notable for its underlying geometric composition, a nod to the Precisionist art movement – revealing once more the artist’s embrace of Modernist aesthetics.

The larger part of the exhibition is dedicated to Sheets’ watercolor paintings, works that brought him much praise and recognition during his career. Sixty of these watercolors are on display at the PMCA, and they are consummate examples of the discipline of watercolor painting. In these delicate works the artist celebrated the glories of America’s natural wonders in a rapturous, almost paganistic manner, with most of the watercolors recording the splendors of California; massive rolling hills depicted as the very embodiment of the “earth mother,” horses frolicking on abundant plains under expansive skies, the shimmering ocean kissing the craggy coastline – all conveying timelessness and a sense of boundless freedom. Never far behind the artist’s exultant observations of nature was an unshakable humanism, and so a number of his watercolors show people working the land as farmers or as immigrant laborers.

Watercolor paintings on display at the PMCA like Siesta Under the Trees (1936), Camp Near Brawley (1938), and Migratory Camp Near Nipomo (undated), attest to the exploitation of migrant workers in California agriculture. Sheets sympathetically depicted Mexican immigrants and “Okie” migrant workers escaping the Dust Bowl of Midwestern U.S. states, at their backbreaking labor in agricultural fields and at rest in makeshift camps. Sheets’ large watercolor titled Farm Workers is the most hard-hitting of these, portraying impoverished male and female migrant workers in the fields carrying heavy burdens of harvested vegetables under a punishing sun – the exact same painting of California agricultural workers could be made today.

Sheets also traveled to Mexico where he painted village life and landscapes in watercolor. The PMCA exhibit includes three of these works, and here again; the paintings have personal resonance for me. Sheets visited the coastal city of Guaymas, Mexico, in the state of Sonora, where he painted the watercolors. One in particular, Sunny Day in Guaymas (1932), is an enchanting painting that shows a woman wearing a traditional “rebozo” hand-woven shawl. She walks against a back drop of craggy hills, cactus plants, and adobe homes, the same scenery common to historic Los Angeles. That my father was born in Guaymas, and as a two-year-old migrated with his family to San Diego, California, six years prior to Sheets painting the watercolor – completes the picture for me.

Sheets had high regard for the Social Realist artists of Mexico, though he did not share their political radicalism. He said of the Mexican Mural School; “I’ve always been more than excited, just tremendously moved by it.” He had personally met many of the top painters, Diego Rivera, José Clemente Orozco, Rufino Tamayo, and David Alfaro Siqueiros. In fact, Sheets was one of the artists who assisted Siqueiros in painting his Worker’s Meeting mural on an outside wall of the Chouinard School of Art in Los Angeles in 1932, when Siqueiros was briefly in the U.S.

The PMCA exhibit is not without problems, it starts with the assumption that the public is familiar with the life and work of Sheets – if only that were the case. The most discernible problem is the museum’s negligence to provide adequate captions for the works. The majority of labels give no information beyond title and medium, managing even to write “date unknown” on several pieces where the artist clearly signed a work with a legible date. Historical information needed for a full understanding of the artist’s works – and his place within his era – could have been provided as short, concise, paragraphs. The museum catalog for the exhibit, written by its curator, Gordon T. McClelland (an acknowledged authority on California “American Scene” painters), somewhat makes up for this omission, but museum goers should not be required to purchase a book in order to understand an exhibited artist.

Sheets accomplished much during his lifetime as an artist, and the PMCA should have done more to provide insight into his life’s work. That being said, Millard Sheets: The Early Years (1926-1944), is an exhibition not to be missed.