Peace Press Graphics 1967-1987: Art in the Pursuit of Social Change

I am pleased to announce that a number of my early graphic works have been included in the museum exhibition, Peace Press Graphics 1967-1987: Art in the Pursuit of Social Change, organized by the University Art Museum at California State University Long Beach (CSULB). The exhibit is part of the Getty Foundation’s Pacific Standard Time: Art in L.A. 1945 – 1980, the largest collaborative art project in Southern California history. I have six artworks in the exhibition, and four additional graphic works in the exhibit catalog, but in this article I am going to highlight a Peace Press published work of mine not included in the show. In weeks to come I will upload more of my Peace Press images and bring their histories to light in a detailed essay.

Peace Press Graphics is an important showing of over 100 historic posters and flyers published by Peace Press, a now defunct Los Angeles collective that ran a professional print shop serving the local and national needs of left-wing political groups and organizations. The published works on display, culled from the archives of Peace Press as well as from the collection of the Center for the Study of Political Graphics (CSPG), address a wide range of topics – civil liberties and human rights, worker’s issues, feminism, environmental concerns, anti-nuclear and anti-war protests, and much more.

A number of posters in the show epitomize the psychedelic aesthetics of the late 1960s, works from the likes of Robert Crumb and Skip Williamson, exemplars of the 60s hippie counter-culture. Other posters embody the political militancy of the day, like Chicano artist Rupert Garcia’s Save Our Sister, a poster commissioned in 1972 by the Los Angeles Committee to Free Angela Davis. Taken as a whole the assortment of works on display form an accurate visual record of dissident cultural and political forces working within the U.S. from 1967 to 1987.

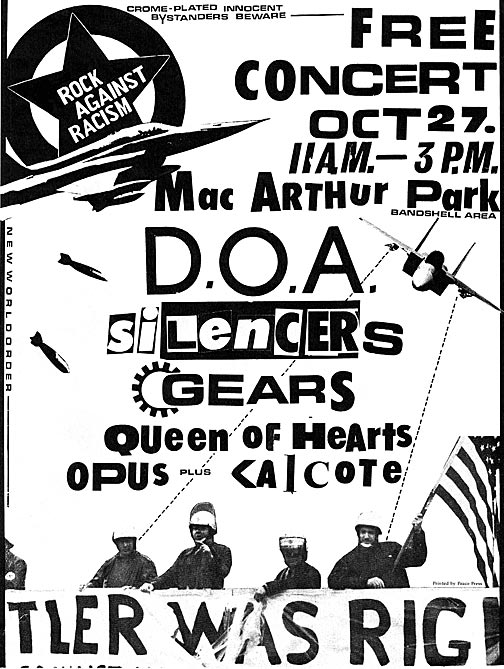

In the late 1970s and early 1980s I created a number of drawings and flyers as a direct result of my involvement in the early punk rock movement of Los Angeles. In true punk spirit my flyers were meant to provoke, and I generally produced and distributed them anonymously. One such example is the flyer I designed for the L.A. chapter of Rock Against Racism (RAR) in 1980, a rare leaflet that was published by Peace Press.

My Rock Against Racism flyer announced a free concert in L.A.’s MacArthur Park, held October 27, 1980 at the band shell area of the commons. The leaflet touted the appearance of the rough and tumble Canadian punk band, D.O.A., who were quite big at the time and remain one of my favorite punk bands. In the context of the museum exhibit the significance of this particular flyer is twofold. While Peace Press printed a number of posters and flyers for the likes of Jackson Browne, Joan Baez, and others associated with the counter-culture of the late 1960s and early 1970s, my RAR flyer is most likely the only punk graphic ever to be printed by Peace Press; the flyer also gives evidence of the progressive political side to L.A. punk.

My flyer was created before computers were used to generate graphic art. Utilizing the dread inducing “ransom note” visual language, the text, replete with intentional misspellings, was mostly produced by cutting letters out of magazines and newspapers with a razor blade, then gluing them down to a sheet of paper. The rest of the copy was created using the now archaic “transfer type” once so prevalent in the advertising industry of the day. News photographs were interspersed with the irregular lettering to construct an incendiary narrative. The photo at the bottom edge of the flyer shows American Nazis wearing crash helmets, waving a U.S. flag, and carrying a banner that brazenly praises Hitler; the timely photo being ripped from a then current newspaper report on a neo-Nazi rally in a U.S. city. Soaring above the scene, two RAR fighter jets unleash bombs and automatic cannon fire upon the gaggle of jackbooted fascists.

Founded in London, England in 1976, the launching of Rock Against Racism was concurrent to the emergence of punk rock in Britain, a movement that would explode upon the world scene in 1977 with the outrages of the Sex Pistols, the Damned, and the Clash. In the mid to late 70s social conditions deteriorated in the U.K., giving rise to openly fascist political organizations like the National Front; during this period neo-Nazi skinhead gangs unleashed hundreds of violent attacks against South Asian and Black immigrants across England.

As the National Front and neo-Nazi skinheads sowed mayhem throughout England, famed guitarist Eric Clapton added fuel to the fire at a U.K. performance in Birmingham held on Aug. 5, 1976. Clapton launched a harangue from the stage on the dangers of the U.K. becoming a “black colony.” He said in part; “This is England, this is a white country, we don’t want any black wogs and coons living here. We need to make clear to them they are not welcome. England is for white people, man. We are a white country. I don’t want f*****g wogs living next to me with their standards (….) Throw the wogs out! Keep Britain white!”

Needless to say the celebrated guitarist lost a substantial amount of his fan base over his diatribe. A month before Clapton’s concert a Sikh teenager named Gurdip Singh Chaggar had been murdered by a mob of white racists, the chairman of the National Front, John Kingsley Read, responded to the killing during a National Front meeting with the words, “One down, a million to go.”

Also in 1976, after a concert in Sweden, David Bowie made a statement to a Swedish reporter, saying: “I think Britain could benefit from a fascist leader. After all, fascism is really nationalism. I believe very strongly in fascism, people have always responded with greater efficiency under a regimental leadership.” Later on Clapton and Bowie profusely apologized for their statements; Bowie blamed his remarks on his cocaine addiction.

After Clapton’s concert shenanigans, photographer Red Saunders and designer Roger Huddle wrote a seething criticism that was published in the New Musical Express, an article I recall reading when it was first published. The irate Saunders and Huddle berated Clapton, “Half of your music is black. You’re a good musician, but where would you be without the blues and R’n’B?” They went on to proclaim, “We want to organize a rank-and-file movement against the racist poison in music. We urge support for Rock Against Racism.” Soon after the letter’s publication in August 1976, Rock Against Racism (RAR) was founded in the U.K. as an actual political/cultural organization that staged concert events. Tellingly, it was not rock’s superstars and corporate mainstream acts that collaborated with RAR, but rather the rebellious and lesser known ska, reggae, and punk groups that had nothing to lose.

On April 30, 1978, Rock Against Racism staged its Carnival Against The Nazis, a gigantic music festival presented in London’s Victoria Park. The performers included The Clash, X-Ray Spex, the Tom Robinson Band (the world’s first openly Gay rock band), Steel Pulse, and Aswad. The groups played before an enthusiastic multiracial crowd of some 100,000 people. The program for the event proclaimed; “We want rebel music, street music. Music that breaks down people’s fear of one another. Crisis music. Now music. Music that knows who the real enemy is – Rock against racism.” Soon after the Carnival Against The Nazis, RAR chapters began to proliferate.

To my knowledge, the Los Angeles chapter of Rock Against Racism did not operate for very long, but the group’s efforts undoubtedly contributed to the city’s history, as well as to the cultural and political activism carried out in the U.S. during the ultra-conservative Reagan years. I am pleased to take credit for this once anonymous flyer, an artifact from a bygone rebel social movement, and happy to reveal that it was published by Peace Press. With a bit of luck, it will help inspire future troublemaking. One can only hope.

Peace Press Graphics 1967-1987: Art in the Pursuit of Social Change, runs from September 10 to December 11, 2011 at the University Art Museum, California State University Long Beach.