Moody Park: An Untold Story

As an active participant in the original punk rock underground of 1977 Los Angeles, I created my fair share of subversive graphics designed to provoke the wider society. One arena of intervention I was involved with was the anonymous production of leaflets for mass distribution; some flyers promoted concerts, others were a “poke in the eye” aimed at an increasingly conformist society. In part, this essay is about one such handbill I designed in 1978, a crossover between benefit concert announcement and insurrectionist vituperation. But this article is also about larger issues.

Before I provide details on the flyer, it is necessary to look back at the incident in Texas that served as the impetus for the concert. Thirty-six-years ago the police in Houston, Texas murdered a 23-year-old Mexican American Vietnam Veteran named Joe Campos Torres. The murder shook the nation, reverberated through the decades, and continues to have relevancy in the present, though today most have never heard of the killing. In this article I will weave a story with threads of history while divulging my own unique connection to those days of old.

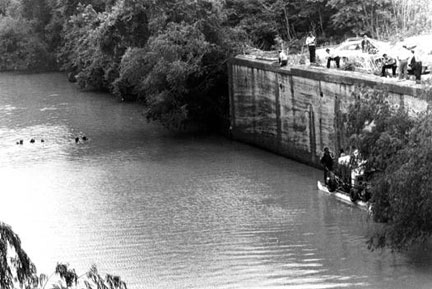

On May 5, 1977, six Houston policemen arrested Joe Campos Torres at a bar for disorderly conduct; he was wearing his Army issued fatigues and combat boots when arrested. Instead of taking him to jail, the cops dragged him off to “the hole,” an isolated area behind a warehouse along the Buffalo Bayou in Harris County, Texas. The cops beat the Chicano Vet to within an inch of his life, then they took him to the city jail. Torres was so badly injured that officers at the jail refused to process him, and ordered that he be taken to a nearby hospital; instead his tormentors took him back to the hole for another trouncing.

During the beating one of the six policemen, Officer Denson, said “Let’s see if the wetback can swim,” as he shoved Torres off the raised platform of the warehouse to fall twenty feet into the bayou. His lifeless body was found floating in the bayou on Mother’s Day, May 8, 1977.

Initially only two cops were put on trial for the killing of Torres. Officers Denson and Orlando were tried on murder charges and an all-white jury found them guilty of “negligent homicide” (a misdemeanor). Their sentence was one year probation and a $1 dollar fine! It should come as no surprise that across America in 1977 the word on the street became “A Chicano’s life is only worth a dollar.” There was so much public outrage over that phony trial that Federal charges of civil rights violations and assault were brought against all six officers. That “trial” resulted in all six receiving a ten year suspended sentence for the civil rights charge, and Denson and Orlando getting a nine month prison sentence for the assault charge.

The punishment for murdering a Chicano Vietnam Veteran went from a one dollar fine, to receiving a nine month prison sentence. Discontent simmered in Houston’s Chicano community for a year, until it erupted on the 1st anniversary of Torres’ outrageous murder.

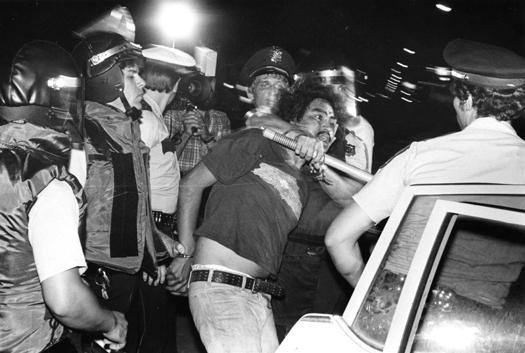

During the 1978 Cinco de Mayo (5th of May) celebration in Houston’s Moody Park, the police attempted to make an arrest. The crowd resisted the police move and began chanting “Viva Joe Torres” and “Justice for Joe Torres!” The melee turned into a full blown riot with waves of Chicanos hurling rocks, bricks, and bottles at the police, 14 cop cars were overturned and torched. The furious crowd surged out of the park and set fire to local businesses, as unidentified shooters took potshots at the police. In a 2008 interview with Houston Public Media, retired Houston police officer Harold Barthe said that “hundreds of people were chanting, ‘Joe Torres dead, cops go free, that’s what the rich call democracy!'”

Needless to say, the authorities responded with overwhelming force, sending in armed SWAT squads to quell the uprising while police helicopters filled the skies. In the end, dozens were arrested and 15 were injured; property damage ranged in the hundreds of thousands of dollars. It all became a story on Walter Cronkite’s CBS Evening News broadcast.

Here I must note that the African American bluesologist Gil Scott-Heron, memorialized Torres on his 1978 spoken word album The Mind of Gil Scott-Heron. The emotive track titled José Campos Torres combined a tender and ethereal jazz background with a calmly delivered yet fiercely angry contemplation on racism and police brutality in America. A beautiful act of solidarity with Mexican Americans, the song meant a great deal to us all in 1978; I must have listened to it a thousand times. For me, it set the tone for what an artist could do, not just regarding the murder of Torres, but in confronting social injustice of any kind. I wanted to contribute something as well, and my turn was just around the corner.

Of course the authorities needed someone, other than themselves, to blame for the Moody Park violence. They arrested three communist activists who had been active in the justice for Joe Torres campaign and charged them with “felony riot.” That trio became known as the Moody Park 3, and each faced a sentence of 20 years in prison.

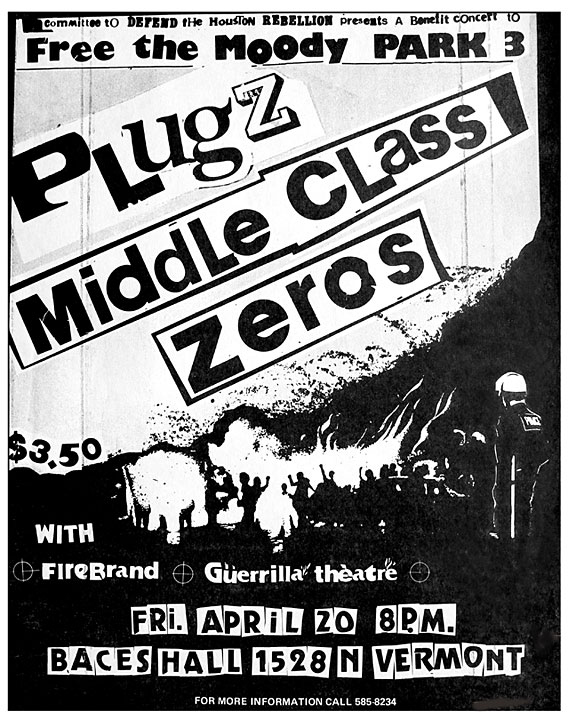

Groups like the Committee to Defend the Houston Rebellion started to hold events to raise legal defense funds for the trial of the Moody Park 3, one such event was a punk concert at the old Baces Hall in Hollywood. Frankly, I do not remember who asked me to create the concert announcement flyer, but knowing that three of my favorite Southern California punk bands had signed on to play the gig was enough to get me on board, that and my vexation over the murder of Torres.

I was not impressed with the ultra-left Committee to Defend the Houston Rebellion, in fact my only point of agreement with them was that the Moody Park 3 had been framed. The committee was new to punk and gravitated to it because of its reputation for rebellion, but it was clear that they did not know what they were getting into. It must be said that at the time punk was wholly repellent to the wider society, venues in L.A. had closed their doors to it, and it seemed the L.A.P.D. had made a hobby out of suppressing it. So I suppose the committee should get credit for being so bold, or is that reckless, for organizing a punk rock concert when few others would dare.

It goes without saying that I created the flyer in the days before computer technology. In true punk fashion the crude leaflet was made from newspaper and magazine clippings, combined with the use of rub-down letters and tone films from the Letraset company, supplies widely used in publishing at the time. Letraset also manufactured registration marks, which were used to help align colors and images; I used the symbols in my flyer to approximate the crosshairs of a rifle scope. Thousands of copies of the disposable mess were Xeroxed in glorious black and white.

Like most punk flyers from those fire-eating days, it was posted on lampposts and city walls. On the street it countered the babble of the city’s obnoxious merchandising billboards and neon signage. The flyer’s cryptic message was baffling, like some strange cabalistic language. Who on earth were the Moody Park 3 and what was the significance of the bizarre word combination – Plugz, Middle Class, Zeros? In 1978 the throwaway circular was an unsettling image to see on the streets. One must recall that the U.S. Billboard top 100 songs of 1978 included the likes of How Deep Is Your Love by the Bee Gees, You’re the One That I Want by Olivia Newton-John and John Travolta, and Boogie Oogie Oogie by A Taste of Honey.

The leaflet brought hundreds of punk rockers, mischief-makers, and juvenile delinquents to the tenebrous punk shindig. I want to make it clear that history has unfairly characterized the early L.A. punk scene as a movement of apolitical spoiled white kids from affluent communities with nothing better to do than cause trouble; the social phenomenon has been “whitewashed” and depoliticized. Sizable numbers of working class youth and minorities were involved in California’s agitated punk scene, including scads of Chicanos. The “Moody Park” punk concert at Baces Hall was evidence enough of this; there were not only Chicanos in the bands and in the audience, but the entire concert was a protest against the murder of a Chicano Vet in one of the largest Mexican American communities in Texas!

The Plugz were one of L.A.’s original punk bands, and two of their three members were Chicano. Their updated sonic rendition of La Bamba offered altered lyrics like the following, “Capitalistas, mas bien fascistas, yo no soy fascista, soy anarchista” (Capitalists, better yet fascists, I am not a fascist, I am an anarchist). La Bamba was actually a famous Son Jarocho folk song from Mexico’s state of Veracruz made famous in the U.S. in 1958 by Chicano rocker Ritchie Valens.

The Zeros were four kids hailing from Chula Vista, the second largest city in San Diego, California. Though Chicanos, some nicknamed them the “Mexican” Ramones. Their first single released in 1977 featured two songs, Wimp and Don’t Push Me Around. The later, with its snotty attitude, three chord minimalism, and defiant title, is a classic punk work. Hindsight allows us to see The Zeros as an extremely influential advance guard for a new music.

The concert also included Middle Class, a group of four young white lads from Orange County, California. Their debut EP, Out of Vogue, was released in 1978, just in time to bludgeon the punks at Baces Hall.

The lyrics to the song Out of Vogue encapsulated punk’s contempt for the wider society, “We don’t need your magazines, we don’t need your fashion shows, we don’t need your TV, we don’t want to know… Get us out of Vogue!”

At the concert the Committee to Defend the Houston Rebellion attempted to present a political slide show, but anarchistic punks kept standing in front of the slide projector to block the images. When the organizers tried to present Maoist style guerrilla theater on stage between the acts, they were met by the jeers and catcalls of the nihilistic spiky rabble. All three bands played typically searing sets, with the hoi polloi diving off the stage, bouncing off the walls, and in general kicking up their heels in wild punk abandon.

So there you have it. Baces Hall was torn down long ago and standing in its place today is another one of L.A.’s hideous commercial retail plazas, replete with a hipster juice bar. Punk is as dead as a doornail and there is little opposition to the mindless, dumbed-down, commercial pap that passes for culture in L.A. and beyond. Worst of all, police departments all across the U.S. have been militarized with billions of dollars worth of military equipment from the battlefields of Iraq and Afghanistan; police now have heavily armored, bomb resistant, MRAP fighting vehicles.

As the Clash once sang in their 1982 song, Know Your Rights, “You have the right to free speech, as long as you’re not dumb enough to actually try it.”

— // —

For more information on Joe Campos Torres and the Houston Uprising, watch the oral history series: The Case of José Campos Torres, produced by Ernesto Leon and available on YouTube: Part one, two, three, four, five, and six.