The Left Front: Defying Established Order

The Left Front: Radical Art in the “Red Decade,” 1929–1940, is a significant exhibit of American art created during the Great Depression years in the United States. Presented by the Grey Art Gallery at New York University in New York, the exhibit displays 100 artworks by forty notable artists of the period; including works by John Sloan, Raphael Soyer, Reginald Marsh, Mabel Dwight, and Louis Lozowick. Lynn Gumpert, the director of the Grey Art Gallery, said the following about the exhibit and its relevance to the present:

“In the wake of our recent ‘Great Recession,’ many artists today find themselves grappling with the same questions of art and activism raised by this exhibition. Indeed, The Left Front both opens a window onto a fascinating period in the history of American art and politics and brings to mind artistic responses to many of the very issues being confronted today, including alarming inequality in income and opportunity. In so doing, it asks what revolutionary art was during the turbulent 1930s, and what it can be in our own era.”

Ms. Gumpert’s concern for what revolutionary art “can be in our own era,” a period where art has become, not subversive, but subservient to wealth and power, is an urgent question for the arts community. Faced with deepening inequality, resurgent racism, ecological catastrophe, and the ever increasing drumbeat of war, artists should strive to offer critical visions of these systemic problems. By necessity this means turning from a self-absorbed, exclusively inward looking art, to one that is engaged with everyday people and the global community.

Herein lies the value of The Left Front exhibit. It provides an in-depth look at one aspect of Social Realism, a type of art that has almost been erased from historic memory in the U.S., a great irony given that the genre began in America with the painters of the so-called 1908 “Ashcan School.” After a slew of art movements since the close of the 2nd World War; abstraction, pop, conceptual, etc., it has became difficult to imagine that the Social Realist school was once a leading art form in the U.S. and around the world.

The school was varied and nuanced, and included American scene painters like John Steuart Curry and Thomas Hart Benton, as well as politicized African American artists like Aaron Douglas and Charles White. The Social Realist movement had three great centers, the U.S., Germany, and Mexico, each making their own unique contributions. Mexico gave the world Diego Rivera, David Alfaro Siqueiros, and José Clemente Orozco (Mexican creations are included in The Left Front exhibit). Germany gave us Käthe Kollwitz, Otto Dix, and George Grosz. Unfortunately Americans on the whole have largely forgotten about their homegrown Social Realist artists; you can attribute that in part to the Witch-hunts of McCarthyism.

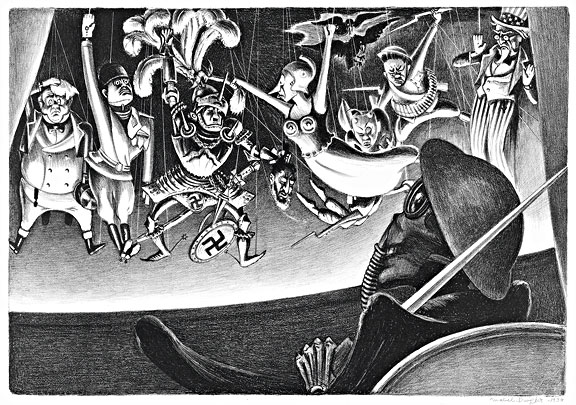

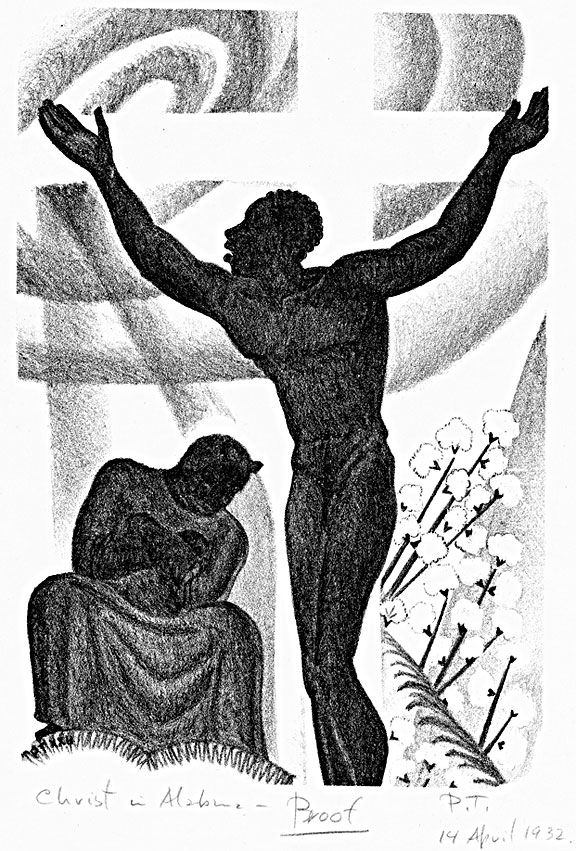

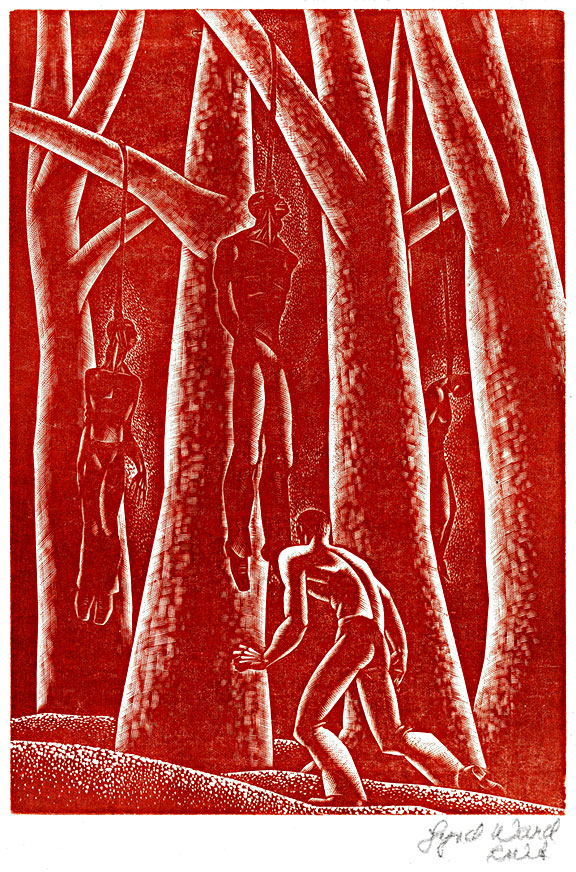

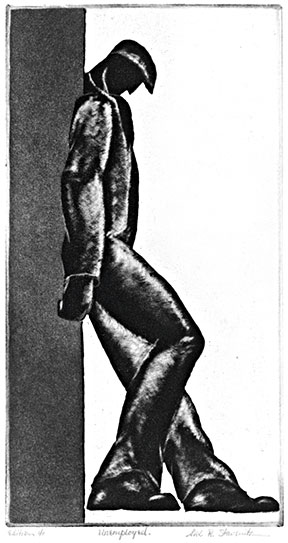

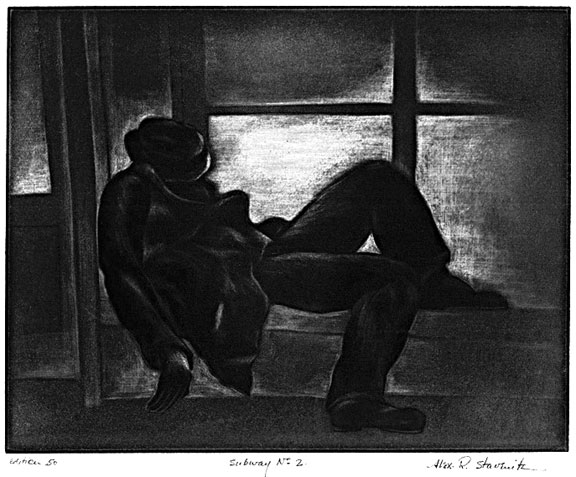

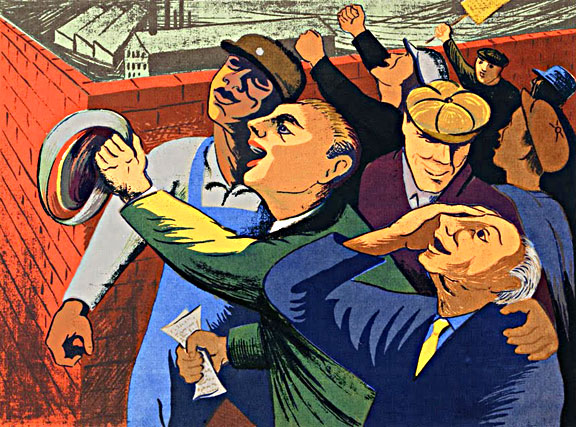

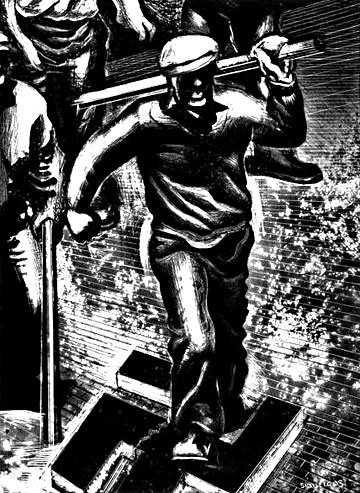

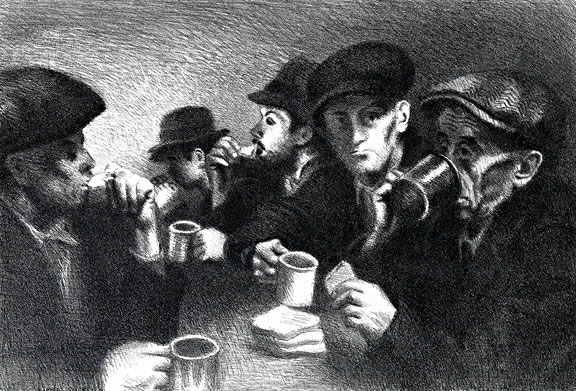

The Left Front exhibit presents works from the highly politicized branch of Social Realism, where artists used their work in an agitational manner to confront mass unemployment, class oppression, racism, lynchings, and the drive towards war that characterized the Great Depression years. The exhibit is comprised mostly of prints, although drawings, watercolors, paintings, and photos are also included. Inexpensive prints played a meaningful role for dissident artists during the Depression, they allowed low income people to bring art into their homes, and brought new aesthetics and politics to a wide audience.

Much of the art in The Left Front exhibit came from artists working with the John Reed Club, a U.S. national federation of left-leaning cultural workers and intellectuals named after American journalist and socialist activist John Reed.

Founded in 1929, the John Reed Club was eventually disbanded in 1935. While associated with the Communist Party U.S.A., members of the John Reed club were not necessarily Marxists or even CP members. I detail some of this in I wanted to tell stories, an Oct. 2006 article I wrote about the American painter Philip Guston.

The young Guston started his art career in Los Angeles as a realist painter before becoming an iconic figure in the New York School of severe abstract painting; thankfully Guston returned to realism, albeit a cartoonish version, in the late 1960s. But as a young man in L.A. Guston attended meetings of the John Reed Club held at the Italian Hall on L.A.’s famous Olvera Street.

Guston was one of those artists who worked with Siqueiros when the Mexican muralist came to L.A. in 1932. Guston joined Siqueiros’ Bloc of Mural Painters, artists who assisted Siqueiros in the painting of his famous América Tropical mural on Olvera Street. When the U.S. government unceremoniously deported Siqueiros in 1932, Guston continued working with the Bloc of Mural Painters. That same year the John Reed Club sponsored an exhibit of artworks created by Guston and the Bloc in opposition to racism and police brutality. Before the show’s opening the L.A.P.D. raided the John Reed Club gallery in Hollywood and destroyed the artworks, including Guston’s first public mural… the police shot the portable mural full of bullet holes.

The above is a perfect example of the political climate and repression that confronted oppositional artists during the 1930s, one should keep this in mind when thinking about The Left Front exhibition. Those who created prints depicting the terroristic lynching of Blacks won no favor from the art establishment; yet those artists defied the established order and pressed on with their wave-making art.

“Art as a social weapon” was the catchphrase of the John Reed Club. Before you laugh that off as a quaint and antiquated notion, I would suggest that art selected, curated, presented, and sold by elite art institutions has always broadly functioned as a social weapon. This was as true under the Ancien Régime of France’s Sun King as much as it is in the modern era.

It is my philosophy that a Jeff Koons is every bit as political an artist as those included in The Left Front exhibit. This matter is unequivocally nailed in the 1931 song, Which Side Are You On?, written during a miner’s strike by Florence Reese, the illustrious American folksong composer from Tennessee. Reese sang “Don’t scab for the bosses, don’t listen to their lies, poor folks ain’t got a chance unless they organize.” The song was tremendously popular with millions of down-and-out Americans in the 30s. The net worth of Jeff Koons is over $100 million, his kitsch baubles are popular with billionaires who prefer non-threatening art. Given the choice of standing with Koons or Reese, I will choose the poor folksinger every time.

One last word regarding Florence Reese and her famous workers’ rights song. On Oct. 4, 2014, during a St. Louis Symphony Orchestra performance of Johannes Brahms’ Requiem, paying members of the audience who also happened to be part of the Black Lives Matter movement, peacefully delayed the concert when they stood beside their seats while singing an altered version of Which Side Are You On?

In the ten year period covered by The Left Front exhibit, artists created works against racism, poverty, and the drive towards war, that is… the very same problems we have today. But what of the present? Who wins favor with the art establishment? Why are artists failing so miserably in addressing the world’s problems? Those in The Left Front show entrusted to us a people’s history and a record of resistance. They bequeathed to us images of transcendent beauty, unbreakable spirit, and deep humanism in the face of bottomless cruelty and inhumanity. Now it is our turn.