Prometheus: José Clemente Orozco

The first modern fresco mural to be painted in the U.S. by a Mexican artist was titled Prometheus, and it was painted in 1930 at Pomona College in Claremont, California by José Clemente Orozco.

I photographed the mural in late January 2014, and those photos are the focus of this web post: close-up details that show the artist’s hand and the technical bravura of Orozco’s fresco painting.

The College commissioned Orozco to create a mural for its newly constructed Frary Hall dining room, and the institution’s enthusiastic students helped to raise the necessary funds for the mural’s creation. The mural would occupy a twenty by twenty-eight foot wall behind a low stage located at the head of the hall, an architectural space encompassed by a ceiling high white plaster arch.

Orozco choose Prometheus as the subject of his fresco mural. One of the immortal Titans from the ancient Greek pantheon of gods and goddesses, Prometheus was said to have created man from clay, and then enraged the gods by giving mortals the gift of fire, enabling enlightenment, and progress. The Greeks of old considered Prometheus, not just a God of fire, but the bringer of the arts, sciences, and civilization. There is little wonder why Orozco the angry visionary decided to paint a mural of the Greek deity in an American liberal arts college. Cloaked in mythology, the work metaphorically addressed the state of the world, a subject never far from the artist’s mind.

The colossal figure of Prometheus (seen directly below) completely dominates the mural. As the Titan steals fire from heaven, earthly mortals surround him, jostling and writhing in various states of upheaval, bewilderment, and confrontation. From a distance one cannot see what Prometheus is reaching for because the arch obscures the ceiling and side panels of the mural. Stepping up to the lip of the stage it becomes apparent that the Titan is pulling fire down from the sky, the artist depicts this ingeniously.

The giant’s hands meld with flames in cubist abstraction, and the glow from the blaze illuminates the gargantuan form of the deity. Directly above this scene – though not shown in my photo – the ceiling is painted as the cobalt blue dome of heaven; a geometric abstraction painted in red hues represents God as a great mystery.

The illustration below shows a set of figures located to the lower right of the central figure of Prometheus. The cluster of men is part of a greater tableau that depicts masses of people in great anguish and turmoil.

The man with his arm raised seems to be reeling backwards, the man above him lurching forward belligerently; both are fine examples of how Orozco handled the human form. The figures are painted in near expressionist frenzy, a jumble of impasto brush strokes, watercolor-like washes, and incised lines scoured directly into the fresco’s wet lime plaster. There are an abundance of heavy black lines, but they do not delineate the figures, rather, they are heavily over-painted in a palette of volcanic earth tones – ochre, burnt sienna and umber, cadmium red. The colors, not line, define form.

Directly below is a set of figures located to the lower left of Prometheus. The faces belong to rough and primitive men. One of them lifts his eyes to gaze upon the mighty Titan, but the trio remains uncomprehending.

Orozco’s technique in the above is pure expressionism; the coarse faces are bluntly composed of forceful brushstrokes in black, along with smeared tones and thin washes of grey.

The grouping of women’s faces shown directly below are found in a crowd scene located at lower right of Prometheus. Entirely composed from thin washes of burnt sienna, the women could have been drawn by the great French political and social satirist, Honoré Daumier (1808-1879).

In the above, Orozco captured a range of emotions, from resigned indifference to hysteria. Unlike the fresco paintings of Diego Rivera, where the original outlines of a drawing can be detected beneath the washes of water-based paint, there is little evidence of Orozco using a detailed “cartoon” or drawing in charcoal to guide his application of pigments. Though he did use preparatory sketches in the production of his Prometheus mural, it largely has a free-hand, spontaneous quality to it. He painted broadly with washes, then adeptly used pointed brushes to add final linear details.

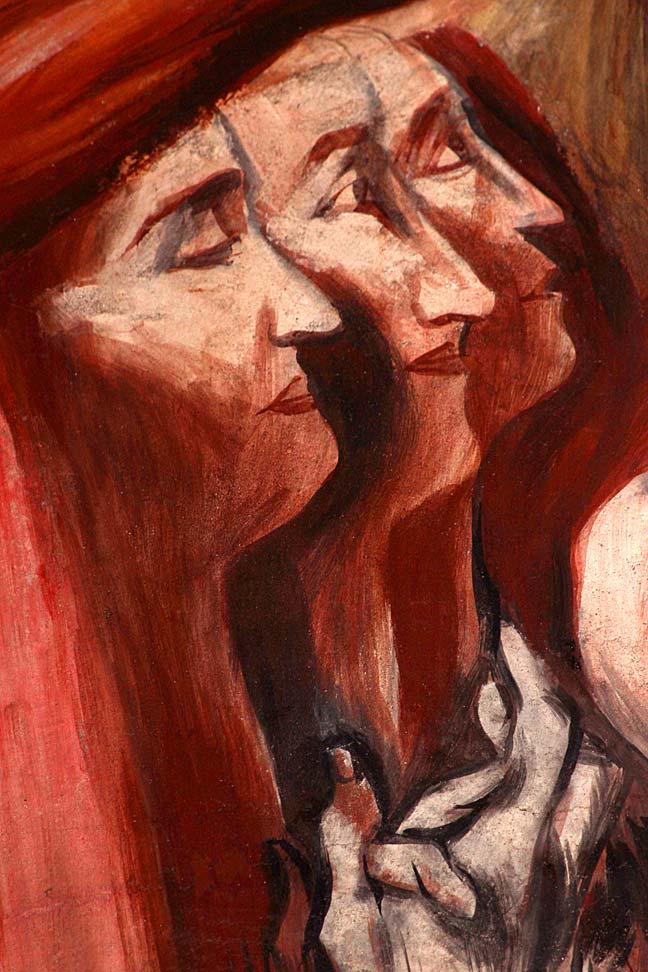

The trio of women shown above are found to the left of Prometheus. Beautifully painted in thin washes of red and black, they are the only mortals in the mural to appear benevolent and capable of lofty thoughts. Their hands clasped as if in prayer, they look skyward, ready for the fire that will grace humans with enlightenment. Again, the artist eschewed line in favor of using color to define form; the three women were painted quickly and seemingly without effort.

In the lower left of the mural, the figures shown below embrace. Surrounded by upheaval they await their fate in an uncertain world. Painted in a limited palette of earth tones, Orozco created the muscular back with broad brushstrokes, allowing color to modulate form. The light on the shoulder and arm was created by letting the white plaster ground show through the thinnest of washes.

Below is a stunning group of men’s faces that are located to the right of the central figure of Prometheus. They are part of a fraternity, and they march for some unknown cause. But the men are exhausted, and with their eyes closed their expressions suggest a certain fatalism, an acceptance of an unpleasant inevitability.

The above portraits bear a remarkable similarity – both compositionally and politically – to an earlier work by the magnificent German artist, Käthe Kollwitz (1867-1945). To protest the horror of war, Kollwitz created the 1921 woodcut, Die Freiwilligen (The Volunteers). She portrayed young German men volunteering to fight for the German Empire, being led to the battlefield by Death – who plays a military marching drum. In 1930 Orozco watched in dismay as young men once again readied themselves for sacrifice on the fields of war. As fascism was rising across Europe, Orozco’s mural was not simply the recounting of an ancient mythology, it was an expression of hope that the fire of Prometheus would bring enlightenment to us mortals before it was too late.

The detail of Orozco’s mural show below contains the same group of men written about in the above. It is however worth displaying a wider view of the scene for the brilliant compositional device the artist used showing the horizon line where fire from the sky met the earth. Note the downtrodden masses, ashen grey and heads bowed, who march with what appear to be black banners of political protest and struggle.

Orozco was sympathetic to revolution, but he also cautioned against revolutionary zeal going astray; the warning being that the oppressed would become the new oppressors. Orozco tempered the perception of insurrection with a visual trick; the banners held aloft in the above, are not political standards at all, but scorching fiery rays striking the earth as Prometheus steals fire from the heavens.

A tighter view of the same scene is found below; the detail of the crowd reveals a turncoat in their midst. The face of the backstabber is not shown in the photo, but at bottom right you can see his hand clutching a knife to stab the nearest blameless person. Orozco used this metaphorical device to rebuke the confusion and lack of unity found among suffering humanity.

There is of course much more to the Prometheus mural, but to show it all in detail on this web log would be too difficult. Instead, I invite everyone who finds themselves near Southern California to pay a visit to Pomona College to see the work up close in all of its grandeur. During the academic year Frary Hall is open everyday of the week, but only at certain times. Be sure to check their hours of operation if you plan a visit.