Diego Rivera: Pan American Unity

In 1940 Diego Rivera painted the huge fresco mural Pan American Unity for the Golden Gate International Exposition, which was held in 1939 and 1940 on California’s Treasure Island in the San Francisco Bay. Tens of thousands of visitors and tourists attended the exposition, which included the special showcase, Art in Action. People visiting the showcase could watch artists, such as Rivera – creating murals, lithographs, mosaics, sculptures, and other types of artworks.

Unbelievably, Rivera’s mural was disassembled at the closing of the fair and put in storage for twenty-one years. It would not be until 1961 that the mural was finally given a home in the then newly built theater of performing arts at City College of San Francisco – renamed The Diego Rivera Theater.

I took the following photographs of Rivera’s Pan American Unity during a 2011 trip I made to San Francisco. The presentation of these photos is another installment in a series of posts that document the murals created in the San Francisco Bay Area during the 1930s and 1940s. My intention is to provide high-quality, close-up photographic images of such murals; I especially want to give an artist’s view of the fresco murals, showing the painterly details usually missed in other online photographs.

My presentation focuses on details found in the section of the mural that is titled, Elements from Past and Present, seen below in a cropped overview. Compositionally, the upper portion of the mural segment portrays the “present” of San Francisco as it appeared in 1940 (that portion of the mural is not shown here). The lower portion of the mural that I put on view here, depicts political leaders and artisans from the yesteryears of the Americas.

Rivera inserted a portrait of himself into the tableau. Dressed in blue and with his back to the viewer, he depicted himself engaged in the act of painting. Surrounded by indigenous artisans, makers of sculpture, folk art, woven basketry, and ceramics, he portrayed himself as a descendant of humble craftspersons. To his right stand several revolutionaries from the turbulent history of the Americas. Commenting that art and culture are inseparable from politics, he pictured himself painting the “Tree of Liberty” that weds him to the revolutionary patriots of the Americas.

To Rivera’s immediate right stands Simón Bolívar (1783-1830), known as “The Liberator” for uniting the people of Venezuela (his birthplace), Columbia, Panama, Ecuador, Peru, and Bolivia, and leading them to independence against the Spanish Empire. Next to Bolivar stands Miguel Hidalgo y Costilla (1753-1811), the Mexican Roman Catholic priest who on September 16, 1810, rang the bells of his church in the small town of Dolores that declared the beginning of the revolution against the Spanish Empire. Hidalgo was eventually captured and executed by Spanish colonial authorities, but today his Grito de Dolores (Cry of Dolores) is celebrated every Sept. 16th as the beginning of Mexico’s successful War of Independence against Spain.

To the right of Hidalgo stands fellow Mexican revolutionary and Roman Catholic priest, José María Morelos y Pavón (1765-1815). Morelos assumed the leadership of the War of Independence after Hidalgo was executed by the Spanish, and was himself captured and executed by the Spanish on December 22, 1815. For the revolutionaries, victory was certain, and on the 21st of September, 1821, the Independentistas finally won their country’s liberation from Spain.

Following this pantheon of Latin American heroes, Rivera painted the portraits of George Washington (1732-1799), Thomas Jefferson (1743-1826), and Abraham Lincoln (1809-1865). Rivera paid homage to these U.S. patriots as world-historical figures that helped to advance the liberation of humanity. Washington and Jefferson of course were leaders of the world’s first anti-colonial revolution, a fact not lost on the anti-Imperialist Rivera. He painted Jefferson unfurling a parchment scroll upon which were written his famous words written in a 1787 letter to fellow patriot William Stephens Smith:

“What country ever existed a century and a half without a rebellion? And what country can preserve it’s liberties if their rulers are not warned from time to time that their people preserve the spirit of resistance? Let them take arms. The remedy is to set them right as to facts, pardon and pacify them. What signify a few lives lost in a century or two? The tree of liberty must be refreshed from time to time with the blood of patriots and tyrants. It is it’s natural manure.”

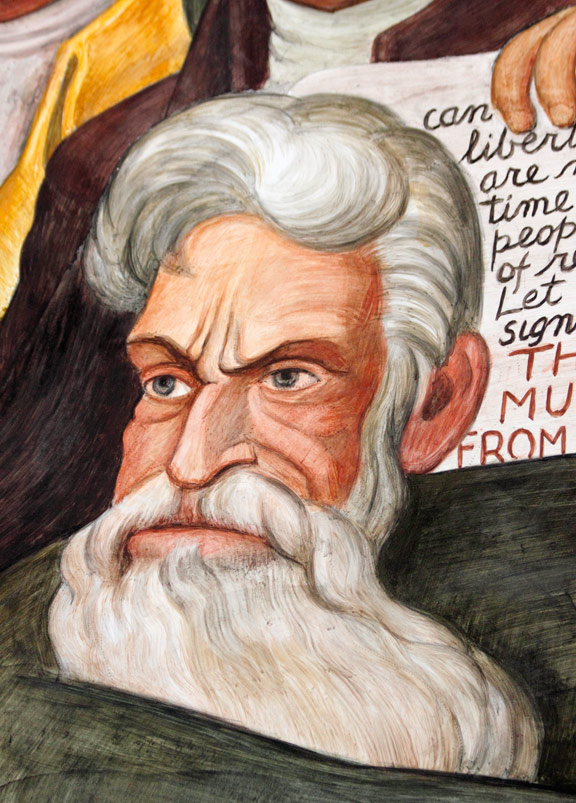

With Jefferson’s “Tree of Liberty” quote as the backdrop, Rivera painted a portrait of radical abolitionist John Brown, who on October 16, 1859, led 18 followers on an armed raid against the federal armory at Harper’s Ferry in West Virginia. Believing that armed struggle was the only recourse left to abolish slavery, Brown seized Harper’s Ferry in the hope the raid would spark a massive slave rebellion that would topple the slave system and purge slavery from the land. The raid failed when on October 18, U.S. Marines stormed the armory, captured Brown and killed or apprehended his men. A trial found Brown guilty of “treason against the Commonwealth of Virginia” and he was hanged on December 2, 1859. It could be said that Brown’s daring raid on Harper’s Ferry was the opening salvo of the U.S. Civil War.

Rivera painted a crowd of people paying rapt attention to the oratory of the fiery abolitionist, John Brown. These two faces in the crowd are situated beneath the portrait of Simón Bolívar. Painted in profile, the couple received only the barest attention from Rivera, they were painted with extreme rapidity – yet, their faces are complete. The portraits reveal much about the process of fresco painting. They are painted in the thinnest of washes, the overall effect looking much like something drawn with a magic marker. If you look closely at the eyebrows, noses, and hairlines of both figures, you will see a number of tiny dots, those are the original outlines of the drawing before it was painted.

Fresco entails the use of water-based pigments that are painted directly onto wet plaster. To begin painting an artist first places a “cartoon” on the fresh plaster. The cartoon is a preparatory drawing on paper, the drawn lines of which are perforated with pin prick holes. The artist then “pounces” the cartoon, that is, a small cloth bag filled with powdered pigment is lightly tapped all along the perforated drawing – transferring the sketch to the wet plaster. At that point the actual painting may start. Absorbed by the lime plaster as it dries, water-based pigments become fixed to the plaster. This photo shows the original pounced pigment outlines on the faces of Rivera’s subjects.

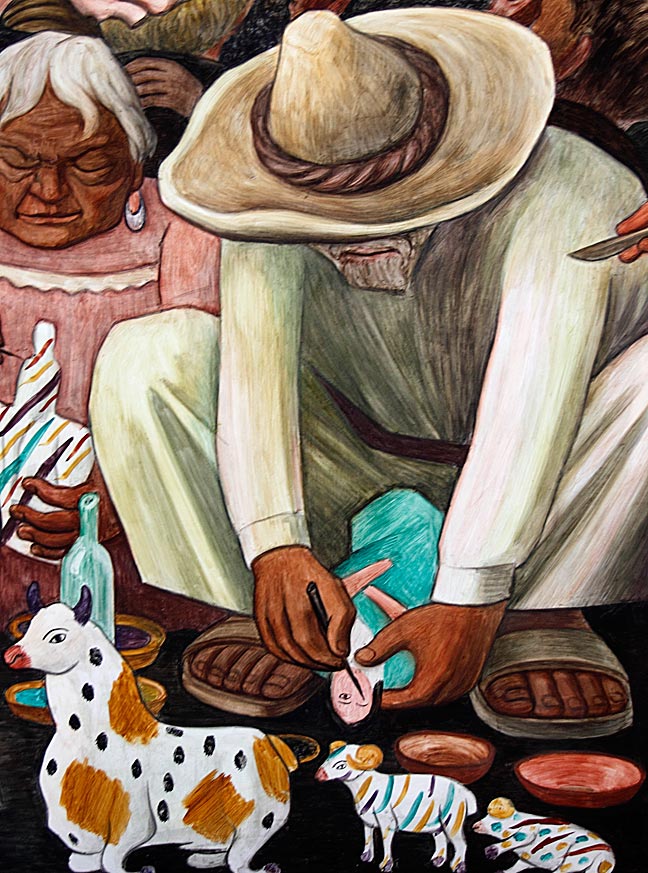

This large detail from the mural could stand alone as a successful easel painting. Its subject is an elderly campesino couple at work creating ceramic folk art; the old man uses a small brush to paint a face upon a clay female figurine. In Mexico the production of earthenware utensils and painted sculptural objects can be traced back to 2300 B.C., and over the centuries the art passed through the hands of Olmec, Zapotec, Maya, Aztec, and many other indigenous cultures. The Spanish invaders brought their own influences; the potter’s wheel, enclosed kilns, new pigments and lead glazes. As the indigenous and Spanish merged, new traditions evolved that transformed Mexico’s already unique earthenware art into some of the world’s most sophisticated ceramics; no doubt Rivera had this history in mind when he painted this scene.

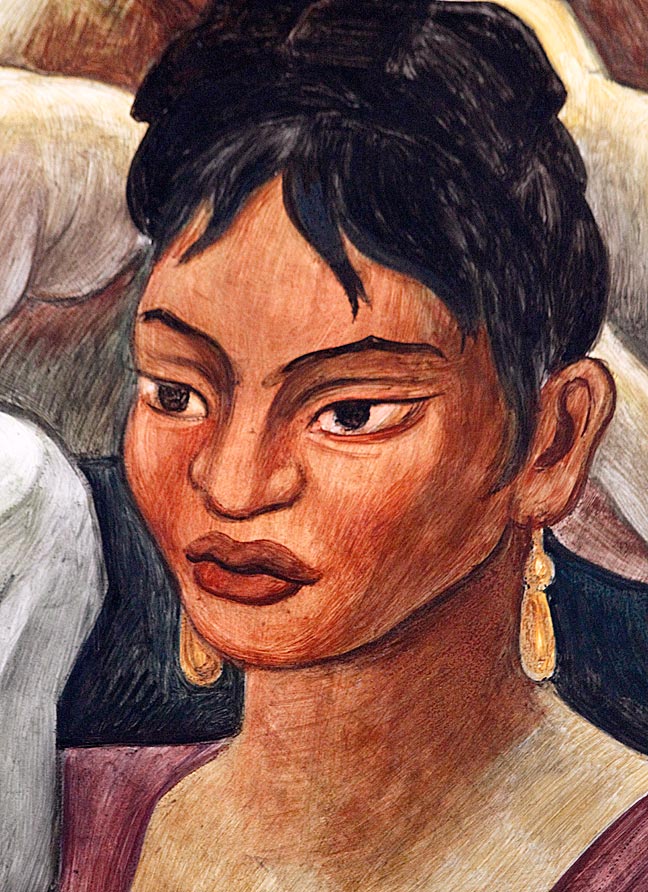

In the lower right corner of his composition, Rivera painted this beautiful portrait of a woman of Tehuantepec as she shapes a wet clay statue with a pottery knife. Though Rivera used a minimalist style in his fresco murals to conform with the quick drying quality of the medium, his representation of the Tehuana is highly finished and lovingly painted. Note how he used the sharp end of a paintbrush to scratch highlights into the women’s chin and jaw line.

Rivera interspersed images of war throughout his mural to make plain that conflict sometimes cannot be avoided; Latin America won its independence from colonial Spain using revolutionary violence; Washington and Jefferson helped to win America’s independence from Britain by means of war; President Lincoln preserved the union and eventually ended chattel slavery by way of warfare. Rivera was stating that selecting peace was not always the same as choosing liberty.

At the time of creating his painting in 1940, World War II (1939-1945) was already in full swing; WWII actually began in 1936 when General Francisco Franco and his fascist army attempted to overthrow the Spanish Republic. In 1936 Rivera and Frida Kahlo worked to raise funds in support of the beleaguered Spanish Republicans, so there is no doubt Rivera viewed the Spanish Civil War as the beginning of a world-wide conflagration. While the Elements from Past and Present section of Rivera’s mural did not deal specifically with the issue of WWII, he did address it unambiguously in panel 4 of his mural (images from which I will post at a later date).

In the Elements from Past and Present mural panel, a small passage in the upper right-hand corner of the composition dealt with the looming tragedy of the Second World War. The scene has no particular focus, but it acts as a reminder of realities masked by calm panoramas. One must think of the tens of thousands of people who stood before Rivera’s mural in 1940 during the Golden Gate International Exposition, and what they must have thought about what Rivera portrayed; world war was the furthest thing from the minds of a good number of Americans. The U.S. would not enter WWII until December 8, 1941 (the day after Japan bombed Pearl Harbor).

In this section of the mural Rivera painted fire licking the turret of the cannons pointed at the viewer, bayonets raised in anger, a woman carrying a dead child with shrapnel wounds in its head, a fist punching the air. It could have been a depiction of any number of events that occurred in the Americas over many decades – revolutions and counter-revolutions. But Rivera also included in the scene the fasces symbol of ancient Rome, used by Benito Mussolini’s regime as the symbol of Italian fascism. Rivera was clearly warning viewers about European fascism, which he correctly believed could only be toppled by force of arms.

El Maestro at work. Rivera depicted himself in a bright cerulean blue work shirt, holding a brush as he paints. This detail allows one to see the technique employed by Rivera in painting his fresco. The painting of the shirt was created in layers, first an underpainting wash of diluted blue, over which the darker and more vibrant cerulean was painted. The brushwork is rapid and its touch light; the artist does not linger for very long on any aspect of the work.

Along with his fellow Mexican Muralists, Rivera was an advocate of muralism as a “people’s art”. Yes, his murals were “public works of art,” but not in the sense of today’s superficial public works. His interest was not in richly festooning city walls, or painting over the cracks of a flawed society – he had deep social concerns, and believed art could play a key role in creating a better world. As he once put it: “It is said that revolution doesn’t need art, but that art needs revolution – that is not true. Revolution needs a revolutionary art.” (Amazingly enough, that quote, along with a self-portrait of Rivera, appears on the 500 Pesos Bill issued by the Bank of Mexico in 2010).

A prime example of that revolutionary art can be seen at the City College of San Francisco. In Rivera’s vision of Pan-American unity, the artist gifted us with powerful depictions of U.S. historical events and figures. It would be an outrageous scandal of the highest order if Rivera’s mural were to be disassembled and put in storage once again.

— // —

Sadly, Diego’s mural was disassembled and put in storage once again. It was disassembled and moved from its original location at City College of San Francisco (CCSF), to the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art (SFMOMA). There it was renovated and restored before being displayed from June 2021 to Jan. 2024. The mural was again disassembled and sent back to CCSF and put in storage.

Supposedly the CCSF is planning to build a new Performing Arts Center, where the mural will be installed. As of this writing (11-24-2025) construction has not begun. Supposedly the new 77,000-square-foot facility will be completed 32 months from when work begins. As of this date construction costs are estimated to be $190 million, but we’re talking about California, so costs will no doubt rise. As for seeing Diego’s mural again…don’t hold your breath.

POSTS IN THIS CONTINUING SERIES:

Coit Tower Crisis

Arnautoff & the Chapel at the Presidio

Diego Rivera: The Making of a Fresco