Arnautoff & the Chapel at the Presidio

Nestled in the middle of the Presidio of San Francisco, California, is a small Spanish Colonial style Chapel surrounded by a grove of Eucalyptus trees.

The Chapel at the Presidio houses an impressive but little known Great Depression era mural by Victor Arnautoff (1896-1979). I visited and photographed the mural in late 2011, and will here share my observations.

Sitting atop a hill, the Chapel affords a fine view of the San Francisco Bay area. Within the grounds of the Presidio and not far from the Chapel you will find the San Francisco National Cemetery, where 30,000 American war dead from the late 1800s to the present are interned.

In 1931 the U.S. Congress gave the U.S. Army $40,000 to build the Chapel; it was constructed in Spanish Colonial Revival style architecture, and with its heavily stuccoed walls, stained glass windows and bell tower, it was – and still is – quite a sight to behold.

In Feb. of 2009 I wrote a review in praise of Arnautoff, whose works were on display at an exhibit of California Modernist Paintings at the Spencer Jon Helfen gallery in Beverly Hills, California. The article examined the life story of the artist in some detail. Despite my high opinion of Arnautoff, it was the most I had ever written about the artist – until now.

The Russian born Victor Arnautoff looms large in my pantheon of great artists, though most other Americans long ago forgot his name. As a young man he was a Cavalry Officer in the Tsarist Imperial Army, and so fled Russia sometime after the 1917 Bolshevik Revolution. He traveled to China and Mexico before finally coming to the U.S. and settling down in the city of San Francisco in 1925. Arnautoff eventually became allied to the communist Mexican Muralist Diego Rivera, both aesthetically and politically, and from 1929 to 1931 Arnautoff lived in Mexico as a student and assistant of Rivera.

When Rivera left Mexico City to visit San Francisco in 1930-31, he left the painting of his National Palace frescos depicting Mexico’s history in Arnautoff’s capable hands. Arnautoff joined Rivera in San Francisco in 1931 to help paint The Making of a Fresco Showing the Building of a City at the San Francisco Art Institute. Arnautoff is best remembered for City Life, his 1934 mural in San Francisco’s Coit Tower, that, and his being the technical director of the Coit Tower mural project. Arnautoff had come full circle from his early years as a Tsarist officer to his participating in the left-wing artistic circles of the U.S.

After completing work on the stunning murals at Coit Tower in 1934, Arnautoff was given a commission in December of that year to create a fresco mural on the east wall of the Chapel at the Presidio of San Francisco, then one of the most important U.S. military installations in all of the United States. The commission was for a mural that depicted the peacetime activities of the U.S. Army, but the mural would also include the history of the land and its people upon which the Presidio was established.

Measuring 13 x 34 feet, Arnautoff’s mural was originally located on the outside east wall of the Chapel, greeting those who entered from the side entrance. With time it was decided to enclose the area where the mural stood, creating a hall between the side entry and the Chapel wall where the fresco mural is painted. This narrow vestibule protects the fresco mural and serves as an information and greeting area for those tourists who visit the Chapel. However, the limited width of the antechamber prevents one from standing back far enough to view the mural in its entirety, for the same reason it is extremely difficult to photograph the complete mural. Given these limitations, I was only able to photograph specific details of Arnautoff’s splendid painting.

The mural was sponsored by the officers of the 30th U.S. Infantry, however, it was funded by California’s State Emergency Relief Administration (SERA); a state agency financed by President Roosevelt’s Federal Emergency Relief Administration (FERA). Arnautoff’s Coit Tower mural had been funded by Roosevelt’s Public Works of Art Project (PWAP). These and other “New Deal” programs provided work to 40,000 artists, helping to ease the ravages of the Great Depression. Arnautoff pulled together a team of artists to paint the mural; A plaque painted into the lower left corner of the mural includes Arnautoff’s name as well as those of his assistants; Suzanne Scheuer, B. Cunningham, Edward Terada, Richard Ayer, M. Hardy, P. Hall, P. Vinson, G. Serrano, M. Cohen, P. Zoloth, T. Mead, and W. Mannex. In 1935 the crew completed the mural in 42 days.

The Spanish first erected their San Francisco Presidio in 1776, when Spain ruled over Nueva España (New Spain) – colonial holdings that contained most of what is now the Southwest of the U.S., all of Mexico, Central America, the Caribbean, and large areas of South America. When Mexico won its war of independence against Spain in 1821, the Presidio passed into Mexican hands. Territorial expansion by the U.S. led to its 1846 invasion of Mexico. After the U.S. Army seized Mexico City, the Mexican government had no choice but to sign the “Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo”, which ended the war but ceded to the U.S. lands that included California, Nevada, Utah, much of Arizona, half of New Mexico, and parts of Colorado and Wyoming.

As a political radical Arnautoff was certainly aware of the Presidio’s long history as delineated in the above. He had come under enormous criticism from the U.S. right-wing for his directorship of the 1934 Coit Tower mural project; San Francisco’s right excoriated the murals as “communist propaganda”, and the press demanded the murals be altered or obliterated. Consequently Arnautoff seemingly avoided a confrontational examination of the Presidio, this was after all a mural commissioned by the U.S. military to be housed on a major U.S. military installation. Still, Arnautoff did manage to include certain understated narratives in his fresco that were quite bold given the political circumstances in the U.S. at the time.

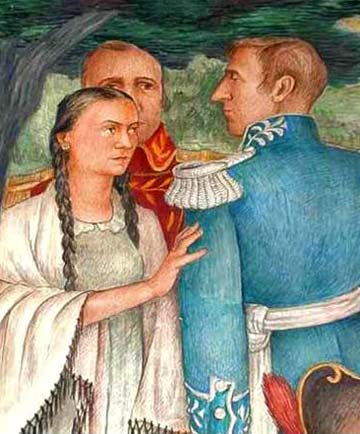

Arnautoff painted an interesting trio in the upper left portion of his mural; Maria de la Concepción Marcela Argüello, her father Don José Darío Argüello (pictured dressed in a red uniform and standing behind his daughter in the mural), and the Russian chamberlain to Tsar Alexander I, Nikolai Petrovich Rezanov – all historic figures from late 1700s San Francisco, California.

When the story of Concepción Argüello and Nikolai Rezanov is remembered at all, it us usually framed as “California’s oldest and saddest romance“. Beneath the supposed ardent love affair was the machinery of imperialism and colonial conquest, and though I have no proof, I am convinced that was the actual narrative Arnautoff meant to subtly provide viewers of his mural.

On Sept. 4, 1781, Don José Darío Argüello founded El Pueblo de Nuestra Señora la Reina de los Ángeles (the Town of Our Lady Queen of the Angels), in the Las Californias sector of New Spain; The Pueblo de los Ángeles would of course become Los Angeles, the megalopolis we know today and coincidentally the city of my birth. In 1787 Argüello was appointed Comandante of the Presidio of San Francisco, and his daughter, Concepción Argüello, was born in the Presidio in 1791. Rezanov was a high-level official in the Tsarist regime and a supporter of Russian imperialism; he strove to transform Russia into a dominant power in the Pacific by establishing commercial and military outposts from Alaska to California.

As part of his imperial mission the 42-year-old Rezanov sailed to San Francisco in 1806, where he was feted by Don Argüello at the Presidio. It was at the Spanish military outpost that Rezanov met the 15-year-old Concepción Argüello, and according to the myth, the two supposedly fell in love and became engaged that same year. Since the laws of Spain prohibited its colonies from trading with foreign powers, maybe Rezanov’s motivation in wanting to marry Concepción had more to do with profitable colonial ambitions than actual romance.

At any rate, the Spanish Catholic priests refused to bless Concepción’s marriage to Rezanov, who was Russian Orthodox. Six weeks after arriving at the Presidio, Rezanov began a return trip to Russia, he intended to send entreaties to the King of Spain for royal consent to marry Concepción Argüello. Perhaps he considered it even more important to appeal for a trade agreement between Spain and Tsarist Russia. Whatever the case, Rezanov died of fever in 1807 before reaching home, and the young Concepción “renounced the world” to become a nun. She died in 1857 as Sister Mary Dominica Argüello of the Dominican order in Monterey, California.

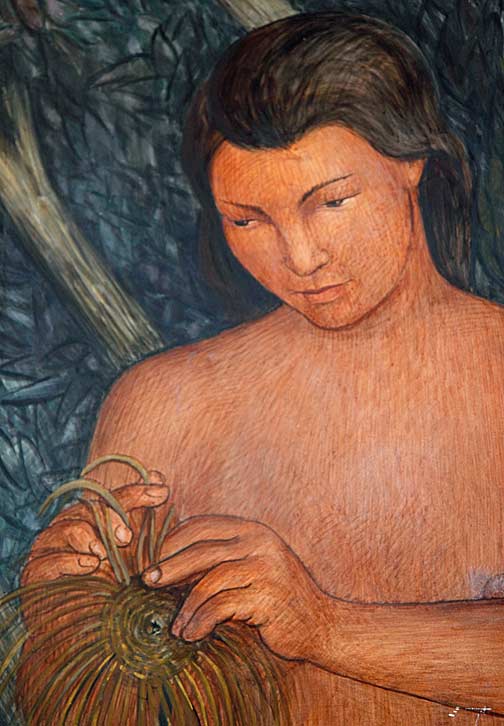

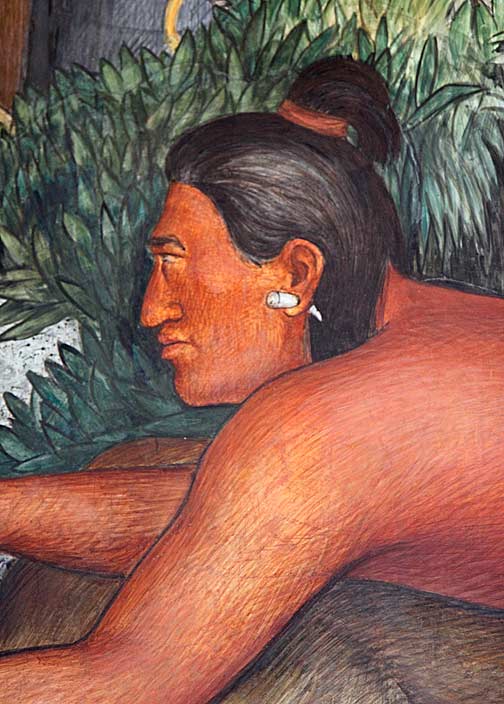

As a sidebar to the 1806 Rezanov-Argüello story, in 1816 another Russian sailing ship named the Rurik landed at the Presidio. Among its 30 man crew was Louis Choris (1795-1828), a talented 21-year-old Russian/Ukrainian artist. Choris was the expedition’s official artist and during the month the Rurik was anchored in San Francisco Bay, Choris created the earliest depictions of the region’s indigenous Ohlone tribe. He made stunning watercolor paintings portraying individuals and groups of people going about their daily routines.

After his Rurik journey Choris traveled to Paris in 1819 where he produced portfolios of hand-colored lithographs that illustrated his encounters with the Ohlone nation. In terms of ethnographic study, Choris’ artworks provide in-depth and accurate observations of a way of life now vanished.

The Ohlone lived in over fifty different villages and tribal groups throughout the San Francisco bay area and beyond to the shores of Monterey Bay and the Salinas Valley. They were hunters and gatherers that lived off the bounty of the land. They believed an enormous flood had once engulfed the earth, leaving only two small islands to be inhabited by only three survivors… Coyote, Eagle, and Hummingbird, who together created the human race. The Ohlone said that Hummingbird brought fire to the people.

Tule reed was used to make Ohlone homes, clothes, baskets, mats, and boats. The people fished in salt and fresh water catching all types of fish, shellfish, and crustaceans. They gathered endless varieties of nuts, seeds, bulbs, tubers, acorns, mushrooms, greens, and berries. Rabbits, deer, antelope, and elk were hunted, as well as a sizeable array of birds. Many other creatures large and small were a part of the Ohlone diet, grasshoppers, grubs, lizards, snakes, squirrels, even an occasional beached whale.

I consider the principal focus of Arnautoff’s mural to be his depiction of the Ohlone tribe. Compositionally the mural’s central motif is a religious one that depicts a monument to St. Francis. Franciscan Friars not only founded and named the first Catholic Church in San Francisco in 1776, they named the mission church and the entire region after their patron saint, Saint Francis of Assisi. Be that as it may, the first people to inhabit “San Francisco” were not Spanish Catholics but the shamanistic Ohlone, and they settled the region some 5,000 years ago.

Given the short shrift indigenous people have received in both American history and cultural representation, Arnautoff’s focus on the Ohlone was a remarkably subversive gesture for 1935. His well researched portrayal of the indigenous population was no doubt facilitated by the drawings, paintings, and lithographs of Louis Choris.

I would like to re-emphasize to the reader the impact Diego Rivera had upon Arnatauff. As with most other Mexican artists of his time, Rivera sought to create a national art that was independent from Europe. This was accomplished in large part by establishing Mexican art on the foundational bedrock of aesthetics developed by the prehispanic indigenous Olmec, Maya, and Aztec civilizations. When viewing Rivera’s portraits of everyday Mexicanos, it is not the classical beauty of Europe that one sees reflected, but the grandeur of indigenous Palenque and Tenochtitlán. I am sure Arnautoff valued the reasons behind Rivera’s glorification of the Western Hemisphere’s first inhabitants, and so included the Ohlone in his Presidio mural on the same grounds.

If the left-side of Arnautoff’s mural portrays the early history of the Presidio, then the right-side of the fresco depicts the U.S. Army carrying out projects at the Presidio during the 20th century. The two scenes I will focus on from that portion of the painting have to do with General John Joseph “Black Jack” Pershing, as well as the role the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers played in building the Panama Canal.

General Pershing had, let us say, an “interesting” career in the military. As a graduate of West Point in 1886 he was assigned to the 6th U.S. Cavalry, where he fought the Apache nation in the so-called “Apache Wars”; Pershing took part in military operations to force the Apache onto reservations and keep them there. In 1890 Pershing and the 6th Cavalry were sent to South Dakota to crush the Lakota Nation, then engaged in their last uprising that would culminate in the U.S. Army massacre of some 300 unarmed Lakota at Wounded Knee (Pershing was not directly involved). In 1892 Pershing became a first lieutenant assigned to the 10th Cavalry “Buffalo Soldier” regiment of African-Americans (earning the nickname, “Black Jack”). He fought in the Spanish-American War (1898) as a major with the 10th Cavalry in operations at San Juan Hill. As a Departmental Adjutant General, Pershing fought against the Moro uprising in the Philippines from 1899 to 1903.

In 1906 President Theodore Roosevelt promoted Pershing to Brigadier General, but it was President Woodrow Wilson, a “progressive”, that sent Pershing into Mexico in 1916 on a “punitive expedition” to kill or capture the Mexican revolutionary Francisco Pancho Villa. Commanding the U.S. Army 8th Brigade and a force of 11,000 soldiers, Pershing failed to crush Villa and his guerilla army, but the mission was not without its successes. The operation employed the 1st Aero Squadron of eight Curtiss JN-3 “Jenny” biplanes for aerial observation and intelligence gathering, the very first time the U.S. Army made use of airplanes in combat; the application of airpower foreshadowed the mechanized slaughter that would come but a year later. In April 1917, the U.S. entered World War I, and President Wilson promoted Pershing to General in charge of the American Expeditionary Force to Europe.

Arnautoff had to be aware of Pershing’s war record, and as a man of the left he must have viewed Black Jack unfavorably. Arnautoff and his circle of artists, being sympathetic to radical ideas, were alarmed by the rise of fascism in Europe and the growing threat of war. They were no doubt familiar with the speeches and writings of retired Major General Smedley Butler of the U.S. Marine Corps, who in 1935 was the most decorated Marine in U.S. history. He was also a spokesman for the American League Against War and Fascism, and had been engaged in a nationwide tour to deliver his speech “War is a Racket“. Butler addressed how oligarchs made soaring profits from the blood and suffering of soldiers. In 1935 he published a longer version of his speech as a small book, also titled War is a Racket. To get an idea of how widely distributed and influential Butler’s work was, Reader’s Digest condensed it as a book supplement.

In his mural Arnautoff did not directly portray General Pershing, in fact the artist could hardly have been said to paint Pershing’s portrait at all. What Arnautoff did was to paint a high-ranking military man with his back towards the viewer while commanding volunteers in putting out a raging fire; I think the artist was alluding to a terrible tragedy that struck ol’ Black Jack. Just prior to the “punitive expedition” in Mexico, Pershing received a blow he never recovered from. On August 27, 1915, while at the “Fort Bliss” military encampment near El Paso, Texas (the base from which Mexico would be invaded), Pershing received a telegram concerning his home at the Presidio in San Francisco. A fire had burned his multi-storied, wooden Victorian mansion to the ground. Worse still, the inferno had almost consumed his entire family – his beloved wife and three of his four children. One could take this panel as a portrait of a very powerful man laid low by forces beyond his control.

The final tableau in Arnautoff’s mural had to do with the role of the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers (USACE) in building the Panama Canal. The mural depicts the USACE construction the Gatun Lock Gate, one of three enormous lock systems that lift and lower water levels making navigation of the Panama Canal from the Atlantic to the Pacific ocean possible. Ironically, this segment of the painting reveals both the artist’s left-wing ideology as much as it does some apparent contradictions.

Panamanian separatists broke free of Columbia with U.S. military assistance in 1903 and immediate formal recognition of the Republic of Panama came from U.S. President Theodore Roosevelt that same year. The U.S. Secretary of State John Hay signed the so-called “Hay-Bunau Varilla Treaty” of 1903 with the French engineer and soldier Philippe-Jean Bunau-Varilla, giving control of the Panama Canal to the United States – even though not a single Panamanian signed the treaty. That detail alone would have been important to an anti-imperialist like Arnautoff, but how did he represent the history of the Panama Canal vis-à-vis its relationship to the U.S.?

The artist no doubt thought the U.S. was meddling in Panama, but refrained from criticizing U.S. policy, preferring instead to focus on men having achieved one of the world’s great engineering feats. Arnautoff’s mural glorifies what workers can achieve through the miracles of science and technology; given his benefactors, he could hardly have said more. Thematically, the Gatun Lock portion of Arnautoff’s mural is similar to Diego Rivera’s Allegory of California mural painted at the San Francisco Stock Exchange Tower in 1931.

While portraying agricultural richness, scientific innovation, and technological advancement, Rivera’s Allegory of California mural was not a celebration of capitalism, rather, it was a depiction of the working class, its capabilities and its future potential. These views were entirely in keeping with the pro-socialist sympathies of many artists at the time; one should be reminded that in 1934 the Soviet Union was considered a symbol of hope and progress by many, the crimes of Stalinism had yet to occur, and that the U.S. and the Soviets would soon become allies in the war against Fascism.

It is also interesting to note that the U.S. Army staff in the lower portion of the scene are examining plans to build the Golden Gate Bridge. Construction of the now world-famous suspension bridge began on January 5, 1933, just prior to Arnautoff and his assistants working on their Presidio mural. Arnautoff portrayed American engineer Joseph Strauss, the designer of the bridge, pointing at a model bridge while conferring with army officers.

Although the army did not play a direct role in the bridge’s physical construction, the U.S. Department of War was consulted since its Civil War era Fort Point apparently stood in the way of the bridge’s construction.

Construction of the Golden Gate Bridge would be completed by April of 1937, two years after the completion of Arnautoff’s mural.

I might add that historic Fort Point remained untouched during the bridge’s building; the fortress is a must see tourist destination in its own right, being one of the best preserved all brick U.S. military fortifications in the entire U.S.

The mural located at the Chapel at the Presidio is a little known painting by the underappreciated Victor Arnautoff. While relatively obscure, the work is a gem from the WPA era of American mural painting, in actuality it is a foundational stone of contemporary muralism. Considering the state of the art world and of society in general, it is no surprise Arnautoff’s mural is left unrecognized and uncelebrated. However, its aesthetics, brilliant execution, historical and political insights, and geographical setting make it a “must see” destination for anyone traveling to San Francisco.

POSTS IN THIS CONTINUING SERIES:

Coit Tower Crisis

Diego Rivera: The Making of a Fresco

Diego Rivera: Pan American Unity