Farewell Mr. Deitch

Jeffrey Deitch is throwing in the towel after serving as the director of the Museum of Contemporary Art, Los Angeles (MOCA) for three uneasy years out of his five-year contract. Details concerning his reign at and departure from MOCA abound, but you will not find the minutiae detailed here.

A large segment of L.A.’s art community did not trust Deitch from the very beginning, viewing him as an entrepreneur that wanted to transform MOCA into a celebrity theme park rather than a serious art institution. In June of 2012, MOCA’s curator Paul Schimmel was apparently fired by Deitch, though the circumstances remain unclear. After Mr. Schimmel’s firing, the four artists that sat on MOCA’s board of directors resigned.

Wanting to share my annoyance over Deitch’s style of directorship led me to write an essay in 2011 that remained unpublished – until today. I was pleased that Schimmel selected a work of mine to appear in his 2011 Under the Big Black Sun: California Art 1974-1981 exhibit at MOCA, but I continue to be critical of MOCA and its departing director. Though I never published my 2011 missing essay, I have decided to do so now as a sort of farewell to Mr. Deitch. That original essay is presented here for the first time:

— // —

You might say the premise of this article has its basis in a quote from Oscar Wilde, “Everything popular is wrong.”

In 2008 the Museum of Contemporary Art (MOCA) was in deep financial crisis and faced the danger of being shut down altogether. By 2009 the museum’s yearly attendance had dwindled to a mere 148,616 visitors, and its endowment fund, plundered to maintain museum operating costs, hit its lowest point since MOCA’s founding in 1980. Eli Broad (with a net worth of some $5.8 billion) bailed out the failing museum in Dec. of 2008 to the tune of $30 million dollars, adding it to his growing collection of L.A. cultural institutions he controls or influences.

Mr. Broad, the founding chairman and now life-time trustee of MOCA, was interviewed by the New York Times, where he said that in the wake of MOCA’s collapse and rescue the museum’s board sought a new director “who was, call it what you want, a game-changer, an impresario.” That flashy entrepreneur turned out to be Jeffrey Deitch, and he was appointed director of MOCA in 2010.

Up until Deitch’s entrenchment at MOCA, museum directors have generally come from the world of academia. Deitch is the first art dealer and commercial art gallery owner to be named director of a major non-profit museum, an appointment that signaled how museums will be run in our new gilded age. Before Deitch began his foray into the world of art he obtained a Master of Business Administration from Harvard and became Vice President of the international banking giant, Citibank. Moving from financial services, Deitch became an extremely successful and well-connected “art consultant,” servicing several high-end corporate collections. He then became a successful art dealer and established his for profit gallery, Deitch Projects, in 1996.

It is enough that many observers have compared Mr. Deitch to P.T. Barnum, that supreme American huckster known for exhibiting “human curiosities,” the marketing of hoaxes, the founding of Barnum & Bailey Circus, and for allegedly coining the phase “There’s a sucker born every minute.” A similar assessment of Deitch came from the senior art critic of Artnet.com, Charlie Finch, who wrote; “As with Cecil B. DeMille, the three words to describe Jeffrey Deitch are control, self-promotion and spectacle.”

Art in the Streets was curated by Jeffery Deitch and the exhibit ran at the Geffen Contemporary at the Museum of Contemporary Art (MOCA) of Los Angeles, from April 17, 2011 until August 8, 2011. According to the museum’s press release, the show was “the first major U.S. museum survey of graffiti and street art” that traced the development of the phenomenon from “the 1970s to the global movement it has become today.” Far from being a review that offers considered opinion on the strengths or weaknesses of street art, this article instead focuses on the mechanics of the MOCA show, a process that barely concealed a money mad art market seeking to commodify art from the street.

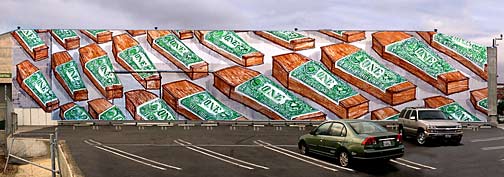

MOCA’s Art in the Streets exhibit received a lot of media attention, even months before the show opened its doors to the public. Jeffrey Deitch commissioned the Italian street artist named Blu to paint a mural on an outside wall of the Geffen Contemporary as part of the effort to generate publicity for the exhibit.

Known for his politically pointed images, Blu finished his contentious but awkward mural on Dec. 8, 2010. It depicted giant coffins wrapped in U.S. dollar bills, a caustic statement regarding the never ending wars in the Middle East and beyond that the U.S. is actively engaged in.

The very next day Deitch had the entire mural whitewashed, even though MOCA had received no complaints regarding the artwork. Deitch said the mural might have been offensive to some since it was located in the general vicinity of the Go For Broke Monument, a national memorial to the Japanese American soldiers who fought in World War II.

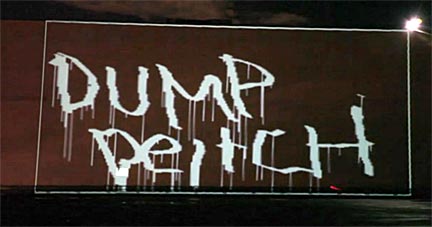

By whitewashing Blu’s antiwar mural, Mr. Deitch left himself open to denunciation. Alarmed over censorship, the L.A. art community’s concern was translated into action on the streets of downtown L.A. where MOCA is located.

On Dec. 16, 2010, anonymous street artists wheat-pasted posters of Deitch portraying him in the act of obliterating Blu’s mural. The poster depicted Deitch as an Iranian Ayatollah wielding a paint roller dripping with whitewash. As it turned out, iGreen, a group that supports the “pro-Democracy” movement in Iran through cultural work and art events, took credit for designing and posting the broadside.

A spokesperson for iGreen commented on the group’s Facebook page, “We usually keep our focus on Iran, but since there is a new Ayatollah in town we had no choice but to take a position!” The art collective appropriately titled their poster, Ayatollah Deitch.

In early January of 2011, LA RAW, a collective of Los Angeles artists, was formed to wage a street campaign against Jeffery Deitch and his censoring of Blu’s mural. On Jan. 3, 2011, dozens of artists and activists held a protest at MOCA decrying the obliteration of the mural and the commodification of street art. At that demonstration Carol Wells, founder and director of the Center for the Study of Political Graphics (CSPG), offered her summation of Deitch’s handling of Blu’s mural; “Curation is what happens before it goes public. Censorship is what happens after it goes public, and putting it up on the wall and taking it off is a clear act of censorship.”

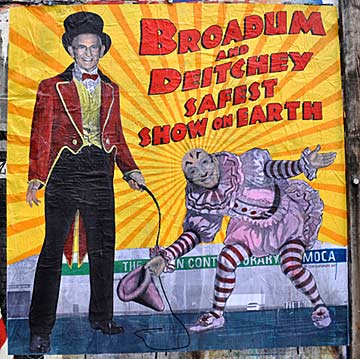

On April 6, 2011, a little more than a week before the Art in the Streets exhibit opened, an unidentified group known only as LA Anonymous added their two cents to the controversy by wheat-pasting parody posters of an old fashioned circus announcement on a downtown avenue.

The large full color print depicted billionaire Eli Broad dressed in the traditional garb of a circus ringmaster, replete with top hat and whip in hand, with Jeffrey Deitch dressed as a clown bowing at his feet. Behind the ringmaster and clown, the whitewashed wall of MOCA appears at the bottom of the poster, a reminder of the destruction of Blu’s mural. The poster’s text declared, “Broadum and Deitchey – Safest Show on Earth”, a reference to the Barnum and Bailey “Greatest Show on Earth” circus posters of old.

The week before the MOCA exhibit opened, Deitch commissioned a second mural to be painted on the very wall where Blu’s mural had been whitewashed. It does not speak well of the street art “movement” that Deitch could so easily find a group of veteran graffiti artists to assist in painting over the memory of Blu’s mural. The founding of America and the founding of the graffiti movement was the replacement mural’s rather confused theme – and what the two supposedly have in common was not clarified by the substitute mural.

Titled Birds of a Feather, the alternate mural showed a Plains Indian woman wearing a majestic eagle-feather war bonnet (in reality a headdress worn only by exemplary male warriors, each feather representing a foe humiliated or killed in battle); a copy of the U.S. Constitution upon which the words of its preamble “We the People” can be read; a 19th century steam locomotion train whose coal car is filled with spray paint cans (trains and railroads in actuality helped make possible the destruction of Plains Indian culture), and a feather quill pen scribing the edict, “What you write.” Lee Quiñones, the graffiti maven in charge of creating the wall painting, explained that the proclamation was intended to mean, “What you write is what you are, respect the movement that moves with you and for you.” Respect the movement? How is a team effort at facilitating an outrageous act of censorship any less disrespectful than the suppression of art carried out by a lone censor – Jeffrey Deitch?

At the April 17th opening of the Art in the Streets exhibit, artists and activists held a protest in front of MOCA to denounce Deitch’s censorship of Blu’s mural, but also to show their opposition to the commodification and marketing of street art. Seeing as how the museum is located in the historic Little Tokyo area of L.A., it was fitting that a major component of the protest was a performance piece based on Butoh, the unique dance-art movement founded in Japan in the late 1950s by choreographers Tatsumi Hijikata and Kazuo Ohno. Independent filmmaker James Knight videotaped the opening night protest, creating an intriguing film he titled Whiteout: Butoh for Blu. In the film’s opening, one protestor, after saying he thought highly of “90 percent of those in the show,” offered the following remark regarding the exhibit, “The question remains – who legitimizes this? Do we really need the market as the driving force in our culture?”

One of the Butoh dancers, Khadija Anderson, commented off camera: “I think it’s very dangerous to view MOCA’s reaction to Blu’s antiwar mural by erasing it as anything less than censorship. I believe not to boycott this show after the mural has been buffed would be to go against the very intention of any street art that isn’t about self-aggrandizement. The quickest way to silence dissent is to give the dissenters authority and put them on the payroll.”

On July 10, 2011, the L.A.’s arts magazine, Artillery, sponsored a debate at the Standard Hotel in downtown L.A. concerning topics relevant to this article. Some 100 people representing a wide spectrum of L.A.’s arts community attended the event. I went to hear pro and con arguments regarding: “Eli Broad: How much is too much”, and “Whitewashing MOCA’s mural: censorship or sensitivity?” Winners of the debates were decided by audience applause, and the event was moderated by Artillery magazine’s editor, Tulsa Kinney.

When Kinney began the intro to the debate, before she even finished the sentence -“MOCA’s director Jeffrey Deitch had Blu’s mural whitewashed” – there were loud boos and catcalls from a good portion of those gathered, a clear sign of audience anger towards Deitch. In the debate over the mural’s destruction, artist Anthony Ausgang argued that Deitch was within his rights to eradicate the mural, as MOCA owned the wall and Blu had received compensation. Artillery columnist Josh Herman did not even present a case against the censorship of Blu’s mural, instead he presented an off topic litany of complaints about L.A.’s art scene. Even so, when it came time to vote, the audience overwhelmingly condemned Deitch for whitewashing the mural.

Artist and former director of the L.A. Municipal Art Gallery, Mark Steven Greenfield, debated writer and Artillery magazine contributor Ezrha Jean Black on the subject of Eli Broad subsidizing or owning virtually every major cultural institution in the city. Greenfield argued that Broad was a “venture philanthropist” who sought to enhance his public image and expand his influence by controlling and manipulating the city’s arts institutions. Ms. Black took the position that in these days of austerity and shrinking government support, Broad’s money has benefited the arts. She went on to exclaim, “As to the charge that he is a manipulator, oh yeah, it is called ‘good business.'” While Black was pronounced the debate’s winner, some 40 percent of the audience agreed that Broad exercised undue hegemony over the cultural life of L.A. Needless to say, I profoundly disagreed with Ms. Black’s opinion regarding Eli Broad’s pervasive influence, and by extension, the growing domination of corporate power over the arts.

In January 2010 the U.S. Supreme Court struck down laws that banned corporations from using their vast wealth to support or oppose candidates for political office. In essence the 2010 Supreme Court decision allows corporations to pump unlimited funding into the coffers of political candidates. The outcome has been the further distortion of the democratic process by giving corporate powers the ability to openly purchase candidates and the legislative process. If it is reprehensible to short-circuit democracy by legitimating the absolute takeover of government by massive corporations, and yes, Fortune 500 plutocrats like Eli Broad, then is it not also unfitting to give control of the nation’s cultural life to those same corporate powers and tycoons?

Eli Broad and his fellow billionaires sitting on the MOCA board of directors fully expected Deitch to pull the museum out of its financial doldrums, and Art in the Streets, Deitch’s first blockbuster extravaganza at MOCA, was concocted as a spectacle to generate large crowds and even larger ticket sales. The show attracted 201,352 visitors during its 16 week run (April 17-Aug. 8, 2011); it would be the highest attended ticketed exhibit in MOCA’s history.

That long-standing capitalist anecdote, “Give the people what they want” (as if they had any real choice in the matter), is pertinent here. I do not believe the role of a museum is to provide an uncritical venue for popular entertainment, any more than I assume a library should be the repository for self-help books, fashion magazines, and cheap romance novels. Deitch’s exhibit was less a “museum survey of graffiti and street art” than it was the positioning of certain artists for acquisition at the next Christie’s and Sotheby’s private art auction (several of the artists in the MOCA exhibit were previously represented by Deitch Projects, which closed in June 2010 as Deitch became director of MOCA).

In 1750 the French philosopher Jean-Jacques Rousseau, writing in his Discourse on the Arts and Sciences, observed that “the arts spread flowery garlands over the iron chains of law, inducing consent without obvious coercion.” Rousseau’s critique seems pertinent here, given that corporate power and men like Mr. Deitch are turning the art world’s remaining shreds of autonomy and integrity into exceedingly bad jokes. As an example of the corporate patronage that has been abetted by Deitch, let us take a look at Levi Strauss & Co. and Nike Inc., both of which were major sponsors of Art In The Streets.

In 2010 Levi’s opened a temporary silk-screen workshop in San Francisco, followed by a photography workshop in New York, a film workshop in Los Angeles (located in MOCA during the street art exhibit), and finally a screen printing workshop in Berlin, Germany in July of 2011. Artists who attended the Levi’s workshops were given access to workspace, equipment, and materials free of charge. During the Art In The Streets show MOCA’s gift shop sold Levi’s denim “trucker jackets” that were emblazoned with art from various street artists, for $250 each. Now consider the following, Levi’s pays Haitian workers 31 cents an hour to manufacture apparel in sweatshops Levi Strauss & Co maintains in Haiti.

In 2009 the Obama administration fought to keep the minimum wage in Haiti to just 31 cents an hour, so that American companies like Levi Strauss, Fruit of the Loom, and Hanes could continue to reap enormous profits from Haitian workers. This is all made very clear in Haiti-related U.S. State Department diplomatic cables obtained by WikiLeaks and published by the weekly Haitian newspaper Haïti Liberté as well as The Nation. You can read excerpts of the U.S. State Department cables regarding Haiti and Levi’s at the Business Insider, Inc. website.

On July 13, 2011, the Associated Press published an exposé of the abysmal working conditions laborers suffer in Nike’s Asian manufacturing plants, where most of the company’s 1,000 factories are located. Titled Nike Faces New Worker Abuse Claims, the article noted that the 10,000 female workers at the Nike plant in Taiwan make roughly 50 cents per hour; the workers complain of being physically abused by plant supervisors (suffering kicks, scratches, and slaps), and of being fired for registering complaints. Workers in Nike’s Indonesian plants also complain of severe ill-treatment, verbal and physical abuse, extremely low wages, and arbitrary firings.

After the AP released its current findings, Nike promised “immediate and decisive action” to put an end to such abuses. Nonetheless, ever since the 1990s and the following decade, when the company was caught using child labor in Indonesia and Cambodia (involving girls as young as twelve who worked for 22 cents an hour, seven days a week, for sixteen hours a day), the sports equipment giant has said it was “taking steps” to improve working conditions in its Asian plants. It should be noted that while Nike workers in Asia are insulted, physically abused, intimidated, and paid slave wages, Nike Inc. earned $1.91 billion in fiscal year 2010. The company CEO, Mark Parker, received $13.1 million in compensation for fiscal year 2010.

While the word “groundbreaking” was often used to describe MOCA’s Art In The Streets exhibit, the elite art world’s commodification of street art has been ongoing ever since it transformed Keith Haring and Jean-Michel Basquiat into international art stars (a special section of the MOCA exhibit featured their works). The crowds of young people that attended Art In The Streets would probably be very surprised to know of Haring’s passion for the book, The Art Spirit, written in 1923 by the American painter and arts educator Robert Henri (pronounced Hen-Rye). A collection of writings and transcribed talks Henri gave to his many art students, the book opens as follows:

“When the artist is alive in any person, he becomes an inventive, searching, daring, self-expressing creature. He becomes interesting to other people. He disturbs, upsets, enlightens, and he opens ways for better understanding. Where those who are not artists are trying to close the book, he opens it, shows there are still more pages possible. The world would stagnate without him, and the world would be beautiful with him; for he is interesting to himself and he is interesting to others. He does not have to be a painter or sculptor to be an artist. He can work in any medium. He simply has to find the gain in the work itself, not outside it. Museums of art will not make a country an art country. But where there is the art spirit – there will be precious works to fill museums.”

I should add that Robert Henri was the leader of the very first avant-garde art movement in the U.S., “The Eight Independent Painters,” a group that defied the American art establishment in 1908 by painting gritty urban ghetto scenes and portraits of working people instead of saccharine canvases that glorified the wealthy ruling class. For all of their efforts “The Eight” were attacked and maligned by conservative cultural and political circles, and a hostile press christened them the “Apostles of Ugliness.”

Henri’s full statement is not only achingly beautiful, it overflows with the undeniable truth about art. While MOCA published a “comprehensive catalogue” to accompany its Art in the Streets exhibit, with a forward by none other than Jeffery Deitch, aspiring street artists would be better off reading Robert Henri’s manifesto from 88 years ago.