Smackdown! Supreme Court vs. Andy Warhol

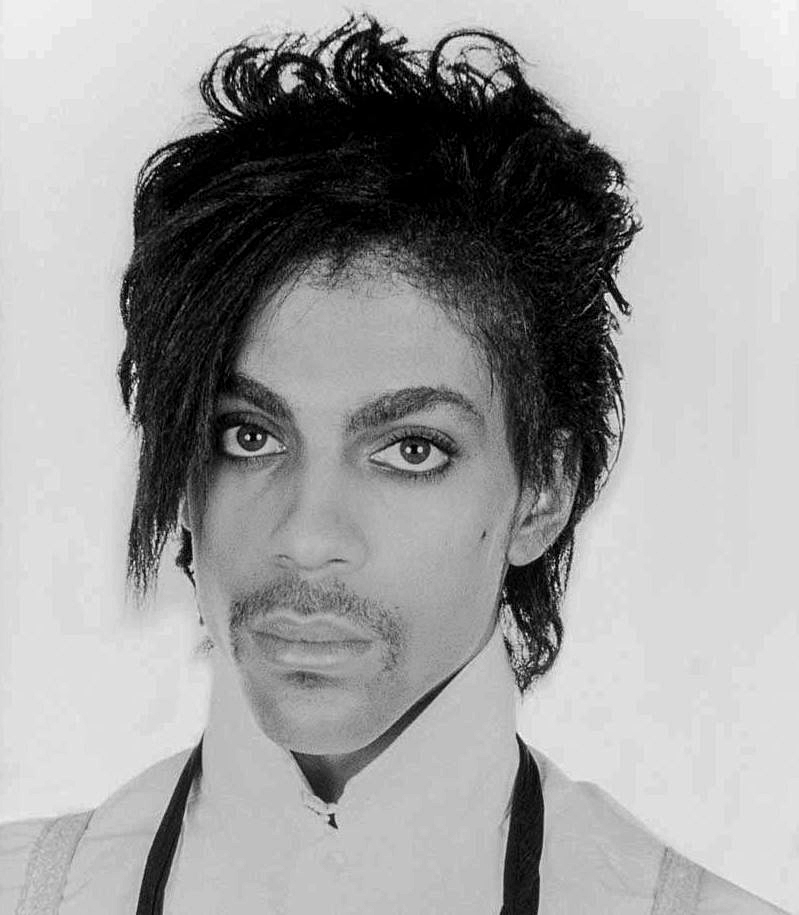

Photographer Lynn Goldsmith’s 1981 black and white photo of Prince was made just as the talented young singer-songwriter-musician was on his way to super stardom. Goldsmith’s portrait captured a moment in time with the genre-defying musician. She caught the soulfulness of the man on film.

On May 18, 2023 the Supreme Court issued a momentous smackdown to the ghost of Andy Warhol, the Andy Warhol Foundation, legions of Warhol fans, and the postmodern art world. The court case, Andy Warhol Foundation for the Visual Arts, Inc. v. Goldsmith, posed the question, did Warhol violate the copyright of Goldsmith by using her photo to create his 1984 “Prince series” of 16 silkscreen prints?

The Supreme Court ruled YES in a 7-2 landmark ruling that Warhol committed copyright infringement against Goldsmith. The ruling will have a huge impact on a contemporary art scene that has formed an unhealthy addiction to so-called “appropriation art,” or what sane people call plagiarism. There are those who call the decision an “anti-artist ruling.” As a working artist, I think that’s nonsense.

I support the “fair use” doctrine as applied to art. However, the idea of it being permissible to use portions of existing artworks to make new “transformed” imagery has became a crutch for artists who regularly appropriate the works of others. Today’s art as been subsumed by an infinite amount of poor quality appropriations. Artists should strive for originality and leave the cheap duplicating behind.

The Supreme Court majority opinion was written by the court’s liberal Justice Sonia Sotomayor, who stated: “Goldsmith’s original works, like those of other photographers, are entitled to copyright protection, even against famous artists.” She went on to remark that the majority ruling will not “snuff out the light of Western civilization, returning us to the Dark Ages.”

Liberal Justice Elena Kagan wrote the minority opinion. Along with conservative Chief Justice Roberts the two comprised the minority. Oh the irony—Sotomayor and Kagan are liberal Barack Obama nominees. In her dissent Justice Kagan said of the majority opinion:

“It will stifle creativity of every sort. It will impede new art and music and literature. It will thwart the expression of new ideas and the attainment of new knowledge. It will make our world poorer.”

How did Warhol (1928-1987) make an “expression of new ideas” by pilfering Goldsmith’s photo of Prince? Warhol simply printed Goldsmith’s photo in various colors. Seems to me Warhol’s endless plagiarizing made “our world poorer.” And yes, he had a record of plagiarizing the works of others.

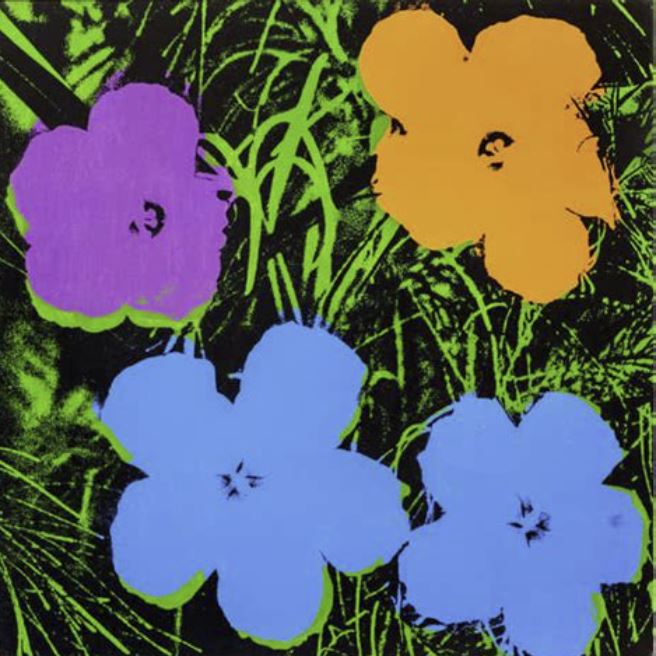

In 1964 photographer Patricia Caulfield was editor of the popular Modern Photography magazine. In a June 1964 issue the monthly published a photo of hibiscus flowers credited to Caulfield. Without permission Warhol used the photo to produce a series of silkscreen prints he titled Flowers.

Warhol printed five editions of Flowers, all in different sizes; the smallest prints were five inches square, the largest 48 inches square. These were displayed in his premier 1964 exhibit at the Leo Castelli gallery in New York City.

Caulfield learned of Warhol’s thievery and in 1966 filed a lawsuit against him for the unauthorized use of her photo. She won the case and was paid $6,000 in compensation, guaranteed royalties on future sales, and assured that future descriptions of Flowers would credit her authorship of the original photo.

But Caulfield’s court victory didn’t stop Warhol’s pilfering ways.

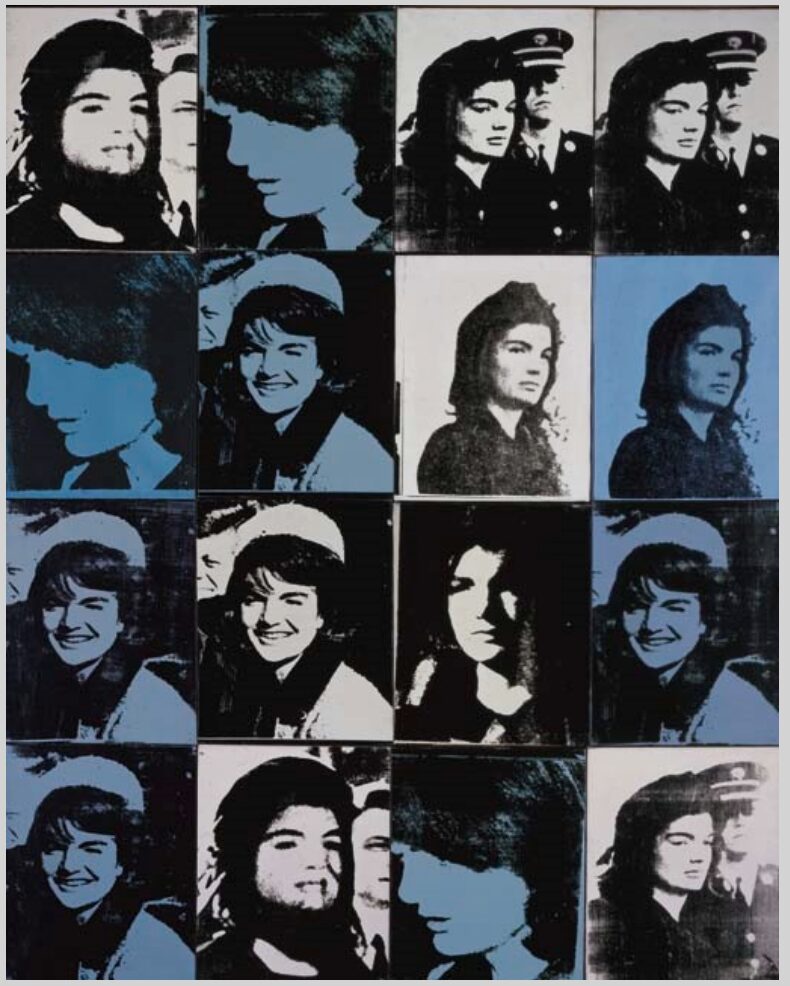

After the 1963 assassination of President John F. Kennedy, Warhol clipped a photo from Life magazine showing First Lady Jacqueline Kennedy wearing a black veil at the funeral. The photo was taken by Henri Dauman, a top feature photographer for Life magazine, a Time Inc. publication.

In 1996 Dauman read in the New York Times that Warhol sold a print titled Sixteen Jackies for $418,000. The article included a reproduction of the artwork and Dauman realized Warhol, without permission, had used his photo of Jacqueline Kennedy to create the Sixteen Jackies series; Warhol not only used Dauman’s photo, but other Life magazine photos of the funeral as well.

In 1996 Dauman and Time Inc. sued the Andy Warhol estate, the Andy Warhol Museum, and the Andy Warhol Foundation for copyright infringement. Dauman and Time Inc. settled the case out of court for an undetermined amount. A lawyer close to the case said it was “several hundred thousand dollars.”

Even after all that, in 2006 Christie’s auction house sold a silkscreen on canvas version of Warhol’s Sixteen Jackies for $15,696,000. An essayist at Christie’s had the temerity to describe the work as “one of Warhol’s great achievements.” At a 2021 auction at Sotheby’s a Sixteen Jackies silkscreen print sold for $39.9 million. I’m not certain if Mr. Dauman received any royalties from the sale.

As far as art goes, turning “out the light of Western civilization” and plunging us into the new “Dark Ages” has become an ongoing trend. When did plagiarism become accepted artistic practice? When did art schools stop teaching realistic drawing and painting? When did beauty, craft, and skill become exiled from the art world? I know it’s heretical to say, but… when did we surrender standards?

Goldsmith’s photo of Prince came from a 1981 photo shoot she did with the rocker for Newsweek. In 1984 Vanity Fair licensed one of Goldsmith’s photos for $400. It was to be used only once—as a “reference photo” for an illustration created by an artist for a Vanity Fair story on Prince. The license stipulated that the photo would not be used for any other purpose. The magazine failed to tell Goldsmith that Andy Warhol would be the illustrator.

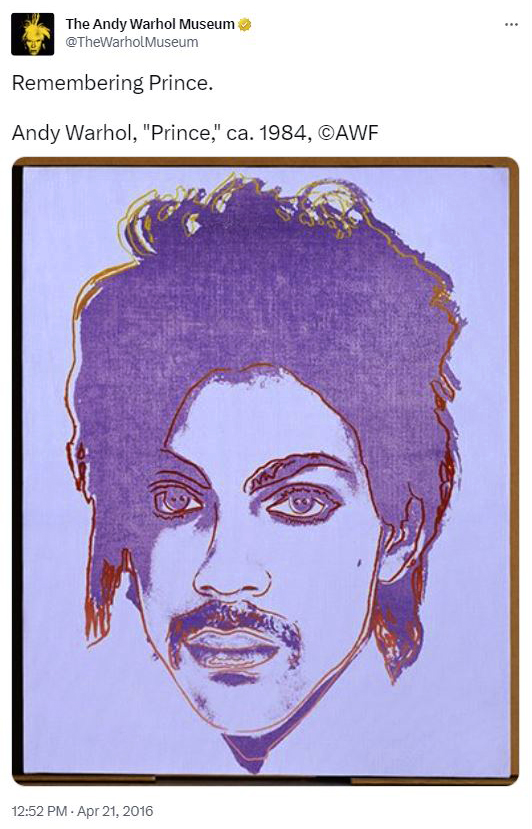

Warhol created his illustration based on Goldsmith’s photo, it was a purple colored silkscreen of Prince, and Vanity Fair published his artwork with an accompanying article in its Nov. 1984 issue—giving credit to Goldsmith for the photo. Except… Warhol didn’t produce a single silkscreen of Prince in 1984, he created an entire suite of sixteen silkscreen prints in different colors; prints Warhol called his Prince series. And all without Goldsmith’s knowledge.

Warhol died in 1987, and almost all of his works went to the Andy Warhol Foundation for the Visual Arts.

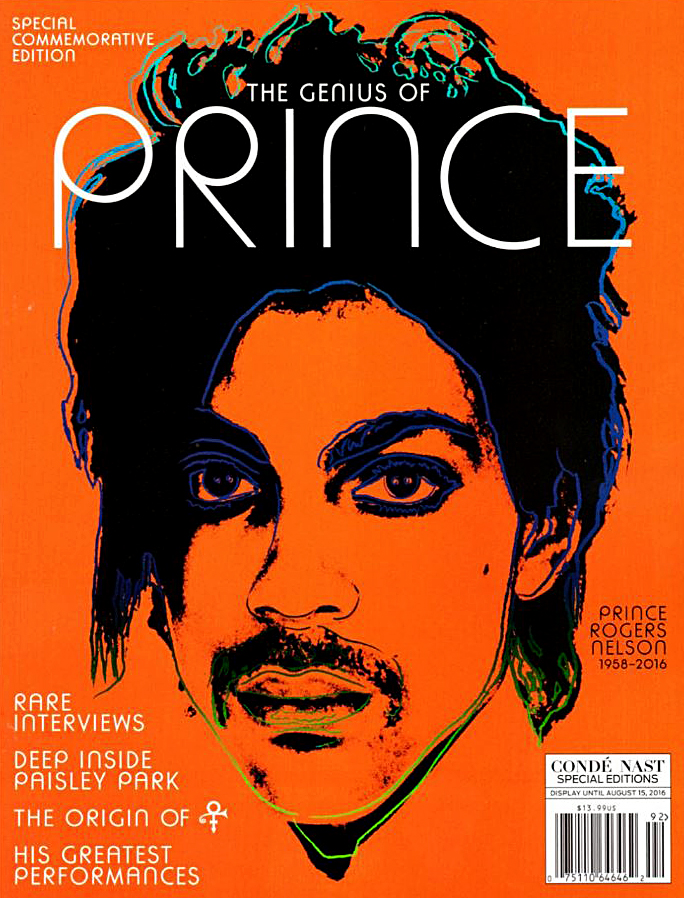

Prince died in 2016. After his passing the owner of Vanity Fair, Condé Nast, contacted the Warhol Foundation with a request to use Warhol’s 1984 Vanity Fair Purple Prince silkscreen print in a special commemorative issue on the life of Prince. The foundation offered Condé Nast any silkscreen from Warhol’s Prince series, so they chose the Orange Prince print. The foundation licensed it to Condé Nast for $10,000. Goldsmith didn’t receive a penny from the licensing.

Wait, it gets worse. Lynn Goldsmith learned of the malfeasance when she saw the Orange Prince as the Condé Nast magazine cover, along with it illustrating the publication’s article titled Purple Fame. She recognized it as her photo, but not the Purple Prince serigraph she had licensed! Goldsmith had no idea that Warhol had created 16 silkscreens from her photograph.

Goldsmith contacted the Andy Warhol Foundation to register a complaint that her copyright had been violated. Rather than resolving the problem in a civilized manner, the foundation SUED Goldsmith in April of 2017, claiming she was trying to extort the foundation. Goldsmith, protecting her rights, countersued.

In July of 2019, Judge John Koeltl of the New York federal court threw out Goldsmith’s lawsuit. Needless to say the Warhol Foundation and fans of appropriation art were giddy with joy. Koeltl supported the Andy Warhol Foundation by ruling Warhol had made “fair use” of Goldsmith’s photo. But the judge made what I thought was an odd justification for his finding:

“The Prince series works can reasonably be perceived to have transformed Prince from a vulnerable, uncomfortable person to an iconic, larger-than-life figure. The humanity Prince embodies in Goldsmith’s photograph is gone.

Moreover, each Prince series work is immediately recognizable as a ‘Warhol’ rather than as a photograph of Prince, in the same way that Warhol’s famous representations of Marilyn Monroe and Mao are recognizable as ‘Warhols,’ not as realistic photographs of those persons.”

According to Judge Koeltl, Warhol succeeded in removing “the humanity Prince embodies” from Goldsmith’s photo. A powerful, if unintended repudiation of Warhol’s work and postmodern art in general.

Goldsmith vowed to appeal the court decision and continued her battle against the Andy Warhol Foundation. She told the press: “I know that some people think that I started this, and I’m trying to make money. That’s ridiculous, the Warhol Foundation sued me first for my own copyrighted photograph.”

Goldsmith took her case to the US Court of Appeals for the Second Circuit, and that court REVERSED the 2019 ruling of Judge Koeltl. In March of 2021 the 2nd Circuit Court of Appeals found that Warhol’s Prince series did not transform Goldsmith’s photo. The court stated “the Prince series of works are substantially similar to the Goldsmith photograph as a matter of law,” and so Warhol’s silkscreens could not be considered “fair use.”

The Warhol Foundation appealed, and because appeals from the 2nd Circuit Court are heard by the Supreme Court of the United States, that’s where the case went. As the reader now knows, on May 18, 2023 the Supreme Court ruled in favor of Goldsmith, finding that Warhol had violated the photographer’s copyright when he swiped her photo to make his Prince series.

The 1964 Marilyn Monroe series was Warhol’s most iconic silkscreen prints, but the photo Warhol utilized to produce the prints was snapped by American photographer Gene Korman (1897-1978). Korman worked in the Hollywood movie industry from the 1920s to the late 1950s, taking photographs for promotional purposes, but also creating glamour photos of upcoming or established stars.

Korman took his photograph of Marilyn Monroe (1926-1962) as a promotional image for the 1953 film Niagara from 20th Century Fox. It was the first movie to give Monroe top billing as lead actor.

In 1964 Warhol purloined Korman’s photo of Monroe, cropping the image to focus on her face. He never sought permission for the photo’s usage, it certainly wasn’t licensed to him. He never paid Korman for the image. The photo was simply stolen and colorized in silkscreen by Warhol. On May 9, 2022 Christie’s auction house sold one of Warhol’s Monroe prints for $195 million. Korman’s estate did not receive any royalties from the sale. This is an example of the “expression of new ideas” Justice Kagan wrote about.

Justice Kagan likely never wondered how Korman must have felt watching Warhol raking in the greenbacks with his original photo of the late Monroe. Thanks to dollardom and its poison publicity machine, the public at large knows all about Andy Warhol… but has never heard of Gene Korman.

Media reports on the Goldsmith vs Warhol dispute referred to Warhol’s prints as “paintings.” But painting is not just applying paint to a flat surface, if so then art critics should start reviewing house painters. An artist makes prints with silkscreens, not paintings.

News accounts also suggested Warhol produced his illustration for Vanity Fair—and later on made his Prince series prints. This is a misunderstanding of screen printing. Artists don’t go through the intensive labor process of creating a silkscreen print, just to create a single copy. Silkscreen is a process that creates multiples.

Traditional screen printing utilizes fine-mesh silk stretched tightly over a wooden frame and stapled in place. That silk “screen” is the surface where the artist creates a stencil, which can be painted on, drawn by hand, or even made of cut paper. A stencil blocks the passage of paint through the screen. The wood frame holding the screen is hinged to a larger board, and lowered onto a pre-positioned sheet of paper. Paint pulled across the screen by hand with a rubber bladed squeegee, forces paint though the silk. Lift the screen and there’s the print!

Over time there have been technical innovations in screen printing; frames of aluminum, photo emulsions, screen chemicals, and polyester mesh screen are now standard fare, but the old low-tech tools work just fine in delivering complex, multicolored prints.

Warhol made silkscreen prints with basic techniques, postmodern methods, and late 20th century technologies. In 1963 he infamously said “I want to be a machine,” a comment referring to silkscreen’s mechanical precision in producing multiples. The media, especially the art press, tout Warhol for never being without a camera, but they avoid discussing his dark room tricks.

Warhol used Kodak’s “Kodalith” film to reproduce Goldsmith’s Prince photograph as a high contrast black and white photo without gray tones. That image was converted into a dot pattern, printed on acetate, and burned onto a screen with photo-emulsion, making a stencil for screen printing. With stencils that would overprint Goldsmith’s image onto screened fields of color, Warhol produced the 16 prints of his Prince series. He made all of his silkscreens in this manner.

Supreme Court decision and Warhol’s plagiarism aside, there’s a new ominous threat thundering towards artists like a train without brakes… Artificial Intelligence (AI). Nowadays to create art, non-artists and professional artists alike are using generative AI computer programs like Stability AI, DreamUp, DALL·E 2, Midjourney and Stable Diffusion. But that is another essay.

Over the years I have written several broadsides about the artist; rebukes like Warhol’s $11.7 Million Dollar Soup Can, 200 One Dollar Bills, and Andy Warhol is Still Dead. Read those essays to fully grasp what I really think about Warhol.

I was never a Warhol fan, not in the 60s when his “legendary” New York City art studio The Factory was ground zero for deep-pocketed socialites, affluent celebrities, and fauxhemian subculturalists. And certainly not in the 21st century when art world gatekeepers viewed him as an omnipotent cash cow. All that’s left is Warhol’s famous deadpan quote: “making money is art and working is art, and good business is the best art.”

Maybe the Supreme Court exposed Andy Warhol as being more of a charlatan than an artistic genius, one can only hope. But what do I know, I’m just an artist… not a Supreme Court judge.