The Death of Motor City

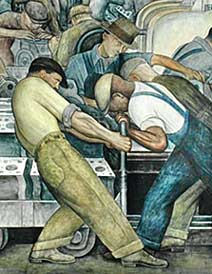

In 1932 the Mexican Muralist Diego Rivera began painting a series of 27 fresco mural panels at the Detroit Institute of Arts in Detroit, Michigan. Titled, Detroit Industry, the monumental paintings had been commissioned by the president of the Ford Motor Company, Edsel Ford (son of Henry Ford), and the director of the D.I.A., William Valentiner. The theme of Rivera’s murals was inordinately simple; the portrayal of U.S. auto workers on the factory floor utilizing the technology that made their tremendous productive capacity possible.

From Ford’s perspective the murals sang the praises of American industrial capitalism, from Rivera’s point of view they illustrated the boundless ability of the proletariat to change material reality for social good. Seventy-seven years later Rivera’s murals are still an awe inspiring wonder beyond compare – but the same cannot be said of America’s car companies.

Once the heart of the American automobile industry, the state of Michigan now leads the U.S. in unemployment at 14.1 percent. Detroit, the “Motor City”, is a wasteland and the state of Michigan is in near total collapse, a tragedy that hardly registers in the corporate media, but it is still a fact nevertheless. The Democratic Governor, Jennifer Granholm, has ordered $304 million in state budget cuts, from drastic reductions in higher education to deep cuts in social services to seniors and low-income residents. It has even been proposed that prisons be closed and state police laid-off; Granholm has already eliminated all arts funding for the state’s 2010 budget.

It is beyond the scope of this web log to explain in detail the complexities behind the downfall of Detroit’s Motor City, suffice it to say, it is the result of a very long decline. Contributing to the dilemma is the intentional de-capitalization of U.S. industrial capacity – Wall Street’s transforming the U.S. economy from one based on production to one based on financial speculation; the process of capitalist globalization that allows U.S. companies to close factories in America and re-open them elsewhere. Here it must be noted that although GM’s U.S. auto plants will be downsized and closed, its factories in China will be expanded. The Wall Street Journal reported that GM plans to build another plant in China, and to “double sales in China to more than two million vehicles and introduce more than 30 new or updated models over the next five years.”

While President Obama bailed out Wall Street bankers with hundreds of billions of dollars in taxpayer monies, he refused to do the same for GM and Chrysler; his failure to do so in essence pushed the two automakers into bankruptcy “reorganizations” – what Obama and his Auto Industry Task Force have referred to as a “new path to viability.” That path includes plant closures, a major downsizing of the workforce, the cutting of wages and benefits for workers, and the elimination of company supplied health care coverage and pension plans. The Obama plan even forced Chrysler to merge with the Italian automaker, Fiat, which assumed control of Chrysler on June 10, 2009.

Tens of thousands of auto workers are losing their jobs and hundreds of thousands of others will be affected as auto manufacturing related jobs dry up. We have been told that a revitalized American auto industry will eventually rise Phoenix-like out of this wreckage, but I seriously doubt it. The U.S. auto industry has existed for nearly a century, and it has literally changed the face of the nation, so it is disconcerting that more Americans do not seem upset by its demise. The issue of missed opportunities persists. Why did the Obama administration not invest billions into retooling ailing auto companies so that they could produce light rail public transport systems for the nation along with small fuel-efficient cars? Such a project would have kept factories open and hundreds of thousands of workers fully employed.

The question for readers of this web log is; why has there been so little response from the U.S. arts community to this current sweeping economic collapse? Save for the populist song They’re Shutting Detroit Down by country western singer John Rich, American artists have avoided the subject altogether. Social realism has deep roots in U.S. art and culture, and throughout the twentieth-century conscience-stirring works have left their mark on the nation’s psyche. After a long interruption of incomprehensible postmodernist babbling – it is time for American artists to recapture the spirit of social realism. In this context a reconsideration of Diego Rivera’s Detroit Industry mural series is in order, as the monumental works are an appropriate starting point where artists can begin to formulate suitable responses to the present crisis.

The next best thing to visiting the Detroit Institute of Arts to contemplate the significance and relevance of Rivera’s mural series is to go see the Synthescape website’s virtual presentation of those murals. Working with galleries and museums, Synthescape digitizes art collections and exhibitions, transforming them into 3-dimensional landscapes that a user can walk through using a web browser. Synthescape has created such a panorama of Rivera’s Detroit murals – and it is a breathtaking thing to behold. One can zoom in on the murals to examine the slightest details, from brush strokes to color nuances; or zoom out to study Rivera’s overall dynamic composition, which can be seen as the artist intended it – from multiple vantage points.

Rivera’s Detroit Industry murals were painted between the depression era years of 1932 and 1933, a period of great turmoil and organized labor resistance, but also a peak period for the American social realist movement in art. Rivera based his murals on sketches and photographs he made at the Ford Motor Company’s River Rouge plant, which at the time was the largest factory in the world, employing over 100,000 workers. His intent was to exalt the strength and promise of the working class, and his depictions of American auto workers brimmed over with humanist compassion and solidarity. Under the nose of management, the dignified men represented in the murals did not appear grim or downtrodden; instead, they seemed like the ones in actual command, their hands controlling the machines that would help shape the development of humankind. But Rivera’s murals were also a response to the social realities swirling around him.

U.S. auto sales were down and manufacturers responded by firing workers and cutting back operations. When Rivera started painting his homage to American auto workers, the unemployment rate in Detroit was 30%. On March 7 some 3,000 of these unemployed workers organized the “Ford Hunger March”, walking to the very factory that inspired Rivera’s mural series – the River Rouge plant. The workers attempted to deliver a petition to the company that demanded relief assistance and work. As protestors reached Gate 3 of the Ford plant, police attacked the demonstrators with tear gas and fire hoses, eventually firing live rounds at the unarmed workers, killing five and seriously injuring dozens more. Days after the massacre 60,000 citizens attended a mass funeral march to honor the slain workers.

In the aftermath of the Ford Hunger March, a series of massive labor strikes took place all across the U.S., none perhaps as relevant to Rivera’s Detroit Industry murals as the 1936-’37 Flint Sit-Down strike carried out by auto workers against General Motors factories in Flint, Michigan. Tens of thousands of workers went on strike, occupying factories and effectively shutting down GM operations until the strike was won. Flint was not only one of the greatest victories of the American labor movement; it established the strength and prominence of the United Automobile Workers (UAW), and led to the unionization of the U.S. auto industry.

In 1932 Diego Rivera wrote an essay on art for Modern Quarterly titled; The Revolutionary Spirit in Modern Art. While he did not specifically address the issues presented in his Detroit Industry mural series, his words do explain his position on the importance of a didactic art that sides with the exploited. The following excerpt from the essay explains much about his Detroit murals:

“All painters have been propagandists or else they have not been painters. Giotto was a propagandist of the spirit of Christian charity, the weapon of the Franciscan monks of his time against feudal oppression. Breughel was a propagandist of the struggle of the Dutch artisan petty bourgeois against feudal oppression. Every artist who has been worth anything in art has been such a propagandist.

The familiar accusation that propaganda ruins art finds its source in bourgeois prejudice. Naturally enough the bourgeoisie does not want art employed for the sake of revolution. It does not want ideals in art because its own ideals cannot any longer serve as artistic inspiration. It does not want feelings because its own feelings cannot any longer serve as artistic inspiration. Art and thought and feeling must be hostile to the bourgeoisie today. Every strong artist has a head and a heart. Every strong artist has been a propagandist. I want to be a propagandist and I want to be nothing else. (….) I want to use my art as a weapon.”

This article is not an appeal for artists to replicate the past, nor is it a statement made out of a sense of nostalgia. Artists today are faced with extraordinary circumstances, and the possibilities for a new contentious art are endless. It is a mistake to think of social realism as a dead art movement, rooted in the past and of no consequence to our present. The genre is no more irrelevant to contemporary society than are protests and demonstrations organized by activist citizens – in fact, both are vital and necessary if democracy is to flourish.