For Greater Glory: In the name of Christ

This article is a critique of For Greater Glory, the latest film by director Dean Wright that purports to tell the true story of the Cristero War, the armed uprising of Catholics against the Mexican government that began in 1926 and lasted until the late 1930s. Touted as a “sweeping historic epic,” the film presents only the viewpoints of the Cristeros (Fighters for Christ), an outlook that distorts a complicated period in Mexico’s history.

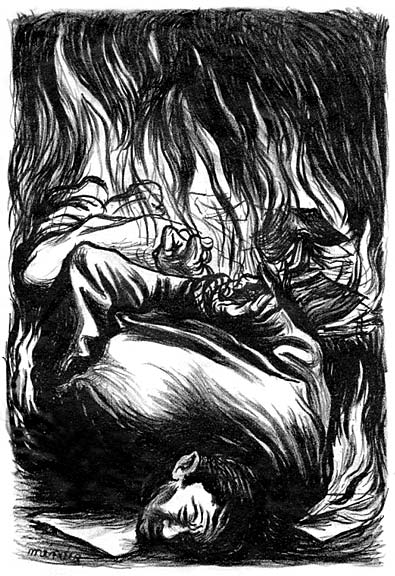

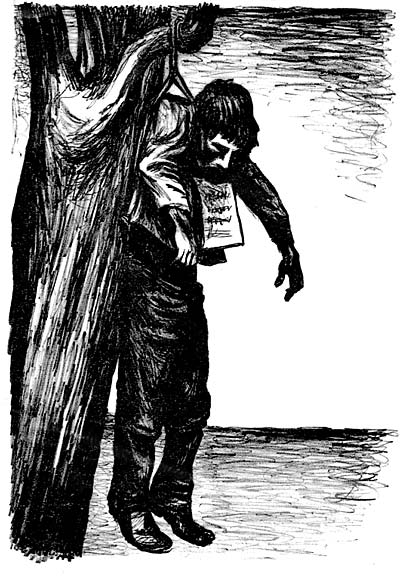

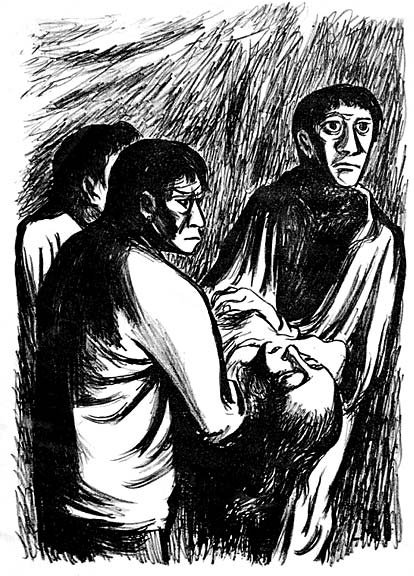

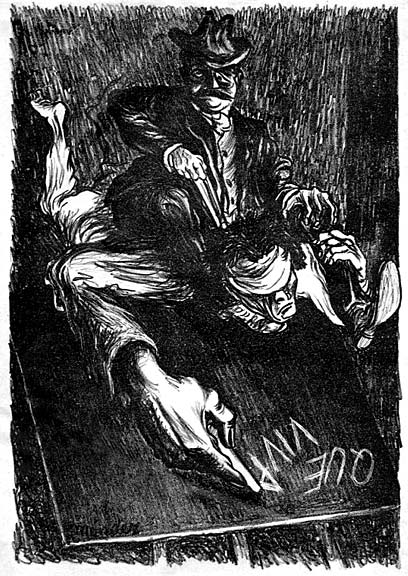

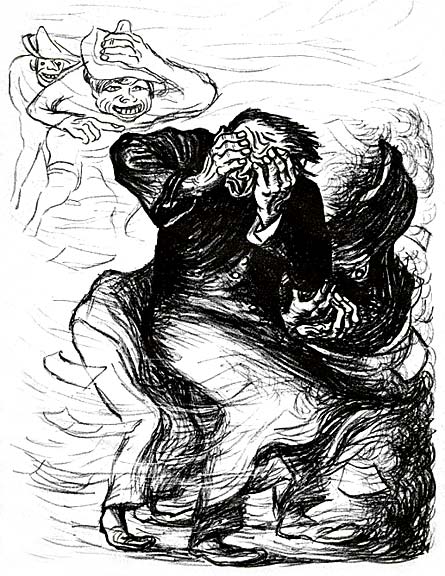

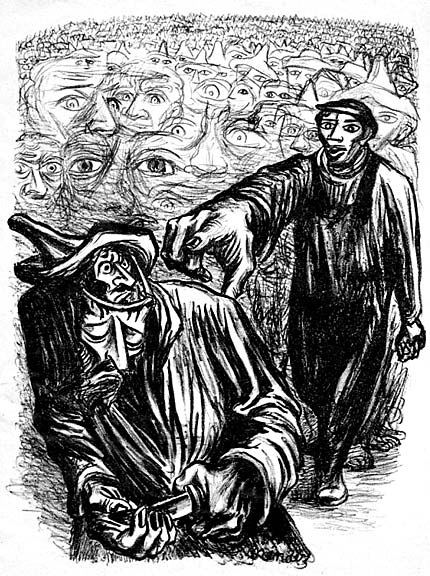

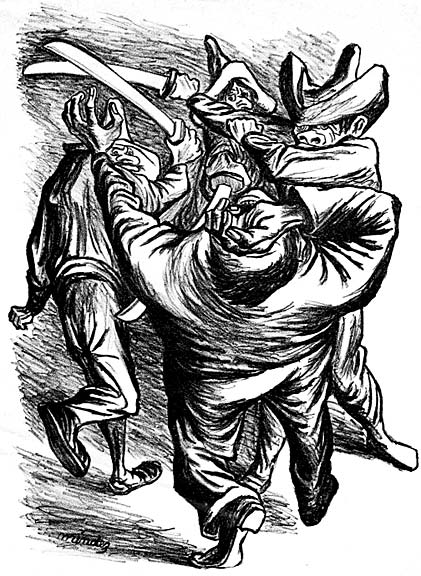

Illustrating my essay are prints by the Mexican artist and radical socialist, Leopoldo Méndez, who opposed the armed Cristero uprising and treated the War as a subject for his artworks. In particular I am featuring the artist’s lithographs En nombre de Cristo, han asesinado a más de 200 maestros (In the name of Christ: they have assassinated more than 200 teachers), a 1938 portfolio of prints by Méndez that portrayed the violence of the Fighters for Christ.

In my July 5, 2009 article, Mexican Prints at University of Notre Dame, I brought up the topic of the Cristero War when describing the lithographs by Méndez. I am highlighting his works here since they are a perfect counterpoint to Wright’s cinematic vision. Later in this article I will analyze Méndez’s prints in some detail, as well as discuss encounters other well known Mexican artists had with the Cristeros.

The first illustration in this article, a 1938 linoleum cut print titled Maestro, tú estás solo (Teacher, you are alone), is by Méndez, but it predates his In The Name Of Christ portfolio. The image depicts a teacher beset by Cristeros, who are depicted as thuggish fanatics. Two of them, a wealthy man and a peasant woman, point their fingers and hurl insults at the educator. The other two are masked hoodlums; one prepares to stab the schoolteacher with a dagger and the other aims a revolver at him. The flyer’s text reads: “Teacher, you are alone against: The white guard assassins; The ignorant fueled by the rich; The slander that poisons and breaks your relationship with the people; Fight with illustrated propaganda, an effective weapon.”

The Cristero War was triggered in 1926 when President Plutarco Elías Calles began to rigorously enforce articles in the 1917 Constitution of Mexico meant to create a secular society and crush the influence of the Catholic Church in national life. The anticlerical Calles initiated a campaign of repression against the Church and its clergy. Church property was seized and sometimes destroyed. The clergy were denied the right to vote or a trial by jury, and even prohibited from wearing a priest’s vestments in public. Those suspected of harboring support for Cristeros rebels or clergy were massacred. Needless to say the deeply conservative Catholic masses were outraged by all this, some even joined the armed Cristeros uprising.

Fighting paused when the U.S. brokered a negotiated settlement in 1929 to protect its oil interests in Mexico. Calles was president from 1924 to 1928, and dubbed himself Jefe Máximo (foremost chief). After his presidency, he in fact reigned as a shadow ruler during the “Maximato,” the period of Calles-controlled puppet presidents that lasted until 1934.

Bear in mind that starting in 1910 the Mexican people rose in revolution, overthrowing the dictatorship of Porfirio Díaz (in office from 1876 to 1911), then crushing the regime of Victoriano Huerta (in office from 1913-1914).

The Catholic Church supported Díaz and Huerta; no doubt to protect Church land holdings from the landless majority. Written by Mexico’s revolutionaries after the fall of the old regimes, the 1917 Constitution guaranteed religious freedom, but also contained articles that reduced the enormous power of the Church.

Article 3 of the Constitution eliminated Church monopoly over education. Article 130 provided for the separation of church and state. In 1926 President Calles passed the so-called “Calles Law” provisions that introduced harsh new rules aimed at the Church that destroyed religious freedom.

Anticlericalism has an even older history in Mexico. The rule of President Benito Juárez, who served as president from 1858 to 1864, was known as “La Reforma” for having restricted Church power. Juárez abolished religious courts, instituted civil marriage and nationalized cemeteries. He closed monasteries and seized Church lands without compensation, distributing the lands to landless campesinos (peasants).

For Greater Glory asserts that Mexico’s primary issue during the reign of President Calles was his attempted destruction of the Christian Church, but the larger question for the country was how it could move beyond centuries of Catholic fundamentalism to embrace science and modernity. It is no small matter to have one’s country controlled by clerics; Mexico was in the grip of theocratic ideology in the early twentieth century. While I emphatically support religious freedom, I also oppose religious fundamentalists when they seek to dominate and control others. Nevertheless, I found the hash policies of President Calles to be reprehensible.

Here I would like to mention Galileo, who was persecuted by the Inquisition in 1633 for espousing the “heresy” that the earth revolved around the sun. Proclaiming Galileo’s theories “false and contrary to Holy Scripture,” the Vatican put Galileo under house arrest where he remained until his death in 1642. Not until 2000 did Pope John Paul II apologize for the treatment of Galileo, correctly stating that “science describes the physical world and how it works,” while the Bible “describes the spiritual world.” But such an enlightened view was not held by Mexico’s Cristeros, who preferred burning down secular schools over attending them.

For his part President Calles was no less intolerant, his troops killed their share of innocents. By 1929 the Fighters for Christ killed 56,882 people, while Calles’ soldiers killed some 30,000 Cristeros. The killing however was far from over.

I must admit to a personal interest in this history. My father was born in the northern port city of Guaymas, in the Mexican state of Sonora, which was also the birthplace of Plutarco Elías Calles in 1877.

My father came to the U.S. with his mother and family in 1926; his maternal Grandfather was José María Maytorena (1867-1948), a central character of the 1910 Mexican revolution. Maytorena led insurgents against the 35-year-old dictatorship of Porfirio Díaz.

José María Maytorena became the elected governor of the state of Sonora from 1911 to 1915. By 1914 Mexican revolutionary forces had split into two camps, the “Conventionalists” (followers of Emiliano Zapata and Francisco “Pancho” Villa), and the “Constitutionalists” (followers of Venustiano Carranza and Álvaro Obregón). In 1915 the Constitutionalist and future president of Mexico, General Plutarco Elías Calles, defeated the Conventionalists forces of Pancho Villa at the Battle of Agua Prieta in Sonora. The ensuing collapse unseated Maytorena – who fled to exile in the U.S., settling in Los Angeles, California, city of my birth many years later. In 1915, after preventing the success of Zapata and Villa, Carranza took the presidency with U.S. approval, and appointed Calles military commander and provisional governor of Sonora.

When reviewing For Greater Glory, conservative critics invariably write about how the 1926 “socialist” or “leftist government” of “Marxist” President Calles attempted to crush religious liberty. Such writers draw parallels to the U.S. in 2012 and President Obama’s “war on the Church.” Notwithstanding historical records confirming Calles was not a Marxist let alone a leftist, existing realities cannot be understood by taking a set of circumstances and outcomes from the past and simply superimposing them over the present.

For Greater Glory makes no mention of José de León Toral, a Cristero fanatic who on July 17, 1928 assassinated Álvaro Obregón, who had served as president from 1920 to 1924. After the term of Plutarco Calles, Obregón was re-elected in 1928, but his murderer prevented him from taking office. The killer managed to sneak into a banquet honoring Obregón, firing five shots into the leader’s face. After Toral was tried and convicted of murder, he went before a firing squad; his final words were the battle cry of the Cristeros, “¡Viva Cristo Rey!” (Long Live Christ the King!)

A pivotal moment in the Cristero War, Obregón’s murder was left out of the film’s storyline; Toral’s terrorist act did not fit director Wright’s narrative of the Cristeros as pious, blameless, and reluctant insurgents. After Obregón’s assassination, Calles became the real power behind the next puppet president, Emilio Portes Gil.

It should be noted that director Dean Wright was the visual effects maven behind the Lord of the Rings cinematic trilogy.

Though Wright may have done justice to the characters dreamt up by J.R.R. Tolkien in that author’s late 1930s fantasy novels, his telling of Mexican history is closer to Tolkien’s flights of imagination than anything resembling an honest accounting of actual historic events. One could learn as much about Abraham Lincoln by watching Tim Burton’s preposterous Abraham Lincoln: Vampire Hunter.

The left-wing Lázaro Cárdenas was elected president in 1934, and served until 1940; it was Cárdenas that finally put an end to the power of Calles—El Jefe Máximo. A second Cristero War began in 1934 when Catholic rebels took up arms against Cárdenas, outraged that he was building schools and promoting a secular socialist education system; the In The Name Of Christ prints by Leopoldo Méndez were created during that period of crisis.

The socialist President Cárdenas wanted education to reach the most neglected areas of Mexico, providing free schools and instruction to the illiterate and uneducated. Cárdenas described his socialist education model as necessary for the development of a modern society, saying it would “spiritually liberate the working and peasant classes so that they will not remain in the hands of hypocrites and deceivers who only want to keep them in the dark, so it (socialist education) can maintain the spirit of the masses, like workers and peasants, and especially the consciousness of women and the spirit of children living in ignorance.”

Some of the Catholics fighting the Cárdenas government certainly kept unsavory allies; fighting along with them were the Sinarquistas (“those without anarchy”), a genuine fascist political party that railed in fury against Marxists and Jews. Also standing with the armed Catholics was another openly fascist organization, the Acción Revolucionaria Mexicanista (Revolutionary Mexicanist Action), commonly known as the Camisas Doradas (Gold Shirts) for modeling their golden yellow military shirts after Hitler’s Brownshirts and Mussolini’s Blackshirts.

Having become an enemy of President Cárdenas, former president Calles associated with the deeply anti-communist Gold Shirts, who staged violent attacks against Cárdenas government officials and leftists. When Cárdenas discovered Calles was plotting a coup d’état against him, he ordered the ex-president’s arrest. On April 9, 1936 when officers went to Calles’ home to make the arrest, he was found reading a Spanish translation of Adolf Hitler’s Mein Kampf. Cárdenas subsequently had him deported to the United States.

It is certainly accurate to identify Calles as an authoritarian and unyielding anti-Catholic atheist, but denying the existence of a supreme being did not make him a Marxist; those who label him along such lines only distort history.

The historian Ramón Eduardo Ruiz (1921-2010), was an author of 15 books on the subject of Mexican and Latin American history. Regarding President Calles, I take the liberty here to quote from Ruiz’s excellent Triumphs and Tragedy: A History of the Mexican People:

“As president, he tagged pernicious any revolutionary movement that attacked capitalism, welcoming foreign investors to Mexico. Barely in office, he ordered immigration officials to bar doors to ‘foreign leftists and communists,’ in 1929 severing diplomatic relations with the Soviet Union (….) The Callistas endeavored to promote capitalist growth. Their goal was to put the nation’s finances back on their feet, to repair credit standing, and to expand infrastructure.”

In 1925 Calles founded the Banco de México (Bank of Mexico), the country’s central bank and monetary authority. In 1927 he outlawed labor strikes and banned the Communist Party of Mexico, surprising accomplishments for a hard-core “Marxist.” In point of fact the Mexican left found Calles insufferable, and openly despised him.

The stance of muralist David Alfaro Siqueiros is an example of Mexican leftist opinion regarding President Calles; Siqueiros was a Marxist and a lifelong member of the Communist Party of Mexico. In 1929 he referred to Calles as having brought about “the complete submission of the Mexican government to Yankee imperialism, betraying the revolution.” In his 1932 mural Retrato del Mexico de hoy:1932 (Portrait of Mexico Today:1932), Siqueiros painted Calles as a masked armed bandit that had robbed and murdered the Mexican people. In a 1934 article written for the New Masses, Siqueiros referred to Calles as a “demagogue-hangman,” the “strong man” of the Mexican “bourgeoisie who were in league with imperialism.”

A number of reviewers wrote about For Greater Glory, but they brought little clarity to the forgotten historic episode known as the Cristero War. The movie is an empathetic and melodramatic work of propaganda. Take the word “propaganda” as a pejorative if you wish, but in 1622 Pope Gregory XV established the Congregatio de propaganda fide (Congregation for propagating the faith), the arm of the Roman Catholic Church meant to foster Catholicism; the organization’s name is the root for the word “propaganda.” Yes, the film is propaganda for the Cristeros, and a warning to those who would strangle and suppress religion.

I should mention that Los Angeles Archbishop José Gomez hosted a red-carpet premiere of For Greater Glory at the Academy of Motion Picture Arts & Sciences in Beverly Hills, California. It was reported that after the film’s screening the audience burst out with chants of the old Cristero slogan, “¡Viva Cristo Rey!” (Long Live Christ the King!)

The producer of For Greater Glory, Pablo José Barroso, is the founder of Dos Corazones Films, which describes itself as “part of a ministry that produces films to convey messages of faith and family values.”

The film was also partially financed by the Catholic Knights of Columbus (KofC). According to their website, the organization was brought “together by the ideal of Christopher Columbus, the discoverer of the Americas, the one whose hand brought Christianity to the New World.” KofC defines the organization as limited to “men 18 years of age or older who are practical (that is, practicing) Catholics in union with the Holy See.”

None of the above is an argument that the Catholic Church cannot deliver a well produced, historically accurate movie.

In 1989 the Church financed the making of Romero, a dramatic film starring Raúl Juliá that was based on the life of Óscar Arnulfo Romero, El Salvador’s Archbishop of San Salvador.

Romero was assassinated by a death squad while giving mass in a small chapel. In their zeal to defeat a communist insurgency, the U.S. backed Salvadoran army slaughtered tens of thousands of innocent civilians, including a number of Catholic nuns and priests, the highest profile victim being Romero.

Director John Duigan, with Church backing, gave an honest and straightforward account of this deplorable moment in El Salvador’s history. Clearly, two different groupings within the Catholic community delivered films with opposing points of view.

I first learned of the Cristeros as a teenager when studying the Mexican Muralist Movement of the 1930s; many of those artists had first-hand encounters with the country’s armed Catholics. In 1939 Leopoldo Méndez received a government commission from the Ministry of Public Education for artworks in support of the government’s position that all Mexicans receive a free “socialist education.” Méndez produced a portfolio of seven lithographs (shown in this article), which were then reproduced and distributed by the Cárdenas government to promote socialism and combat “religious fanaticism.” Based on newspaper reports of known assassinations, the lithographs depicted seven different educators murdered by Cristeros.

For the most part Méndez treated his subjects in a journalistic manner; a teacher lynched from a tree or hacked up with machetes wielded by Cristeros. The title of each lithograph included the exact date and place of the assassination. The prints have a surreal Goya-esque feeling about them. However, one particular lithograph stands out: Professor Juan Martinez Escobar, killed in the presence of his students in Acámbaro, Guanajuato in June 1938.

The print portrays the martyred educator as a ghost that points an accusatory finger at his assassin.

Escobar is dressed in the hat and overalls that identify a worker, driving home the artist’s message that laborers, teachers, and compesinos are united against violent religious fundamentalists.

Behind Escobar are the spirits of others killed by Cristeros; their eyes staring in condemnation from beyond the grave. Most amazing of all is the depiction of the killer, he wears a mask of Christ the Savior but he has blood on his hands. He pretends to be a Christian but is nothing more than an angry little man clutching a large bloody knife. It is little wonder why Mexican Christians in 1938 would be shocked by this artwork, as Christ is mocked as an assassin.

American artists in Mexico also witnessed first hand the armed Cristeros. Author Susan Vogel documented these facts in her fascinating book, Becoming Pablo O’ Higgins: How an Anglo-American Artist From Utah Became A Mexican Muralist. To my knowledge, Vogel’s book is the only volume to have been written about the life and times of the radical American painter and printmaker Pablo O’ Higgins, who played a major role in the Mexican Muralist Movement.

In describing encounters O’Higgins had with the Cristeros, Vogel gave a useful description of the Cristero War: “On July 31, 1926, all churches in Mexico closed and most nuns and priests left the country. Those who stayed rallied bands of devout followers, including many campesinos, who roved the countryside in packs ambushing and killing any government employees they could find, including schoolteachers.”

Vogel also quoted Mexican author Marcela Neymet, citing her work, Chronology of the Mexican Communist Party: 1919-1939. According to Neymet; “The Catholic guerrillas burned down the new government schools, murdered teachers, and covered their bodies with crude banners marked VCR, for their battle cry ‘Viva Cristo Rey!’ In April, 1927 the Cristeros dynamited a Mexico City-Guadalajara train, killing over a hundred innocent civilians. Not to be outdone, the government troops tried to kill a priest for every dead teacher.”

Vogel mentioned how the young painter Ione Robinson (1910-1989) first entered Mexico: “When eighteen-year-old Ione Robinson attempted to travel by train from El Paso, Texas, to Mexico City in June 1929, U.S. border officials discouraged her from entering the country because of the violence of the Cristeros. She learned that the rebels had control of Northern Mexico and that, although the shooting had ended, the train tracks to the capital had been blown up in places.”

A talented artist, Ms. Robinson eventually made her way to Mexico City in 1929 to help assist Diego Rivera paint his mural works at the National Palace.

In 1946 Robinson wrote her memoirs, A Wall to Paint On, in which she described meeting and working with Rivera, Frieda Kahlo, Tina Modotti, Sergei Eisenstein, Jean Charlot, and other luminaries.

She also became fast friends with David Alfaro Siqueiros, who famously painted a portrait of the young Robinson at his Taxco studio in 1932.

The Cristero rebellion was a hot topic in Mexican artistic circles, since for some time the radical arts community had been under pressure from Catholic fundamentalists.

José Vasconcelos was the visionary Minister of Education in the government of Álvaro Obregón (the president assassinated by a Cristero before he could take office for the second time). Starting in 1923 Vasconcelos commissioned the first government sponsored murals that helped ignite the Mexican Muralist Movement; a series of murals depicting Mexican history on the walls of the National Preparatory School in Mexico City. Vasconcelos contracted artists Diego Rivera, David Alfaro Siqueiros, José Clemente Orozco, Fermín Revueltas, Ramón Alba de la Canal, Luis Escobar, Xavier Guerrero, Carlos Merida, Amado de la Cueva, Fernando Leal, García Cahero, and Jean Charlot for the project.

When first beginning their murals at the National Preparatory School, the artists’ works were allegorical, but in a short time they moved towards direct political narratives; Siqueiros painted The Burial of the Martyred Worker, a scene depicting the funeral of a worker slain by hired guns of the rich, the coffin decorated with a hammer and sickle. Orozco painted some of his most brilliant and controversial murals; Destruction of the Old Order, The Trench, and Christ Destroys His Cross. Perhaps it was the latter that drove Catholics to violent action. Orozco’s Christ depicted an axe-wielding Savior come back to earth to destroy the crucifix as a symbol of authority. Catholic students soon began harassing and threatening the muralists to the degree that the artists began carrying revolvers to protect themselves. Diego Rivera famously quipped that he carried a revolver strapped to his waist in order to “orientate the critics.”

The American painter and one time assistant to Siqueiros, Philip Stein, wrote about the turmoil at the National Preparatory School in his book, Siqueiros: His Life and Works. Stein described:

“Incited by reactionary professors, fanatically religious students kept up their attempts to destroy the ‘blasphemous’ murals. Working on their murals became dangerous for the painters, and in self defense they carried revolvers. Siqueiros, painting an isolated area far from the main patio, was a principle target. When a band of more than sixty students, shooting missiles through blowguns, leveled an attack against his mural, he defended himself by firing his .45 pistol over the heads of the student mob. The loud reports reached the far-off patio alerting the thirty-odd artists to rush to the aid of the lone embattled painter. From another direction, the sculptor Ignacio Asúnsolo, his gun blazing, led a force of stonemasons against the enemy students.

A student was reported shot in the cheek, but the rioting did not end until a battalion of Yaqui Indians, soldiers of the Revolution who were camped in the patio of the nearby National Law School, arrived on the scene. When notified that the murals of the Revolution were under attack, the Yaquis had rapidly marched off to the Preparatoria and placed themselves under the command of the ex-officers, now artists. They drove off the students, and order was restored, but the damage inflicted on the murals was considerable.”

Ione Robinson meet Pablo O’ Higgins through Rivera. O’Higgins had been an assistant to Rivera since 1924. In her book, Vogel gives an account of O’Higgins doing cultural work with the Tepehuano Indians in Mexico’s Western coastline state of Nayarit in 1927. After the indigenous village was attacked by armed Cristeros, the Tepehuanos fled for their lives to neighboring Durango State with their casualties. In Durango, O’Higgins saved a wounded Tepehuano boy by removing a Cristero bullet from the child’s leg. When the Tepehuanos asked O’Higgins what they could do to thank him, the artist gave the indigenous people sheets of paper and asked them to create drawings for him. According to Vogel, “upon his return to Mexico City, Pablo presented the drawings to the government because he believed they belonged in a museum where everyone would be able to see them.”

Well acquainted with the chronicles of Mexico’s history, I am annoyed by the simplistic telling of the Cristero War as portrayed in For Greater Glory. The history of a nation is always an incredibly complex affair; if there is a country other than Mexico with a more byzantine record of historic characters and events, one would be hard pressed to name it.

Keeping that in mind, Hollywood rarely, if ever, manages to produce films that accurately portray the twists and turns of historic events; especially so today with current U.S. cinema having been reduced to an endless run of mindless, computer generated, big-budget comic book spectacles. As the film industry targets the “Hispanic market” with works providing little insight into Mexican culture and history, movies like Dean Wright’s For Greater Glory, and Julie Taymor’s 2002 Frida, it is vital to maintain a critical view of Hollywood productions.

This treatise only begins to scratch the surface of the Cristero War and the social forces that either gave rise to it or opposed it. Some of Mexico’s artists, who happened to be leftists, left a clear record of their opposition to the Catholic Church; the makers of the 2012 film For Greater Glory, tout it as “the true story of Cristiada.” The truth lies somewhere in between.