Ray Bradbury, Flame of Metaphor & Myth: R.I.P.

Ray Bradbury, the great writer of science fiction, fantasy, and mystery stories, died on June 5th, 2012 at the age of 91. Born in Waukegan, Illinois, Bradbury came to the City of Los Angeles with his parents in 1934, where he settled permanently to become one of the city’s illustrious adopted sons.

A favorite author of mine, Bradbury penned numerous short stories and novels, but it was his 1953 dystopian novel Fahrenheit 451 that continues to haunt me.

Written in the year of my birth, Fahrenheit 451 tells the chilling tale of a future American society where the population is kept under control by the uninterrupted broadcasting of frivolous entertainment; in which endless trivial amusements and diversions are found on giant TV screens located in all public and private places.

Instead of extinguishing bonfires, the state’s well organized and omnipotent firemen ignite them; the firemen burn books, all of which have been banned. The libricide helps to cultivate the ignorance and anti-intellectualism that the government counts on to prevent dissent.

Yet, Bradbury always insisted that Fahrenheit 451 was not so much about government oppression as it was about the dangers television posed to the written word; that and how easily people embrace mind-numbing conformity. In 1966 director François Truffaut produced a compelling film based upon Bradbury’s prescient tale.

I do not intend this article as an obituary for Mr. Bradbury, that can be found elsewhere; the L.A. Times published a notice of his passing, as did the L.A. Weekly and likely many others. Rather, this commentary will reveal one of the long forgotten episodes of Bradbury’s memorable career, his collaboration with artist Joseph Mugnaini (1912-1992), a fabulous L.A. artist that illustrated several of Bradbury’s books.

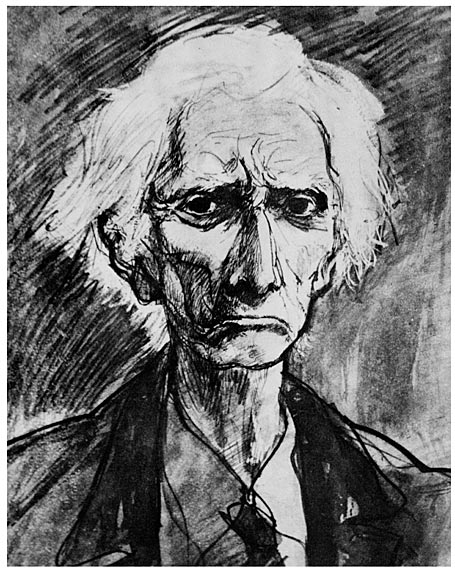

As fate would have it, I was a student of the irascible Mr. Mugnaini when he taught printmaking at L.A.’s Otis Art Institute in the early 1970s.

Brilliant and short-tempered, Mugnaini was an intimidating figure, but he was also a superlative and inspired printmaker that I learned a great deal from; an unforgettable character, he possessed a rugged face that is forever etched in my mind. One day in class Mugnaini gave me one of his etchings, Baroque with Red Mama. I still have the print in my collection.

Born in Italy, Joseph Mugnaini moved to the U.S. with his family when he was but an infant. He grew up in L.A. and attended Otis Art Institute in 1940-1942. After serving in the Army during WWII, he returned to L.A. and became an instructor at Otis, where he remained as a professor and head of the Drawing Department until he retired in 1976.

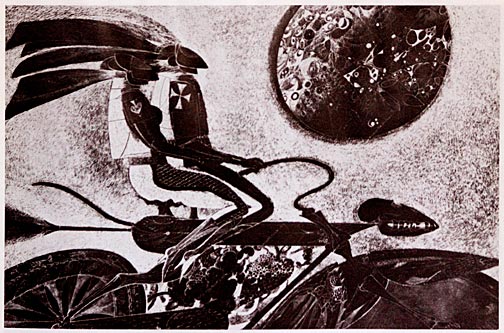

Mugnaini created the illustrations for Icarus, a 1962 animated film based on a story by Bradbury; the short film was nominated for an Academy Award (you can view the entire film on YouTube).

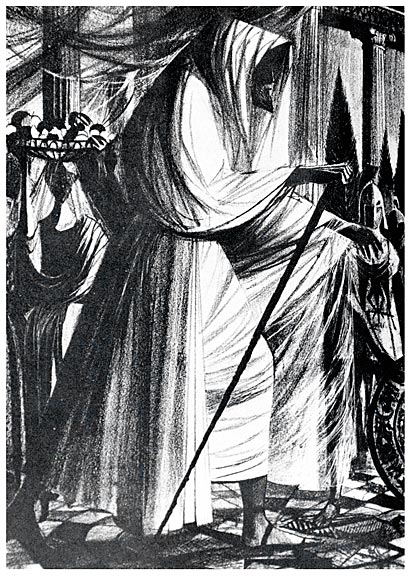

Aside from his collaborations with Bradbury, Mugnaini was a multifaceted artist that eschewed abstraction, favoring a loose and fanciful style of realism when creating his drawings, paintings and prints. His narrative works were filled with references both historical and literary.

Needless to say Mugnaini’s adherence to realism, however whimsical, put him at odds with the art establishment, at the time slavishly devoted to non-objective abstract expressionism, and later the lowbrow offerings of Pop art.

Mugnaini also wrote several textbooks on making art, including: Drawing: A Search for Form (1965); Oil Painting: Techniques and Materials (1969); and Hidden Elements of Drawing (1974). His works are found in the collections of the Library of Congress and the Smithsonian Institution.

In this essay, Bradbury himself will have the last words on Joseph Mugnaini. Bradbury’s remarks were published as the foreword to the 1982 book, Joseph Mugnaini: Drawings and Graphics, a compendium of various artworks by Mugnaini. Four artworks from that book illustrate this article. Like a character in Bradbury’s Fahrenheit 451, I have memorized passages found in Mugnaini’s books, reeling them off publicly as an act of resistance against a society so dumbed down that masses of people cannot survive without “tweeting” about the latest pop culture gossip. The words are now passed on to you. Bradbury’s praise of his artistic collaborator are as follows:

“The custom of artist-illustrator and mythologist (which is what a good writer should be) working together is as old as the Greeks, Romans, or name any other culture of some two-thousand-plus years ago. They are amiable cross-pollinations of one another. The history of literature and art is full of these fabulous speaking-writing-painting children. And indeed they are children, for if they are not that first, they cannot be the wild creatures that seize and freeze life, later. The sad thing about the cultures of the twentieth century is that often, perhaps because of Abstract Art lumbering on the scene and crushing Metaphor and Myth under its nihilistic rump, we have had little bedding of artists and tellers of tales. Our art galleries hence have been filled with sound and fury, signifying nothing.

Joe Mugnaini and I have tried to revive the ancient tradition. It all came about by accident, some twenty-nine years ago. Passing a gallery late at night, I saw a lithograph of an old house, the sort of place a beast like myself might want to live in. With what little money I had, I rushed to buy the print the next day, and saw, on the walls, yet further metaphors of ideas and stories much like those inside my head, but not yet put down on paper. Who is this genius, I asked myself, who clones my concepts, without ever having met me? The answer was: Joe Mugnaini, of course. I went to see him, bought his paintings, got him to paint the cover and do the interior illustrations for my next book, The Golden Apples of the Sun, and the rest is a damn jolly good history of friendship and collaboration.”