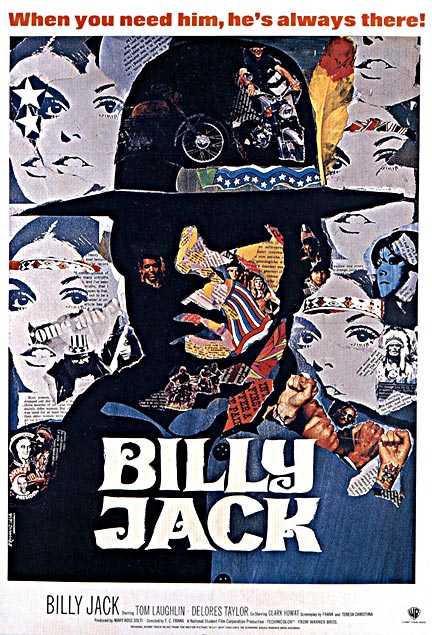

Billy Jack

I was 18-years-old when the movie Billy Jack was first shown in US theaters in the year 1971. Tom Laughlin, the man that imagined, wrote, starred in, and independently produced the film, died on Dec. 12, 2013 at 82 years of age.

This is a short remembrance of Mr. Laughlin, an appreciation for his swimming against the tide and capturing a certain spirit that most today will deny ever existed.

I cannot begin to say how influential Billy Jack was to my generation.

As the Vietnam War continued to rage in 1971, US Army Lieutenant William Calley was found guilty of mass murder for his role in the My Lai massacre; the Pentagon Papers were published in the Washington Post and the New York Times; prisoners took over Attica State Prison in Attica, New York and the government responded by launching a military assault that killed 28 inmates and 9 guards. Over 1,000 Vietnam War veterans threw away their combat medals and ribbons on the Capitol steps in a protest against the war, and the Native American occupation of Alcatraz ended when armed agents of the state forcibly removed the indigenous activists from the island. Of course, there were dozens of earthshaking events that took place in 1971, but the aforementioned sets the stage for an understanding of Billy Jack.

None of the corporate press obituaries written for Mr. Laughlin will tell you this, but Billy Jack was one of the cultural expressions of opposition to illegitimate power that became a hallmark of the rebellious late 1960s and early 1970s. Laughlin’s movie embodied the anger, distrust, and open contempt millions of young Americans came to feel towards government.

The character of Jack can be described as a Green Beret Vietnam War veteran of white and Native American heritage that experienced the horror of war and came home to a deeply divided nation.

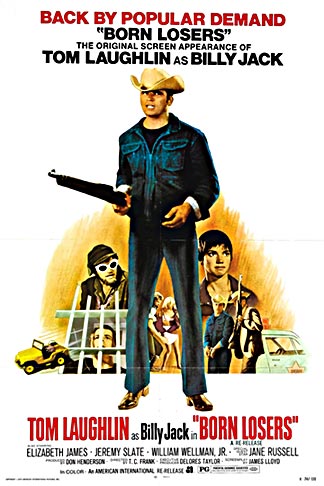

Confronted with this division, Jack found his spiritual core by becoming a guardian of the people. The character of Billy Jack first appeared in Laughlin’s 1967 Born Losers, where Jack battled a psychopathic motorcycle gang that had been terrorizing a small California beach town.

Nevertheless, Jack as a character cannot in any way be compared to vigilante characters like those in Death Wish (Charles Bronson), or Dirty Harry (Clint Eastwood). As a Vet, Jack certainly had no relationship to the monosyllabic, muscle-bound, jingoistic Rambo (as played by the monosyllabic, muscle-bound, jingoistic Sylvester Stallone).

The character of Billy Jack really struck a nerve in the 1971 film, where the tale of the battle hardened Vet takes on a decidedly anti-authoritarian direction. In the film Jack rediscovers his Native American roots while living on an Arizona reservation, he takes up the struggle to defend an alternative school and its hippie and indigenous student body from small town bigots, and uses his hapkido martial arts and firearms skills to battle the forces of oppression on his native soil.

The movie more than touched upon pertinent social issues from an egalitarian perspective; racism, the abuse of power, and other pressing concerns, some of which are still with us in the present day. The film ends with Jack entering an armed confrontation with law enforcement and their crooked bosses in city government, leading to his arrest and imprisonment. In other words, Billy Jack is not a movie that would be made today.

In the ending scene of the film Billy Jack is driven off to prison in a column of police cars, his young supporters line the road with their clenched fists held high in defiance of authority. The song One Tin Soldier played over the movie’s final moments. The song as recorded by the US rock band Coven put the finishing touches on the movie’s pro-freedom stance and further galvanized the real world antiwar movement. One Tin Soldier hit number 17 on Billboard’s top 100 in 1971.

Laughlin’s 1971 Billy Jack would be followed up in 1974 by The Trial of Billy Jack and again in 1977 with the last of the series, Billy Jack Goes to Washington. All took the same dissident stance, but I think the original 1971 version was the most effective and influential. The last film condemned the atomic power industry and its connections to the US government; Laughlin remained convinced that his film did not receive a general theatrical release because of government efforts to suppress it.

Commenting on the film’s portrayal of governmental collusion with corporate power, Laughlin told Sacramento TV interviewers in 2007, “However corrupt you think Washington and Congress are… you’re not even close.” Little has changed since then.

While you might well bemoan Billy Jack as just so much whining from Hollywood liberals, Tinsel Town didn’t exactly roll out the red carpet to Tom Laughlin and his antiwar protagonist. The Billy Jack films were produced independently, and Laughlin used his own money to make them. In the case of the 1971 Billy Jack, its politics caused major studios to reject it, but Warner Bros. finally worked up enough courage to distribute it. However, Warner dragged its feet in promoting the movie and Laughlin had to wage a three year legal battle to regain control of his film.

Laughlin finally won his lawsuit, and in 1973 rented 1,200 movie theaters across the US for the re-release, a strategy that had never been used previously. While the 1971 Warner distributed release made $6 million, Laughlin’s independent ’73 re-release eventually made $100 million. Billy Jack remains one of the biggest grossing films in the history of independent filmmaking.

Billy Jack would also be the first film to introduce a mass US audience to martial arts, something that forever changed the American understanding of “action” movies. Billy Jack predated the films of the Chinese American martial artist, Bruce Lee.

Tom Laughlin was a student of the Korean martial art, hapkido, and he trained a great deal for the fight scenes in his film.

While Laughlin did his own stunt work in the movie, he called upon the Korean grandmaster, Bong Soo Han (1933-2007), to stand in as Billy Jack to perform the advanced fighting techniques seen in the most electrifying and memorable fight in the movie.

Despite the popularity of the Billy Jack films, critics generally hated them. For instance, Roger Ebert (1942-2013) reviewed Billy Jack by stating, “I’m also somewhat disturbed by the central theme of the movie. ‘Billy Jack’ seems to be saying the same thing as ‘Born Losers,’ that a gun is better than a constitution in the enforcement of justice.” Other bourgeois film critics have referred to the films as “vigilante-themed” (LA Times 12/15/2013). In its obituary for Mr. Laughlin, USA Today made reference to his “big-screen vigilante Billy Jack.”

The Merriam-Webster definition of the word vigilante is that of “a person who is not a police officer but who tries to catch and punish criminals.” In an opening scene from Billy Jack, Jack discovers the town’s corrupt unelected political boss, Mr. Stuart Posner (played by Bert Freed), trespassing onto the reservation with his thugs to hunt and kill wild horses. Jack confronts the armed goons with his own lever action rifle and the following dialog ensues:

Jack: You’re illegally on Indian land.

Posner: I’m sorry about that. I guess we just got caught up in the chase and crossed over without knowing it.

Jack: You’re a liar.

Posner: We got the law here, Billy Jack.

Jack: When policemen break the law, then there isn’t any law – just a fight for survival.

The exchange between Jack and Posner does suggest vigilantism, but would it not be more accurate to describe Posner as the vigilante? As the unofficial “leader” of the town, he appointed the judges and the police, so when he said “We got the law here,” he literally meant that he was the law.

Another scene from the Billy Jack film shows hooligans associated to Posner, roughing up Native American students at a local eatery. Billy Jack walks into the establishment just as the racist brutes are dumping white flour on the students in a mocking attempt to make them “white.” Tensely, Jack tells the bullies that he has tried to “be passive and nonviolent,” but when he sees the children he loves so abused by “the savagery of this idiotic moment of yours… I go BERSERK!” Jack then trounces the racists with a series of hapkido punches and kicks, utterly vanquishing them before attending to the stricken kids.

To fully understand that scene, one must know that just eight years earlier on May 28, 1963, multi-racial Civil Rights demonstrators had staged a sit-in to desegregate a “Whites Only” lunch-counter at a Woolworth’s Department Store in Jackson Mississippi. The protestors were viciously assaulted by a gang of white racists, while the police stood by and watched. Those conducting the sit-in were punched with brass knuckles and struck with broken sugar containers. They were burned with cigarettes while the mob poured sugar, ketchup, mustard, and drinks on them. A photo of the attack made the national news, outraging people everywhere; Laughlin was one of those people.

All this brings up memories of the Deacons for Defense and Justice. The Deacons were founded in Jonesboro, Louisiana in 1964 by African American men wanting to protect their communities from the depredations and terror of the Ku Klux Klan.

A good number of the Deacons were combat veterans of WWII and the Korean War, they armed themselves with legal firearms and patrolled their neighborhoods, guarding against the KKK. The Deacons for Defense and Justice provided security for the non-violent activists of the Congress of Racial Equality (CORE), who were organizing voter registration drives among disenfranchised blacks. Considering that law enforcement, the courts, and various governmental agencies in Louisiana at the time were largely controlled or sympathetic to the KKK and other white supremacist organizations… can you really call the Deacons “vigilantes”?

I am struck by the vast difference between the tone and temperment of the Billy Jack movies, and contemporary movies like Kathryn Bigelow’s The Hurt Locker and Zero Dark Thirty, films that not only embrace torture and imperial intervention, but were made with the cooperation of the Pentagon and the CIA. Today’s critics have nothing but praise for such films, and would never express their being “disturbed” that “a gun is better than a constitution” when depicting the invasions of foreign countries or holding “enemy combatants” in torture centers.

Even the liberal windbag Michael Moore praised Zero Dark Thirty as a “fantastically-made movie” that should “make you happy you voted for a man who stopped all that barbarity” (referring to then President Obama). And what barbarities had been halted exactly? Launching war without Congressional approval? Zapping wedding parties with drone missiles?

It should be remembered that in 1968 John Lennon wrote an alternative version of his song Revolution that included the line, “we all want to change the world, but when you talk about destruction, don’t you know you can count me out/in.” Lennon included the word “in” because he was torn over whether violence might actually be used successfully to bring about justice. Tom Laughlin did not share those misgivings, and his anti-hero character of Billy Jack used his open heart, swinging fists, and gun, to fight oppressors and protect the defenseless.

Like many films from the period of the late 1960s and early 1970s, the Billy Jack movies are undoubtedly dated. This is due, not only to the technological changes that have taken place in the world of movie making, but because of the changing perceptions and sensibilities of today’s film makers. Yet, an authentic and deeply felt humanism still emanates from Laughlin’s Billy Jack series, no matter how dated they may appear, which is something no one will honestly be able to say about all of Hollywood’s current action films rolled together.

Laughlin’s films could have been improved with substantial edits to focus the stories and shorten running times, though I say that about most films from the period. Just as postmodernism reduced the visual art world to an uncommunicative, detached, and indifferent state, so too has Hollywood largely forgotten how to tell the human story realistically and sympathetically. Laughlin could at least write a screenplay that expressed real compassion, despite the fact that he was not the most sophisticated or accomplished director. In a 2011 video statement titled What makes the Billy Jack films so unique?, Laughlin admonished Hollywood filmmaking by proclaiming:

“Another thing that made the Billy Jack series so unique, and so box office goldmine, is that you had the super action, the morality, the spirituality… come from both a super hero, Billy Jack, and a super heroine, Jean – who does credible, powerful women’s action, not absurd stuff like shooting two guns while riding backwards on a motorcycle, as Cameron Diaz did in the latest Tom Cruise picture… just absurd stuff.”

Whatever the weaknesses of Tom Laughlin as a director, and there were many, I would prefer his vision over most anything Hollywood offers today.