Mexican Prints at University of Notre Dame

The prints of the Mexican Taller de Gráfica Popular (TGP – Popular Graphic Arts Workshop), are being presented at the Snite Museum of Art at the University of Notre Dame, Indiana from July 12, 2009 to September 13, 2009. Titled Para la Gente: Art, Politics, and Cultural Identity of the Taller de Gráfica, the exhibition presents forty prints created by artists who worked in the TGP print collective in Mexico City from the mid-1930s to the early 1950s. Internationally known for their highly-political prints, the TGP workshop generated woodblock, linoleum, and lithographic prints that remain unparalleled to this day.

I first discovered the TGP as a teenager in Los Angeles during the late 1960s. For Chicanos, TGP prints provided an exciting touchstone with Mexican art, culture, history, and politics, but in general the artworks also offered universal insights into the human condition – revealing the hidden class dimensions behind issues of poverty, repression, and war. Sometime in the early 1970s I acquired a copy of 450 Años De Lucha: Homenaje Al Pueblo Mexicano (450 Years of Struggle: Homage to the Mexican People), a significant portfolio of prints by twenty-five TGP artists that vividly recounts the history of the Mexican people.

Published by the collective in 1960, 450 Años De Lucha is actually a soft-cover unbound “book” that contains 140 reproductions of prints by artists such as Leopoldo Méndez, Pablo O’Higgins, Alberto Beltrán, Mariana Yampolsky, Alfredo Zalce, Luis Arenal, and Elizabeth Catlett. The prints originally served as street flyers and posters for the political instruction and edification of an illiterate population, and tens of thousands of copies were widely distributed. The free prints were literally – Para la Gente (For the People). As a radical chronicle of Mexico’s entire history, the remarkable print portfolio covers everything from the 1519 heroic Aztec resistance against the Spanish Conquistadors (Cuauhtemoc – Leopoldo Méndez), to a woodblock print celebrating the nationalization of Mexico’s mineral wealth in 1960 (Hacia La Nacionalizacion de la Mineria – Jesus Escobedo).

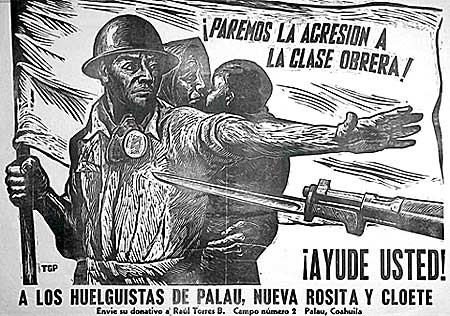

A focal point of the Snite Museum exhibit is a linoleum block print by Leopoldo Méndez, Paremos la Agresion a la Clase Obrera. Ayude Usted. A los Huelguistas de Palau, Nueva Rosita y Cloete. (Let us Stop the Aggression toward the Working Class. Help the Strikers of Palau, Nueva Rosita, and Cloete). Méndez created the print in 1950 as a street poster calling for solidarity with mine workers in their strike against the U.S. owned company, Mexican Zinc Co. The print is a consummate example of the combative spirit that motivated the TGP collective.

The workers at the Nueva Rosita, Palau, and Cloete mines in Coahuila, Mexico, organized for humane working conditions, decent pay, and union representation, and when they went on strike against Mexican Zinc, the company retaliated by firing the strikers and hiring strike breakers. The Mexican government declared the area under martial law and sent in the army. Union leaders were arrested, the union’s treasury was seized, and union activity banned. The mine company controlled the food supply stores and health care facilities in the strike area, and used that control to crush the worker’s strike by closing down vital services. Around 4,200 striking miners responded by staging a “Caravan of hunger” march, walking more than 400 miles to the capital behind a flag emblazoned with the image of the Virgin de Guadalupe. After walking for 50 days to present their case to Presidente Miguel Alemán, and rallying tens of thousands in the nation’s capital, Alemán declared the strike illegal. The defeated miners were sent back on trains to their hometowns and the strike remained unresolved.

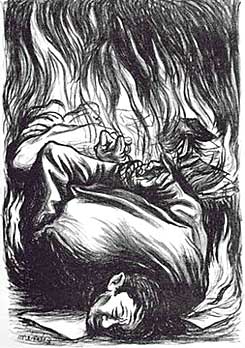

A particularly moving and provocative series of prints by Leopoldo Méndez not displayed at the Snite Museum is the artist’s, In The Name Of Christ: They Have Assassinated More Than 200 Teachers (En Nombre De Cristo: Han Asesinado Más De 200 Maestros). The prints have to do with the counter-revolutionary “Cristero War” of 1926-1929, when fundamentalist Cristeros (“fighters for Christ”) launched an armed rebellion against the Mexican government because of the anti-clerical Mexican Constitution of 1917.

Reformists had worked for a secular democracy that would reduce the Catholic Church’s enormous land holdings as well as end their stranglehold over education; but fundamentalists took up arms in 1926 when Presidente Plutarco Calles began to strictly enforce anti-clerical provisions of the constitution. Religious zealots were vexed by enforcement of provisos like Article 3, which states – “education shall be maintained entirely apart from any religious doctrine and, based on the results of scientific progress, shall strive against ignorance and its effects, servitudes, fanaticism, and prejudices.” However, fundamentalists were most irritated by Article 130, which “States that church(es) and state are to remain separate.” By the time the conflict ended in 1929, some 90,000 people had perished in the violence.

In 1939 the administration of Presidente Lázaro Cárdenas (1934-1940), commissioned Méndez to create a portfolio of seven lithographic prints on the subject of educators who had been murdered by Catholic fundamentalists during the Cristero uprising. The resulting lithographs commemorated seven different teachers who had been brutally slain by religious zealots, depicting the teachers under threat, in the throes of death, or after they had been assassinated. In the lithograph shown above, Méndez portrayed the gruesome killing of Professor Ramón Orta del Río in Nayarit, one of Mexico’s 31 states. The killers doused the body of their victim in gas and set him on fire.

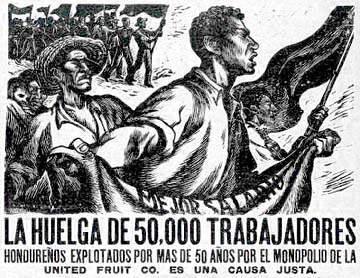

Created in 1955, Alberto Beltrán’s original linoleum-block print (above) was reproduced as a poster expressing solidarity with striking workers in Honduras. Since the early 1900s U.S. companies totally controlled Honduran agricultural production and exports, largely based upon the cultivation of bananas, making Honduras the original “Banana Republic.” The Standard Fruit Company and the United Fruit Company – both U.S. businesses – virtually ran the country. It was the president of United Fruit, Sam Zemurray, who infamously said of Honduran officials; “A mule costs more than a deputy.” From 1903 to 1925, the U.S. Marines intervened in Honduras no less than seven times. After decades of ferocious exploitation by U.S. commercial interests, Honduran banana workers staged a historic strike for better working conditions and higher pay that began on May 1, 1954.

Beginning in the north coast town of El Progreso, the strike lasted around two months and involved over 14,000 banana company workers. The work stoppage quickly paralyzed other port towns dominated by U.S. companies, eventually spreading to the capital Tegucigalpa. Workers from other industries went on strike in solidarity with the banana workers, with some 40,000 workers eventually joining the labor action. Activists throughout the hemisphere supported the Honduran workers, and it was at the highpoint of the great strike that Alberto Beltrán created his print, which he titled: La huelga de 50,000 trabajadores hondureños explotados por más de 50 años por el monopolio de la United Fruit Co., es una causa justa (The strike of 50,000 Honduran workers exploited for more than 50 years by the monopoly of the United Fruit Co., is a just cause). Despite harsh repression from the U.S. companies and their paid-off government lackies, the striking workers were victorious and won their major demands.

Beltrán’s Honduran solidarity poster could not be timelier considering the military coup in Honduras at present. If the TGP collective were still in existence it would surely react to the current putsch with fierce condemnation. While President Obama expressed “great concerns” regarding President Zelaya being toppled by the military, the Los Angeles Times noted that:

“U.S. officials did not demand the reinstatement of Zelaya. The administration left its ambassador to Honduras in place, while several governments in the region recalled theirs. And despite control over millions of dollars in aid and massive economic clout, the administration did not threaten sanctions or penalties against Honduras for the formation of a new government the day after Zelaya was dragged from his bed and removed from the country Sunday. Before Sunday, Obama administration officials were aware of the deepening crisis and said they spoke to Honduran officials in the hope of resolving the dispute and averting a forced transfer of power.”

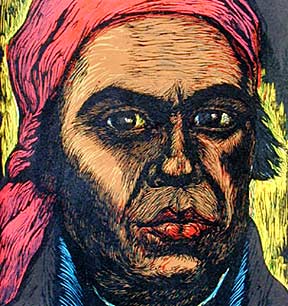

TGP artists focused their considerable artistic skills upon real world outrages like wars and military coups, and there is hardly an offence they did not address through their art, but they also busied themselves with creating sympathetic, dignified, and evocative portrayals of the broad masses of the Mexican people; their labors, aspirations, discontents, and advancements.

In the “Declaration of Principles” published in their 450 Años De Lucha portfolio, the Taller de Gráfica Popular artists proclaimed that their works were part of the “constant struggle to help the Mexican people defend and enrich their national culture, independence, freedom, and peace.” Those principals will undoubtedly be shining through the prints exhibited at the Snite Museum of Art at the University of Notre Dame.

[Another excellent resource for the study of the TGP in general and the works of artist Leopoldo Méndez in particular, is the book Revolutionary Art and the Mexican Print by Deborah Caplow.]