Josep Renau: Commitment and Culture

The people of Spain have been celebrating the 100th birthday of the Spanish painter, poster designer, and muralist, Josep Renau, through a number of tributes, not the least of which has been a traveling exhibition; Josep Renau (1907-1982): Commitment and Culture. Organized by the Spanish Ministry of Culture and the University of Valencia, Spain, the exhibit is now running at the Universidad de Zaragoza until January 30th, 2009 (View the Spanish language or English translated website). Comprised of over 200 works including photomontage creations, drawings, paintings, and posters, the exhibit spans the artist’s entire influential career.

In 1992 the Museum of Photographic Arts (MoPA) in San Diego, California, presented the very first exhibition in the U.S. of Renau’s magnum opus photomontage series – Fata Morgana USA: The American Way of Life. I attended that exhibit and found it full of acidly sardonic photomontage works that lived up to the title of the series. Unfortunately the MoPA website does not even list the slightest detail concerning its ’92 exhibit. Luckily for all however, the museum website does sell the brilliant catalogue book, Fata Morgana USA: The American Way of Life, which is an indispensable resource regarding the life and art of Renau.

When reading about the early radical proponents of photomontage, rarely is the name of Renau mentioned, yet he played a significant role in the development of the art. His montage works should be regarded with the same sense of appreciation given to the creations of John Heartfield, George Grosz, Alexander Rodchenko, Raul Hausmann, or Hannah Hoch.

The MoPA exhibit of Fata Morgana USA gave us Renau’s view of America as it existed from the Cold War years of the late 1940s to the early ’60s. He depicted a country arrogantly projecting its military power across the globe; a land enthralled by the rise of mass media and hyper-consumerism, embroiled in anticommunist witch-hunts, and terribly divided along racial lines. In fact, some of Renau’s most engaging images had to do with America’s shameful history of racism.

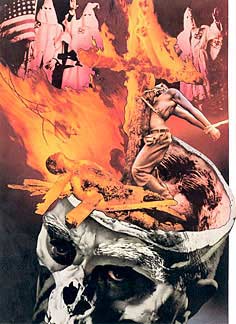

At a time when African Americans could neither vote nor use facilities marked “For Whites Only”, Renau’s images called attention to the fact that democracy in the U.S. was a dream left unfulfilled for millions. Perhaps his most volatile artwork on the subject was the photomontage titled Orgasmo Racial (Racial Orgasm – 1951); which presented a close-up portrait of a skull-faced white man from whose mind sprang the most fearsome imaginings, tortured and murdered black men roasting in fires set by flag waving members of the Ku Klux Klan. No less blistering a condemnation of racism was the artist’s Sombras en la Plantación (Plantation Shadows – 1955); a depiction of a Southern Belle gently swaying to and fro in a tree swing on her estate – the tree casting shadows in which you can see the agonized faces of impoverished Blacks.

To say that Renau is not widely known in the United States would be an understatement. But what is the reason for this unfamiliarity? No doubt his ideology had much to do with it, since he joined the Communist Party of Spain in 1931 and remained a lifelong member until his death. He once said, “I’m not a Communist painter, just a Communist that paints”. A continued ignorance regarding his works, especially for artists at this juncture in history, is nothing short of inexcusable.

Born in Valencia, Spain, Renau graduated from art school in 1925, and then succeeded in making a living as a drawing professor – devoting himself to painting and advertising poster design. He created his first photomontage, The Arctic Man, in 1929. He would be hailed internationally in the years to come for his significant work in developing the art form. When the Spanish Civil War commenced in 1936, he designed posters in support of the Spanish Republic against the insurgent army of General Francisco Franco and his fascist allies Hitler and Mussolini. That same year the Republican government appointed Renau General Director of the Arts, giving him the responsibility of safeguarding Spain’s cultural heritage during the war, and he would transfer part of the Prado Museum’s collection in Madrid to save it from fascist bombardment. In 1937 Renau helped design the Spanish Pavilion at the International Exhibition of Arts and Technology in Paris, France, where he commissioned Pablo Picasso to paint a mural for the Pavilion in support of the Spanish Republic. The result would be Picasso’s Guernica.

When the fascists succeeded in crushing the Spanish Republic in 1939, Renau, like millions of Spaniards, went into exile. He first traveled to France and then to Mexico, where a large number of Republican exiles settled. Upon his arrival in Mexico he began a collaboration with the artist David Alfaro Siqueiros, helping to paint Retrato de la Burguesia (Portrait of the Bourgeoisie), a revolutionary mural for the Electrician’s Union headquarters in Mexico City.

In 1940 Renau became a Mexican citizen, and being well versed in advertising art he made a living designing posters for the Mexican film industry. Eventually he turned his critical gaze toward American culture, and imagined the beginnings of his masterwork, Fata Morgana USA. Those familiar with medieval studies will recognize “Fata Morgana” as the Italian name for Morgan LaFée, King Arthur’s fairy half-sister who produced mirages in order to bewilder enemies. But Renau was interested in the name because it defined a “mirage” as an actual phenomenon, and he had it in mind to use his caustic photomontage art to expose American myths as the greatest of all illusions.

To accomplish his task Renau combined his mastery of photomontage with his expertise in the language of mass media and advertising design; not to conjure up a forerunner to pop art, which was accommodationist to corporate power, but to create a visual language that would subvert advertising and the system it sprang from. Renau began compiling thousands of photographs from the pages of American magazines and newspapers, inventing a catalog system for the collection of images to facilitate the construction of his montages. With precision Renau used the simple tools of razor blade and glue to combine photographic elements, putting the last touches on a montage by painting out unwanted areas or filling in details with pencil or brush. When a finalized work was photographed for publication, the constructed image appeared altogether seamless. Years later the artist would comment on the beginnings of his project, saying that it:

“(….) was to a considerable part drafted in Mexico, the only Latin American country which has a joint border with the United States and where, for this reason, the physical, psychological and political pressure of Yankee imperialism is expressed more directly and brutally than anywhere else.

(….) It is noteworthy how much society in USA is most effectively softened up by the powerful eroding action of the big monopolies and how it has become sensitive to the striking feed-back of the mass media (film, radio, television, newspapers, comics, magazines, etc.). This takes place to such a degree that the formula ‘American way of life’ – partially and tendentiously abstracted from social reality itself – is taking on the shape of a real ‘model’; this concerns a considerable part of the US population which has of necessity formed itself in accordance with the commandments of such an abstraction.”

In 1958 Renau moved to the German Democratic Republic where his work on Fata Morgana USA began in earnest. When Spanish dictator Francisco Franco died in 1975, Renau visited Spain the next year for the first time since his exile, taking the opportunity to exhibit some of his Fata Morgana USA images in several cities. As part of the Venice Biennial of ’76, Renau would show his completed Fata Morgana USA series consisting of 69 images. It was not until ’77 that Renau published 40 select works in book form under the title of Fata Morgana USA. In 1982 Renau died in East Berlin at the age of 75.

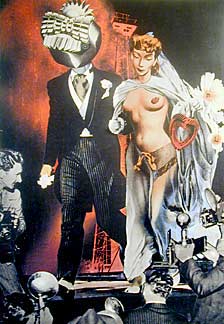

While influenced by dada and surrealism, Renau’s works never offered incoherent rage or dream-like escapism. His was a didactic art that peeled away layers of myth and obfuscation to reveal unpleasant realities. Sometimes his images accomplished this through whimsy, at other times with a frank bluntness, but he always made his point in a highly imaginative way. Take for example his photomontage Recién Casados (Just Married – 1957), depicting a blushing bride, who in actuality is a metaphorical stand-in for the U.S. public. Joined in matrimonial bliss to a robber baron who has an oil drill bit as a head, the bride carries what appears to be a heart shaped floral arrangement, but in reality it is nothing more than another oil drill bit. At the feet of the lovebirds, drooling paparazzi jockey for position, while in the background a gushing oil well symbolizes the couple’s consummated relationship. This rumination on the oligarchy and its relationship to the public was also a prescient comment on gender politics, a topic to which Renau would return time and again.

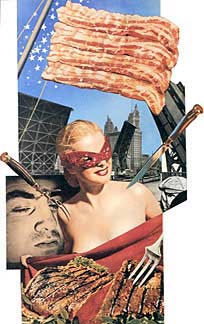

A continually running narrative throughout Fata Morgana USA is the subjugation and objectification of women, which Renau not only attributed to the workings of capitalism, but insisted was necessary for the system to work at all. In Dia de la Victoria (Day of Victory – 1953), Renau constructed his photomontage around a full page photo of an alluring lingerie model posing in Life magazine. At first glance the montage seems festive with its marching band, confetti, streamers and fluttering flags, until one notices the barely concealed caption to the original photo; “Victory Lingerie: A top U.S. designer creates models to welcome home service husbands”. A second glance reveals the scantily clad model is surrounded by U.S. veterans of the Korean War – and they are all amputees.

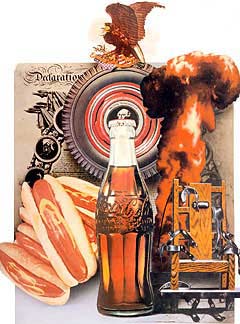

Taken as a whole, Fata Morgana USA can be seen as a comprehensive denunciation of capitalist culture, but of the dozens of images in the series that strike at commercialism, perhaps none cut so deeply as the 1972 photomontage, Sociedad de Consumidor (Consumer Society). Here Renau visualized the citizen being reduced to nothing more than a mindless consumer, ingesting without hesitation an endless stream of manufactured goods and desires that includes the ideology of capitalism itself. But while the word “consumption” denotes the act or process of consuming things, it is also an archaic medical term that refers to the wasting away of the body; and the physical presence of Renau’s consumer has withered into an undemanding and simple receptacle. We are left to wonder how the artist would have commented on the “Black Friday” 2008 Christmas season in the U.S., when hundreds of holiday shoppers in a mad rush to buy cheap consumer goods at a New York Wal-Mart trampled an employee to death.