Making a Killing in Central America

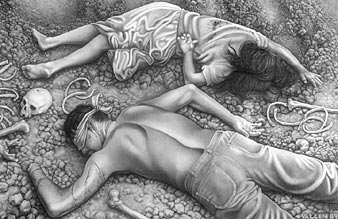

In 1989 I created a pencil drawing titled We’re Making A Killing In Central America. The image depicts two of the many thousands of innocent civilians who were tortured and murdered in Central America during the bloody conflicts of the 1980s. To “make a killing” is an English idiom that means – to do something resulting in substantial financial success – and while hundreds of thousands of Central Americans perished during the counterinsurgency wars of the ’80s, there were those who profited handsomely from the loss of life.

The Refuge Media Project is an organization of filmmakers, health educators, and human rights activists who have been campaigning against state sponsored torture. Project Director Ben Achtenberg asked that I contribute some of my original artworks to the Refuge Media Project website in order to strengthen “the community of those who are trying to find ways, through their own disparate professions and media, to take a stand against torture”. Finding the organization in perfect accordance with my own views regarding regimes that abuse human and civil rights, I have made available to them some of my works – including We’re Making A Killing In Central America. You can view these and other artworks at the Refuge Media Project’s online Image Gallery.

There was an upsurge of extra-judicial killings in Central America during the late 1970s, when government forces and right-wing death squads in Nicaragua, Guatemala, and El Salvador began annihilating opposition groups and individuals by way of kidnapping and assassination. Civilians who were abducted became known as desaparecidos, or “disappeared people”, and once someone was seized they were rarely found alive again. To intimidate populations restive for social change, death squads tortured and murdered their victims, then dumped the mutilated bodies in public places. The killers took to leaving their prey in designated areas that widely became known as “body dumps”. If a relative, friend, or associate was missing, people went to search for them in such places. Untold thousands perished in this way, including union organizers, workers, students, teachers, and peasants.

While most of the victims of this slaughter remain nameless to us, there were high profile cases that stunned North Americans. In 1980 the Archbishop of San Salvador, Óscar Arnulfo Romero, was murdered by a right-wing death squad on March 24, 1980, while celebrating Mass at a small chapel. Unbelievably, even Romero’s funeral, attended by some 250,000 mourners, was attacked by right-wing snipers who killed dozens of people. Some eight months later, three American Roman Catholic nuns and a young missionary were kidnapped, rapped, and shot dead at close range by members of the U.S. backed Salvadoran army – their bodies left in shallow graves.

My drawing was indirectly inspired by the November 16, 1989, murder of six Jesuit priests carried out by the Salvadoran army. The priests, which included the rector and vice rector of El Salvador’s esteemed Central American University, were taken from their beds in an early morning army raid on a home in the capital of San Salvador. They were brutally tortured and then shot in the head. The priest’s housekeeper and her 15-year-old daughter were also viciously murdered by the soldiers.

I was so outraged by this bloody crime that I was moved to create my drawing that same year – the work’s title alluding to U.S. government complicity in arming, training, and financing the very soldiers responsible for slaughtering the innocents. But rather than depicting a well known case, I wanted to memorialize the anonymous masses who had fallen victim to the para-military death squads. In ’89 I self-published my black & white artwork as a flyer which bore the artwork’s title as its headline, and I distributed 5,000 copies of the leaflet across the city of Los Angeles.

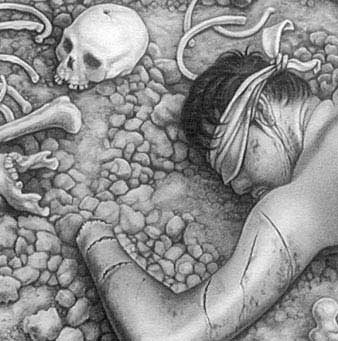

My drawing portrays a slain man and women laying side by side in a body dump, the grisly evidence of previous assassinations surrounding them. The man still wears the blindfold his tormentors tied over his eyes, his body bares knife wounds, his left hand has been chopped off, as has a finger from his right hand. The barefoot woman has a single bullet wound in her back. Were the two – friends, lovers, relatives? Did they know one another at all? Were they student intellectuals or peasant laborers? Were they among the first to die in the beginnings of the ’70s bloodletting, or were they some of the last to perish in the final convulsive acts of violence that took place in the early ’90s? We may never know the names of all the victims of state sponsored torture and murder in Central America – but we can work to assure that justice will at last find their killers.