1930s: The Making of “The New Man”

Those fortunate to see the latest exhibition at the National Gallery of Canada, 1930s: The Making of “The New Man,” will not only have the opportunity to feast their eyes upon some of the greatest artworks of the 20th century – they will be given ample evidence of how artists once responded to calamity and social crisis.

On view until September 7, 2008, the exhibit presents over 200 paintings, sculptures, and photographs from world renowned artists the likes of Pablo Picasso, Wassily Kandinsky, Diego Rivera, David Alfaro Siqueiros, John Heartfield, George Grosz, Thomas Hart Benton, Grant Wood, Alberto Giacometti, Alexander Rodchenko, Walker Evans, Salvador Dalí, Philip Guston, Ivan Le Lorraine Albright, Otto Dix, Henri Matisse, and others too numerous to list here.

I am dubious of the museum’s premise for the exhibition; which stresses how “in the 1930s, biology became a force for change.” In the 1930s those on the left used the metaphorical phrase “a new man” to articulate a belief in the betterment of society and the advancement of humanity, not through eugenics, but by the application of economic policies and scientific progress.

The popular expression was optimistically tied to modernist conceptualizations of communal development and a utopian future. It was the Nazis who twisted the concept of biological determinism into a nightmare of forced sterilizations and mass killings in the pursuit of racial purity. For the National Gallery of Canada to suggest that 1930s modernism on the whole was fixated on biology as “a force for change” is indeed a bizarre stretching of the facts.

My misgivings regarding curatorial approach aside, I feel the National Gallery of Canada has brought together an amazing number of profound works for their “New Man” exhibit, and I would like to comment on two of my favorites. Those with an appetite for more information on the art of the 1930s should purchase the exhibition catalog.

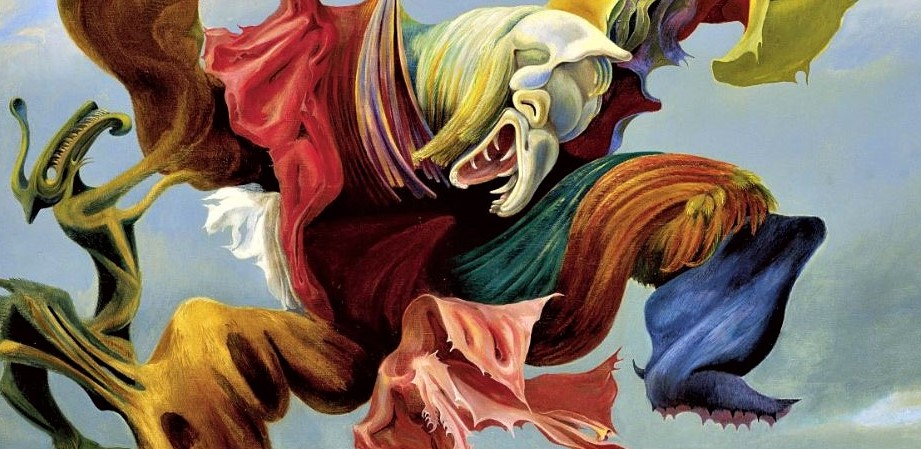

Aficionados of surrealism will be happy to know that L’Ange du Foyer (Fireside Angel), by German painter Max Ernst, is included in the exhibit. Like many German artists of the period, Ernst served four hellish years as a soldier on the battlefields of World War I (1914-1918). Immediately after the war he co-founded the Cologne Dada group, which introduced him to an ever widening circle of radical artists. He left Germany in 1922 to settle in Montparnasse, France, where he joined the Surrealist group founded by André Breton.

While in France he created the masterwork Fireside Angel in 1937. It was not exactly a prescient work, as anyone who was following events closely could see what was becoming of the world. The reign of Hitler had begun in 1933, the Italian fascists under Mussolini invaded Ethiopia in 1936, while General Franco and his fascist movement were in arms against the Spanish Republic. Nevertheless, Ernst’s painting well expressed the gathering menace then engulfing the world.

Fireside Angel is the depiction of an indescribable creature as it storms with rage through a desolate landscape. By referring to his impossible beast as an “angel,” the artist warned that in embracing lofty and exalted ideas we sometimes end up with the devil. It seems we never succeeded in banishing the Fireside Angel Ernst caught a glimpse of, and if we would only pay close attention… we could see the monster riding roughshod over humanity today.

The American surrealist painter, Peter Blume (1906-1992), was once highly regarded as an American figurative painter, though today he is unfortunately almost entirely forgotten. Employing the same techniques utilized by Renaissance artists, Blume’s paintings made use of a near photographic realism, but his narrative works were permeated with surrealist vision and social realist spirit.

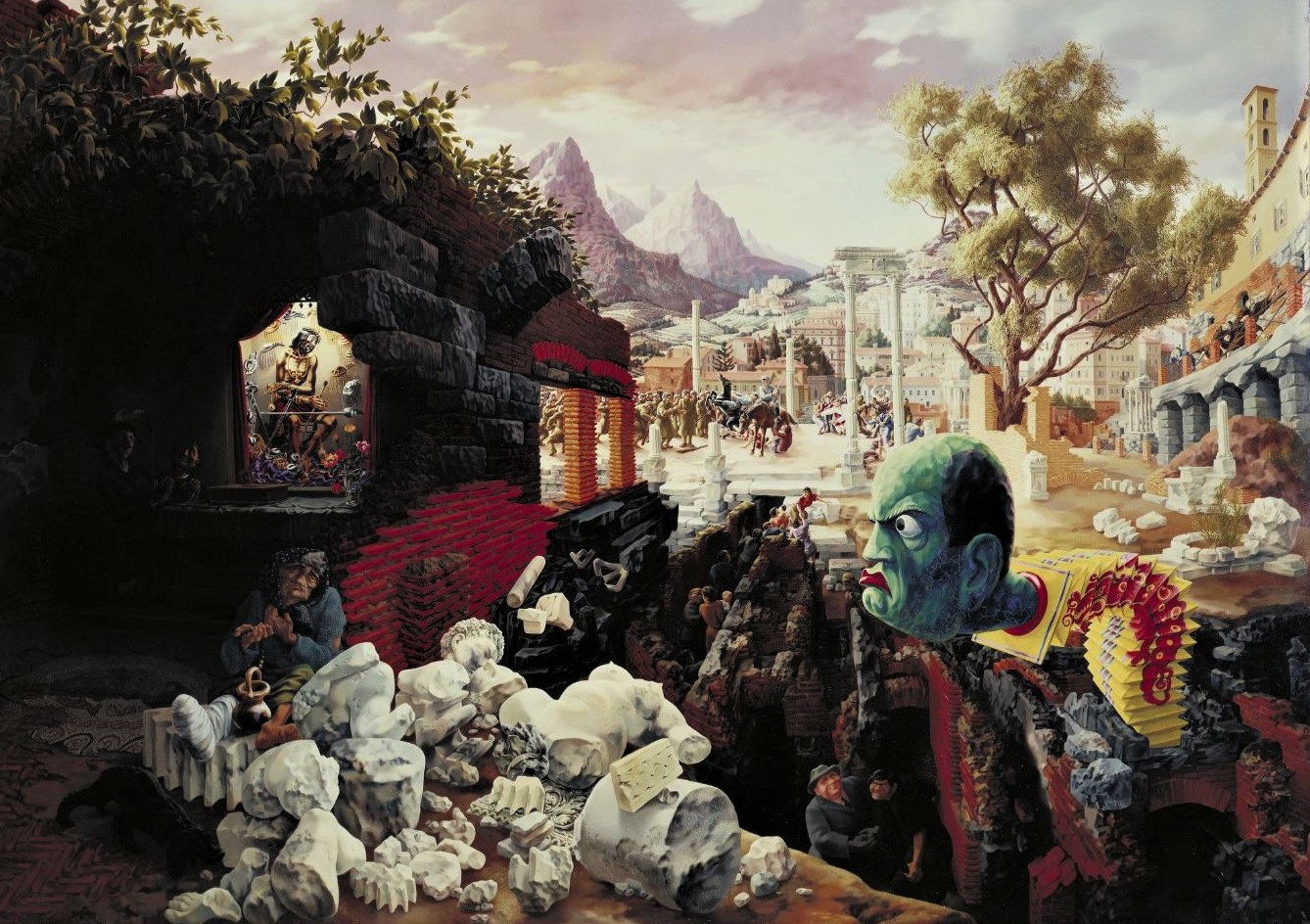

Blume spent 1932 in Rome, Italy, on a Guggenheim grant, the same year the Italian fascist movement celebrated the tenth anniversary of its so-called “March on Rome,” the coup d’état that brought dictator Benito Mussolini and his National Fascist Party to power. After returning to the U.S. Blume brooded over what he had witnessed before starting work in 1934 on The Eternal City, a painting that would take him three years to complete and which is now part of “The New Man” exhibit.

As he was working on the final touches of his painting in 1936, Blume wrote a proclamation against war and fascism titled “The Artist Must Choose“. In his essay he exclaimed; “We, as artists, must take our place in this crisis on the side of growth and civilization against barbarism and reaction, and help to create a better social order.”

Blume used a contemporaneous view of the Roman Forum, the political and religious center of the ancient Empire, as the setting for his picture, but the charming ruins made a farce of the city’s nickname of “The Eternal City.”

In the painting’s distant background Fascist troops can be seen attacking a worker’s demonstration, while in the foreground a number of portentous images vie for our attention.

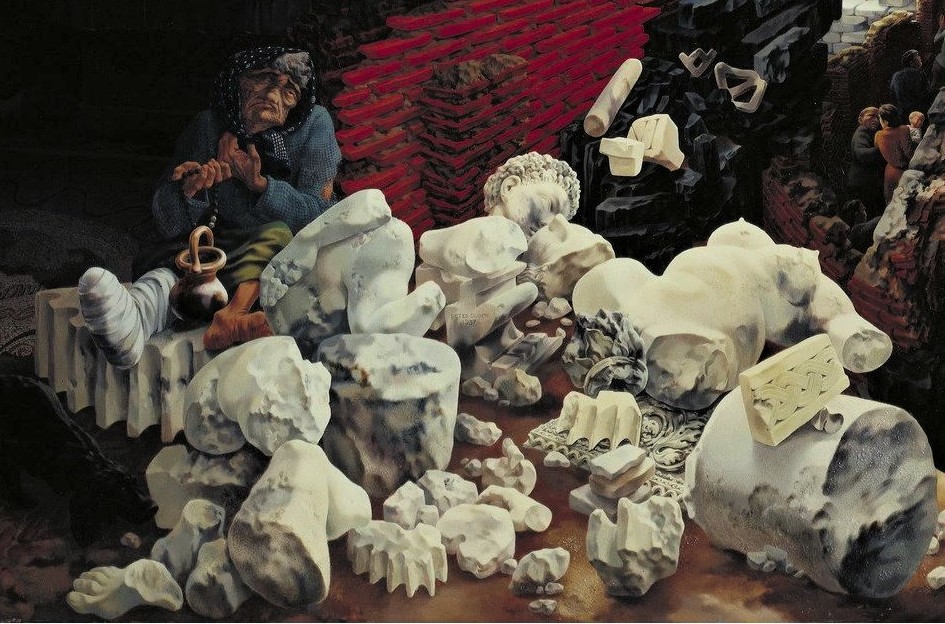

On the left can be seen a polychromed wood statue of Christ situated in a building without a roof, sunrays illuminating the religious figurine mockingly bedecked with military epaulettes and swords. Directly below that tableau a crippled beggar can be seen sitting amongst the broken marble statues and columns of civilization laid low. At right, Mussolini as a gaudy and malevolent jack-in-the-box looms over the entire scene, and lurking in the disintegrating tunnels of the Forum beneath Il Duce’s giant green head, a grinning blackshirt thug and his capitalist paymaster can be seen.

Upon completing The Eternal City in 1937, Blume exhibited the painting at the Julien Levy Gallery in Manhattan. Even though the message of Blume’s anti-fascist work was unambiguous, especially when combined with his written proclamation, numerous critics voiced thickheaded and imperceptive remarks concerning the work.

The New York Sun’s widely read art critic, Henry McBride, made this vinegary comment about Blume and his painting: “He won, it seems, a Guggenheim fellowship, and went to Italy nominally as an art student but actually as a political spy, and returns with a picture that pretends to mock Mussolini. This, of course, is an odd undertaking for an American artist.”

Edward Alden Jewell, art critic for the New York Times wrote: “The political aspects of this treatise are not altogether clear. We are left in doubt as to whether the propagandist considers this modern dictator a self-sprung megalomaniac or a figurehead manipulated by social forces that have taken control of the situation in Italy. Scarcely more convincing is the religious symbol employed. There is nowhere evident the great transfiguring principle itself of Christian love and Christian sacrifice.”

That Edward Alden Jewell referred to Blume as a “propagandist” is revealing, especially since The Eternal City was the only explicitly political painting ever created by Blume. The open hostility that American art critics displayed towards Blume’s painting was but one indication of the growing disfavor to fall upon figurative and social realist artists in the late 1930s, not to mention an indifference towards the rise of fascism.

In a letter to the New York Times in 1943, painters Mark Rothko, Adolph Gottlieb, and Barnett Newman called for an art that would transcend real world issues in favor of pure abstraction. Refuting realism, they declared that meaning in art can only “come out of a consummated experience between picture and onlooker,” further stating that “We want to reassert the picture plane. We are for flat forms, because they destroy illusion and reveal truth.” Abstract Expressionism soon came to dominate American art, and to the detriment of us all, the realism practiced by Peter Blume was declared hopelessly passé by “serious” art critics, collectors, and museums.

Viewers of “The New Man,” will no doubt be left with some gnawing questions regarding the state of contemporary art. After taking in the exhibit and seeing Pablo Picasso’s composition studies for his Guernica mural, Philip Guston’s painting excoriating the air war against civilians during the Spanish Civil War, the acerbic wit displayed in the photomontage works of John Heartfield, and the compassion shown to America’s underclass in the photographs of Walker Evans; the viewer might ask, “Why are we not seeing socially conscious art today?”

I would argue that such works are indeed being created. As to why we are not seeing them, or hearing of them… is another matter entirely.