Edward Biberman Revisited

Edward Biberman was born in Philadelphia in 1904, but left his mark as a California Modernist painter. Now almost forgotten save for aficionados of the California Modernist school, Biberman was the subject of a fascinating 2009 retrospective: Edward Biberman Revisited, held at the Los Angeles Municipal Art Gallery in Barnsdall Park.

While the small Biberman exhibit catalog that accompanied the show rightly described Biberman as an important post war California Modernist artist, and notes his having created paintings of great social import, little was said about the artist’s embrace of social realism or the political controversies that swirled around him. This shortcoming was exacerbated by the layout of the show itself, which presented no coherent timeline for the paintings, but rather presents works from the early 30s and 40s alongside those created in the 70s and 80s. Unfortunately this made it difficult to see how the artist progressed, and especially how he was buffeted by and reacted to, historic events.

Captions for paintings were also short on pertinent details, leaving all but the most stalwart students of history clueless about the subjects depicted in Biberman’s remarkable paintings. Despite these deficiencies, Edward Biberman Revisited was a must see exhibit and I commend the Los Angeles Municipal Art Gallery for presenting it to the public. In this article I will focus on just two of the noteworthy paintings from the show, Biberman’s contemporary Pieta, and the portrait of African American actor, singer, and political radical, Paul Robeson. I will also endeavor to present some of the background information on Mr. Biberman that was unfortunately left out of the exhibit.

In the early 1920s, the 19-year-old Biberman rented a studio in Paris, where he became familiar with exponents of Modernism and their works. Despite the experiments with cubism and abstraction that he witnessed all around him, Biberman would later say that he “quickly decided abstractionism was not for me.” He would not only embrace realism in painting, he would stubbornly continue to adhere to it even as abstract art became ascendant and completely dominant in the art world. From Paris he moved to Berlin, but felt uneasy with the rightward drift he witnessed in German society. He described his Berlin neighborhood as a “Nazi nest” and pulled up stakes for America, where he acquired a studio on 57th Street in New York. He did well, painting portraits of individuals like Martha Graham and Joan Crawford, but then came the stock market crash in 1929 and Edward’s father, a businessman ruined by the crash – committed suicide.

At this point Edward Biberman became committed to using his art in addressing the world’s injustices. He started to paint workers, the unemployed, and the disenfranchised. He respected the Mexican Muralist Movement to the highest degree, having met Rivera, Siqueiros, and Orozco while in New York. In 1935 Biberman decided to move to California, and so drove across country, stopping in New Mexico where he painted alongside Georgia O’Keefe before continuing to Los Angeles.

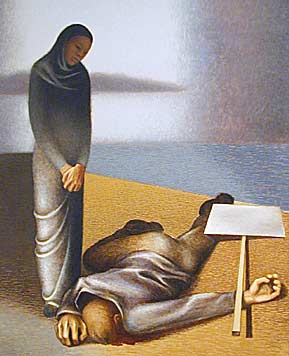

In 1939 Biberman painted his Pieta, a masterpiece that has as much relevance today as when the artist first painted it. There is no doubt that the work was inspired by his exposure to Mexico’s radical social realists, but one can also assume that what he discovered in Los Angeles, a segregated city where Chicanos and Mexican immigrants formed a permanent underclass, also contributed to the creation of the painting.

Though Pieta depicts what appears to be a Mexican Indian woman mourning over the body of a slain worker, the painting has a universal and timeless quality to it.

The murdered worker lies face down on the ground in an ungainly position, his placard flung to one side as his blood coagulates around his head. The backdrop is an endless space where land, sea, and sky meet, lending a sense of the surreal to the scene. An up close examination of the painting reveals a masterly application of paint, with Biberman having built up layers of transparent colors to great effect. His gloppy brush strokes of golden ochre paint perfectly replicate a parched and unforgiving earth. Pieta is as good a work of social realism as I have ever seen produced by anyone, anywhere, and it should be known by all.

While in his new home city of L.A. Biberman met actress and artist Sonja Dahl at a meeting of the Hollywood Anti-Nazi League, an anti-fascist organization that helped German émigrés settle in the U.S. (the league helped famed author Thomas Mann settle in L.A.) Biberman and Dahl fell in love and married as WWII was approaching, moving into a modest home located just below the famous Hollywood sign.

Edward’s brother, Herbert J. Biberman, arrived in Hollywood to pursue work as a director, screenwriter and producer of films. Herbert also became active in the Anti-Nazi League, and Sonja Dahl-Biberman later recalled that at the time, anyone who was anti-Nazi was suspected of being a communist. When the war ultimately broke out, Edward served as a corporal in the state guard, and Sonja joined the Women’s Ambulance and Defense Guard. The war lasted four-and-a-half years, and with the defeat of fascism the Biberman’s and their friends felt they had won a great collective victory—but then came the Cold War, the House Un-American Activities Committee (HUAC) and the anti-communist hysteria that came to be known as McCarthyism. In her December 2003 article for the Los Angeles Times Magazine, A Place in the Sun, Catching Up with Edward Biberman’s Los Angeles, Emily Young wrote:

“Though his portraits of Lena Horne and Dashiell Hammett are in the Smithsonian’s National Portrait Gallery, the left-leaning Biberman initially devoted more of his energy to depicting Depression-era bread lines, the struggles of organized labor and the Communist witch hunt in Hollywood that undercut his career. (….) Biberman remained popular until social realism, a style he used for his politically charged paintings, fell out of favor. When his brother was branded a member of the Hollywood Ten, he suffered further from guilt by association. Still, Biberman continued to paint, teach and write, developing a pre-Hockney Los Angeles aesthetic that would influence the art world’s next generation.”

While Ms. Young’s recollection of Biberman’s early work is technically accurate, she fails to convey to the reader the noxious atmosphere of political repression Biberman was laboring under, or exactly why social realism “fell out of favor.” Lena Horne, the great African American singer and actress, and Dashiell Hammett, author of detective stories like The Thin Man and The Maltese Falcon, were both named as communists at HUAC hearings and found themselves blacklisted. In 1947 Ms. Horne was marked as a “communist sympathizer” for her civil rights activism and friendship with Paul Robeson, and was thus unable to perform on television, radio or in the movies until the late 1950s.

Political repression came home for Edward Biberman in a profoundly personal way when he was identified as a communist by a “friendly witness” to HUAC because he had helped to organize an Artist’s Union within the WPA project. His beloved wife Sonja was also identified as a communist by a “friendly witness” to HUAC. Then his brother Herbert was accused in 1947 of participating in “communist activities” by HUAC, along with nine other Hollywood professionals who became known as the Hollywood Ten.

At the HUAC hearings Herbert took the 5th amendment, refusing to name “fellow communists” or to confirm or deny the allegations made against him. In 1950 he would be sentenced to six months in prison and barred from working in Hollywood. Even though he had little money Edward worked tirelessly to get his brother out on parole and help pay his legal fees, actions which made him suspect in the eyes of the government. Dashiell Hammett would later be found guilty of contempt of Congress for refusing to name communist associates and was sent to prison for six months in 1951.

One of Biberman’s paintings in the Municipal Art Gallery exhibit is titled, Conspiracy. It depicts a group of white men in suits, huddled before a bank of microphones. Painted as a simple agitated line drawing in burnt umber filled in with a limited palette of mute earth colors, the image suggests a plot of some sort. The gallery provides absolutely no information as to what the painting gives a picture of, but it is not had to see that the oil on masonite painting is a direct reference to the HUAC witch trials and the persecution of Mr. Biberman, his wife, brother, and their professional associates.

In his celebrated biography Paul Robeson, author Martin Bauml Duberman described the political atmosphere in the U.S. at the time of Robeson having his portrait painted by Biberman in Los Angeles. Duberman specifically writes about a live performance Robeson gave at a 1949 NAACP Youth Council Rally in Los Angeles. It should be noted that just prior to his L.A. appearance, Robeson had given an August, ’49 performance in Peekskill, New York, where a huge violent mob motivated by racial hatred and anticommunism had almost succeeded in killing the black singer:

“The (Los Angeles) City Council dubbed Robeson’s coming concert an ‘invasion’ and unanimously passed a resolution urging a boycott. One councilman, Lloyd C. Davies, went out of his way to ‘applaud and commend those in Peekskill who had the courage to get out there and do what they did to show up Robeson for what he is. I’d be inclined to be down there throwing rocks myself.’ An FBI agent reported to J. Edgar Hoover that ‘the Communist Party logically might endeavor to foment an incident at the concert in order to arouse the crowd.’

Hollywood gossip columnists Louella Parsons and Jimmy Fidler fanned the flames with rumors of violence, and the Motion Picture Alliance for the Preservation of American Ideals published ads red-baiting Robeson. Charlotta Bass, publisher of the California Eagle, the black newspaper that sponsored Robeson’s Los Angles appearance, was swamped with threatening phone calls and denied insurance coverage.

Robeson’s supporters fought back. The Los Angeles NAACP Youth Council passed a resolution calling on all young people, black and white, to attend the concert. The prestigious national black fraternity (Robeson’s own), Alpha Phi Alpha, announced that it would host a luncheon in his honor the day following the concert. His supporters deluged the City Council with angry protests over its call for a boycott, and they turned out in force for the event itself. A tiny group of race-baiters did go to hear a local realtor call for the expulsion of all blacks and Jews from Los Angeles – but fifteen thousand went to hear Robeson, and the rally came off without incident.

A special force of black police officers (among them future Mayor Thomas Bradley) was assigned to protect Robeson. He thanked them from the podium and asked that the L.A. police protect ‘every colored boy, every Mexican-American boy, every white boy on the streets of Los Angeles.’ He thanked the Jewish people of Peekskill for having turned out in numbers to protect him in that town. And he thanked the crowd in front of him for having turned out to defend its own liberties. He would continue, he said, ‘to speak up militantly for the rights of my people’; he told the rally that when asked the question ‘Paul, what’s happened to you?’ he replied, ‘Nothing’s happened to me. I’m just looking for freedom.’ Then he sang ‘We Shall Not Be Moved,’ and the last verse, ‘Black and white together, we shall not be moved’ brought the crowd to its feet.”

In an interview with Biberman conducted in 1977 for the UCLA Special Collections, Biberman described Robeson sitting for his portrait; “We were never alone. He would always make several appointments here for the time that he was posing. Earl Robinson (who accompanied Robeson on piano during performances) would be sitting at this piano banging away a new tune that he wanted Paul to hear, and somebody would be reading a script, and somebody else would be interviewing him.”

Biberman’s portrait of Paul Robeson was a focal point of the exhibit at the Municipal Art Gallery, and it was an imposing work indeed, conveying all of the pride, determination, and dogged tenacity of the internationally famous singer. But aside from being an impressive painting of a formidable character, it is also confirmation of Biberman’s own valor, for it took no small amount of courage to stand up to HUAC and create a sympathetic portrait of Robeson during such trying times.

For those unable to attend the Los Angeles Municipal Art Gallery exhibition, a gallery of artworks by Edward Biberman can be seen here. Also, a fascinating interview was conducted with Biberman on April 15, 1964, for the Archives of American Art of the Smithsonian Institution. The interviewer asked Biberman for his evaluation of the WPA Federal Arts Project, and the artist’s timely answer has great resonance in the present:

“Well, of course I have a very partisan attitude to this whole matter. I am unequivocally in favor of it. I think it was one of the brightest spots in the history of American art, and I hope that we will see a revival of a government program. I fervently hope it will not be necessitated by another depression, which of course is what started the WPA project. That was a relief measure primarily, not a cultural measure.

But irrespective of what brought it into being, and irrespective of the arguments against any government art program, and I think I’m familiar with all of the “anti” arguments, I find that this was an enormously productive period in American art. I think it actually brought into being and furthered the careers of many painters. The names of these artists are legion.”

Edward Biberman Revisited ran at the Los Angeles Municipal Art Gallery, Barnsdall Park in April of 2009. The Gallery is located at 4800 Hollywood Blvd, Los Angeles, CA 90027. On March 6, 2009 the Los Angeles Municipal Art Gallery Associates (LAMAGA) screened Jeff Kaufman’s 2006 documentary, Brush with Life: the Art of Being Edward Biberman. The film was followed by a talk with Jeff Kaufman, the film’s director, and Suzanne W. Zada, curator of Edward Biberman Revisited.