A New Look at Rivera’s “Gloriosa Victoria.”

I published an article on Oct. 5, 2007 titled Diego Rivera: Glorious Victory! It was about the Diego Rivera retrospective then on view at the Palacio de Bellas Artes (Palace of Fine Arts) in Mexico City, Mexico. The real treasure in that show was the artist’s 1954 mural, Gloriosa Victoria (Glorious Victory).

Gloriosa Victoria is a large oil on linen “mobile mural” that had been touring Eastern Europe in 1956 when it somehow became lost. It was discovered rolled up and sitting in a store room at the Pushkin State Museum of Fine Arts in Moscow, Russia in 2006; Rivera had apparently gifted the mural to the Soviet Union. By special arrangement it was loaned to Mexico by the Russian government for the 2007 Palace of Fine Arts exhibition (click here for a larger view of the mural). A number of developments regarding the mural have since led me to write a fresh perspective on its history.

Gloriosa Victoria depicts the 1954 US government engineered coup d’état against the elected government of Guatemala. The mural’s narrative quality is as powerful as a renaissance altarpiece; its recounting of historic events augmented by a superlative handling of composition, color, and form. There are no subtleties or abstractions in Rivera’s telling of this bleak chapter in human events; he offers no tales of universal suffering or “the human condition.” He strips away the mythic to reveal the common truths found in the chronicles of Latin America.

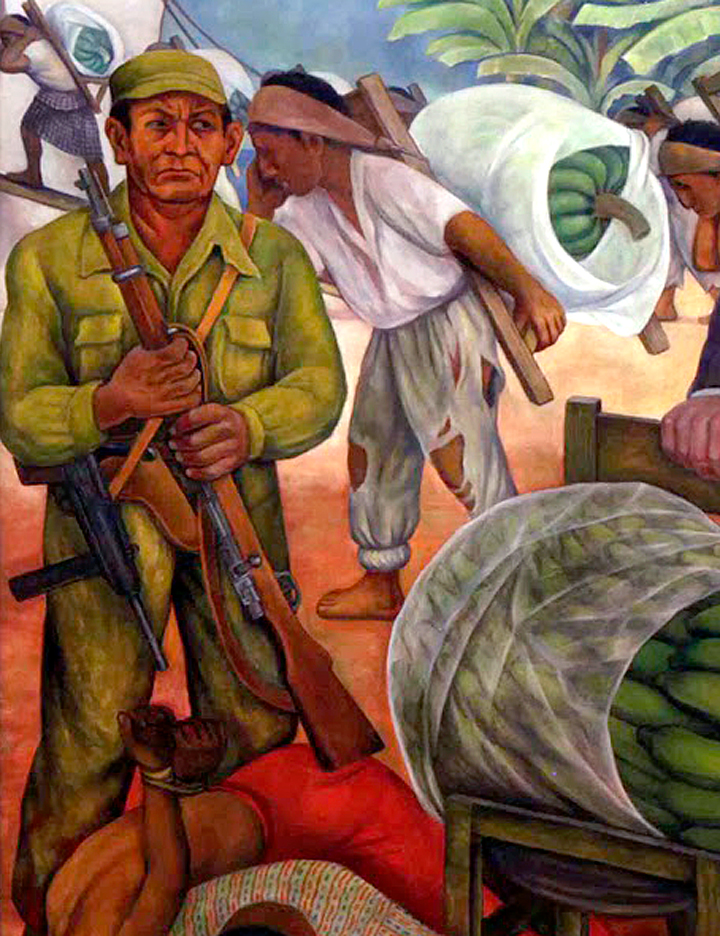

In the above detail from the mural, the man at left dressed in khaki fatigues is the US Secretary of State, John Foster Dulles. He clutches a bomb that bears the face of US President, Dwight D. Eisenhower. The man in the dark suit seen whispering into the ear of John Foster Dulles is his brother Allen Dulles, Director of the Central Intelligence Agency. The CIA chief wears a messenger bag stuffed with Yankee dollars, and he is passing that money to John Peurifoy, the man behind and to the right of the Secretary of State. Peurifoy is handing out the cash to the traitorous military officers and their goons who overthrew the elected government of Jacobo Árbenz by force of arms.

Standing front and center before this group of coup plotters is Air Force Colonel, Carlos Castillo Armas. The breast pocket of his “Eisenhower jacket” is full of American dollars; he carries a Colt Model 1911 .45 ACP pistol in his waist band. Armas, the leader of the CIA backed “rebels,” successfully ousted the government of Árbenz and was named head of the military junta. Weeks later a faux election was held in which Armas won 99.9% of the vote. Along the bottom half of the painting are the bloody, mutilated, bullet-riddled bodies of Guatemalans killed in the coup.

The tall man in black blessing the scene deserves special mention, in Rivera’s overall composition the viewer’s eye naturally travels to him. He is Rivera’s depiction of Guatemala’s arch-conservative Catholic Archbishop, Mariano Rossell Arellano (1909-1983). In the opening days of the coup the CIA distributed leaflets across Guatemala that exhorted the population to support the putsch. One such flyer was a pastoral letter issued under the Archbishop’s name, it read in part:

“The people of Guatemala must rise as one man against this enemy. Our struggle against Communism must be… a crusade of prayer and sacrifice, as well as intensive spreading of the social doctrine of the church and a total rejection of Communist propaganda – for the love of God and Guatemala.”

The pastoral letter was not written by Archbishop Arellano. Though its content was approved by the Archbishop, the letter was actually composed by CIA officials in coordination with conservative Catholic clergy in the United States [1]. Rivera named his painting after a remark made by Secretary of State Dulles, who immediately after the US successfully overthrew the government of Guatemala, proclaimed the act to be a “glorious victory for democracy.”

One final note about Rivera’s painting; when it was rediscovered at the Pushkin and examined, a second painting was discovered on the backside of Glorious Victory. It was an unfinished portrait that Rivera started but never finished; it was titled “Portrait of a leader of the Mexican Communist Party, Dionisio Encinas.”

Nearly two months after I published my Glorious Victory! article, the New York Times published a rather disparaging review of the Rivera retrospective that was written by Elisabeth Malkin. Titled Rivera, Fridamania’s Other Half, Gets His Due, it offered the following appraisal:

“The centerpiece of the show was ‘Glorious Victory,’ a mural Rivera painted at the end of his life, after the American-backed coup that brought down the democratically elected government of Guatemala in 1954. It is pure propaganda, almost caricature…”

As George Orwell once wrote, “all art is propaganda.” I could argue that the contemporary art the NYT tirelessly writes about also falls under that description, but that’s another essay. Malkin’s assertion that Rivera’s Glorious Victory is nothing but “pure propaganda,” precludes a discussion regarding the aesthetics of social realism, preferring instead mockery and contempt in lieu of serious criticism. She recounts the historic fact that an “American-backed coup” destroyed “the democratically elected government of Guatemala in 1954,” but then condemns Rivera’s artistic depiction of that same reality as “pure propaganda.” How would Malkin like an artist to depict the nettlesome subject in a work of art? My guess would be… not at all.

Nevertheless, there is some truth in Malkin’s remark. Rivera continually jumped back and forth from social realism—a genre focused on the human condition and realities of everyday life, to “socialist realism,” the Stalinist view that art must serve the needs of the worker’s revolution.

After Glorious Victory was seen by thousands at the Palacio de Bellas Artes retrospective, the mural was moved to the Museo Dolores Olmedo in Mexico City. It was displayed there from January through June 2008 before being returned to the Pushkin collection. The Russian government loaned Glorious Victory to Guatemala in 2010, where it was shown at the National Palace of Culture as part of that museum’s ambitious art exhibition, ¡Oh Revolución! 1944-2010: Múltiples visiones (Oh Revolution! 1944-2010: Multiple Visions). That exhibit was proclaimed by Guatemalan officials as the most important art show mounted in the country in six decades.

President Álvaro Colom provided remarks for the Oct 1, 2010 opening ceremonies of ¡Oh Revolución!, but before I comment further, allow me to guide you through some of Guatemala’s recent political history, which makes the showing of Rivera’s mural in Guatemala that much more profound.

In 2003 Colom ran for president as the candidate of the social-democratic National Unity of Hope party. He lost to the oligarch Óscar Berger, who ran as the candidate of the rightist Grand National Alliance party. In 2007 Colom again ran for president on the National Unity of Hope ticket, this time against Otto Pérez Molina and the rightist party he founded, the Patriotic Party. Molina was a retired Army General, trained at the US School of the Americas, who had close ties to the military regimes that ran Guatemala in the early 1980s. He lost the election to Colom, who became the only “left” leaning politician to be elected president in 53 years; the first of course was the ill-fated Árbenz, who was overthrown in the U.S. organized coup d’état.

As previously noted, President Colom led the opening ceremonies of the ¡Oh Revolución! exhibit, which presented Guatemalan history through paintings, drawings, and prints, from the overthrow of Árbenz to the current period. The pièce de résistance in the show was of course Rivera’s Gloriosa Victoria, and President Colom thanked the Russian government for loaning it to his nation. At the time of the exhibit Guatemala was celebrating the anniversary of its Diez años de Primavera (Ten Years of Spring), the period between the people’s 1944 overthrow of dictator Jorge Ubico, and the end of the democracy movement brought about by the 1954 US coup against Árbenz.

While President Colom implemented modest reforms during his term in office (2008- 2012), his most significant act was the Oct. 20, 2011 official apology he made for the government’s role in helping to organize the 1954 coup that crushed democracy. Directing his apology to the family of Jacobo Árbenz and to the people of Guatemala, Colom made the apology at the National Palace, saying of the coup; “That day changed Guatemala and we have not recuperated from it yet. It was a crime to Guatemalan society and it was an act of aggression to a government starting its democratic spring.”

President Colom introduced another special guest at the ¡Oh Revolución! opening, Rina Lazo, the Guatemalan-Mexican painter and muralist.

Lazo assisted Diego Rivera from 1947 to 1957, directly helping him paint a number of his most well known mural works. As a young student she won a scholarship to study art in Mexico, and three months after arriving in Mexico City she met Rivera and became his pupil.

Rivera made her a leading assistant, referring to her as his “right hand,” and asked her in 1947 to help him paint the mural Dream of a Sunday Afternoon in the Alameda Central, then being created in the Hotel del Prado (now the Museo Mural Diego Rivera).

In 1954 Lazo assisted Rivera in painting Glorious Victory. One late afternoon while working on the mural, Rivera asked Lazo if she would like to be included in the painting as a background figure. She agreed to pose, and Rivera told her to bring a red blouse to the studio the next day.

The following morning Rivera provided Lazo with a 9mm carbine, set her in an appropriate pose, and began painting.

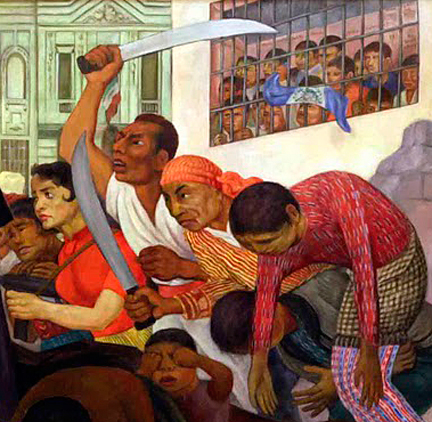

In the upper right corner of Glorious Victory a group of armed workers and compesinos take action to defend their elected government from the coup-makers; two agricultural workers brandish machetes while Rina Lazo in her red blouse wields a carbine.

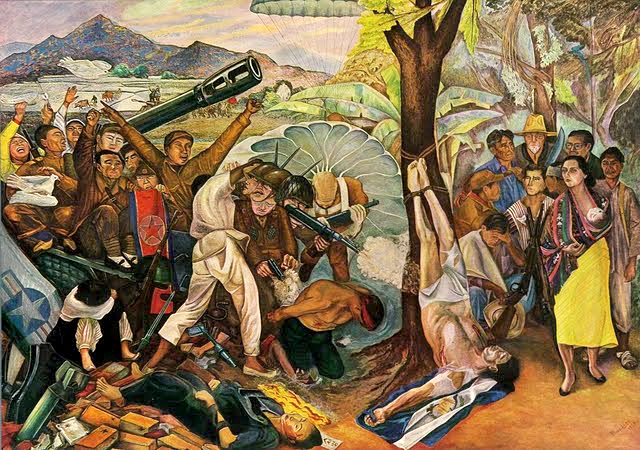

While Rivera was painting Glorious Victory, Lazo was creating her own large canvas titled Venceremos (We Will Win). It linked the US coup in Guatemala with the US war in Korea, which had just concluded with an armistice in 1953. The canvas presented an apocalyptic landscape of Guatemalan jungle and Korean rice paddies, where marauding soldiers massacred Korean and Guatemalan peasants alike.

Of course Diego Rivera and Rina Lazo made absolutely no mention of the Chinese Communist Party invading North Korea with 300,000 soldiers; the CCP assisted North Korea’s communist dictator Kim Il Sung in pushing UN and US soldiers into retreat and seizing Seoul, South Korea. The Communists of China and Soviet Russia both backed Kim Il Sung—in fact the Soviets installed Kim as First Secretary of the Korean Communist Party in 1945. It was the brutal Soviet dictator Joseph Stalin that literally built Kim’s “Korean People’s Army” with modern rifles, tanks, artillery, and attack aircraft. In essence, Rivera and Lazo served as apologists for communist depredation.

In the tableau one unfortunate man shot full of bullet holes is tied upside down to a tree, recalling the Apostle Peter crucified upside down by soldiers of the Roman Empire. Venceremos was also included in ¡Oh Revolución!, and today it is in the collection of the Museo de Bellas Artes de Toluca, México.

Through Diego Rivera and Frida Kahlo, Lazo met Arturo García Bustos, her husband to be. Bustos was one of “Los Fridos,” a small circle of young artists who were not only fiercely loyal students of Kahlo, but lived and worked with Rivera and Kahlo for close to ten years.

Bustos was also a founding member of the Taller de Gráfica Popular (TGP – Popular Graphic Arts Workshop). Lazo and Bustos married in 1949. At the time of this writing Lazo is 93-years old and Bustos is 90; they continue to live together in Mexico City.

By reason of the malaise and torpor of today’s postmodern art, Lazo and Bustos insist that socialist realism – as exemplified by Rivera’s Glorious Victory – will one day make a comeback; as an artist infinitely inspired by Mexican Muralism, I could have shared the assessment of Lazo and Bustos—if they had only preferred social realism over “socialist realism.”

— // —

REFERENCES:

[1] Spiritual Weapons: The Cold War and the Forging of an American National Religion. T. Jeremy Gunn. Publisher: ABC-CLIO, 2008.

View the flickr page created by the Government of Guatemala, celebrating the 2010 exhibition of Gloriosa Victoria at Guatemala’s National Palace of Culture. The photos at the end of the page feature images of President Álvaro Colom, as well as Rina Lazo and her husband Arturo García Bustos.

ADDENDUM:

There is more to this Guatemalan tale. When President Colom’s term in office ended in 2012, his old rival, the former Army General Otto Pérez Molina became the next elected president; despite accusations of corruption and human rights abuses. Three years into his reign the rightist strongman was exposed for involvement in a major corruption scheme. The scam involved the country’s custom service taking bribes from importers in exchange for illegally reducing custom tarifs; the profits of course going to Molina and members of his administration.

Known as La Linea (The Line), the scam was named after the telephone line importers used to arrange bribes with corrupt officials. Hearing of this outrage the people held mass protests for months, filling the streets with demonstrations, conducting strikes, as well as seizing workplaces and schools. Of the 15 million people who live in Guatemala, over 50% of them live in dire poverty. The protests brought the country to a standstill. President Molina, his Vice President Roxana Baldetti, and dozens of officials from their administration, resigned in disgrace and were arrested. Molina and Baldetti are currently in prison and on trial for corruption.

As if things could not get any worse… or more surreal, in October 2015 a former TV comedian named Jimmy Morales was elected president of Guatemala; Morales was inaugurated on January 14, 2016. With no political experience whatsoever, Morales was elected in the wake of the anti-corruption protests that swept General Molina and his cronies from power. Morales ran as the candidate of the right-wing National Convergence Front, founded in 2008 by retired army officers who played a bloody role in the country’s 1960-1996 genocidal civil war. Already, fifteen colleagues of Morales, mostly members of the National Convergence Front, have been arrested for human rights violations related to the war. By the way, attending the inauguration of Jimmy was none other than US Vice-President Joe Biden. Guatemala’s anguish and despair continues… Glorious Victory indeed.