Philip Guston: “I wanted to tell stories.”

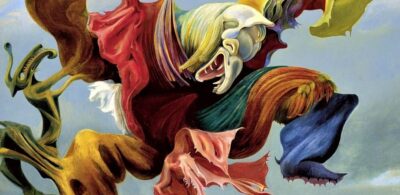

Enigma Variations: Philip Guston and Giorgio de Chirico, is a wonderful survey of paintings by these two promethean artists showing at The Santa Monica Museum of Art until November 25th, 2006. The twenty-six canvases on display reveal the far reaching influence the European Surrealist de Chirico had upon Guston, presenting works from both artists that trace the startling development of their careers over the decades.

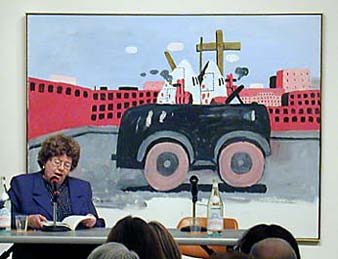

During the evening of Oct 3rd, 2006, I attended Remembering Guston, a special event at the Santa Monica Museum of Art attended by some 80 individuals. Guston’s daughter, Musa Mayer, read from her book Night Studio: A Memoir of Philip Guston.

Mayer’s compelling personal insights into her father’s life held the audience in sway, and cemented my affection for the eccentric artist.

She touched upon many aspects of her father’s professional career; his ardor for the works of the old masters, his driven nature to create, which kept him working in the studio until late at night (hence the title of Mayer’s book), the torment he felt when former admirers attacked him for “betraying” pure abstraction, and the disillusionment suffered over the treatment he received at the hands of a capricious art establishment.

It may come as a surprise to some that I’m an admirer of Guston, who for a while was a leading light in the extreme “non-objective” abstract movement of the early 1950s, but then, he was so many things, and if people delved into his life and works they just might come to share my fascination.

Many accounts have been written about the life and art of Philip Guston, so rather than repeating well known facts, I’d like to make a few personal comments regarding his work, and make a stab at contributing new information about what he accomplished in Los Angeles, city of my birth.

A few of the artist’s statements might make clear my admiration for him. When he was at the height of his fame as a pure abstract painter in 1958, he said, “I do not see why the loss of faith in the known image or symbol should be celebrated as a freedom. It is this loss we suffer, this pathos that motivates modern painting and poetry at its heart.”

In a 1970 interview, he revealed what was behind his leap from pure abstraction to figuration, “I got sick and tired of all that Purity! I wanted to tell stories.” And in a 1974 interview he said, “When the 1960’s came along I was feeling split, schizophrenic. The war, what was happening to America, the brutality of the world. What kind of man was I, sitting at home, reading magazines, going into a frustrated fury about everything, and then going into my studio to adjust a red to a blue?”

Considering the state of the world, these are all ideas contemporary artists should be mulling over.

While most think of Guston as a New York artist, he began his career in Los Angeles, which of course I find endlessly fascinating as an Angelino. It all began in 1919 when the Goldstein family moved to LA from Montreal, Canada, which means Philip (who changed his last name to Guston in 1936), lived in LA from the time he was six years old until he was twenty-three-years old, making him an honorary Angelino in my book.

He started drawing profusely at around thirteen, and upon entering Manual Arts High School in downtown LA, made friends with another young student deeply interested in art, Jackson Pollock. Guston received a Scholarship to Otis Art Institute in 1930, but became disillusioned and left after three months. That same year he befriended Reuben Kadish, who was himself to become a great painter. This is where the story begins to take on mythic proportions, and for an LA artist like myself, the confluence of historic actors and events that played out in my city is almost overwhelming, especially since my interest in these histories shaped my life as an artist.

Guston, Kadish, and the painter Herman Cherry, began attending meetings organized by the left-wing John Reed Club (named after the American journalist and revolutionary), in fact it was Cherry who gave Guston his first exhibit at Hollywood’s Stanley Rose bookshop and gallery in 1931. The John Reed Club met at a number of venues across the city, including the Plaza Art Center in the Italian Hall on LA’s famous Olvera Street.

David Alfaro Siqueiros arrived in LA in April, 1932, and addressed a meeting of the John Reed Club in Hollywood, presenting his approach to art in a paper he titled The Vehicles of Dialectic-Subversive Painting. I’m not certain if Guston attended, but the influence exerted upon him by Siqueiros and the Mexican Muralists was no doubt considerable. When José Clemente Orozco began painting his Prometheus mural at Pomona College, Guston and Jackson Pollock were there to watch.

Millard Sheets, a teacher at the Chouinard Art Institute at the time, invited Siqueiros to paint a mural at the institute, where the Mexican master formed a team of over twenty assistants he called the Bloc of Mural Painters. Philip Guston was a Bloc member, along with Rubin Kadish, Harold Lehman, Fletcher Martin, Murray Hantman, Luis Arenal, Barse Miller, Phil Paradise, Paul Sample (President of the California Arts Club), and others.

Various members of the Bloc helped Siqueiros create three murals in LA, América Tropical (atop the Italian Hall at Olvera Street), Worker’s Meeting (at Chouinard), and Portrait of Mexico Today (at the Pacific Palisades home of film director, Dudley Murphy). Since he was a Bloc member, it’s difficult to imagine Guston not assisting Siqueiros in painting any of the three murals, but I’ve yet to see him credited as a direct assistant. However, he was certainly on that Olvera Street rooftop along with Pollock, listening to Siqueiros talk while working on América Tropical.

In Nov. 1932, the US government deported Siqueiros because of his leftist politics, but the Bloc of Mural Painters continued to be productive. It was around this time that the chief of the LAPD, James E. Davis, established a “Red Squad” to attack Communists and smash up their organizations. Interestingly enough, every biography of Philip Guston that I’ve seen has overlooked, down played, or ignored what I’m about to bring to light, that his first public mural was most likely destroyed by the Los Angeles Police Department Red Squad. The few sources that do mention this little known event fail to present an illustration of the painting, damaged or not.

Soon after the forced departure of Siqueiros the Bloc of Mural Painters organized an exhibit in opposition to racism, the exhibition was sponsored by the John Reed Club of Hollywood. Six members of the Bloc each created two large portable mural panels for the exhibit, and Guston was one of the artists; he chose the trial of the Scottsboro Boys as his theme.

The available information on the exhibit is sparse and conflicting. There’s a chilling account provided by participating Bloc artist, Harold Lehman, stating the show was “scheduled to open in the Barnsdale in Los Angeles in December, 1932,” and that the LAPD attacked the John Reed Club’s headquarters in Hollywood where the artworks were stored, destroying them all so “the controversial images would never reach the light of day.”

Philip Stein, the American artist who painted murals with Siqueiros in Mexico for ten years, and later wrote the biography, Siqueiros: His Life and Works, also mentioned the incident, stating that the Red Squad had “confiscated the paintings, all rich with political content. When eventually the paintings were returned, they were full of bullet holes.”

Robert Storr’s biography on Guston erroneously placed the incident as having occurred one year earlier, and recounted the story in the following manner; “By 1931 Guston had executed his first public work, a series of portable panels based on the notorious racist trial of the Scottsboro Boys. He then watched in anger and amazement as the panels were mutilated by members of the Police “Red Squad” and a gang of American Legionnaires, who took pleasure in using the eyes and genitals of the black figures in the painting for target practice. The persecution that Guston had only imagined thus became all too terrifyingly real.”

The only other account I’ve found so far came from Jean Bruce Poole and Tevvy Ball, in their authoritative history, El Pueblo: The Historic Heart of Los Angeles. The entry in that book states; “Early in 1933 the LAPD Red Squad raided the club offices, and a number of paintings and frescoes were damaged. The club brought suit against the city, claiming that these were valuable works fashioned by Siqueiros’ students and alleging that officers had removed a number of paintings and shot or poked them full of holes.”

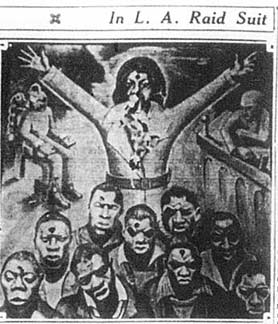

The pieces of the puzzle all fell into place for me when I viewed a reproduction of the July 15th, 1933 edition of the Los Angeles Evening Herald and Express, an LA paper that ceased publication in 1950. The newspaper printed a short article, Club Raid Told by Man Behind Curtain, detailing the police assault on the John Reed Club in Hollywood and the subsequent trial over the damaged art.

The opening paragraph of the article read; “How Harry Buchanan hid behind a curtain in the John Reed Club and witnessed the details of a raid by the police red squad on the Club at which valuable art objects were damaged or destroyed, was set forth in the testimony of Buchanan on record today in Judge J. A. Smith’s Court at the trial of a suit for $5,200 damages brought against the city as the result of the raid.”

However, it was the photograph that accompanied the story that really got my attention, it showed one of the artworks in question, before and after being damaged. Despite the fact that both the article and the photo’s caption failed to identify the subject matter of the artwork or the name of the artist who created it, there’s little doubt that it is the panel of the Scottsboro Boys described by Robert Storr in his biography on Philip Guston.

My educated guess is that the photo is of Guston’s very first public mural.

Further circumstantial evidence comes from comparing the newspaper photo of the damaged painting with photos of Guston’s renowned Mother and Child (1930), his first fully realized easel painting created when he was just 17.

Both compositionally and stylistically, they appear to be the work of the same artist, especially in the treatment of the faces. Remarkably, this early painting and the circumstances surrounding it have been written out of most of the accounts of Guston’s life and work, a situation that I hope will in part be remedied by the research I’ve presented here.