Siqueiros: Confronting Revolution & Censorship Defied

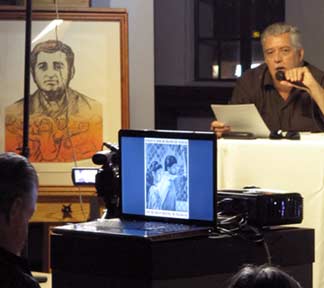

This article will address two recent events in Los Angeles having to do with the Mexican artist David Alfaro Siqueiros, the September 18, 2010 panel discussion A Print Dialogue: Siqueiros & The Graphic Arts, that took place at the Center For The Arts in Eagle Rock, California, and the recently opened Siqueiros in Los Angeles: Censorship Defied at the Autry National Center in Griffith Park. I was a participating panelist in A Print Dialogue, and I attended the Members Opening Reception for the Autry exhibit the day before the show opened to the public.

It was indeed an honor to have been a participant in the panel discussion A Print Dialogue: Siqueiros & The Graphic Arts, an event organized by the José Vera Gallery and sponsored by the Autry Museum.

The panel discussion was moderated by the Senior curator for the Museum of Latin American Art (MOLAA), Cynthia MacMullin.

Running through October 27, 2010, the José Vera Gallery is currently presenting Confronting Revolution: A Siqueiros Aesthetic, a stunning exhibition of prints by the revolutionary artist that set the context for the Print Dialogue panel discussion.

My fellow panelists and esteemed colleagues, muralist Wayne Alaniz Healy, independent curator Lynn La Bate, artist Luis Ituarte, and art historian Dr. Catha Paquette, helped to make the round-table discussion lively and informative. This post will include a rough transcript of my presentation at the round-table discussion, but first I would like to offer a brief review of the event.

Over 100 people filled the Center For The Arts, which is located in the beautiful Spanish Colonial Revival style structure that was first constructed in 1914 as the Carnegie Library Building; the classic mission architecture of the center provided the perfect venue for the evening’s dialogue. The proceedings were videotaped by filmmaker Jose Luis Sedano, who has been diligently filming events leading up to the unveiling of the Siqueiros América Tropical Mural And Interpretive Center now under construction.

There is much renewed interest in Siqueiros, no doubt because of the flurry of activity around his Olvera Street mural. Most people think of Siqueiros as a muralist, but he was also a master printmaker.

The panel discussion, and the exhibit at the José Vera Gallery, were designed to inform people of that fact. Art historian Dr. Catha Paquette and independent curator Lynn La Bate began the program with a scholarly look at the life and works of Siqueiros. Their separate presentations were thorough and exhaustive, covering many aspects of the artist’s philosophy, working methods, and place in art history. Still, I was amused by the wholly academic question broached by Paquette and La Bate, and taken up by members of the audience, as to whether the works of Siqueiros belonged to the Western “canon of art,” a matter the artist would no doubt have dismissed as bourgeois. The only “cannon” of interest to Siqueiros was the one pointed at the capitalist power structure. He said of his América Tropical mural;

“It is eloquent proof of how the intrinsic work of art respective to the current moment can be uniquely of revolutionary conviction. It is an eloquent display of the superiority of the collective work of democratic art in action over the wretchedly small efforts of the individual. It is the emergence of an expressive vehicle requiring monumental murals in the open air, facing the sun, facing the street – for the masses. It is a technical forecast of a near future’s art – the art of a new communist society.”

If Siqueiros has a place in the Western canon of art, it is in that long established branch were the “human condition” and the state of society have served as themes for artists. Dr. Paquette and La Bate (who by the way co-curated the Autry Siqueiros exhibit), used the term “social realist” to describe the art of Siqueiros, making the false assumption that the term would be readily understood by the audience.

As the term “social realism” had been bandied about, when my turn to lecture arrived I strayed from my prepared statement to give a brief history of the school, noting that; “in the 1930s there were three great schools of social realism, in America, in Germany before the rise of fascism, and in Mexico, each made enormous contributions to the history of art – but tonight I am called upon to talk about Siqueiros and the Mexican school.” I pointed out that social realism could be traced to “that first modern painter, Francisco Goya,” and it could later be found “in the works of Honoré Daumier,” but “the modern school of social realism as we know it today, began in New York in the year 1908.”

I then gave a brief but comprehensive description of the “Apostles of Ugliness,” those eight American painters who in 1908 defied the art world by painting the poor, immigrant, and working class populations living in New York slums. Social realism, I said, “is in fact a profoundly American school of art… and by ‘American’ I mean the land that extends from the tip of Argentina to the streets of L.A. and beyond.” I noted that social realism “is any art form that brings attention to the working masses and the poor, with the intention of provoking critical thought that leads to reformist or revolutionary action.”

The following commentary came from my prepared notes for the evening;

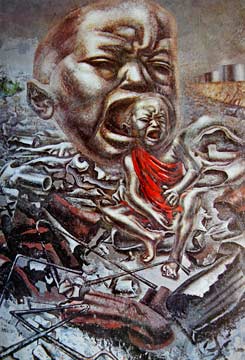

“I first stumbled upon the art of Siqueiros in the early 1960s when I was around 10-years-old. That initial encounter was with this nightmare of a painting, The Echo of a Scream. I had found a reproduction of the image and became transfixed by it. I struggled to comprehend its meaning, but the artwork only gave me the feeling that there was something truly menacing in our world that no one had bothered to tell me about.

Later on as teenager, when I began to study the works of Siqueiros in earnest, I discovered that he had been moved to paint this work in 1937 when the Japanese Imperial army bombed Shanghai, China. Siqueiros had loosely based his painting upon a news photograph of the carnage.

Much has been made of Siqueiros being opposed to easel painting, and his eschewing it in favor of the more democratic public art form of muralism. I believe this to be a misconstruing of the facts, exacerbated by the artist’s own lofty proclamations. In 1923, a number of left-wing artists formed the Union of Technical Workers, Painters, and Sculptors, or El Sindicato (the union) as it was commonly referred to, and Siqueiros would write their first manifesto in December of that same year. It was co-signed by Diego Rivera, José Clemente Orozco, and a number of others. I am going to read an excerpt from the manifesto, since it exemplifies the ideals of the Mexican school that Siqueiros held fast to his entire life;

‘To the indigenous races humiliated through the centuries; to the soldiers converted into hangmen by their chiefs; to the workers and peasants who are oppressed by the rich; and to the intellectuals who are not servile to the bourgeoisie:

We are with those who seek the overthrow of an old and inhuman system within which you, worker of the soil, produce riches for the overseer and politician, while you starve. Within which you, worker in the city, move the wheels of industries, weave the cloth, and create with your hands the modern comforts enjoyed by the parasites and prostitutes, while your own body is numb and cold. Within which you, Indian soldier, heroically abandon your land and give your life in the eternal hope of liberating your race from the degradations and misery of centuries.

Not only the noble labor but even the smallest manifestations of the material and spiritual vitality of our race spring from our native midst. Its admirable, exceptional, and peculiar ability to create beauty – the art of the Mexican people – is the highest and greatest spiritual expression of the world-tradition which constitutes our most valued heritage. It is great because it surges from the people; it is collective, and our own aesthetic aim is to socialize artistic expression, to destroy bourgeois individualism.

We repudiate the so-called easel art and all such art which springs from ultra-intellectual circles, for it is essentially aristocratic. We hail the monumental expression of art because such art is public property.

We proclaim that this being the moment of social transformation from a decrepit to a new order, the makers of beauty must invest their greatest efforts in the aim of materializing an art valuable to the people, and our supreme objective in art, which is today an expression for individual pleasure – is to create beauty for all, beauty that enlightens and stirs to struggle.’

El Sindicato’s manifesto was widely distributed, and had considerable effect. Clearly, as Echo of a Scream amply proved, Siqueiros was able to create an easel painting imbued with radical populist ideals, so easel painting in and of itself was not the problem; the trouble was in the private ownership and commodification of art, a question that remains unresolved. In his pursuit of a democratic art form, Siqueiros turned to the world of print making.

I am going to talk about a specific print that Siqueiros published in 1970, but first, it is necessary to examine one of his previous artworks, a mural that has a direct link to the print in question.

In 1944 Siqueiros painted this monumental allegorical mural depicting a female figure representing New Democracy (the name of the painting), bursting out of the earth’s crust. The work portrayed the impending victory of allied forces over the fascist armies of the Axis powers, but it also implied more. New Democracy carries the torch of liberty in one hand, and a flower of peace in the other.

The political and artistic impetus behind this mural was one and the same, the New Democracy painting was the product of what Siqueiros called the New Realism in aesthetics, a didactic art that would in the artist’s words “aim to become a fighting educative art for all.” In New Democracy Siqueiros painted a faceless Nazi soldier in death, his lifeless hands covered in blood; side panels (not shown) portrayed the victims of fascist brutality. But while victory over fascism is more than suggested in the mural, the artist described it as an incomplete triumph. New Democracy is still shackled by the heavy chains dangling from her wrists, and she struggles tremendously to wrest herself free from the living rock that imprisons her.

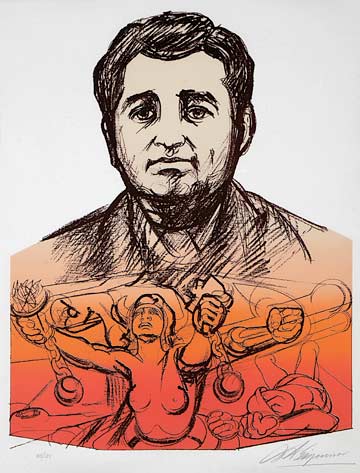

Now we leap from the New Democracy mural of 1944, to the lithograph Siqueiros created in 1970. As many in the audience are aware, forty years ago up to 30,000 Mexican Americans in East Los Angeles marched against the Vietnam war in what was called the Chicano Moratorium—it was a massive protest that demanded an end to the war, but the community also had other grievances; putting an end to poverty, racism, and police brutality being high priorities. The huge march ended with a peaceful rally in Laguna Park.

The Los Angeles Police Department and the Los Angeles County Sheriffs responded to this unprecedented protest with extreme violence.

Officers attacked the crowded park using clubs and tear gas, protesters fought with their bare hands to defend the park, and the violence spiraled out of control. As the riot spread into the community, the police began using live ammunition against the protestors; they would kill four people that day… Angel Diaz, Lyn Ward, Gustav Montag, and Ruben Salazar.

Ruben Salazar was an award-winning columnist for the Los Angeles Times, and also the news director for the Spanish language KMEX television station. As such, he openly criticized the police for racist conduct in his columns, which did not endear him to the authorities.

On August 29, 1970, Salazar was covering the Chicano Moratorium for KMEX when the violent clashes broke out. He took refuge in the Silver Dollar Cafe on Whittier Boulevard. The L.A. County Sheriffs descended upon the cafe, and a deputy fired a 10-inch long metal tear gas projectile into the premises, it hit Salazar in the head and killed him. Forty years later, the police have still not released the files they possess on the subject of Salazar’s death. The Sheriff’s Dept. maintains that the killing was a “tragic accident,” but many in the community feel it was a “targeted assassination.”

Siqueiros responded to the state suppression of the Chicano Moratorium and the killing of Salazar with this lithograph print, which he titled; Heroic Voice (though its also known as “Por la Raza” – For the Race). It is not simply a portrait honoring the slain newsman, but a political statement with broad implications. In viewing this print, it should become obvious as to why I brought your attention to the New Democracy mural; Siqueiros merged the two images in his lithograph. Beneath the beaming face of the assassinated Salazar, New Democracy still struggles to free herself from bondage, her shackles still in place. The message of the print is unmistakable, the struggle against fascism continues.

I attended the 40th anniversary march and rally to commemorate the original Chicano Moratorium. On August 28, 2010, up to 3,000 people marched to what is now called Ruben Salazar park, only this time the protest was against the wars in Afghanistan and Iraq. I took this photograph in front of where the Silver Dollar Cafe used to stand. As the multitudes passed this spot, which bears no memorial plaque to Salazar… mounds of flowers were tossed upon the sidewalk to honor the slain journalist.”

My talk then concluded with the following:

“Simón Bolívar led the Independence movement that crushed Spanish colonialism in South America. Envisioning a hemispheric confederation of the newly liberated countries, he said; ‘the name of our country is América.’ That vision in part guided the hand of Siqueiros, but he held a much larger conception of the world that rejected the divisions of class, nationality and ethnicity.

It has been said in some quarters, that history is written by the victorious. If that is so then the official histories of our continent have been penned by colonizers, imperialists, and oligarchs. However, history is also a people’s memory, and Siqueiros gave us the visual representations of that memory. He painted the other America, the one seen through the eyes of the indigenous, the downtrodden, the compesino, and the exploited urban workers.

Siqueiros and his associates in the Mexican School of social realism, confronted the world crisis of their day through their art. Contemporary artists face a social crisis of unparalleled dimension. We were given a preview of the ecological collapse that awaits us with the recent BP oil disaster in the Gulf of Mexico. The U.S. is currently fighting wars overseas as millions of Americans loose their jobs and homes. The border of Mexico is being militarized, and nearly 30,000 Mexicans have been killed in the so-called ‘war on drugs.’ Postmodern art now dominates the international art scene with its detached, cynical, apolitical stance. Its casual indifference to the plight of humanity makes postmodernism a totally inappropriate art for today; it is time for a new social engagement on the part of artists.

I believe artists should embrace, study, and analyze the works of Siqueiros and the Mexican School, not for nostalgic reasons, or misled notions that the past can be superimposed on the present. We need to comprehend the motivations, triumphs, and errors of the Mexican School. With such an understanding, we will be that much closer to bringing about a new social realism for the 21st century.”

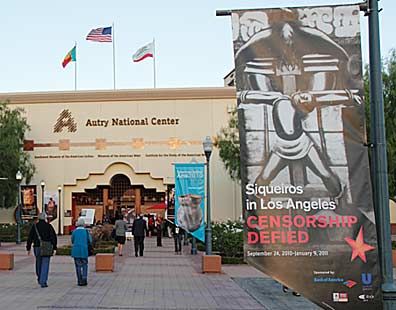

Siqueiros in Los Angeles: Censorship Defied

“Censorship Defied” at the Autry National Center is a must see, groundbreaking exhibition. I commend the Autry for mounting the show, and applaud curators Luis C. Garza and Lynn La Bate for their hard work and dedication in pulling off such a grand exhibit.

The show offers a multitude of interactive and informative digital displays, historic photographs and documents, ephemera such as old postcards, books, and flyers, and some stunning works created by American social realist artists from 1930’s Los Angeles, such as Edward Biberman and Millard Sheets – which provide much needed context for the story of Siqueiros in L.A.

The show also contains artworks by a number of Mexican social realists who worked with Siqueiros; José Clemente Orozco, Diego Rivera, and Luis Arenal. Of course the crowning works in Censorship Defied are by Siqueiros, and his print works are displayed along with a handful of his original paintings.

The opening portion of the exhibit is extremely powerful, with the initial artworks encountered a dizzying array of majestic prints by Siqueiros, Orozco, Rivera, Leopoldo Méndez, and Luis Arenal. One hardly knows where to look first.

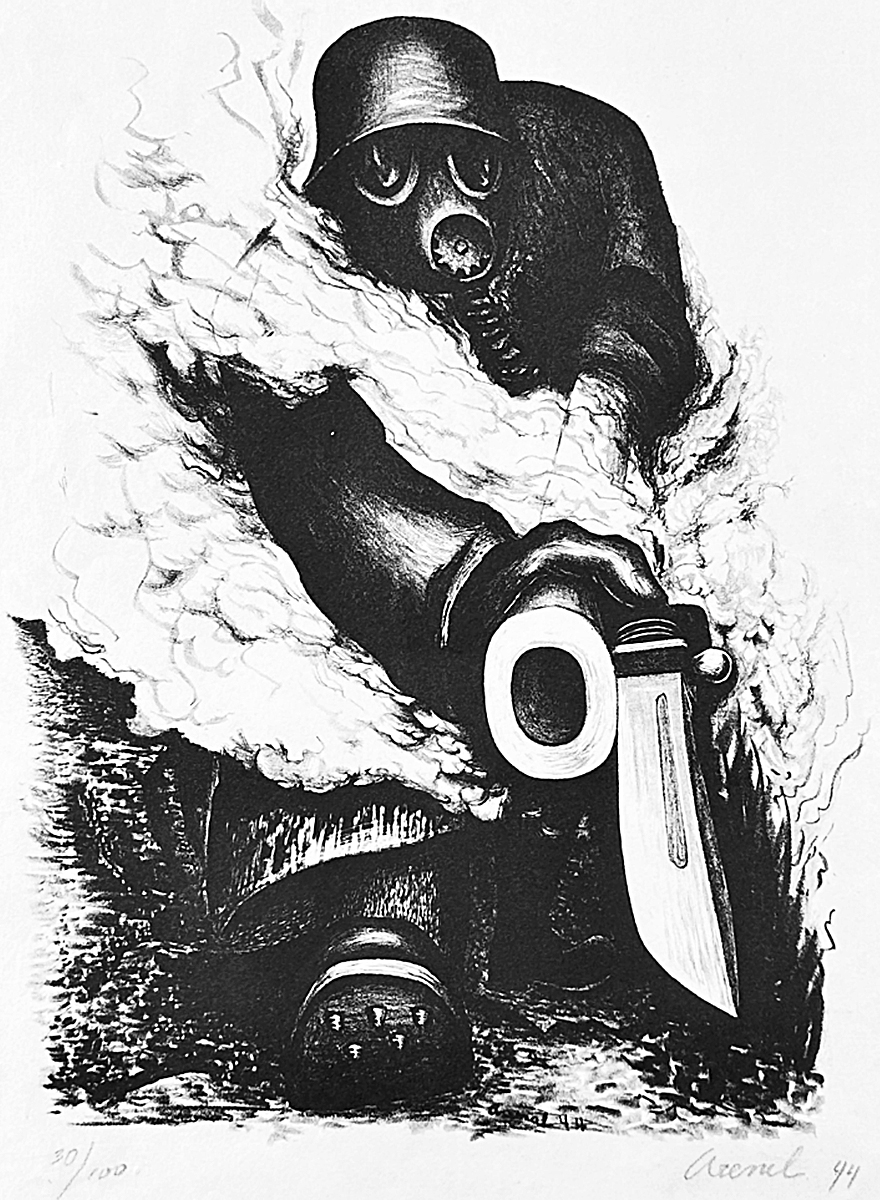

Particularly riveting was the black and white lithograph by Luis Arenal depicting a gas-mask wearing soldier marching towards the viewer from out a cloud of poison gas. The artist created his print as WWII was raging. The faceless combatant thrusting his bayoneted rifle forward makes for a chilling image that could have been printed today.

There is much to be scrutinized in the first part of this show, so much so that a second trip to the exhibit is required to absorb it all. There is the 1930 print suite, Siqueiros: 13 Grabados, the small primitive woodcuts the artist made in a cell at the notorious Lecumberri prison after being given a six month sentence for participating in a May Day march, and there is a small but exquisite painting Siqueiros created in pyroxylin (which is essentially car lacquer). Titled Marcha Revolucionaria (Revolutionary March), the little painting packs all the power of one of the artist’s monumental works. It explodes with energy, and unusual for the artist, the work was painted on a sheet of copper as was the practice before the advent of stretched canvas.

While I have been aware of the paintings of Martin Charlot for a while, I had the pleasure of meeting him in person for the first time when giving my talk at the Center For The Arts in Eagle Rock. Martin is the son of Jean Charlot, who was a major figure in the Mexican muralist movement.

Jean Charlot’s 1933 color lithograph, Woman Standing with Child on Back, is included in the Autry exhibit. Diego Rivera credited Jean Charlot for having revived the art of frescoe mural painting, in fact it was Charlot who painted the very first frescoe mural in Mexico with socio/political content, his Massacre in the Great Temple, a 1923 wall painting in the Escuela Preparatoria of Mexico City depicting the crushing of the Aztec empire by invading Spanish Conquistadors.

Martin Charlot is a soft-spoken, unassuming fellow, and quite a remarkable painter, so it was a pleasure to walk through the Autry exhibit with him, stopping before some our favorite works to exchange comments. He brought my attention to Angels Flight, a familiar oil on canvas by Millard Sheets, telling me that it was his “favorite” work by the artist (Sheets was one of the assistants who helped Siqueiros paint the Worker’s Meeting mural at Chouinard Art School). Martin and I also stopped before a lithograph by Luis Arenal, Mujer de Tasco (Woman of Tasco), a beautifully drawn representation of an indigenous woman’s head. We were both struck by how Arenal’s lithograph resembled the work of the famed German artist, Käthe Kollwitz.

Another transcendent highlight for me that evening was meeting Eric Garcia and his family. Eric is the son of the celebrated social art historian and scholar, Shifra Goldman. In 1968 Ms. Goldman was responsible for initiating the campaign to preserve the Siqueiros mural, América Tropical. She was also instrumental in restoring and moving his last mural, Portrait of Mexico Today, 1932, to the Santa Barbara Museum of Art in California, where it now resides. To say that the presence of Goldman looms large in the circles that appreciate Siqueiros is an understatement. Tragically, Ms. Goldman has slipped into advanced Alzheimer’s and is no longer cognizant. Her once towering intellect has been wiped away, and we are the poorer for it.

I first met Ms. Goldman in 1984, and over the decades we continued to cross paths, never failing to have interesting conversations regarding the political dimensions of art. She believed, as I do, that art and politics are inseparable. She once told me that she would “never” lecture about Frida Kahlo, unless she could use such an occasion to inform her audience about Aurora Reyes Flores (Mexico’s first female muralist), and the “dozens of other women artists” who contributed so much to the greatness of Mexican art. Goldman could be irascible and confrontational, but rarely was she far from the truth.

When I asked Eric how he thought his mother would react to the Autry Siqueiros exhibit, he chuckled that “She would probably find something to loudly complain about.” Eric’s remark had a ring of truth about it – and not just because it was an accurate description of Shifra’s disposition. I have much more to say about the Autry’s Censorship Defied exhibition – including some criticisms – but for now I shall refrain from further comment and simply urge the reader to attend this most remarkable and historic exhibit. In the weeks to come this web log will be updated with further examinations of the show.

Updates:

¡Shifra Goldman – Presente! Art historian Dr. Shifra M. Goldman died in Los Angeles on the afternoon of Sept. 11, 2011, from Alzheimer’s dementia.

Siqueiros Paisajista/ Siqueiros: Landscape Painter, was a blockbuster exhibition at the Museum of Latin American Art (MOLAA) in Long Beach, California. It was the first exhibit to present the fiery and volatile landscape paintings created by the Mexican muralist. The show was organized by the Museo de Arte Carrillo Gil of Mexico City, which holds the largest collection of easel paintings by Siqueiros. The show ran until January 30, 2011.

Siqueiros & the Mexican School of Social Realism. October 23, 2010. 6:30 p.m.

José Vera Gallery, Eagle Rock. As part of the cultural programming surrounding their Siqueiros print exhibit, Confronting Revolution: A Siqueiros Aesthetic, Mark Vallen presented a multi-media lecture on the Mexican school of social realism and how it continues to be relevant in the 21st century.

David Alfaro Siqueiros & the “Bloc of Painters.” American Social Realism in the 1930s

Nov. 6, 2010. 6:30 p.m. at the Mexican Cultural Institute, Olvera Street. When Siqueiros arrived in Los Angeles in 1932 he assembled what he called the “Bloc of Painters,” a group of American artists whose members assisted the Mexican muralist in painting three monumental wall paintings in LA. Bloc members included Rubin Kadish, Harold Lehman, Fletcher Martin, Phil Paradise, Murray Hantman, Barse Miller, Paul Sample, Philip Guston, Millard Sheets, and many others. Who were the Bloc Painters and what contributions did they make to art and culture in the United States? By combining projected images with his lecture, Los Angeles artist Mark Vallen brought to light that buried history. Sponsored by the Amigos de Siqueiros.