Alfredo Ramos Martínez: Picturing Mexico

I have long admired the works of the Mexican artist Alfredo Ramos Martínez (1871-1946), and over the decades I was fortunate to see a handful of original works by him. I was always puzzled that so few in the U.S. remembered him, especially those of us living in Southern California where Martínez came to live and exercise considerable influence. Once a renowned and much sought after artist, the sands of time have buried Martínez, but an amazing exhibit of his works at the Pasadena Museum of California Art, Picturing Mexico: Alfredo Ramos Martínez in California, should stimulate a new appreciation for his art. Sadly the PMCA closed permanently in October 2018.

Historians and artists alike have often referred to Diego Rivera, David Alfaro Siqueiros, and José Clemente Orozco, three eminent 20th century artists of Mexico, as Los Tres Grandes (the big three). It is of course a reductionist view of history, as there were many great Mexican artists from the period, and Alfredo Ramos Martínez was certainly one of them. Those familiar with his life and works have variously described him as the “Father of Modern Mexican Art,” or the “Father of Mexican Modernism,” titles that are not exaggerations.

Some have said the paintings of Martínez “do not sustain the interpretation” of his being a revolutionary artist, an opinion that ignores the historic role Martínez played in transforming Mexican art and literally founding a national aesthetic for his country. He was not a rabble-rousing communist like his contemporaries Rivera and Siqueiros, they placed their art at the service of revolution, but the oeuvre of Martínez plainly shows that he painted the indigenous poor and common people of his native land. From our perspective that may not seem like much, but one must consider Mexico as it was in the early 20th century; an underdeveloped and impoverished country where the dark-skinned majority was ruled over by a light-skinned minority of corrupt oligarchs – and that ruling class preferred classical European art to anything produced in Mexico.

It is a mistake to say the art of Martínez was not political in nature; his paintings were generally not militant or confrontational like those of his colleagues, as if only paintings and prints of insurrectionary Mexican peasants armed with rifles and machetes constitutes “political art.”

The 57-year old Martínez left Mexico in October 1929 to settle in Los Angeles, a city tottering on the brink of the Great Depression. He was embraced by those captivated with Mexican aesthetics, and quickly gained a following. In 1930 José Clemente Orozco painted the very first modern fresco in the U.S., his Prometheus mural at Pomona College. In 1931 Diego Rivera painted four murals in the San Francisco Bay Area, and during his 1932 political exile in Los Angeles, Siqueiros painted three murals, the best known being his América Tropical mural on Olvera Street. In 1934 Martínez painted murals for the chapel of the Santa Barbara Cemetery in Santa Barbara, California. My photographs presenting details of Martínez’ mural illustrate this article.

The chapel of the Santa Barbara Cemetery was designed by the American architect and painter, George Washington Smith, who led the Spanish Colonial Revival style of architecture in the U.S. during the early 20th century.

The chapel was completed and dedicated in 1926, and Martínez received a commission to paint the murals in 1934; his murals were controversial for not including the traditional religious iconography that was popular at the time.

In his history of the Santa Barbara Cemetery, The Best Last Place, author David Petry wrote that the cemetery’s manager and board member, William Bryant Jr., complained that the murals “impaired his ability to sell niches in the chapel, or to sell the use of the chapel for services.”

Over the portico of the chapel Martínez painted the resurrected Christ surrounded by angels bearing lilies, the Christian symbol of purity. The walls above the aisles were painted with scenes of the clergy, laity, and angels in a devout procession towards the Messiah.

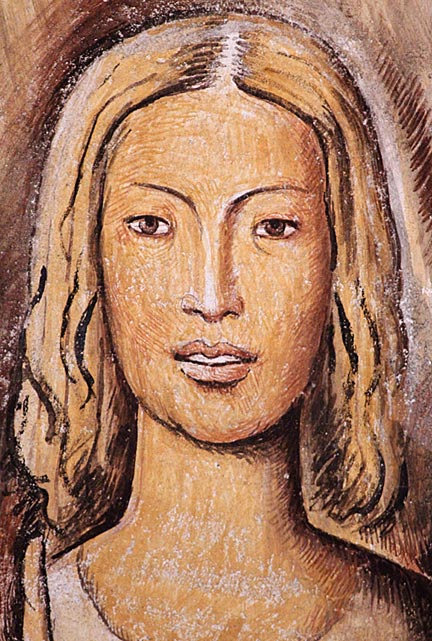

Head of a Nun, the tempera on newsprint drawing by Martínez exhibited by the PMCA in Picturing Mexico, is a study for one of the figures in this section of the chapel mural.

The mural’s aesthetics are informed by an austere and rough modernism, the composition dictated by the artist’s attention to architectural details, and the figures having an almost geometric quality to them.

With the exception of a group of Mexican Indian women penitents, all of the figures in this portion of the painting are blonde Caucasians.

However, Martínez painted an extraordinary scene in the dome above the chapel’s Altar. From the Nave of the chapel one can see the monumental representation of the Lord God, his hands raised to bless humanity.

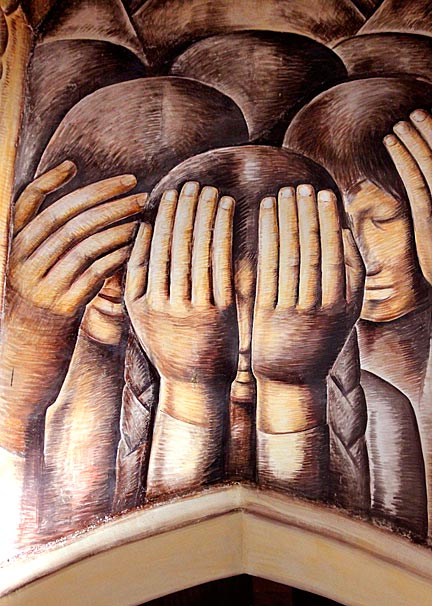

Again, the figure is painted in severe Modernist style, but it is the Mexican Modernism that found inspiration in the “primitive” style of the ancient Maya and Aztecs. Painted on the dome directly across the representation of God, but hidden from view from those in the chapel Nave, is a group portrait of Mexican Indian mourners.

They are the dark-skinned wretched of the earth, the invisible ones that silently suffer the indignities heaped upon them by a cruel and indifferent world. They cover their eyes with trembling hands, and huddle together in their misery.

But by placing them opposite his portrait of the Lord, Martínez was saying that it is the poor and vulnerable who are closest to God.

Religious themes were always a current in the works of the artist, who was obviously a pious man.

Millard Sheets, a leading member of the Southern California arts community, befriended Martínez and promoted his works.

As the chair of the new art department at Scripps College in Claremont, California, Sheets organized a 1937 on-campus exhibit of Martínez’ art, and in 1945, under the sponsorship of Sheets, Scripps commissioned Martínez to create a 100-foot long mural for its Margaret Fowler Memorial Garden. It was to be his last work. The artist began the mural but did not complete it due to his death in 1946 at the age of 73. Today the unfinished mural titled The Flower Vendors remains a popular destination on the Scripps campus.

Here it is necessary to examine the role Martínez played in Mexican society prior to coming to the United States. After the Mexican Revolution began in 1910, art students at the San Carlos School of the National Academy of Fine Arts called for a strike against the conservative institution.

The strike began in 1911, and took aim at the school’s academic training methods, which disallowed students to draw from live models.

The outlook of the students was shaped by the country’s ongoing revolution, and they expanded their demands to include, not just an end to the hegemony of Academic art, but the establishment of a Free Academy where meals, rooms, and art supplies would be free.

Concurrently, the radical democrat Francisco Madero and the peasant armies of fellow revolutionaries like Emiliano Zapata and Pancho Villa successfully drove the longtime dictator Porfirio Díaz from power, and Madero became president in 1911.

In the continuing strike art students demanded the nationalization of the country’s railroads in solidarity with the revolution. José Clemente Orozco was a leader of the Student Strike Committee, and Siqueiros participated in the strike as a young student. Eventually the strike was won, the academic art curriculum was dropped, students were allowed live models, and by 1913 Alfredo Ramos Martínez became the Director of the National Academy. Martínez broke from the Greco-Roman traditions of European academic art, instead insisting that Mexico’s land, history, and indigenous people were the only subject matter needed for the creation of great art. He opened the first Open Air School of painting in Mexico, which emphasized direct observation in the creation of landscapes and depictions of peasant life; Siqueiros was one of his students. Martínez not only revolutionized the Academy, he helped to change the face of Mexican art.

But in 1913 Mexico, more than just the directorship of the Academy would change hands. The revolution was betrayed when General Victoriano Huerta entered into a conspiracy with the U.S. Ambassador to Mexico, Henry Lane Wilson. The two plotted to carry out a coup d’etat against the reformist Madero, and on Feb. 18, 1913, Huerta seized power militarily and arrested Madero. Days later Huerta had President Madero and Vice-President José María Pino Suárez assassinated by a military firing squad. One could say that after the treacherous murder of the popular Madero by right-wing forces, the Mexican revolution intensified and deepened – but that is another story.

Walking through the Martínez exhibit at the Pasadena Museum of California Art is akin to walking through the pages of a gorgeously illustrated history book that tells the intertwined tales of Mexico and the United States. Few artists have made that tangled relationship as clear as Alfredo Ramos Martínez. The works on exhibit were all created during the artist’s stay in the U.S., and include landscapes and portraits, as well as political and religious statements. The overwhelming number of works in the show express the artist’s love of Mexico and its people, and he no doubt appreciated their many historic links to California and its population.

Some of the most startling pieces in the exhibition are the graphic works Martínez created on printed newspaper pages. He drew and painted directly on actual U.S. newspaper pages he mounted on canvas or board; the artworks are intensely political if only for their extreme juxtaposition of cultures. One such work is El Defensor (The Protector), a drawing in tempera and conte-crayon drawn on a June 5, 1932 edition of the Los Angeles Times. The drawing is a portrait of a furious young compesino, his hand clenched into a fist as if ready to deliver a blow. Text from the paper’s mundane classified ads bleed through the drawing. El Defensor is one of the strongest artistic statements Martínez made in California during that period.

The irony Martínez presented to us in El Defensor reaches across time, as he knew it would. When he made the drawing the U.S. government was involved in a massive forced repatriation campaign of Mexicans in the U.S., up to two million were apprehended, placed on trains, and deported. The City of Los Angeles was also involved in deporting tens of thousands, and at the time, the policy of deporting Mexicans was approved of by the Los Angeles Times.

— // —

Sadly the Pasadena Museum of California Art (PMCA) permanently closed in October 2018.

Read more about the artist at, Ramos Martínez & The Flower Vendors.

Addendum:

On Sunday March 23, 2014, Scripps College will hold a symposium titled, Picturing Mexico: Alfredo Ramos Martínez. A number of interesting panel discussions are scheduled, culminating in the viewing of the artist’s celebrated fresco mural, The Flower Vendors.

The PMCA is also presenting Serigrafía, an exhibit of thirty silkscreen prints created by Chicano/Latino artists from the 1970s to the present; I am pleased to have one of my prints in the exhibit. A correlation between the prints and the works by Martínez can be seen, especially by those who are aware of the march of history.

Picturing Mexico: Alfredo Ramos Martínez in California will travel to the Nevada Museum of Art in Reno, Nevada, where it will run from May 10, 2014 to Aug. 17, 2014.