Roger Scruton at TRAC 2014

When hundreds of arts professionals from all over the country, indeed from all across the globe, come together at a four day symposium to enthusiastically discuss the future of realism in painting… it could be said that something might be afoot in the art world. TRAC 2014, or The Representational Art Conference, took place from March 2 through March 5, 2014 at the beachfront Crowne Plaza hotel in sunny Ventura, California. I attended a few of the programs offered on Monday, March 3rd, and offer my observations of the conference with this article. I do so as a figurative realist artist, and a proponent of social realism.

On the day I was present there were around 500 or so artists, academics, curators, critics, and students gathered for the event. I am certain that overall attendance for the entire conference was much higher. TRAC 2014 was the second international conference on representational art to be presented by the California Lutheran University (CLU) of Thousand Oaks, California, the first having been held in 2012. TRAC was organized by Michael Pearce, associate professor of Art and curator of The Kwan Fong Gallery at California Lutheran University, where he also teaches figurative painting. Co-founder Michael Lynn Adams is also a realist painter and a visiting lecturer of drawing and painting in the CLU art department.

The official catalog of TRAC 2014 affirmed that the event’s organizers “believe that there has been a neglect of critical appreciation of representational art well out of proportion to its quality and significance; it is that neglect that The Representational Art Conferences seek to address.” It was further stated that the purpose of the event was “not to establish a single monolithic aesthetic for representational art, but to identify commonalities, understand the unique possibilities of representational art, and perhaps provide some illumination about future directions.” Lofty and praiseworthy ideals. I certainly concur that representational art has been overlooked if not ignored… but did TRAC 2014 deliver on its mission?

My day at TRAC 2014 began with the keynote address delivered by British conservative philosopher, activist, and author Roger Scruton. Well-known in Britain, Scruton remains an obscure figure for most Americans, apart from those conservatives that take pleasure in reading weighty cultural/political criticism.

He is perhaps best known, at least in artistic circles, for his 2009 BBC documentary, Why Beauty Matters, which hauled postmodern art over the coals while praising the virtues of traditional representational art.

His documentary certainly won Scruton the admiration of embattled traditionalists in the arts, and his condemnation of postmodernism undoubtedly led the organizers of TRAC 2014 to request that he appear as keynote speaker. But Scruton’s view of the arts has its detractors. Four years ago I wrote about Scruton on this very web log, reviewing his BBC documentary in an article also titled Why Beauty Matters, so I was interested in hearing his public address.

Hundreds packed the “Top of the Harbor” Ballroom at the Crowne Plaza to hear Scruton deliver a stimulating address, and they were not disappointed. With dry wit and calm demeanor, the soft-spoken thinker disassembled postmodern art and philosophy, bedazzling his audience for nearly an hour. In describing the impact of postmodernism on the arts, he paused occasionally to verbally flay this or that celebrity art star.

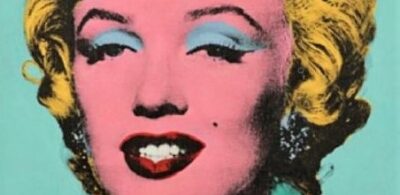

Starting with the progenitor of conceptual art, Marcel Duchamp, Scruton called that artist’s 1917 porcelain urinal: “a joke against art that has been elevated to art.” Moving on to the 1960s when postmodernism began its ascendancy, Scruton said: “I know it is heresy to say so, but Warhol’s Brillo boxes are not original, nor are they works of art.” Then Scruton arrived at the present, where his flaming arrows met multiple targets.

He ridiculed the bisected animals displayed in tanks of formaldehyde by Damien Hirst, declaring that Hirst was abetted by sycophants and his success was due only to “a ballet of complicit deception.” The unmade bed and personal detritus of Tracey Emin was assessed as so much rubbish by the sharply critical philosopher, who then disparaged the “particularly loathsome Chapman Brothers” for producing art that “is not new but simply transgressive.”

As for Jeff Koons and his insufferable Balloon Dog sculptures, Scruton said… “they deserve only to be punctured.”

All of the above was music to the ears of those gathered. Scruton could hardly have found a more receptive and appreciative audience. I admit chuckling to his jibes made at the expense of today’s postmodern art stars, and it was definitely refreshing to hear someone rhetorically stick a knife into the elite art world. Scruton passed judgment on postmodernism as a fierce critic of an art world obsessed with celebrity and very expensive though meaningless bobbles.

Scruton straightforwardly blames liberalism and socialism for the ongoing fall of Western civilization. In his address he said that “if you make the mistake of going to a university to study philosophy,” you will be indoctrinated with the ideas of Jacques Lacan, Jacques Derrida, and Michel Foucault – postmodern theorists admired by the left. That notwithstanding, the creaky left-wing Noam Chomsky, Professor Emeritus at Massachusetts Institute of Technology, believed Lacan was an “amusing and perfectly self-conscious charlatan,” that Derrida’s scholarship was “appalling” and “failed to come close to the kinds of standards I’ve been familiar with since virtually childhood,” or that he said of Foucault: “I’d never met anyone who was so totally amoral.” This is not to say I place any credence in Chomsky’s moth-eaten leftism.

Scruton recommended that in order to fully understand the intellectual bankruptcy of postmodernism, the audience should read the book, Fashionable Nonsense (published in the U.K. as Intellectual Impostures). I also suggest reading the book for its take down of postmodern theory. But does Scruton know that there are socialists who also highly recommended the book? Or that it was written by Alan Sokal, who once said: “I confess that I’m an unabashed Old Leftist who never quite understood how deconstruction was supposed to help the working class. And I’m a stodgy old scientist who believes, naively, that there exists an external world, that there exist objective truths about that world, and that my job is to discover some of them.”

Believing that postmodernism is the result of Marxist philosophy, Scruton upbraided postmoderns Damien Hirst and Tracey Emin. But Hirst is the darling of capitalist collectors and through their largess has become the richest artist in the world, now worth $1 billion. Emin voted Tory, admires the conservative Prime Minister David Cameron, and created an original work of art for him that hangs at 10 Downing Street. The ridiculous Gilbert and George conceptual art team also votes Tory, and once said, “We admire Margaret Thatcher greatly. She did a lot for art. Socialism wants everyone to be equal. We want to be different.” To be fair, Scruton was critical of Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher, and he extolled traditional conservatism over Thatcherism. That notwithstanding, it does seem to me that some conservatives have inexplicably embraced postmodern art.

Scruton’s defense of traditional art is part and parcel of his overall campaign against liberalism. In 1982 he became the chief editor of The Salisbury Review, a position he held until the year 2000; he continues today as a consulting editor for the publication. During Scruton’s tenure as chief editor, the Salisbury Review poured scorn upon the peace movement, unions, multiculturalism, immigrants, feminism, and yes, non-traditional art. The Review’s editorial policy remains the same today.

If you read The Meaning of Margaret Thatcher, Scruton’s obituary for the divisive Iron Lady published by The Times of London, you will have a better understanding of the man’s politics. He said that Thatcher appeared on the U.K. political scene “as though by a miracle,” implying that she was a “savior” who broke “the power of the unions,” fought the “socialist apparatchiks” of the country’s educational system, and restored national pride with “the Falklands war.” He could have mentioned that Thatcher instituted huge budget cuts to government arts funding, but he choose to overlook that particular miracle.

Throughout the TRAC address, Scruton peppered the talk with selected projected images or text. When he stated that “the disease of Kitsch effects more than art,” he brought up a photo of commercially available, mass produced gaudy statuettes of the baby Jesus and Mother Mary, all wrapped in cellophane and bedecked with price stickers. Here he spoke of postmodernism having stripped the sacred from our lives with its moral relativism, loss of belief, and repudiation of truth and beauty; and though people still have an intrinsic sense of the sacred – love of family, nature’s beauty, our feelings regarding birth and death – we are still swept along by the daily sacrileges of the postmodern spectacle. With some resignation Scruton remarked: “Maybe we are asking too much of people” when trusting they will abandon kitsch. The inherent contradiction is that the cellophane swathed baby Jesus was not just maliciously created by godless commies, it was produced and marketed by capitalists intent on making gobs of money.

At the beginning of his talk Scruton said that “we think reality can be captured in better terms,” than has so far been offered by the postmodern school. After sketching the outlines of art’s current predicament, he averred, “Don’t we have anything to contrast with this? That is what all of you people in this room are doing.”

At the end of his address, for which he received a standing ovation, there was a vibrant question and answer session.

A young man asked a simple and naive question, “How do we change this situation?” To which Scruton responded with the unflappably British, “Right.” He elaborated that “it’s very hard to change a whole culture… all one can do is start something and see what happens.” But he hedged his bets by quoting from the 1845 Theses on Feuerbach by Karl Marx, “The philosophers have only interpreted the world, in various ways: the point, however, is to change it,” to which Scruton added… “and look at how that turned out.”

One last question was put to Scruton from the audience concerning the role of money in the art world. The new reality of the price tag being more important than the art is somewhat difficult to overlook these days, with multi-billionaire oligarchs shaping the art world through their relentless acquisitions. Scruton is correct in saying the sacredness of art is being violated by this economic relationship. He acknowledged that money has been a corrosive force in art, but seemed at a loss to say anything else. I would have liked to hear more.

For instance, what would Scruton say about Charles Saatchi, the King Maker of the postmodern art scene in the UK? In the 1970s Charles and his brother Maurice started the advertising agency, Saatchi & Saatchi. In 1979 Margaret Thatcher hired the ad agency to create an advertising campaign for the Conservative Party’s 1979 election effort against the left-wing Labour Party. The agency’s Labour Isn’t Working series of posters, flyers, and billboards are credited with helping to sweep Thatcher into power. In 1985 Saatchi founded London’s Saatchi Gallery, launching the career of many a postmodern artist, and changing the face of British art.

In September 2012, the British debate forum Intelligence Squared, hosted an amazing discussion between Roger Scruton and Terry Eagleton titled The Culture Wars (watch the video of the encounter here). A Professor of Cultural Theory at the National University of Ireland, the author of some forty books, and a left-wing socialist, Eagleton debated Scruton on the subject of art and culture; What is it and why is it important? How does it impact us? What role does tradition play in art? What is the future of art in a globalized world? At one point in the debate Eagleton said to Scruton, “We’re in danger of agreeing too much.”

Those who could not attend TRAC 2014 will want to watch the The Culture Wars video, not just to see Mr. Scruton engaged in a “smack down” with an intellectual adversary from the left, but to also get a glimpse of how to broaden our understanding of art and the crisis it faces.

— // —

Sir Roger Scruton died on January 12, 2020 at the age of 75.

For more on Scruton read my essay Why Beauty Matters, and the second part of my review of The Representational Art Conference, TRAC 2014: Part II.