Ramos Martínez & The Flower Vendors

On March 23, 2014, I attended the symposium at Scripps College in Claremont, California titled Picturing Mexico: Alfredo Ramos Martínez.

Held to deepen public knowledge about the Mexican artist, the event was held in conjunction with the not to be missed exhibit at the Pasadena Museum of California Art, Picturing Mexico: Alfredo Ramos Martínez in California.

The symposium offered three separate talks by experts in their fields, all pertaining to the art of Martínez. After their presentations the three lecturers reconvened as panelists for an informative panel discussion moderated by arts writer, Suzanne Muchnic. A lively question and answer period followed, after which the symposium concluded and attendees walked a short distance to view The Flower Vendors, the fresco murals Martínez painted in the college’s Margaret Fowler Garden.

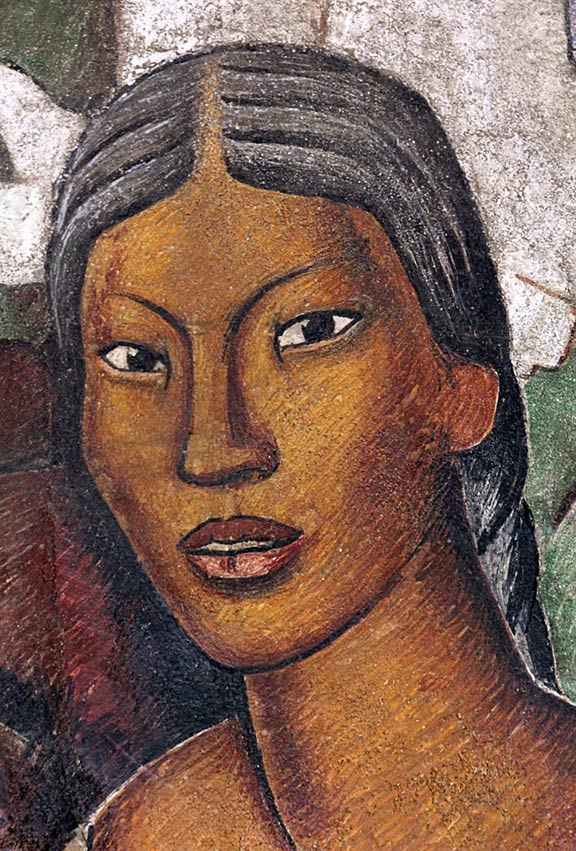

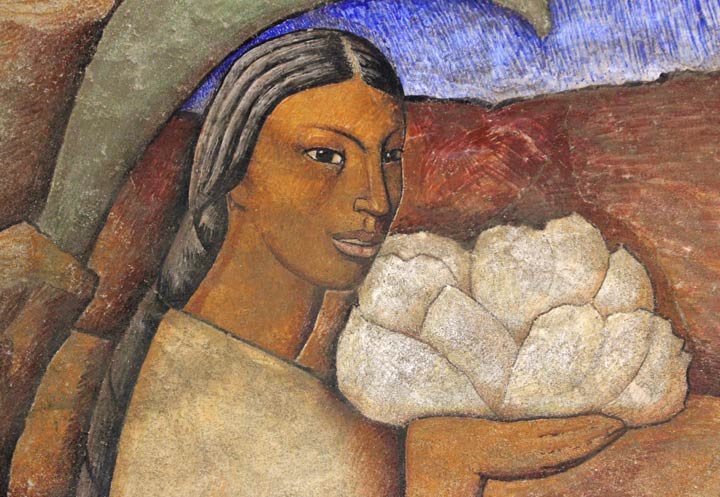

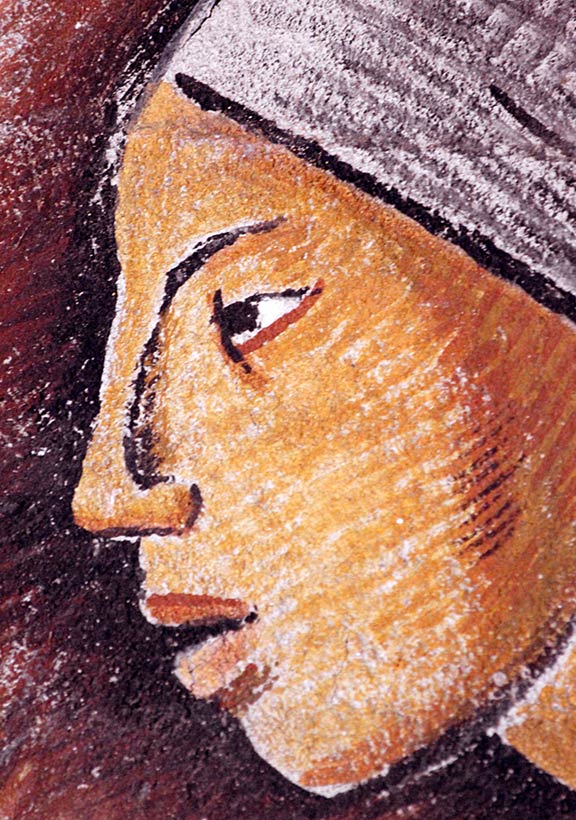

In 1946 Scripps College commissioned Martínez to paint The Flower Vendors mural. It is a tragedy that in the middle of working on the project, Martínez died on November 8, 1946 at the age of 73. His wonderful mural was left unfinished, but it continues to resonate in the present. I photographed The Flower Vendors while attending the symposium, and in this article offer my photos along with my impressions of the symposium.

Amy Galpin, the curator at the Cornell Fine Arts Museum of Rollins College in Winter Park, Florida, presented her talk Making Religion Modern: Alfredo Ramos Martínez and his Contemporaries. A devout Catholic, Martínez created a number of works that were of a religious nature; Galpin focused on those works.

Martínez returned to Christian themes in his paintings and drawings again and again, but the topic was usually bound to the artist’s ideas concerning social justice for the poor and downtrodden. This point was driven home when Galpin projected a slide of Martínez’ 1939 tempera and ink drawing, The Bondage of War.

The Bondage of War depicts a Mexican Indian man tied-up with heavy ropes that hold him immobile, a length of rope tightly twisting around his neck slowly strangles him. The tormented campesino stands in for humanity as a whole; it is 1939 and the winds of war have reached cyclone proportions. Nazi Germany, Fascist Italy, and Imperial Japan have already formed an alliance. In 1939 the Nazis seize Czechoslovakia, Spain falls to the fascist army of General Franco, and the Nazis invade Poland. Martínez made his antiwar drawing on a copy of the Los Angeles Times, the banal printed columns and ads from the paper bleeding through the drawing of the campesino. To this work Ms. Galpin juxtaposed a slide projection of an artwork Martínez created depicting the suffering Christ bound in ropes – the similarity between the two artworks was striking. Both were closely cropped minimalist portraits done in limited color schemes, but more importantly, both artworks spoke powerfully about agony and redemption.

Ms. Galpin placed Martínez and his religious works in the broader context of modernist art. She projected slides of artworks made by other modernists who had created religious art in the Christian tradition; Jean Charlot (whose works appear in the PMCA Martínez exhibit), Edith Catlin Phelps (Wayside Madonna), Ivan Albright (his hallucinogenic The Temptation of St. Anthony), and Charles White (Spiritual). There are many other example of course that Galpin did not mention, the woodcuts of the German Expressionist Karl Schmidt Rottluff come to mind (Head of Christ 1918). It was a refreshing take on modernism; three weeks prior to attending the Martínez symposium I had attended TRAC 2014, where conservative keynote speaker Roger Scruton scorned modernism for destroying the sacred in art and replacing it with the profane.

Ms. Galpin concluded her remarks by saying that the more political artists like Rivera, Siqueiros, Orozco, etc., ultimately saw Martínez as one of their own because of the deep humanism and love of the common people that he expressed in his paintings and drawings.

In her presentation, Conserving Alfredo Ramos Martínez’ The Flower Vendors, art conservator Aneta Zebala talked about the meticulous process of restoring and conserving The Flower Vendors mural located in the Margaret Fowler Garden on the Scripps College campus. Trained in the restoration of wall and easel paintings at the Academy of Fine Arts in Krakow, Poland, Ms. Zebala was also part of a collaborative team that worked with the Getty Conservation Institute in preserving the Siqueiros América Tropical mural located on L.A.’s Olvera Street.

In 1994 Zebala and her associates found The Flower Vendors in poor shape. The mural was suffering from water damage, which not only caused the paint to bleach out in certain areas of the painting, but gave rise to the build-up of salt deposits that further eroded paint pigments; paint was flaking off throughout the mural. Incredibly, ivy from the garden had crept over the mural’s surface, and the plants sank thousands of tiny roots into the outdoor mural. Zebala recounted how difficult it was to remove the roots and restore the damage they caused. Vandals had also painted graffiti on a certain area of the mural, increasing the headaches of restoration and preservation that Ms. Zebala and her team faced.

Zebala revealed some important facts about how The Flower Vendors mural was produced. The painting was created using the traditional Italian fresco method.

On the wall to be painted, skilled plasterers first applied a rough layer of lime plaster mixed with large granules of sand. Called the “arriccio,” this layer was allowed to dry.

Next, the artist drew a very rough sketch or guide on the arriccio called the “sinopia,” named after the dark red earth pigment used to paint it. The sinopia helped in guiding the layering on of the last coat of fine plaster, the “intonaco.” The intonaco was laid on in small patches, just the amount that an artist could finish painting on in one work session. The artist would paint onto the wet intonaco layer with water-based pigment, remembering the outlines of the sinopia hidden beneath the fresh intonaco. When the plaster and pigment set and dried, the painting became permanent.

Over the years fresco painting developed a slightly more sophisticated technique that abandoned the sinopia as a guide for the artist. In this method, once the fine intonaco layer was layered over the rough arriccio, a life-sized drawing on paper – the “cartoon” – that had its outlines perforated with a needle, was placed over the wet intonaco and pounced with a small sack filled with charcoal dust. When the cartoon was removed, the outlines of the drawing were left on the wet plaster and the artist could begin painting. This method allowed for complex drawings to be transferred to the wet plaster; the artist no longer had to memorize what was beneath the intonaco in order to proceed, instead the cartoon tracing left a completely worked out line drawing to be painted over and refined.

What Aneta Zebala revealed was that Alfredo Ramos Martínez used the earlier method of fresco painting, that is, he used a sinopia as his rough guide in painting his mural. Once the last layer of fine plaster was placed over the sinopia, the artist had to remember what the drawing looked like; he was in essence flying blind. In all of her restoration and preservation work on the mural, Ms. Zebala found no evidence that a pounced cartoon was used to provide Martínez with a guide. He simply painted freehand onto the wet plaster. Since Martínez’ mural was left unfinished, one can see the rough layers of arriccio and sinopia sketches in one section of the mural, while in other sections it is easy to see the intonaco with semi or near finished paintings. It is sad that The Flower Vendors mural was unfinished, but it has left us with an amazing example of how a traditional fresco mural is painted.

The high-quality restoration and preservation work carried out on The Flower Vendors brought the mural to life. When contemplating the fresco, one tends to forget that it is unfinished.

Mary Goodwin, an Associate Professor of Art History at the University of Alaska in Fairbanks, gave a talk titled, Printmaking in Los Angeles and the Role of Maria Sodi de Ramos Martínez. Ms. Goodwin revealed some hitherto unknown historical facts, even to those stalwart veterans of the Los Angeles arts community.

It all began with a Martínez “painting” that hung in the Goodwin household when Mary was a young girl. She became perplexed when she saw the exact same work in the home of relatives. She eventually discovered that the work was not a painting at all, but a serigraph – a silkscreen print; still, it was assumed that the print had been created by Alfredo Ramos Martínez. Fast forward to Ms. Goodwin as an adult with a B.A. in aesthetic studies from UC Santa Cruz and an M.A. and Ph.D. in art history from Boston University. In her research she made some startling discoveries regarding the Martínez silkscreen.

It is well known, at least to those who have studied the works of Alfredo Ramos Martínez, that his wife, Maria Sodi de Ramos Martínez, was a fierce champion of her husband’s works. After Alfredo died in 1946, Maria continued to organize exhibits of his works. To help continue and expand the legacy of Alfredo, Maria printed 7 separate silkscreen print editions that were reproductions of selected works by her husband. Printed by Maria in the garage of her Los Angeles home between the years 1947 and 1951, the most complex prints utilized 62 different colors – meaning 62 different screen stencils had to be hand-painted. Maria signed the works with her own name; some of the prints had a price as low as $35.00.

But the story did not end there. Maria learned how to produce silkscreen prints from the artist credited with originating silkscreen as a fine art medium, Guy Maccoy (1904-1981). In 1933 while working in New York with the Work Progress Administration (WPA), Maccoy began developing the screen printing process, earning him the moniker “Father of the Serigraph.” In 1938 Maccoy had the nation’s first one-person show of silkscreen prints. In 1945 Maccoy moved to Los Angeles, California. He taught Maria Martínez his technique of painting directly upon a stretched screen with lithographers tusche and water based glue in order to create a stencil.

Years later Maria Martínez would teach Corita Kent, a Sister of the Immaculate Heart of Mary, how to produce serigraphs. Running the art department at L.A.’s Immaculate Heart College until 1968, Corita became a dynamic force in the activist arts, and her anti-Vietnam war and social justice posters became ubiquitous in the counterculture of the 1960s and 1970s. In turn, Corita taught her student Sister Karen Boccalero the skills taught to her by Maria Martínez. In 1970, Boccalero became a co-founder of L.A.’s Self Help Graphics, which continues to be a cornerstone institution for the national Chicano art movement.

Mary Goodwin closed her talk by commenting on how we need to continue “teasing out” these multifaceted stories in order to build a complete understanding of history. The synchronicity between Guy Maccoy, Maria Martínez, Corita Kent, and Karen Boccalero was based on a common vision of art being made accessible to large numbers of working people. Muralism has always been a vital component to that aspiration, with The Flower Vendors by Alfredo Ramos Martínez remaining a superlative model of the art.

As a long time follower of Chicano art history, especially in my hometown city of Los Angeles, it was absolutely revelatory to find a direct link between Ramos Martínez, and the Chicano art movement, through the serigraphy of his wife Maria Martínez. Furthermore, it makes it even more historically important that the PMCA’s current exhibit of Picturing Mexico: Alfredo Ramos Martínez in California is in conjunction with the exhibit Serigrafía, an overview of Chicano/Latino silkscreen art from the 1970s to the present that also includes one of my prints. A more fitting combination could not be had, as we now have learned from Ms. Goodwin’s research.

The two exhibits run until April 20, 2014. Museum admission is $7, free for PMCA members. The museum is located at: 490 East Union Street, Pasadena, CA 91101. Web: pmcaonline.org

— // —

Read more about Martínez at, Alfredo Ramos Martínez: Picturing Mexico.