Siqueiros: América Tropical Press Conference

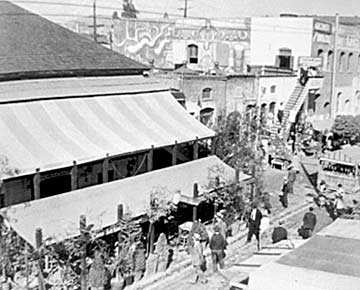

The Mexican Muralist David Alfaro Siqueiros completed his second Los Angeles mural, América Tropical, in 1932. Created on the rooftop of the Italian Hall building located on the city’s historic Olvera Street, the mural was formally presented to the public in an official unveiling that took place on the evening of October 9, 1932. Within six months the portion of the mural visible from the street was whitewashed by conservative city authorities because of the artwork’s political message – a searing attack on U.S. imperialism. Inside of a year the authorities obliterated the entire mural with whitewash. América Tropical has remained hidden from public view for the last 77 years – but that is about to change.

By invitation I attended the March 31, 2010, event at the Los Angeles Central Library’s Taper Auditorium, heralding the progress of the future David Alfaro Siqueiros América Tropical Mural And Interpretive Center. Sponsored by Amigos de Siqueiros, the city government of Los Angeles, and the Getty Conservation Institute, the event was the first opportunity for the public to learn the details regarding the upcoming $9 million visitor center – which is on the verge of being constructed. The event was attended by some 200 people, including foreign dignitaries, elected officials, museum staff, arts professionals, and members of the media. The program lasted nearly two hours and included several informative Powerpoint presentations about the future center.

The moderator for the evening was Armando Vazquez Ramos, co-chair of Amigos de Siqueiros, which has as its mission the conservation, protection, and promotion of the América Tropical mural.

Ramos briefly introduced a number of VIP’s in attendance, such as the Secretary of Culture for Mexico City, Elena Cepeda; the Director of the Getty Conservation Institute, Timothy P. Whalen; the Executive Director and Chief Curator at the Autry National Center’s Museum of the American West, Jonathan Spaulding; as well as a delegation of staff members from the Santa Barbara Museum of Art, which houses the only intact U.S. mural by Siqueiros – Portrait of Mexico Today: 1932. After opening remarks by Ramos and fellow co-chair of Amigos, Dalila Sotelo, the two introduced Father Richard Estrada of Our Lady Queen of Angels Catholic Church in Los Angeles, who gave a benediction that blessed Siqueiros and all artists who work for the people and social justice.

Los Angeles Mayor Antonio Villaraigosa was scheduled to address the gathering but at the last minute could not attend. Consequently, following Father Estrada’s blessing, a representative spoke on the Mayor’s behalf. After assuring the audience of the Mayor’s full commitment to the Siqueiros mural project, she promised those gathered that by “the end of this summer, there will be a groundbreaking ceremony to start this project.”

Here I must note a statement that the Getty’s Timothy P. Whalen gave the press at the event, explaining that once there is a groundbreaking, it will take 18 to 24 months to complete the construction of the center, now scheduled to be finished by 2013.

The Mayor’s representative was followed by L.A. Councilmember José Luis Huizar of the 14th District, who delivered an address further confirming the city government’s devotion to seeing the Siqueiros mural project completed. He told those gathered that “We have to uncover this beautiful mural and show it to the world.” Following Councilmember Huizar was California State Assembly Member, Kevin De León, of the 45th Assembly District of Los Angeles.

Assemblyman De León told a humorous but heartfelt story about how he came to discover the América Tropical mural. Mr. De León has a friend with access to the Italian Hall, the building on Olvera Street where Siqueiros painted his mural on the exterior of the second floor rooftop. The friend kept telling De León about the rooftop mural by Siqueiros, but the Assemblyman simply did not believe the story. One day that friend arranged to have De León visit the Italian Hall, and upon entering the building and surveying the dust, disrepair, and general disorder of the historic site (which is presently closed to the public), De León became convinced his friend was playing a practical joke on him – until the two made their way to the rooftop.

When De León set his eyes upon the mural that he never knew existed, he was, in his own words, “blown away.” He described his discovery as a life changing experience, and ended his address by vowing to do everything within his means to see the Siqueiros Mural And Interpretive Center brought to completion. “América Tropical,” De León said “is a treasure we must preserve.”

Assemblyman De León’s presentation wrapped up the formal statements issued by members of the city’s government, and the audience then began to receive details on the progress of the Mural And Interpretive Center project. I am certain that, as someone who has followed the story of América Tropical since the late 1960s, I was not alone in feeling a sense of astonishment that at long last the mural was actually being brought back to life; that its regeneration was backed by the City of Los Angeles and the prestigious Getty museum, and that the mural would rightly take its place as a major historic site for L.A. and for the international arts community.

Leslie Rainer, a conservator at the Getty Museum’s Getty Conservation Institute (GCI), was introduced, and her Powerpoint presentation ran through the history of the mural, with a focus on the GCI’s involvement in the mural’s preservation, which began in earnest in 1989. Rainer gave a step by step account of GCI efforts over the years; seismic retrofitting of the wall on which the masterwork is painted, the installment of rigid protection panels over the mural to shield it from the elements, the stabilizing of the mural with protective chemicals, and the analysis of the paints Siqueiros used in creating his mural. Here the artist left conservators a vexing challenge, and while Ms. Rainer did not go into those details, I will share the particulars as I understand them.

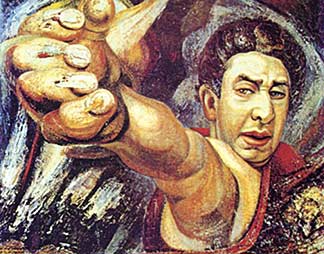

In his desire to use the most revolutionary techniques and materials, Siqueiros abandoned the time tested fresco mural technique of painting with water-based pigments on fresh lime plaster – the method fellow muralist Diego Rivera utilized. Siqueiros instead created his mural by painting on cement with automobile lacquer paint applied with a spray gun and brushes. Using a compressed air spray gun powered by a generator was something only Siqueiros had done in his previous works, likewise his use of pyroxylin, the aforementioned auto lacquer paint. A nitrocellulose based lacquer once used to paint cars; pyroxylin was the artist’s favored paint because of its intense pigmentation, rapid drying time, and tendency to produce startling effects when different colors were allowed to flow together.

While previous works by Siqueiros were created on masonite or other stable grounds given an underpainting of gray pyroxylin, América Tropical was painted by direct application of pyroxylin on a single layer of cement – and the two did not bond well; the pyroxylin immediately fixed on the cement surface instead of penetrating it. After some time the pyroxylin began cracking and pulling away from the cement, a process exacerbated by the whitewash coating. GCI conservators have exerted a great amount of energy in successfully arresting the degradation of the mural. They determined that a complete full-color restoration of the original mural would only destroy the integrity of the work, so it was decided to preserve the mural as it is – a ghost of its former appearance.

Ms. Rainer went on to recount how América Tropical became almost entirely lost to memory, until the late 1960s Chicano Power movement in L.A. rediscovered Siqueiros and his mural – which in large part inspired the Chicano Arts Movement. In 1968 the mural came to public attention simply because the whitewash had begun to peel off, exposing tantalizing bits of the long forgotten artwork. Rainer told how in that year Shifra Goldman made photographic documentation of the devastated mural, kicking off a campaign to preserve América Tropical as well as providing impetus to the Chicano Arts Movement. Ms. Goldman has been a pioneer in the study of modern Latin American art, and it is hard to imagine this area of research without her scholarship and fortitude.

After Ms. Rainer’s presentation, Gwynne Pugh, the principal and co-founder of Pugh + Scarpa Architects, gave a Powerpoint presentation that was a project overview on architectural matters.

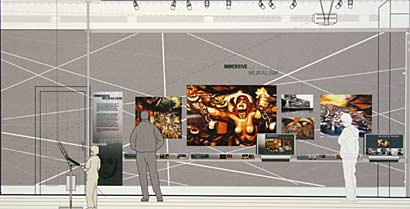

Pugh walked the audience through the floor plans and blueprints for the Interpretive Center, providing great insight into its engineering and structural designs. The center’s two thousand square feet of galleries will include a rooftop viewing platform, where people will be able to view the mural. Following Mr. Pugh’s talk was Thomas Hartman’s presentation. President of IQ Magic, a firm involved in interactive exhibits and displays for museums, Mr. Hartman lectured on a range of topics related to the mural. He described how the various rooms in the Mural Interpretive Center will look and function, using his Powerpoint display to provide digital graphics and artist’s concept drawings to illustrate his firm’s vision and goals for the center.

Hartman described the two-story center as spacious and well lit by natural sunlight, with hand worked materials like field stone and yellow cedar wood commonly used throughout the building. He disclosed that the entryway to the center will be ceremonial in nature, giving the public a good idea of what the center contains, even if the upper floors are closed. A large photograph of Siqueiros will welcome visitors, and when they step into the ground floor entry room they will be faced with multiple wall plaques of text, artworks, and photographs that explain the museum’s concept and purpose. Not a true museum that displays original art and artifacts, the Mural Interpretive Center will instead provide educational and interactive displays that will inform, educate, and engage a wide and varied audience.

Mr. Hartman described the various multi-media displays that will be central to the Mural Interpretive Center experience; projectors that will throw a 30 foot long full-color reproduction of the mural on an internal gallery wall, where that digital projection will be supplemented by other, smaller projections; details of the mural, photographs of the artist at work, and other images. Some displays will incorporate digital audio systems and speakers that when touched, will transmit audio files of spoken histories and narratives pertaining to the mural’s history.

Likewise, 30 inch flat screen computer monitors placed throughout the center will offer all types of information to viewers. Hartman emphasized the flexible nature of these proposed displays, noting that as technologies change and expand, older displays will easily be rotated out and replaced with updated versions.

Mr. Hartman’s description of the rooftop viewing platform was most engrossing. Ultimately, visitors to the center will find themselves led to the roof, where they will gather on a special 240 square foot viewing platform placed adjacent to, but some 125 feet from the actual mural.

That space will protect the mural from those who will want to touch it, but it will also afford a clear and unobstructed full view of the mural. A specially designed canopy will stretch out above the mural for some thirty feet, protecting it from the harsh L.A. sun, and large perforated copper side screens will also serve the same purpose. The platform is designed to accommodate a steady stream of hundreds of viewers, who will be able to reach the rooftop by stairs or elevator.

In closing, Mr. Hartman invited those gathered to imagine what the original October 9, 1932 unveiling ceremony must have been like. It was, as he noted, “the event of the season,” and much of the city’s intellectual elites were in attendance; writers, artists, photographers, political activists – city politicians and mainstream media as well. Also in attendance that evening were members of the “Bloc of Painters,” those American artists who had assisted Siqueiros in the painting of América Tropical and his first L.A. mural, Mitin Obrero (“Worker’s Meeting” – painted at L.A.’s Chouinard School of Art in 1932). The Bloc included some twenty painters, including the likes of Millard Owen Sheets, Philip Guston, Barse Miller, Phil Paradise, Fletcher Martin, Harold Lehman, Reuben Kadish, and Luis Arenal. Hartman indicated that the accounts of some of the Bloc painters would be included in the center’s interactive displays.

In addition, Mr. Hartman mentioned that Dean Cornwell attended the public unveiling of América Tropical. Cornwell would be responsible for painting the 1933 monolithic mural series, California History, still located on the second floor interior rotunda of L.A.’s magnificent Central Library. Cornwell and Siqueiros both painted murals in L.A. that told the history of the Americas; with América Tropical Siqueiros told a story of imperialist expansion, colonialism, and resistance – Cornwell on the other hand painted a mural that extolled a benevolent and civilizing Western colonialism. The two visions could not have been further apart, needless to say Cornwell’s mural was enthusiastically supported by L.A.’s upstanding citizens and civic leaders, while Siqueiros’ work received a coat of whitewash. In truth the two artists had genial relations, in fact, Cornwell not only helped sponsor the Siqueiros mural, he assisted in its painting (In 1994 L.A. Times art critic Christopher Knight wrote about the two murals in his article, Two Murals, Two Histories. You can see a portion of Cornwell’s Central Library mural here).

The closing remarks of the program were given by Gregorio Luke, the former Director of the Museum of Latin American Art (MOLAA) in Long Beach and currently the Executive Director of Amigos De Siqueiros. I have had my disagreements with Mr. Luke, and I made them public in June of 2007 when I wrote Chicano Artists Need Not Apply, a critique excoriating Luke for his “protracted refusal to exhibit or otherwise collaborate with Chicano/Mexican American artists” at MOLAA. Perhaps Luke has changed his ideas regarding Chicano artists, I am not certain, but his remarks at the L.A. Central Library’s Mark Taper Auditorium indicated an enlightened position – in fact, I found his lecture inspiring. Luke revealed an obvious passion for the works of Siqueiros, and he spoke with the animated gestures and energy of an old fashioned orator; he can really be quite engaging and persuasive, so Amigos De Siqueiros will no doubt benefit from his leadership.

Aside from his grand rhetoric in praise of maestro Siqueiros, Luke let loose a few salient remarks I found of great consequence. He divulged that he has been approached by Chicano artists who made it known that in part, they pursued art because of Siqueiros’ influence. I would place myself amongst this group. I discovered Siqueiros in 1968 when I was fifteen years old, and I do not hesitate to say that without his influence I would have been a very different artist. Luke also commended Siqueiros for his revolutionary activism on behalf of the downtrodden, noting that the artist made no distinction between painting and his political acts, to Siqueiros the two were seamlessly integrated. Observing that Siqueiros’ example provides today’s artists with a way forward, Luke chastised those who only want to “paint like the old masters of the past,” but he reserved his ire for today’s detached and indifferent crowd of postmodernists, “who are imprisoned by their own limitations” and “want to be so avant-garde that they become irrelevant to the people.”

Mr. Luke ended with a powerful assertion regarding the soon to be reborn América Tropical mural: “We will reverse an act of censorship, and provide inspiration for another, future revolution.” With that the event ended, but what transpired that evening will provide food for thought for months to come – at least until that promised end of summer groundbreaking for the David Alfaro Siqueiros América Tropical Mural And Interpretive Center.

I admit feeling an amused but wary skepticism regarding the whole affair. I can only imagine what Siqueiros, the implacable communist militant, would make of his legacy being blessed by a Catholic Father, warmly embraced by U.S. politicians, and enshrined by a major Yankee art museum. Oh, the contradictions! If Frida Kahlo had painted a mural in Los Angeles during the 1930s, the L.A. city government would have long ago wrapped it in an edifice designed by Frank Gehry. “Gringolandia” might wish to give Siqueiros the Frida Kahlo treatment, i.e., to turn him into a chic handbag or a trendy coffee table book, but the art of Siqueiros may prove difficult to commodify, since it directly speaks the urgent and uncompromising language of revolution. His works continue to be controversial, and goodness knows how we need a contentious and oppositional force in today’s art world – not to mention the rest of society.

I leave you with the inspired words of news reporter Don Ryan, who covered the original 1932 official unveiling of América Tropical in the October 11, 1932 edition of the L.A. Illustrated Daily News, Ryan wrote of that ceremony;

“This night that we are living seems to be fifty to one hundred years in the future. The artist Siqueiros, whom the federal authorities seem so anxious to deport, is without doubt a dangerous type; dangerous for all the snarling and pusillanimous spectators and retailers in art and life. The federal agents justly claim that his art is propaganda, for when the youth confront this gigantic dynamo that pounds in the night under the rain, or clamors boldly when the brilliant sun of midday shines in the plaza, they will possibly find it the inspiration to rise in rebellion in future revolution, in art and in life, exclaiming; ‘Off the road conservatives and old ones, here comes the future!'”