American Stories: Paintings of Everyday Life

Celebrated American paintings were presented at New York’s Metropolitan Museum of Art in an exhibition titled American Stories: Paintings of Everyday Life, 1765-1915. The exhibit was comprised of 103 paintings that depicted the American experience from the colonial period to the Gilded Age of the late 19th century.

On display were iconic canvases by the likes of John Singleton Copley, Winslow Homer, Thomas Eakins, Mary Cassatt, John Singer Sargent, John Sloan, and George Bellows, along with artists whose names are unfamiliar to most, but whose works have left an impact on the American consciousness. The exhibit ran from Oct. 2009 to Jan. 2010.

The Metropolitan’s publishing house released an exhibit catalog that features many works not included in the show. People on the West coast of the U.S. can see the Met’s survey of American art at the Los Angeles County Museum of Art (LACMA), where the show opened on February 28, 2010 for a four-month run.

The exhibit is divided into four categories presenting a timeline of the nation’s development; Inventing American Stories: 1765-1830, Stories for the Public: 1830-1860, Stories of War and Reconciliation: 1860-1877, and Cosmopolitan and Candid Stories: 1877-1915.

The Met’s conception of the nation’s history sweeping from the East to the West coast was meekly “corrected” by LACMA adding a fifth category; paintings depicting the Spanish, Mexican, and Chinese influence on the history of California, but this section of the exhibit seemed but an afterthought.

LACMA reduced the number of paintings the Met originally had on display by around 20, and swapped out paintings from the Met’s collection for works found in LACMA’s collection, for instance, the Met initially included Thomas Eakins’ Swimming (1885), whereas LACMA replaced it with the artist’s Wrestlers (1899).

The exhibit is important for a number of reasons, not all of them related to the progress of American art. The show gives an overview of the nation’s growth, presenting a wide look at the people and forces that shaped the country. Artists in the exhibit frequently brought up questions of class, race, and gender, unconsciously or not, and to see America’s changing political landscape chronicled by artists is just one of the fascinating aspects of the show.

Today’s Americans will hardly be able to recognize the country and people depicted in American Stories; the transformation of American society from 1765 to the present having been truly astonishing in scope.

Existing U.S. culture with its digital communications and amusements, “reality” television shows, and celebrity worship, bears little if any resemblance to the country as it was from 1765 to 1915; yet, some things never change. Thoughtful viewers will be compelled to ask the questions, “What does it mean to be an American?” and “Where are Americans going as a people?”

I attended the LACMA exhibit on March 1, 2010, and recommend it to others. There are simply too many fabulous artists and paintings in the show to write about, so I proffer the following opinions regarding just a few of the works found in the show.

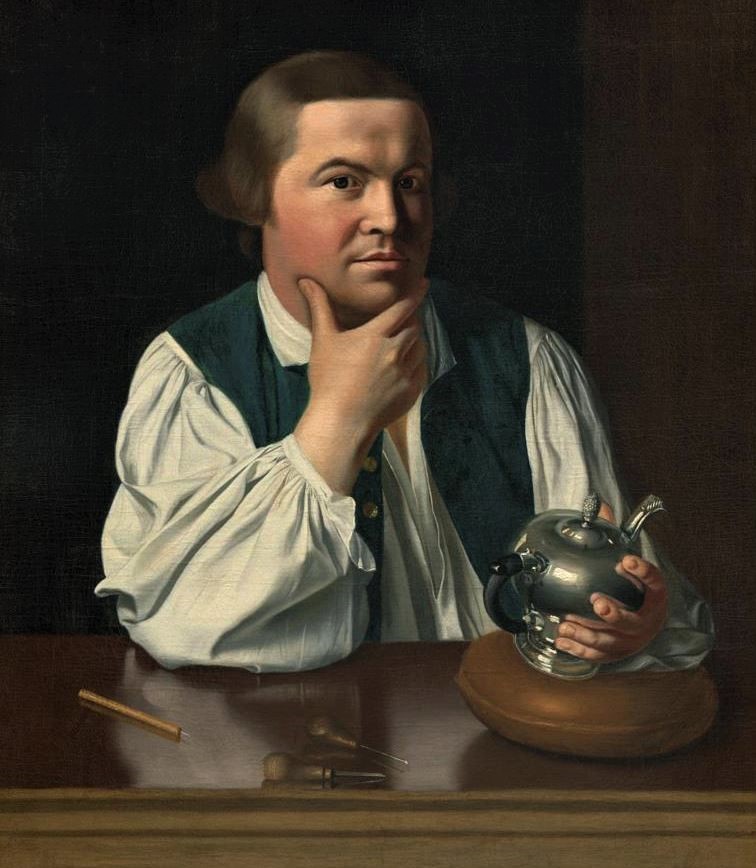

The first painting to greet the viewer is Paul Revere by John Singleton Copley (1738-1815). His iconic 1768 portrait of the Boston silversmith, who would come to play a major role in the American Revolution, is a remarkable work of art, partly because the artist was self-taught at a time when there was not a single art school or museum in the colonies.

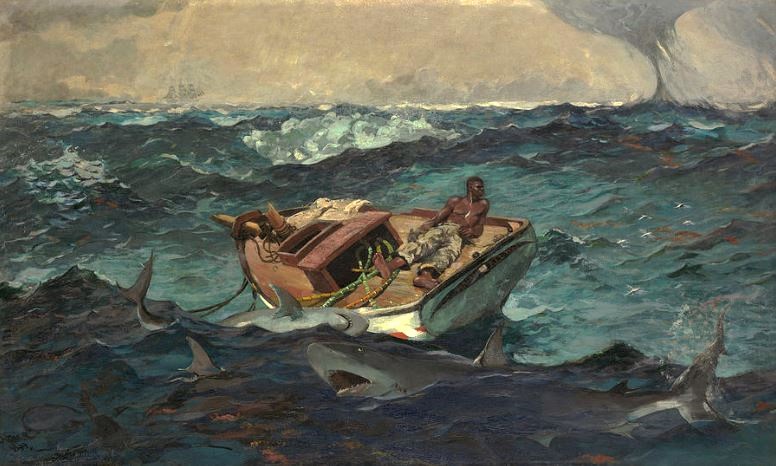

The jolt of standing in front of Copley’s flawlessly realistic painting of the American revolutionary is repeated when seeing that the room in which it is hung also holds other marvelous canvasses; The Cup of Tea by Mary Cassatt, Chinese Restaurant by John Sloan, The Breakfast by William McGregor Paxton, The Gulf Stream by Winslow Homer, Watson and the Shark by John Singleton Copley, and Eel Spearing at Setauket by William Sidney Mount. That African Americans are central characters in three of these paintings is but an introduction to the complicated racial dynamics in the U.S. that serves as a subtext for much of the exhibit.

In Copley’s Watson and the Shark (1778), it is a black man that holds a rope lifeline to the imperiled Watson, who is being attacked by a shark in open water. The artist put the black sailor at the apex of a triangular composition in order to draw the eye directly towards him; he is also portrayed as an equal to all the others, a remarkable narrative for a canvas painted when America held African people in bondage.

Painted 16 years before the American Civil War, Mount’s Eel Spearing at Setauket (1845) has as its focus a black slave woman at the bow of a small boat teaching a young white boy how to catch eels. While the woman is obviously in control, she is also a slave. Homer’s The Gulf Stream could be construed as an allegorical painting regarding the status of blacks in America in 1899, 38 years after the close of the Civil War.

The canvas depicts a black man in a small wrecked sailboat cast adrift on a stormy sea filled with sharks. I could write lengthy essays about each of these extraordinary paintings, but for the sake of brevity I shall restrict my remarks to John Singleton Copley’s Revere.

Born in Boston, Massachusetts, Copley had no formal training in art, but his stepfather was an engraver and portrait painter who undoubtedly tutored the precocious teenager for the three years they lived together. By the time Copley was fifteen he was known for producing impressive oil portraits of notables in his community, and that reputation, not to mention his technical skill as a painter, grew considerably. He was thirty when he painted Paul Revere (1735-1818).

When Revere sat for Copley he had not yet carried out the acts that would make him famous, like his illustrious April 18, 1775 Midnight Ride from Boston to Lexington to warn patriots of British troop movements.

He was nevertheless deeply involved in the Sons of Liberty, that underground organization of patriots whose “no taxation without representation” slogan came to epitomize the anti-colonial struggle. Five years after Copley painted Revere, the Sons of Liberty initiated the legendary Boston Tea Party of Dec. 16, 1773, when patriots, including Revere, seized three ships in Boston Harbor in order to dump the cargo of British tea overboard in an act of protest against British taxation.

That fact is not insignificant when considering the portrait of Revere, since Copley’s father-in-law was the merchant that had his British-consigned tea tossed overboard during the Tea Party! The issue of British taxation went back to 1767, a year before Copley painted Revere, when the British Parliament imposed heavy new taxes on tea in the colonies. Given that evidence, Copley’s painting takes on new meaning.

Revere had Copley paint him as a master craftsman in the silversmith trade, he was after all one of the most famous silversmiths in colonial America. On the mahogany table at which Revere sat, you can see his silversmith tools set out before him, and he had himself pictured holding a silver teapot. It has generally been accepted that Copley’s painting of Revere is simply a portrait of a successful artisan, but I think there is ample evidence to suggest otherwise.

One must take into account that at the time of the painting’s creation, people living in the thirteen colonies were entering a period of intense political conflict that would ultimately lead to revolutionary war. Viewed in that context, it is incorrect to see the portrait merely as an expression of Revere being proud of his profession, rather, it appears he meant his portrait as a political statement.

An outspoken radical, Revere was no doubt infuriated by the 1767 British tax on tea, and so it was probable that by having himself painted holding a teapot, he was challenging viewers over British rule. Revere stares directly at the viewer as if to ask, “Which side are you on?”

It was also unusual for a gentleman to have himself painted wearing anything other than his finest frock coat, yet Revere had himself depicted wearing an open sleeveless waistcoat (the undergarment worn beneath a fine coat) and a linen shirt, which at the time was a form of “undress” appropriate only for hard work or relaxing at home in private.

The British controlled the economy of the colonies through the importation of goods and by imposing taxes. As the anti-colonial movement gained strength, patriots found multiple ways of resisting British hegemony, such as boycotting imported goods. When the colonists began producing linen as an act of resistance, those using imported British linen were isolated as Tories, conservative supporters of British rule. By having himself portrayed wearing a billowing shirt of American-spun linen, Revere was making a statement in favor of independence; the shirt was not so much a symbol of being a craftsman as it was an affirmation of revolutionary politics.

While Revere’s linen shirt and teapot were more than likely politically charged props, Copley had no interest in political matters, besides, his family members were Loyalists devoted to the British Crown. In a 1770 letter Copley wrote to Benjamin West (an American-born artist who moved to England and became a painter to the court of King George III in 1772), he flatly stated that he was “desirous of avoiding every imputation of party spirit. Political contests being neither pleasing to an artist or advantageous to the art itself.”

Though he helped establish American painting and created portraits of prominent American patriots, Copley did not have a passion for independence. His relationship to Revere, as well as his attitude towards the anti-colonial movement, is indicative of the complicated human drama that occurred during the revolution. Copley left the colonies for London in 1773, a year after the Boston Tea Party… never to return to America.

Another notable artist from the Revolutionary War period whose works are included in the exhibit is Charles Willson Peale (1741-1827). A fiery radical and member of the Sons of Liberty, Peale created portraits of many leaders involved in the War of Independence, John Adams, Thomas Jefferson, George Washington, John Hancock, and Alexander Hamilton to name but a few. In 1765 Peale met the artist John Singleton Copley, and studied in his Boston studio for a time before traveling to London in 1770 for two years of formal training under the tutelage of Benjamin West. Upon return to the colonies, Peale settled in Philadelphia, and in 1776 he joined the Continental Army to wage war against the British Empire.

After the successful War of Independence, Peale refocused his energies on the arts and sciences. In 1782 he opened the very first art gallery in the United States, and in 1786 he established the nation’s very first museum, the Peale Museum, which was given to the exposition of paintings and natural history. There are two paintings by Peale in the LACMA exhibit, a 1788 double portrait of the merchant Benjamin Laming and his wife Eleanor, and the 1805 Exhumation of the Mastodon, whereupon Peale recounted his having discovered and excavated a prehistoric mastodon skeleton in New York, painting the scene for posterity.

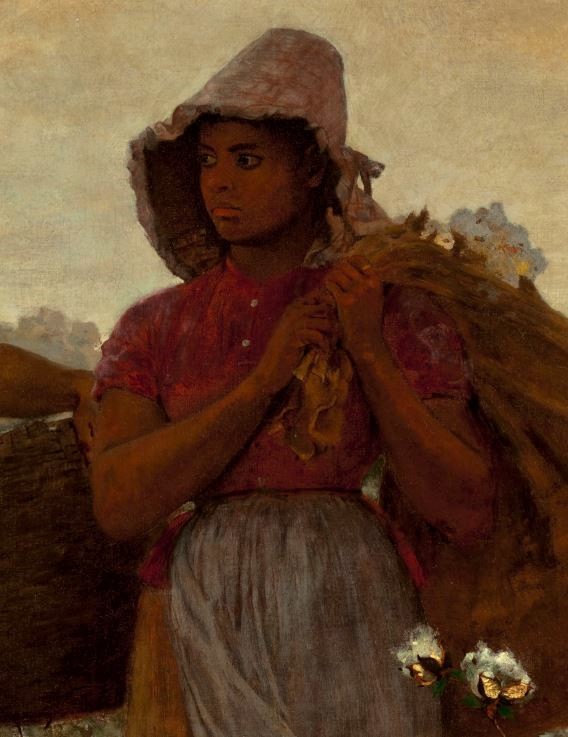

Skipping ahead to mid-point in the exhibit there is a collection of splendid canvasses by Winslow Homer, these are aside from his painting in the exhibit’s opening room. Of the handful of works arranged on their own wall under the Stories of War and Reconciliation section of the show, two took my breath away, The Veteran in a New Field and The Cotton Pickers.

Created in the aftermath of the U.S. Civil War (1861-1865) and the assassination of President Abraham Lincoln (April 14, 1865), The Veteran in a New Field (1865), depicts a former soldier hard at work harvesting wheat, his Union army jacket cast off and laying in the field at the picture’s lower-right corner.

The ex-combatant swings his scythe into the tall wheat as if he were the grim reaper, the fallen wheat symbolizing the massive numbers of deaths from the war, including the nation’s chief executive. Some 620,000 soldiers from the Confederate and Union armies perished in the conflagration, along with an undetermined number of civilians. By contrast, around 416,000 U.S. soldiers were killed in WWII. It is not hard to imagine the impact this painting had on Americans in 1865, but while the painting’s imagery is a metaphor for a people’s sacrifice and loss, so too is it a symbol of recuperation and redemption.

The Cotton Pickers was not included in the original Met exhibit, but since it is part of LACMA’s permanent collection, the L.A. museum wisely placed it in their showing of American Stories; luckily for the public I might add, it is one of Homer’s finest works. Painted just 11 years after the end of the Civil War, the canvas depicts two emancipated black slaves, except they are working at the same backbreaking labor they performed prior to their liberation, and likely for the same property owner.

The slave’s lament of working from before sunrise until after sunset had not changed; Homer painted the two African American women standing in a cotton field at the crack of dawn, their bags heavy with cotton picked from before daylight. The artist’s handling of the dim light of morn is awe-inspiring, but it is the expressions on the faces of the women that I found extraordinary. Far from being broken, they appear dignified and ready to step beyond dreadful circumstances. The woman in red looks positively defiant, exemplifying the spirit that would carry blacks through some very unhappy days.

The exhibit’s final category of paintings, Cosmopolitan and Candid Stories: 1877-1915, might have the most resonance for present-day viewers, since we continue to grapple with the same questions portrayed in the canvases; the evolving status of women, global expansionism, waves of immigration, industrialization and urbanization, and the predicament of the working class.

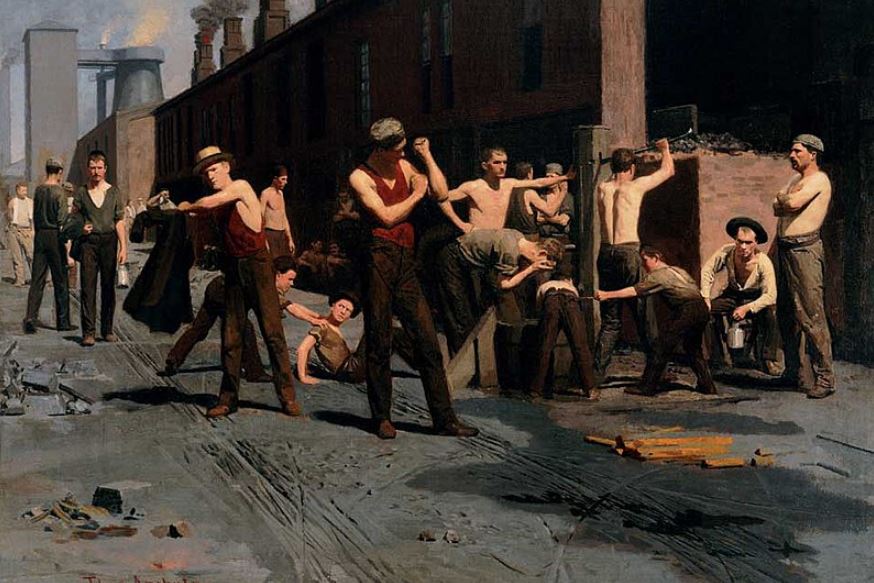

I found The Ironworkers, Noontime by Thomas Anshutz (1851-1912) to be of specific interest. Anshutz was an influential painter whose genre paintings were in great demand. Trained by Thomas Eakins (1844-1916) and William Bouguereau (1825-1905), he might at first glance seem an Academic painter, but a closer examination reveals an artist breaking with convention.

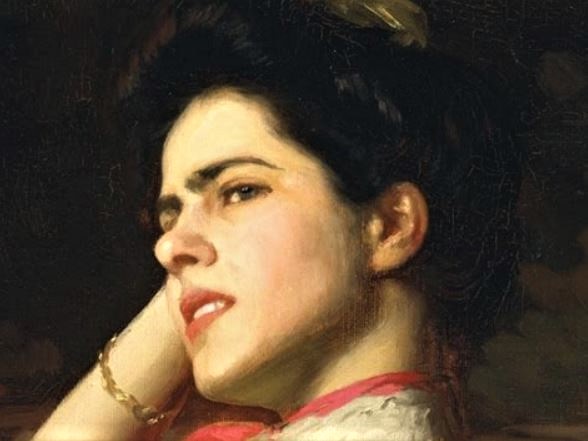

His portraits of women appear to be celebrations of American Victorianism, though a painting like A Rose depicts a women who seems a far cry from the timid and demure model of a Victorian Lady. Anshutz was a respected teacher of painting who instructed at the Pennsylvania Academy. His students included John Sloan, Everett Shinn, and William Glackens; painters who would initiate America’s first art movement, the Social Realist Ashcan school, it is their works that comprise the final group of paintings on display in American Stories.

Painted in 1880, The Ironworkers, Noontime is about as bleak a picture of America’s industrial landscape as one is likely to find. Anshutz painted men and boys who worked at a nail factory in West Virginia taking a break from their dreary work. At the time there was no such thing as an eight-hour work day.

Most American and immigrant workers labored seventy hours or more per week for extremely low wages and absolutely no benefits whatsoever. Factory work was hazardous and often injurious or fatal as safety standards were non-existent. Child labor was rampant. The burgeoning union movement was just beginning to make the eight-hour day one of its central demands.

Anshutz based his painting on sketches he made at an actual factory, and if the poses of the men seem founded on an Academic approach, overall the artwork contains important differences with Academic painting.

To begin with, the artist recorded a scene from real life, a dismal factory where laborers worked to the point of exhaustion. It was a tableau painted without romanticizing or sentimentalizing its subject; the workers were shown as simply worn-out and poverty-stricken. It was a disagreeable scene that would have sent any Academic painter to flight.

The work’s gritty realism ran counter to the saccharine idealism of Academic art. Late in life Anshutz declared his belief in socialism, and while trained by Bouguereau, he had more affinity with Robert Koehler (1850-1917), a German-born painter and fellow socialist that spent most of his career in the U.S. The two were among the first artists to depict industrialism and its impact on working people (Koehler’s work was not included in American Stories).

A prominent painter in Minneapolis, Minnesota, who also served as the director of the Minneapolis School of Fine Arts for twenty-two years, Koehler created a number of paintings that portrayed urban workers. His 1885, The Socialist, is the earliest known portrait of a working-class political agitator. Between the years 1878-1890, Germany banned socialist organizations, publications, and meetings, and as a result many German socialist leaders came to the U.S. where they addressed the growing worker’s movement in cities like New York and Chicago. Koehler’s The Socialist could have portrayed such a meeting or rally anywhere in the U.S. or Germany.

Anshutz’s The Ironworkers, Noontime was created six years before the Haymarket massacre of May 4, 1886, when violence between workers and police in Chicago led to the deaths of eight police officers and an unknown number of workers, who were on strike demanding the eight-hour day. The authorities arrested eight labor leaders and anarchist activists from Chicago’s eight-hour day movement, charging and convicting them for the murder of one of the police officers.

The U.S. labor movement was dealt a decisive blow when four of the defendants were executed, even though there was no evidence linking them to the killing of the officer. Koehler’s The Strike was painted that same year, and when his painting was shown at a spring 1886 exhibit at the National Academy of Design in New York City, a review in the April 4, 1886 edition of the New York Times referred to it as the “most significant work of this spring exhibition.”

At that very moment activists were organizing for a national strike that would bring 350,000 workers into U.S. streets to demand the eight-hour day… and the Haymarket massacre was only weeks away.

The final room in the exhibit is a showcase for the Ashcan School, with works by George Bellows, John Sloan, Everett Shinn, and William Glackens on display. Stylistically these works seem closest to our own reality; their technique, approach, and content having been influenced by the Modernist revolution. In fact New York’s Armory Show of 1913, where Americans got their first eye-opening exposure to modern art, was in part organized by Sloan; those in the Ashcan circle like George Bellows, William Glackens, Robert Henri, George Luks, and John Sloan exhibited in the groundbreaking Armory Show.

Sloan’s small oil on canvas The Picnic Grounds depicts flirtatious working class youth in a public park in New Jersey, the energetic brushwork epitomizing the best of the artist’s early works. William Glackens was a brilliant colorist who concentrated on the depiction of city life as enjoyed by middle-class layers of society. The Shoppers is one such painting, portraying a group of fashionably dressed women as they wonder through a department store, a new phenomenon in America at the time.

Everett Shinn was given to portraying life in the theater, though he created his share of canvasses depicting harsh realities on the street. In The Orchestra Pit, Shinn’s depiction of a popular vaudevillian theater in New York’s Madison Square, the artist places the viewer at the lip of the stage directly behind the orchestra pit. Of the Ashcan paintings displayed, two by George Bellows were my favorites, Cliff Dwellers and Club Night.

Club Night was from a series of artworks Bellows created from direct observation of public boxing matches, which at the time were illegal in the U.S. To avoid the law but still be able to attract paying customers, fight organizers would hold bouts at private gyms, and boxing fans gained admission by becoming “dues paying members” of the athletic clubs; competitions were held behind closed doors for members only.

Bellows frequented a squalid New York City gym across the street from his studio called Sharkey’s, where such contests were held. Disdainful of those who attended the fights, Bellows pictured them as bloody-minded bourgeois individuals slumming in poor neighborhoods.

The groups of men dressed in tuxedos in the lower right portion of the painting bear a striking resemblance to the demented characters in Francisco Goya’s A Pilgrimage of San Isidro, one of Goya’s so-called “black paintings” depicting fanatical religious zealots.

In the end the limitations of the American Stories exhibit at LACMA are overshadowed by the show’s strengths. Despite curatorial exclusions and a tendency to expound a somewhat rosy view of American history, there is still an immeasurable sense of the real, the human, and the historic in American Stories. Compared to the cynical and socially detached gimmickry of postmodern art, the paintings in American Stories exude idealism, compassion, and a deeply felt humanism.

It is regrettable that the timeline for the exhibit stops at 1915, when Modernism in the U.S. was just beginning to percolate. It would have been instructive to have included artists from the 1930s and 1940s, when the “American Scene” and “Regionalist” painters from coast to coast were in their heyday and Social Realism was the dominant aesthetic. It is unlikely that LACMA will hold such an exhibit in the future, but without a doubt I will continue to cover that era in articles yet to come.