Pressed in Time: American Prints

I cannot recommend highly enough, Pressed in Time: American Prints 1905-1950, the current exhibit at The Huntington Library in San Marino, California. Made up of 163 prints created by 82 artists during the first half of the 20th century, the show encapsulates American art as it was before the ascendancy of abstraction; an epoch when realism, meaning, compassion and technical mastery reigned supreme in the world of American art. The artists in the exhibition range from the well known to the obscure, but all the works on display are superlative examples of the art of printmaking.

The period represented by Pressed in Time, has always been of particular interest to me, as so many artists of that era made social themes the focus of their art. The term “Social Realism” was given deep humanistic meaning by American artists, and in part it was their cue that inspired me to become a contemporary realist given to social commentary. All of the artists in The Huntington’s exhibit were brilliant painters, but they were also populists whose democratic impulses led them to create multiples; prints that would help make art accessible to the masses – and it’s that concept that these prints still manage to achieve. Whether you’re interested in aesthetics, history, politics or sociology – this exhibit will speak directly to you.

One group of artists well represented by Pressed in Time, are those attached to the so-called “Ashcan School” of early twentieth century New York. These artists who brilliantly painted the city’s working poor and immigrant populations, were disparaged and mocked by hostile art critics who chastised them with the insulting label of “ashcan” – a reference to the trash bins found in urban slums. I’ve long been stirred by this particular circle of artists, and so I was thrilled beyond reason to learn that two of the Ashcan painters, John Sloan and George Bellows, had a number of prints in the exhibit. For now I’ll reserve comment on John Sloan, as I’ve had it in mind to write a long essay about him and his influence on my own work – so instead I’ll take this opportunity to gush effusively over Mr. Bellows.

I think of George Bellows as one of America’s greatest painters. Most famous for his paintings of Boxers, like the jaw-dropping Stag at Sharkey’s, Bellows had an eye for capturing the American scene. A stunning lithographic version of his famous Sharkey’s is thankfully part of the Pressed in Time exhibit. It’s the largest print in the show, but it’s not size that makes the work commanding – it’s the artist’s mastery over the art of lithography and his genius at composition that makes Sharkey’s a tour de force. But Bellows also had an eye for controversy – and after watching the exaggerated antics of a popular fundamentalist preacher at a New York City revival meeting, he made the fire and brimstone Bible thumper the subject of several mocking artworks. The Huntington exhibit includes two of these – 1923 lithographs that depict the preacher, Billy Sunday.

At the beginning of the 20th century, Sunday was the most powerful evangelical Christian preacher in the United States. A conservative Republican, Sunday was an unwavering backer of World War 1 and a supporter of Prohibition. He opposed teaching evolution and stood firm against the “godless” frivolities of dancing, reading novels, and playing cards. Sunday became incredibly wealthy delivering frenetic over-the-top sermons to millions of people across America, and it should come as no surprise that he was courted by the country’s mighty financial oligarchs and formidable politicians. Bellows’ opinion of Sunday could just as easily be applied to today’s televangelists:

“Do you know, I believe Billy Sunday is the worst thing that ever happened to America? He is death to the imagination, to spirituality, to art…. His whole purpose is to force authority against beauty. He is against freedom, he wants a religious autocracy, he is such a reactionary that he makes me an anarchist. You can see why I like to paint him and his devasting ‘saw-dust-trail.’ I want people to understand him.”

The Huntington wisely mounted in a side room of the main exhibition hall, a special exhibit that fully explains for the general public the printmaking techniques on display in the show. Presenting various stages of prints in the making as well as the tools and materials required to create the artworks, the display is of great educational value for the novice puzzled by the confusing array of print types. For instance, the process of Intaglio (etching) is put in plain words, with the description enhanced by showing actual etched copper plates. Variants like soft and hard ground etchings, engravings, Aquatints and Mezzotints are also thoroughly described. For connoisseurs and professional artists already familiar with the traditional techniques of etching, woodcut, and lithography, Pressed in Time offers a dizzying array of gorgeously executed prints, but it’s also evident that some of the artists in the show were experimenting with relatively new techniques for their day.

Serigraphy, or screenprinting, can be traced to the textile industry of ancient Japan, where screens made of silk or hair printed stencils with assorted motifs and patterns onto kimono fabrics. The process was advanced in England during the early 1920’s, and used mostly for commercial printing, however, the serigraphic print would not be elevated to a high art form until the 1960s. Nonetheless, the Pressed in Time exhibit clearly shows American social realist artists using silkscreen printing to great effect. The Hitchhiker by Robert Gwathmey is one such serigraphic print.

Gwathmey’s 1937 print is modernist in the extreme, angular forms and flat colors arranged so that the negative space filled by a blank sky becomes oppressive – just like the hot summer’s day the artist meant to suggest. But the topic of the print is not stifling weather, it’s racial and class oppression. Two black men looking for work are depicted hitchhiking along a road, the fact that they are going in opposite directions tells you that their quest is a luckless one. The backdrop to their bleak pursuit is a series of roadside billboards advertising wealth and luxury; on the right a giant lobster can be seen – a promise of foods never to be tasted by unemployed workers. The two remaining billboard images are of fashionable blond women, reminders that those with dark skin are not included in America’s vision of success.

Robert Gwathmey (1903-1988) was born into a poor white family in Richmond, Virginia, but he devoted a large part of his art towards presenting the dignity and beauty of African Americans, as well as portraying their plight of being denied full human and civil rights. Like so many of his contemporaries, he focused his considerable talents on presenting the realities of the day, the Great Depression, racial and social injustice and the brutalities of poverty. Gwathmey was wholly dedicated to the honest portrayal of the working class – black and white. When he was awarded a fellowship from the Rosenwald Foundation in 1944, he used the grant money to arrange his living on a tobacco farm for a year, where he worked the fields with Black sharecroppers and created artworks that depicted their lives and struggles.

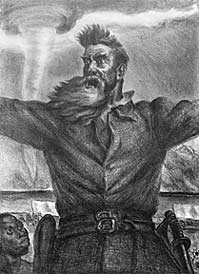

Like Grant Wood and Thomas Hart Benton, artists whose impressive prints are also included in Pressed in Time, John Steuart Curry was a leader of the American school of painters who came to be known as the Regionalists. Curry devoted his considerable talents to an examination of his native state of Kansas, believing that the very essence of America could be found by telling the stories of the heartland’s humble working people. His most well known paintings were those created as murals for the Kansas Statehouse. The most famous of those murals, the remarkable Tragic Prelude, portrays the radical abolitionist John Brown against a backdrop of a gigantic tornado and a raging prairie fire. Curry utilized the tornado as “a biblical pillar of clouds to guide John Brown in his struggle for a free Kansas.” Flanking Brown and facing each other are the anti and pro-slavery militias that waged the fratricidal clashes that would be the prelude to the Civil War.

Pressed in Time includes three significant lithographs by Curry, the thundering portrait John Brown – based upon the Tragic Prelude mural, and two other prints that have to do with Blacks held in bondage. Man Hunt shows an armed mob of whites with packs of frenzied blood hounds, searching the woods for a Black person on the run. The subject here is not the fleeing soul (who you don’t even see), but the inhumanity and bloodlust of the white racist hooligans. A chilling companion print, The Fugitive, cuts closer to the bone. It depicts the conclusion of the mob’s hunt, where a Black man has attempted to save himself by climbing up a tree to hide in the branches. The racists have not yet found their exhausted prey, but the end seems near. The terrible finale is symbolized by two Luna moths settled on the tree – that particular type of moth lives only one day after emerging from its cocoon.

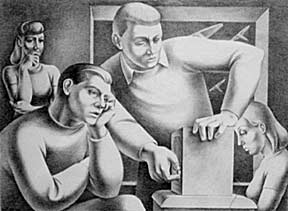

Rumors of War, a 1939 lithograph by Pele deLappe, portrays the growing concerns held by Americans as the country slid towards direct involvement in the Second World War. The artist depicted a room full of people, two men and two women (the standing woman in the background is the artist’s self-portrait), paying rapt attention to a radio broadcast. What terrible news might they have been listening to? In 1939 the Nazis invaded Czechoslovakia in March, and the Italian fascists occupied Albania in April, the same month the Spanish Republic fell to fascists under General Franco. Joseph Stalin and Adolf Hitler would sign a non-aggression pact in August, and the Nazis would invade Poland in September. There was plenty of bad news to be heard – and the gloomy looks on the faces of the characters drawn by deLappe seem to tell us that they’ve heard it all. Warplanes fly past the open window of the room they inhabit, an omen of what was to come – the USA would officially enter the war in 1941.

For those unable to take in the exhibit, an informative and beautifully illustrated catalog book is available. Pressed in Time: American Prints 1905-1950, is on exhibit until January 6th, 2008, at The Huntington Library’s, Boone Gallery. Admission is free to all visitors on the first Thursday of every month – but you must reserve a free day ticket. Otherwise, general admission is $15 for adults, or $12 for Seniors and $10 for students. More information about the exhibit can be found on The Huntington’s website.