The Art of Bernard Zakheim

Enthusiasts of American social realism are generally familiar with the outstanding murals that were painted in 1934 on the interior walls of San Francisco’s Coit Tower. Few however, can name a single artist out of the twenty-six that worked on the murals inside the splendid Art Deco tower. One of those artists was Bernard Baruch Zakheim (1896-1985), a Jewish immigrant from Poland who would make San Francisco, California his home in 1920, becoming active in the Jewish community and the city’s bohemian circles of artists and left-wing activists. A number of Zakheim’s works are now exhibited at the A Shenere Velt Gallery on the Westside of Los Angeles until October 23, 2009.

Titled Bernard Baruch Zakheim: Paris, San Francisco and Beyond, the exhibition is made up of 24 paintings and drawings created by the artist from the early 30s to the late 50s. I attended the opening of the exhibit and was pleased to meet the artist’s son, Nathan Zakheim, who regaled me with tales of his father’s life and work. It was a fortuitous encounter that gave me further insight into the creative output of Bernard Zakheim. Consisting mostly of sketches, watercolors, and studies for murals never created, the exhibition presents works that have rarely, if ever, been shown in public.

Nathan Zakheim told me that his father lived in Los Angeles for a short time in the late 1920s, and at some point produced costume and set design sketches for the Yiddish theater. A number of sketches created for a production of The Doctor by the famous Yiddish playwright Sholem Aleichem, are included in the exhibit. The gestural and humorous nature of these drawings makes them a sheer delight, but they are also important in that they are documents of the vibrant Yiddish theater scene that once existed in L.A. The adaptation of The Doctor that Zakheim worked on took place at the Wilshire Ebell Theater – then a major venue of literary Yiddish plays in L.A. along with the Assistance League Playhouse in Hollywood and The Globe Theater (now the New Beverly Cinema).

Two works on display in the exhibit, a finished sketch for a mural on medicine and immunology and a preliminary painting titled, The Donner Party, were submitted as mural proposals to the Works Progress Administration (WPA) in the mid-1930s, but unfortunately were never commissioned. Zakheim’s sketch for the immunology mural is related to the well-known 1935 mural he created on the history of California medicine for the University of California Medical Center in San Francisco. Notwithstanding being a classic example of art from the 1930s, the mural sketch on display at the A Shenere Velt Gallery is a lost treasure of sorts. I can only speculate as to why the WPA did not approve Zakheim’s immunology mural, but the drawing certainly belongs in a museum collection.

The Donner Party is an especially moving painting based upon the doomed party of some 80 American settlers who attempted to reach California by covered wagon in 1846, but instead became snowbound in the Sierra Nevada – where they resorted to cannibalism in order to survive. Painted with tempera on paper, the study has the look and brush strokes of a fresco mural, and no doubt Zakheim intended it to be a mural for a post office or school. The painting depicts two figures, a seated man in a state of torment, and the woman who comforts him with her merciful touch. The man’s left hand is clenched into a fist of anguish and he wears a look of dismay upon his face, having just realized what he must do in order to stay alive. The woman has placed her hand upon his in a gesture that conveys acceptance of the unavoidable. The profundity of Zakheim’s painting goes well beyond the depiction of a tragic event in American history, instead it speaks of the “human condition”; the needless suffering people everywhere must endure in life. The work was also prescient, as the couple Zakheim painted could have been – just a few years later – European Jews contemplating annihilation under fascism.

Bernard Baruch Zakheim’s life as an artist was set in motion when he was a young man in Poland, but one could say that his professional career actually began once he settled in San Francisco. In June of 1930 he organized the city’s First Yiddish Art Exhibition, a showing of Jewish painters, sculptors, poets, and composers from San Francisco. He had developed a fascination with the socially engaged artists of the Mexican Muralist Movement, and was particularly interested in Diego Rivera, and so he sent the Mexican muralist a portfolio of drawings for comradely appraisal – a deed that would end up transforming Zakheim forever. Rivera would invite Zakheim to his studio in Mexico City, and when the two met in 1930 Rivera praised Zakheim’s drawings of Jewish life, commenting that “every artist puts into his work something of his own soil, of his own people.” Zakheim worked with Rivera long enough to know that his future lay in creating public works of art that were challenging in nature.

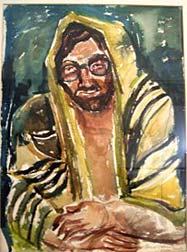

After his encounter with Rivera, Zakheim would make a sojourn to Paris, France in 1931, where he created a number of sketches and watercolors. A few of these are included in the exhibit, like the spontaneously painted watercolor portrait, American Girl in Paris, and Student Scholar, which provides a depiction of Orthodox Jewry in Paris just prior to the Nazi occupation of 1940. Zakheim returned to San Francisco in ’32, receiving his first mural commission a year later from the newly-built Jewish Community Center at the intersection of California Street and Presidio Avenue. While Zakheim was a secular Jew absorbed in socialist politics, he always thought it important to highlight Jewish culture and heritage in his art, and so his mural for the center was a celebration of Jewish life. The mural depicted a festive Jewish wedding celebration, with rabbis, wedding couple, musicians, dancers, and athletes. The press wrote good reviews about the mural, no doubt pleased that the bohemian left-winger had avoided doing something controversial – but that would soon change.

In 1933 Zakheim and fellow artist Ralph Stackpole lobbied the government for a commission that would allow artists to paint murals on the interior walls of San Francisco’s newly constructed Coit Tower. Their efforts paid off when in 1934 the Public Works of Art Project (PWAP) gave twenty-six artists – Zakheim and Stackpole included – the task of creating the Coit murals under the direction of Victor Arnautoff.

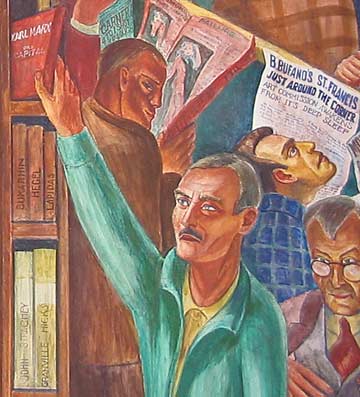

Zakheim chose to depict a U.S. public library in his mural – it would become his most well-known and contentious work. He painted a number of his friends into the mural, like the anarchist poet Kenneth Rexroth, depicted on a ladder reaching for a book on a top shelf. In the upper-right corner of the mural Zakheim painted the modernist sculptor Beniamino Bufano reading a paper with the headline, B. Bufano’s St. Francis Just Around The Corner. It was a reference to Bufano’s 18-foot granite statue of St. Francis of Assissi; a sculpture finally set in place in front of the Church of St. Francis in San Francisco on August 27, 1955. Bufano was certainly a colorful character; thoroughly bohemian, but a devout Roman Catholic in addition to being an anarcho-pacifist. When President Woodrow Wilson declared war on Germany in 1917, Bufano chopped off the trigger finger of his right hand and mailed it to the president as a protest against America’s entry into the war.

Zakheim also worked fellow Coit Tower muralist and friend John Langley Howard into The Library – reaching for a copy of Karl Marx’s Das Kapital. Zakheim was twice asked by officials to obliterate the reference to Marx from his mural, and his refusal to do so almost scuttled the entire project. Ultimately Zakheim’s stubbornness prevailed and Das Kapital remained.

Starting in 1940 Zakheim began a series of remarkable easel paintings titled Jewish Patriots of the American Revolution. The works revealed and commemorated the historic role of Jews in the anti-colonial American Revolution waged against the British Empire. When American patriots began the Revolutionary War of Independence against Great Britain, there were fewer than 2,000 Jews living in the 13 colonies, and the majority of them championed and fought for the anti-colonial cause. Zakheim wanted people to remember that history, and so began his group of paintings. One of the canvases was titled, Revolutionary Patriot Chaim Soloman revealing secrets of Red Coat military activities to an American Officer.

Chaim Soloman was an early member of the Sons of Liberty, a secret mass organization of anti-colonial rebels in the Thirteen Colonies whose slogan was “no taxation without representation.” The Sons of Liberty attacked the property and symbols of British power, with the group’s most famous propaganda of the deed being the 1773 Boston Tea Party. More importantly, as a wealthy broker Soloman became a primary financial backer of the American Revolution. Zakheim painted a tableau in which Soloman appears as a revolutionary spy, passing on intelligence information about the Red Coats to an unidentified commander of the American Continental Army. In actuality the British arrested Soloman for spying in 1776. Though pardoned, he was arrested again in 1778 and sentenced to death. He escaped to the rebel capital of Philadelphia were he resumed his duel role as financial broker and pro-Independence revolutionary.

Unfortunately the Zakheim exhibition at the A Shenere Velt Gallery is rather limited in scope, presenting only a small number of sketches and paintings from the artist’s enormous body of work. Perhaps a comprehensive retrospective of his art will someday be mounted by a museum; such a showing is certainly long overdue. In the meantime I have attempted to pique the interest of those unfamiliar with Zakheim by mentioning some of his paintings not included in the exhibit just reviewed. I also suggest visiting www.bernardzakheim.com, which handles the artist’s estate.

UPDATE: 3/14/2016

Bernard Baruch Zakheim: Paris, San Francisco and Beyond ran at the now closed A Shenere Velt Gallery, once located on the Westside of Los Angeles.