Guayasamín: Rage & Redemption

Of Rage and Redemption: The Art of Oswaldo Guayasamín was an important two-year long traveling retrospective of artworks by Latin American master, Oswaldo Guayasamín (1919-1999). The exhibit recently ended its scheduled tour last August 16, 2009 at the Museum of Latin American Art (MoLAA) in Long Beach, California. Guayasamín, hailed in his home country of Ecuador as a national hero and widely acclaimed throughout Latin America and indeed the world – is scarcely known in the United States. What accounts for this near total lack of recognition? Emphasizing the magnitude of his omission from public awareness in the U.S., I overheard someone say while viewing the show, “I’ve never heard of Guayasamín before. I don’t mean to sound sacrilegious, but I think he’s better than Picasso.”

Expertly curated by Joseph Mella, Director of the Vanderbilt University Fine Arts Gallery in Nashville, Tennessee, Of Rage and Redemption first premiered in February of 2008 at the Vanderbilt before moving on to four other national venues, including a run at the Organization of American States’ Art Museum of the Americas in Washington, D.C. The exhibit was laid out as a timeline, starting with the artist’s early figurative works from the 1940s, and culminating with his late period minimalist paintings from the 1980s and 1990s. Walking through the exhibit not only gave insight into Guayasamín’s artistic development over the decades, it presented an overview of history as it occurred in Latin America and throughout the world, since the artist was deeply concerned with real world events. In his own words:

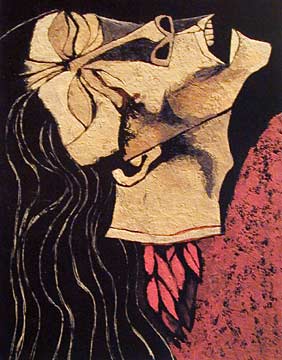

“I have used a powerful weapon, the plastic, to denounce and protest the bad behavior of ‘man against man.’ I speak the truth of my time, without the picturesque or the anecdotal. I don’t look for beauty – but for truth. I use the body of humanity to show the present and historical reality, without academic euphemisms; this humanity – tortured by injustice, misery and horror, is present in The Wretched of the Earth by Franz Fanon.”

While Guayasamín was undoubtedly influenced by modernist aesthetics, he wanted to move away from European traditions in art. One might see the German Expressionists in his agitated brushstrokes and figurative exaggeration, but Guayasamín’s unique late style was inspired by the ancient civilizations of pre-Hispanic America; it was Inca, Maya, and Aztec aesthetics that fired his imagination and guided his vision.

The Maya murals of Bonampak, Mexico painted in 790 AD and the Inkapirqa (Inca wall), built in Ecuador by the Inca in the late 15th century before the Spanish conquest – had more to do with Guayasamín’s artistic vision than anything offered by the European avant-garde of the late 20th century. In part it was this “indigenismo”, the utilization and further development of deep-rooted indigenous aesthetics that made Guayasamín’s art so greatly admired throughout Latin America.

I would like to remark on a number of paintings presented in the exhibit, for example, the oil painting titled Napalm. It condemned the incendiary weapon made infamous by its massive use in Vietnam by the U.S. military. Guayasamín’s terrifying canvas looks as if it were made from scorched flesh and coagulated blood. Painted in 1976, the canvas surely alluded to Kim Phúc, the little Vietnamese girl who was severely burned in a napalm attack that took place in 1972.

Photos and motion picture film of Phúc running down a village road, her clothes burned off and her seared flesh hanging in strips, became some of the most unforgettable imagery from the Vietnam War. But Guayasamín was also undoubtedly thinking of how napalm had been used in Latin America as well. In 1965 the Peruvian army bombed guerrilla fighters at Mesa Pelada with U.S. supplied napalm, and in 1968 the Mexican government used the U.S. furnished jellied gasoline against guerrilla groups operating in the southern coastal state of Guerrero.

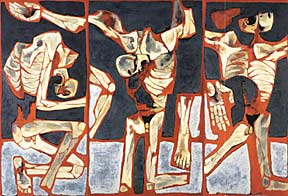

The canvas Los Torturados (The Tortured) alludes to another tragic moment in history. Painted in the years 1976-77, Guayasamín’s canvas at first glance seems a commentary on the torture of civilians at the hands of military regimes, which indeed it is – but the artist had something more specific in mind. Chile’s democratically elected government of Salvador Allende was overthrown on September 11, 1973, in a brutal military coup backed by the United States. Some 3,000 civilians were killed and thousands more were detained by the military junta.

One of those arrested was Victor Jara, the famous Chilean folk singer and supporter of the deposed socialist government. He was taken by the army to Chile Stadium in Santiago, then being used as a torture and detention camp for thousands of prisoners. Once they realized the celebrated singer was in their custody, soldiers began to savagely torture Jara. Troops broke both of his wrists and crushed the bones in both of his hands with rifle butts before machine-gunning him.

Three years later Guayasamín would dedicate Los Torturados to the spirit of Victor Jara. In 2004 a new democratically elected government honored the memory of the slain singer by renaming Chile Stadium, The Victor Jara Stadium. In 2008 a Chilean government investigation and autopsy confirmed that Jara had been tortured and shot 44 times. Finally, in May 2009, a former low ranking army conscript was charged with the murder of Jara.

Another impressive oil painting in the exhibit was the monolithic, Reunión en el Pentágono I-V (Meeting at the Pentagon I-V). The five panels created in 1970 offer psychological portraits of fictitious U.S. military chiefs conspiring behind closed doors.

While viewing the panel portraits it is difficult not to think of director Stanley Kubrick’s doomsday film, Dr. Strangelove or: How I Learned to Stop Worrying and Love the Bomb, not for any intentional connection Guayasamín made to Kubrick’s cinematic masterwork, but simply because the paintings so brilliantly depict men whose minds have become unhinged by militarism.

While Kubrick drove home his point with dark humor, there is little of a comedic nature to be found in Guayasamín’s rough semi-abstract caricatures of the militarists. His military chiefs are Machiavellian ideologues practiced at placing lives in the balance for the sake of political expediency and bellicose Cold War objectives.

One is almost tempted to chuckle at the men in the portraits for all of their pomposity and ridiculous jingoism, but quiet laughter seems inappropriate. Guayasamín and his compatriots had seen too many hearts and souls crushed by real jackbooted tin horn dictators to find anything funny about them or their shadowy benefactors.

The technique employed by Guayasamín in creating the panels added to the work’s powerful narrative. He literally troweled oil paint onto the panels, spreading and smoothing it in places, scoring and scraping it off in other areas. Repeated applications of paint applied in this manner resulted in a textured surface over which he applied glazes of color. His figures were painted on a black underpainting, and his finishing brush strokes of black were painted into wet color. The painting is a tour de force, full of lustrous transparencies, aggressive brush strokes, and remarkable textures.

Guayasamín’s masterful handling of paint bestowed upon his subjects a surprising if distorted humanity. One appears as a fleshy bureaucrat and another as a rhinoceros-skinned brute. One blue-eyed fellow hunched over at his desk with a look of consternation etched upon his face displays an unexpected vulnerability. The shred of morality he still possessed had been stirred; his eyes convey self-loathing – or is it extreme doubt – over something he has done or is about to set into motion.

The history of U.S. military intervention in Latin America is so extensive that one could devote an entire lifetime to its study. U.S. military invasions and occupations in the hemisphere pre-dated the existence and influence of the Soviet Union, often cited as the reason for the U.S. engineered coups and assassinations that took place in the 20th century.

Prior to the founding of the Soviet Union there were at least 25 major U.S. military interventions in Latin America, from the 1848 war of the United States against Mexico – one of the most shameless land grabs in world history – to several thousand U.S. Marines occupying the Dominican Republic in 1916.

Guayasamín’s Meeting at the Pentagon portraits adhere to the profile of military leaders from “El Norte” that Latin Americans have long held, and there has been little recent evidence given to make them change their minds. Despite President Obama’s assurances that there will be “no senior partner and junior partner” in U.S.-Latin American diplomatic relations, his actions speak otherwise. His near passivity regarding the June 28, 2009 coup d’état in Honduras have left many wondering if Obama tacitly approves of the military coup.

Every Latin American nation has withdrawn its ambassador from Honduras in protest of the coup, and member states of the European Union have done the same – it is only the U.S. that has failed to do so.

UPDATE 9/22/2016: Since the 2009 coup in Honduras, overwhelming evidence has emerged that shows former Secretary of State Hillary Clinton played a major role in supporting the military overthrow of the democratically elected government.

Worse yet, Obama has struck a deal with the right-wing government of Colombia, giving U.S. military forces long-term access to seven military bases across that country and allowing for an expanded U.S. military presence in Colombia. At an Aug. 28, 2009 emergency meeting of the South American Union of Nations (Unasur) held in Argentina, South American heads of state blasted the Obama plan as a threat to regional peace and stability.

It was Simón Bolívar who once intoned, “Nuestra Patria se llama América” (The name of our country is América); an axiom that gave expression to a vision of hemispheric unity so deeply instilled in Latin Americans that many still take umbrage when citizens of the United States use the name “America” to mean U.S. national exclusivity and pre-eminence.

Born in Caracas, Venezuela, Bolívar (1783-1830) came to be known as “The Liberator” for his leading role in the independence movement against the Spanish. Revered throughout Latin America for having smashed Spanish colonial rule in Bolivia, Ecuador, Colombia, Panama, Peru, and Venezuela, it was Bolívar’s pan-American vision that inspired and inflamed Latin American patriots ever since his death.

That same pan-national fervor permeates Guayasamín’s art, yet it would be a mistake to view him as an artist who was devoted only to the people of the Americas; the core of his art was a passionate universal humanism.

Strolling through the exhibit was akin to reading the works of Uruguayan author Eduardo Galeano, in that Guayasamín presented the region’s anguished history in a visual language similar to the hallucinatory verse of Galeano. I first read Galeano’s The Open Veins of Latin America, an authoritative history of the Americas from 1492 to the late 20th century, in the late 1970s; I have followed his writings ever since. However, it was his magnificent 1985 trilogy, Memoria del Fuego (Memory of Fire) that remains a favorite work of mine. A non-prosaic chronicle of the continent’s history, Memory reads like an epic poem that begins with the creation myths of indigenous people before there was written history, and ends in 1984 with a peasant fiesta in Bluefields, Nicaragua, where; “however much death may come, however much blood may flow, the music will dance men and women as long as the air breathes them and the land plows and loves them.” Galeano’s trilogy is a remarkably powerful and insightful work, and Guayasamín’s art is the closest visual equivalent I can think of.

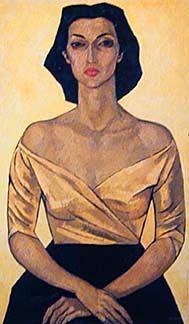

Despite its profundity, the Of Rage & Redemption exhibition had its flaws, the greatest of which was overlooking Guayasamín’s extraordinary power as a modernist portraitist. Save for a few realistic early works, the exhibition focused mostly on the artist’s mid to late period minimalist style, where he reduced the human figure to near abstraction. On the whole, the viewer was left with a rather narrow view of Guayasamín.

To fully appreciate the weight of Guayasamín’s art one must begin with his portraits, of which he created hundreds over the expanse of his career. Without sentimentalism or showiness, Guayasamín painted the likenesses of friends, relatives, associates, workers, and fellow artists.

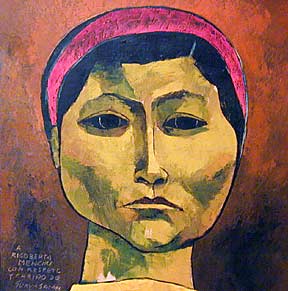

As time went on he would also paint celebrities and presidents, but of those who sat to have their portrait painted – whether campesino or luminary – all were painted as equals. There were no “natural rulers” in Guayasamín’s universe; the only sovereigns were those who struggled against cruelty and injustice. The list of those who had their portraits painted reads like a directory of Latin American notables; Atahualpa Yupanqui, Mercedes Sosa, Pablo Neruda, Gabriel García Márquez, Fidel Castro, Rigoberta Menchú Tum, Francois and Danielle Mitterrand, and many others.

Guayasamín’s style of portraiture was largely based upon exaggerated caricature, yet his portraits were never cartoonish. Portraits from the 1940s and 1950s were generally more realistic, but his later period primitivist approach in no way bordered on kitsch, and while he stripped away superfluous details he always succeeded in capturing the unique spirit of his individual sitters. In its totality the body of Guayasamín’s portraiture can be viewed as the collective face of Latin America’s people.

It is a shame that more people in the United States are not familiar with the works of Oswaldo Guayasamín, but his not being well-known in the U.S. is an issue of some complexity. The fashionable art world of today, transfixed as it is with the strictures of postmodernism, essentially does not know what to make of such an artist. Irony, cynicism, and lack of introspection, are the hallmarks of today’s trendy art – all notions antithetical to Guayasamín’s work.

One can imagine the nauseating kitsch of Jeff Koons’ Michael Jackson and Bubbles on display at the Broad Contemporary Art Museum (BCAM) at the Los Angeles County Museum of Art – but it is impossible to imagine Guayasamín’s memorial to the spirit of Victor Jara hanging in the same institution. Despite my differences with the Museum of Latin American Art, it deserves credit for mounting the Guayasamín retrospective.

For more information on the work of Oswaldo Guayasamín, visit the official website of the Guayasamín Foundation. MoLAA offers a small illustrated catalog of the exhibit, which is available at the museum’s gift shop. However, a splendid and much superior collaborative book by Guayasamín and Chilean poet Pablo Neruda can be purchased through Amazon. Titled America, My Brother, My Blood, the book combines words and poetry by Neruda with paintings and drawings by Guayasamín.

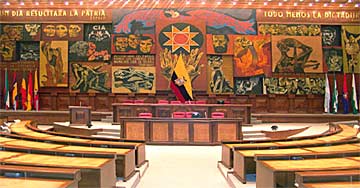

Image of the Mother Country, a colossal mural commissioned by the government of Ecuador, hangs in that country’s Legislative Palace (Congress) in the capital of Quito. The National Assembly of the Republic of Ecuador maintains an illustrated Spanish language .pdf file that explains the history and narrative of the mural – which was installed and officially unveiled in 1988.