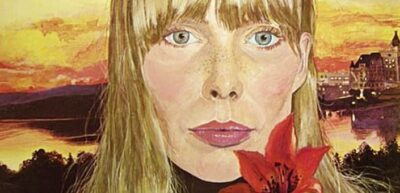

Karl Bodmer: Faces from the Interior

As an artist, I see Karl Bodmer’s artworks as key to understanding America. I discovered his works in the late 1960s and have studied them every since. He was an artist-adventurer in the mid-1800s who travelled the wilds of North America to document the lives of indigenous people with sketches, water colors, and elaborate oil paintings.

I always found Bodmer’s portrayals of Native Americans to be dynamic and sympathetic. His depictions were not only gorgeous, but incredibly accurate. They were in fact so detail-oriented that historians and anthropologists have turned to them for a faithful look at the past. Remarkably, he is still not widely recognized in the US, but Karl Bodmer: Faces from the Interior, a nationwide traveling exhibit, might help change that. As I write this the exhibit is at the Amon Carter Museum of American Art in Texas, where it closes on Jan. 22, 2023.

Bodmer was not the only artist to travel into uncharted territory to paint tribal people. John Mix Stanley, Alfred Jacob Miller, and George Catlin did the same. Catlin’s impressionistic paintings captured the essence of his indigenous sitters, and he remains one of my favorite American artists of his day.

The Bodmer exhibit displays beautiful, highly detailed watercolors and sketches the artist made of Native Americans while traveling up the Missouri River between 1832 and 1834. The works portraying free and autonomous indigenous tribes have great historic and artistic significance. The artist was only 23-years-old at the time, and he gifted the world with a clear and unsentimental view of a bygone era.

The tale began with Prince Maximilian zu Wied-Neuwied (1782-1867), who was the ruler of the small state of Neuwied, Prussia (now Germany). Maximilian was an explorer, ethnologist, zoologist, and naturalist, and in 1815 he organized an expedition to southeast Brazil that made tremendous contributions to the understanding of the indigenous people of that region.

When 50-years old, Maximilian organized a similar expedition to the US in 1832. His objective was to study and document Native American tribes living in the wilderness, as well as study the flora and fauna of the country. The excursion launched from the city of St. Louis at the confluence of the Mississippi and Missouri Rivers. Everything west of the Mississippi was “Indian Country” where few whites, aside from fur trappers, had sojourned. Maximilian intended to meet tribal people by traveling to the Rocky Mountains with frontiersmen and trappers of the Rocky Mountain Fur Company during one of their fur-trading caravans.

In St. Louis prior to his mission, Maximilian was counseled by the following men. William Clark of the Lewis and Clark Expedition, Major Benjamin O’Fallon, who was President Monroe’s Indian Agent for the Upper Missouri, Joshua Pilcher, a leader of the Missouri Fur Company that travelled deep into the Rocky Mountains, and John F. A. Sanford, government agent for tribes along the Missouri. They all cautioned against traveling with frontiersmen, arguing that mountain men avoided contact with Indians and encounters were usually hostile. The Blackfoot in the region were particularly warlike, they controlled trade in beaver pelts by forcing all other tribes out of the Rockies and killing whites who encroached on their lands. Plus, moving large scientific collections through perilous territory would be a daunting, if not impossible enterprise.

Maximilian abandoned his plans to visit the Rockies. Instead Clark, O’Fallon, and the other advisors convinced Maximilian to travel up the Missouri River on the “Yellowstone,” a steamboat built by the American Fur Company to help facilitate the fur trade. The plan was to travel up the Missouri to the Fort McKenzie trading post, and then return to St. Louis. Along the way the steamboat would unload supplies at the company’s various trading posts were Plains Indians engaged in the friendly trade of furs for European goods. O’Fallon provided Maximilian with a copy of the 1803-1806 Lewis and Clark Expedition map, a topographical depiction that proved indispensable.

The scientifically minded Maximilian desired meticulous documentation of Native Americans and their environs, so he hired the 23-year-old artist Karl Bodmer (1809-1893). Bodmer was born in Switzerland and was proficient in the European traditions of classical art. Known as a printmaker skilled in etching, engraving, and lithography, he was also appreciated as a watercolorist and oil painter who created splendid landscapes. Also on the trek was a skilled hunter, taxidermist, and servant to Maximilian named David Dreidoppel; he had accompanied the Prince during his Brazil trip. In essence the expedition was three men; Maximilian the scientist, Bodmer the ingenious young artist, and Dreidoppel the efficient huntsman and master of taxidermy.

On April 10, 1833, the Maximilian-Bodmer expedition began its hazardous trip up the Missouri River on the Yellowstone steamboat. It was the first “side wheeler” steamboat to operate on the Missouri; powered by two steam engines, its steel mechanical paddle wheels measured 18 feet in circumference. One was fixed to each side of the ship. The 144 ton ship was 120-feet in length, with three boilers, twin smoke stacks, and a crew of 24 men. Some 100 people were on board and they were mostly employers of the American Fur Company.

In a 1833 watercolor, Bodmer depicted the Yellowstone steamboat trapped on a Missouri River sandbar early in the expedition, its crew struggling to free the ship. Knowing his discerning eye, it was likely a very accurate depiction of the boat. Previously, on March 26, 1832, artist George Catlin travelled up the Missouri on the very same Yellowstone steamboat to the mouth of the Yellowstone River. This is when he began painting his canvases depicting the indigenous people of the Great Plains. Before his epic journey Catlin painted “St. Louis from the River Below” depicting the Yellowstone steamboat sailing up the Mississippi. It was one of the very first paintings of a city on the Mississippi.

On April 22 the Yellowstone steamboat first stopped at Fort Leavenworth in Kansas, ten days later it reached Bellevue Trade Post in Nebraska; also known as Fontenelle’s Post. By the end of May the steamship arrived at Fort Pierre in South Dakota—the American Fur Company’s main trading post among the Sioux. At this point the Maximilian-Bodmer expedition transferred to the Yellowstone’s sister ship the “Assiniboine,” which continued upriver while the Yellowstone returned to St. Louis. The Assiniboine steamed out of Sioux territory and into the land of the Mandan; on June 18 it landed at Fort Clark (also known as Fort Osage) for a day before steaming on to Fort Union, where it moored on June 24. Since their departure from St. Louis, the Maximilian-Bodmer expedition had been traveling upriver into Indian territory for seventy-five days.

Fort Union was a principal post for the American Fur Company. Like all the other forts it was not a military installation, but a privately owned, heavily fortified trading post run by the company.

The Yellowstone and Assiniboine steamboats stocked those posts with items like steel knives, hoes and axes, blankets, handkerchiefs, mirrors, combs, toothbrushes, soap, buttons, glass beads, bells, tin kettles, buckets and cups, yards of fabric and ribbon, thread, cotton shirts, awls, mens boots and women’s shoes, socks, tin spoons, pins, needles, razors, scissors, vermillion and indigo pigment dye, gunpowder, gun flints, and lead (to cast bullets), and much more, even tobacco.

White trappers came in to barter for supplies, but natives flocked to the forts to trade furs; buffalo robes and beaver, mink, marten, otter, fox, winter weasel pelts, and other furs were traded for European trade goods. Those items had a huge impact on native culture.

Being equipped with thread, needles, glass beads, and trade cloth was transformative enough, but trade posts also offered the North West Gun and other firearms to Plains tribes. The North West was a .62 caliber (20 gage), smoothbore black-powder flintlock that was light, sturdy, and easy to maintain. It could be loaded with a single large lead ball or with dozens of lead pellets. The North West Gun expanded a tribe’s wealth by increasing the amount of game that could be harvested, but it also changed the dynamics of inter-tribal warfare and the way Plains warriors battled whites.

After six days at Fort Union the expedition made a five-week, 650 mile voyage to Fort McKenzie in Montana on a “keelboat” named Flora.

While keelboat sailing ships had been replaced by larger and faster steamships on rivers, the keels continued to sail on tributary rivers or shallow waters where steamships dare not go, like the upper Missouri.

A keelboat was long and narrow, averaging around sixty feet long and eight feet wide; outfitted with sails, masts, and rigging, it could have a crew as large as 25 men and carry over 20 tons of supplies. The advantage of the keelboat was its ability to navigate shallow or otherwise tricky waters; a crew on shore could tie a rope to the boat’s mast, then pull the ship upstream. If river conditions grew dire in high water the crew could “bushwhack” the boat upriver by literally grabbing shoreline bushes and trees, and pulling the ship forward.

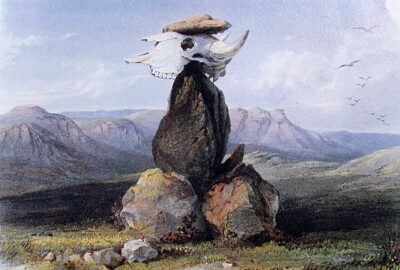

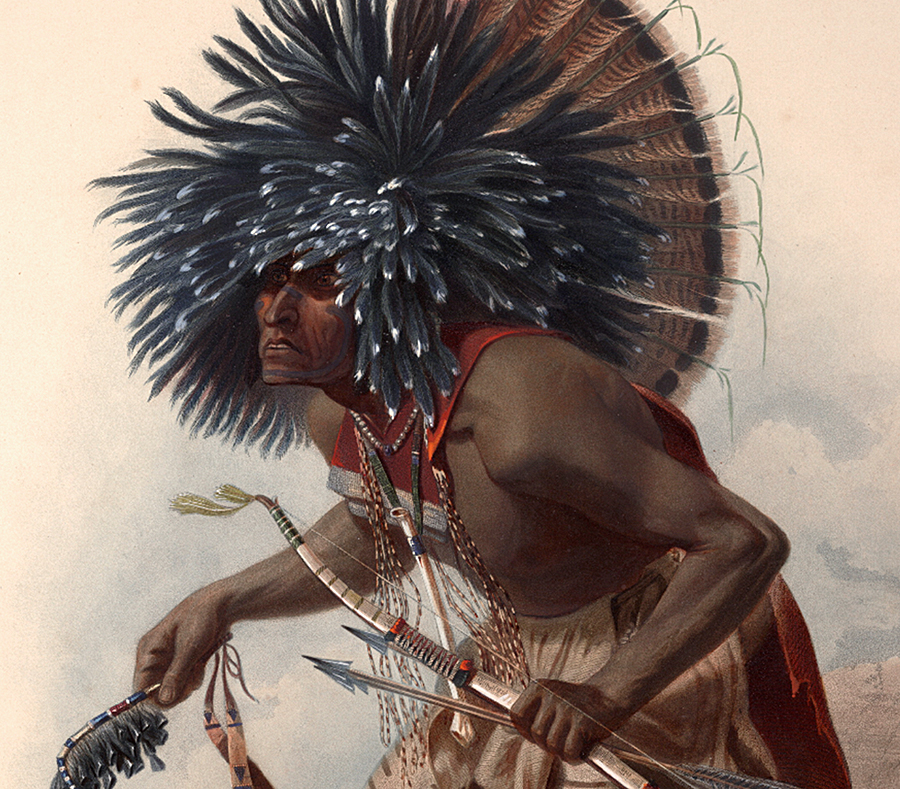

The Maximilian-Bodmer expedition reached Fort McKenzie on Aug 9, and they would stay until Sept 14, 1833. Bodmer kept busy painting watercolor portraits of Blackfoot, Blood, Piegan, and Assiniboine warriors and chiefs who came to trade; he also painted the wilderness surrounding the fort, as well as the compound itself.

On August 28 Bodmer and party witnessed a ferocious battle outside the fort when hundreds of Assiniboin and Cree viciously assailed a Blackfoot encampment. All weapons came into play during the ruthless sortie; bows and arrows, lances, scalping knives, war clubs, and guns. Blackfoot warriors rallied and drove back the attackers, but not before dozens were wounded or killed.

Bodmer watched the bloody melee from the safety of the fort’s parapets. He would base one of his most memorable prints on the conflict. Titled Fort McKenzie, August 28, 1833, the artist created the watercolor in a European studio once he returned home from the expedition. He composed the scene from memory, basing the painting on field sketches and character studies he made at Fort McKenzie. Rather than depicting the bloody fracas as he observed it from behind the trading post’s stockade walls, Bodmer brilliantly placed the viewer right in the middle of the bloodshed. After the skirmish, tensions remained high at Fort McKenzie. Believing there would be more fighting, the Maximilian-Bodmer expedition decided it was time to leave the trading post.

On Sept. 14, 1833 the expedition sailed another keelboat back down the Missouri past Fort Union, to spend the winter at Fort Clark (aka Fort Osage). That is where the expedition spent time with three associated tribal groups unlike any other living on the great plains, the semi-nomadic Mandan, Arikara, and Hidatsa. Bodmer created sketches and watercolors of their daily lives and rituals, homes, and environs, not to mention some very fine portraits.

The Mandan, Arikara, and Hidatsa stood apart from other plains tribes because they practiced agriculture. They farmed large fields of corn, beans (black, red, spotted, white), along with pumpkins and different squash varietals, sunflowers and tobacco. Plains tribes like the Sioux would trade fur and buffalo meat for fresh and dried vegetables from Mandan, Arikara, and Hidatsa farmers.

As revealed to European anthropologists in 1917 by a Hidatsa woman named Buffalo Bird Woman, the Hidatsa harvested and consumed a black-gray fungus that sometimes grew on ears of corn, they called it Mapë’di.

It was removed from the ear of corn and cooked with corns, beans, and squash, or dried for winter use. I assume the Mandan and Arikara—closely linked to the Hidatsa, also enjoyed the fungus in meals.

That same fungus was harvested and eaten by the ancient Aztecs, who called it Huitlacoche (whee-tla-KO-cheh). Still eaten in Mexico today and considered a delicacy. I have tried tamales and quesadillas containing Huitlacoche. Despite its unsightly appearance, it has a rich earthy mushroom-like flavor.

The Mandan, Arikara, and Hidatsa lived in fixed villages of sturdy earth lodges. The semi-subterranean homes were circular, built with heavy cotton wood posts set into the earth, and covered with a woven shell of willow branches and dried grass; thick sod and clay covered the shell. Measuring up to 60 feet across, a lodge could house up to 20 family members. Villages were usually built on cliffs above rivers and surrounded by a high wall of felled trees to protect against hostile tribes.

Lodges were arranged in circular fashion around an open village center, where dances and sacred rituals were held. During the winter the tribes lived in their earth lodges, well stocked with dried meat and vegetables. In the spring until the end of summer, they left the villages to live in teepees while hunting buffalo and other game. Thanks to Hollywood films and an inadequate education in US history, most Americans have no idea some plains Indians were surprisingly sophisticated farmers that lived in villages of rugged earthen homes.

During its travels the Maximilian-Bodmer expedition encountered the Sauk, Fox, Shawnee, Otoe, Omaha, Pawnee, Ponca, Dacota, Lakota, Yanktonai, Arikara, Mandan, Hidatsa (Minatarre), Kutenai, Plains Cree, Assiniboine, Piegan, Crow, Gros Ventre, Shoshone, Blood and Blackfoot tribes. Many had not seen whites before, only a few had exposure to trappers and fur traders. The indigenous were still living freely on the plains, and Bodmer would be the last to depict them as a wild free people.

The expedition bartered trade goods to acquire hundreds of native artifacts. Items collected included leather shirts, moccasins, headdresses, leggings, dresses, buffalo robes, snow shoes, decorated feathers, drums, flutes, eagle bone whistles, war-clubs, knives, bows, arrows, quivers, war shields of buffalo hide, catlinite pipes, medicine items and personal decorations, ceramics, furs, bags, pouches and so much more. Most items were highly decorated with paint, carvings, feathers, hair, beadwork, and extravagant porcupine quill embroidery. Bodmer made accurate catalog drawings of the items entering the collection. A few of these collected items are on display in the traveling exhibition.

When the Maximilian-Bodmer expedition returned to Germany, Prince Maximilian published a two-volume book on the North American trek. The first edition would be published in 1839 under the title Travels in the Interior of North America, during the years 1832-1834. French and English volumes followed. The book included Maximilian’s narrative of the trip, with his remarks on Native Americans and their culture, as well as descriptions of the untouched natural world they inhabited. Of the over 400 paintings and drawings Bodmer brought back, the Prince picked 81 for inclusion in the book; 48 would appear as full page engraved illustrations, the remaining 33 would be vignettes. Two versions of the book were offered, one with illustrations in color, the other with artworks in black and white.

Maximilian gave Bodmer the task of supervising production of the engravings. The artist decided on combining engraving with aquatint, a technique that produces images that look remarkably like watercolors. Bodmer worked with teams of artists in Paris, Zurich, and London to produce a suite of 81 aquatint engraving prints that were translations of his detailed original watercolors. However, Bodmer and his assistants took the aquatints further. They produced the color prints by using the “à la poupée” technique. Multiple ink colors were applied to a single printing plate using a small rag ball or “poupee” (doll) for each color. After a print was pulled, Bodmer instructed artists in adding extra hand-coloring with applications of watercolor pigments. The completed prints were a towering artistic achievement. Presently in the United States there are only twenty original editions of Travels in the Interior of North America.

Travels in the Interior of North America became an authoritative record of Great Plains life. Bodmer’s paintings of native people and his exquisite landscapes showing animals, untouched rivers, plains, and forests, provided a look at a vanishing world. The costly book was sold by subscription, but it was not a big seller. Bodmer had spent ten years of his life on the North American expedition project, but by 1847 he transferred rights to those sketches, watercolors, and aquatint engravings to Maximilian’s estate. Eventually the estate would store Bodmer’s artworks at the family’s Neuwied Castle in Germany’s northern Rhineland-Palatinate, and left forgotten for more than 100 years.

After painting American Indians on the frontier, Bodmer moved to France where he became a member of the Barbizon School of landscape painters that included the likes of Corot, Gustave Courbet, and Jean-François Millet. Bodmer exhibited his landscape paintings at three different shows at the Paris Salon from 1851 to 1863. He continued painting until his death, which came on Oct. 30, 1893 at the age of eighty-four.

As fate would have it, Karl Bodmer’s artworks were rediscovered in storage at the Neuwied Castle after World War II. In 1959 the Maximilian estate sold the Bodmer collection to the M. Knoedler & Company art dealership in New York, along with Maximilian’s journals, notes, and travel diaries. The Northern Natural Gas Company of Omaha purchased the collection and wisely donated it to the Joslyn Art Museum in 1986. Bodmer’s works remain the core of that museum’s collection.

To accompany their traveling exhibit, the Joslyn Art Museum published a book titled “Faces from the Interior: The North American Portraits of Karl Bodmer.” It is the first book to focus on Bodmer’s talent as a portraitist, and it presents over 50 watercolor portraits of people from the various tribes he visited, plus paintings of tribal ceremonies and landscapes.

The Joslyn Art Museum entered an agreement with the UK’s Alecto Historical Editions to reprint Bodmer’s engravings using the artist’s original steel and copper plates. “Restrike” prints—later impressions made from plates already used to produced a print edition, are somewhat controversial.

A restrike is not an original print authorized by the artist, who in most cases is deceased. Original first edition prints have crisp, precise detail, while a restrike is of lower quality displaying softer lines from a worn etching plate. However, the skilled artisans of Alecto Historical Editions used the same exacting methods as the original artists. While lines may not be as sharp and the colors not exact, what Bodmer fan would not want one of these prints?

The Joslyn Art Museum in Omaha, Nebraska has the largest collection of Bodmer’s North American works to be found anywhere in the world; they organized the exhibit in association with the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York City. The first leg of the traveling show took place at the Met (April 5, 2021-July 25, 2021). The exhibit then opened at the Joslyn Art Museum (Oct 2, 2021-May 1, 2022). The last leg of the exhibit is the Amon Carter Museum of American Art in Fort Worth, Texas (Oct. 29, 2022-Jan. 22, 2023).