Maurice Merlin & the Black Legion

Starting January 19, 2013 and running until April 15, 2013, Maurice Merlin and the American Scene, 1930–1947 will be on display at The Huntington Library in San Marino, California. Tracking the life and times of artist Maurice Merlin, the Huntington exhibit is the very first museum presentation of the artist’s works, even though he passed away sixty-six years ago.

The Huntington Library presented Pressed in Time: American Prints 1905-1950, a first-rate showing (Oct. 6, 2007 to Jan. 7, 2008), that gave ample evidence of the influence and moral authority the school of American Social Realism once enjoyed in the United States. Maurice Merlin and the American Scene, 1930–1947 is a comparable exhibit, though on a smaller scale.

That Merlin’s work remains unknown gives evidence to the ahistorical nature of the contemporary art scene; The Huntington show is the perfect antidote. The exhibit includes some 30 works by the artist covering a wide range of mediums – oils, watercolors, screen prints, drawings, woodcuts, and lithographs. The show also includes nine works by other artists who were part of Merlin’s circle in Detroit. He was not just another “American scene” painter; The Huntington aptly described Merlin as a “Depression-era artist with a political edge.”

Maurice Merlin moved to Detroit Michigan in 1936 when the U.S. was in the throes of the Great Depression, and he found the Motor City beleaguered by social chaos and poverty, but Detroit also had much to offer an artist with a critical vision. Visiting the city four years ahead of Merlin, the Mexican muralist Diego Rivera painted his Detroit Industry murals at the Detroit Institute of Arts between the years 1932 and 1933. There is little doubt Merlin kept a sharp eye on Detroit’s intricate political landscape and social dynamics, or that he was inspired by Rivera’s murals.

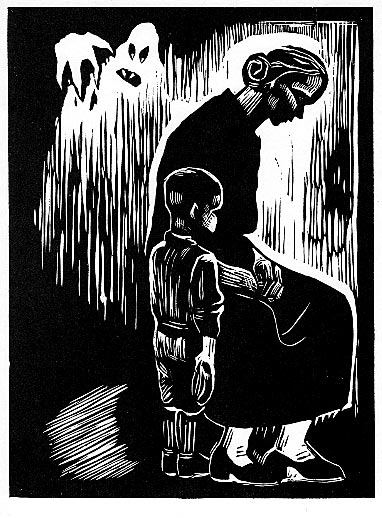

In Merlin’s Detroit, workers were unemployed in the hundreds of thousands, the city’s African American population suffered the twin scourges of privation and racist oppression, and auto workers were launching massive strikes for better working conditions and the right to organize unions. Impoverished and unable to find work, Merlin found employment with the Works Progress Administration (WPA). Like many artists of his generation, he began to document the social realities engulfing the nation and the world; his Black Legion Widow linoleum cut print displayed at The Huntington exhibit was one such work.

Though not especially indicative of Merlin’s oeuvre, Black Legion Widow is the one print from the exhibit that I wish to focus on in this review. While the narrative realism of the artist’s oil paintings and lithographs may provide a greater appreciation of Merlin’s artistic skills and accomplishments, Black Legion Widow is a consummate example of American social realism in that it captured real world events the artist was closely involved with.

While The Huntington is to be applauded for showing Maurice Merlin’s Black Legion Widow, the museum did not have much to say about the print or the history behind it, hence my compulsion to write this article.

It is my guess that the vast majority of Americans today have no idea what the Black Legion was, but in the 1930s the group grew to be worrisome national headline news familiar to tens of millions. Merlin’s print helps to reveal that part of American history no one can afford to forget. Lamentably, what the print says about America’s not so distant past continues to resonate in our all too uncertain present.

The Black Legion were a shadowy right-wing terror group that operated in Michigan and neighboring states in the 1930s. The Legion boasted six million members, but whatever their numbers, the organization considered it a holy mission to wage war against communists, socialists, anarchists, union organizers, Catholics, immigrants, and every other group the Legion considered undesirable. In their own words, the Black Legion opposed “all aliens, Negros, Jews, and cults and creeds believing in racial equality or owning allegiance to any foreign potentate.” [1]

New Legionnaires made an oath when submitting to the group’s initiation rites. Under cover of darkness an applicant got down on his knees while surrounded by black-robed Legionnaires. As the aspiring member knelt a pistol was aimed at his heart as he recited the official vows; “I will exert every possible means in my power for the extermination of the anarchists, Communists, the Roman hierarchy and their abettors. I further pledge my heart, my brain, my body and my limbs never to betray a comrade and that I will submit to all the tortures that mankind can inflict and suffer the most horrible death rather than reveal a single word of this, my oath.” [2]

Obdurately believing that the administration of Franklin D. Roosevelt was “Marxist” and bent on destroying America, the Black Legion prepared for armed insurrection against the U.S. government. The group enlisted white Southerners who were streaming into Detroit, looking for work in the steel and auto industries.

Operating mostly at night, Legionnaires wore black robes and pirate hats emblazoned with skull-and-crossbones insignia – they implemented their political agenda through beatings, floggings, arson attacks, bombings, and outright murder.

For those reared on Disney’s frothy Pirates of the Caribbean adventure franchise, the Black Legion’s pirate regalia may seem nothing more than buffoonery, but in the 1930s the general public’s view of the iconic pirate was a darker vision shaped by Robert Louis Stevenson’s 1883 novel Treasure Island. Up until 1929 Stevenson’s book inspired no less than twenty-two Hollywood films about ruthless pirates. Surely Black Legionnaires saw themselves as the same type of menacing outlaw buccaneers defying all authority.

Prior to Diego Rivera’s visitation to Detroit, Earl Little, a Baptist minister and supporter of the Black Nationalist leader Marcus Garvey, died of mysterious circumstances. Little had been the target of Ku Klux Klan harassment before, but when the minister moved his family to Lansing, Michigan, they came under Black Legion persecution. When the family home was burned down in 1929, Little blamed the Legionnaires. In 1931 Detroit police reported that Earl Little had been run over and killed by a street car, but witnesses say he was pushed into harm’s way. Little’s son Malcolm, who years later became Malcolm X, insisted his father had been murdered by Black Legionnaires. [3]

Diego Rivera’s murals were based on the Ford Motor Company’s huge River Rouge factory located in Dearborn, Michigan. On March 7, 1932, just six weeks before Rivera arrived in Detroit, thousands of unemployed workers demanding jobs and union representation held what they called the “Ford Hunger March” on the River Rouge factory. Dearborn police and Ford “private security” fired on the unarmed demonstrators, killing five and wounding up to 50; no one was ever charged with the killings. Union organizers suspected that Ford’s private security force included Legionnaire members, moreover, it was feared the Black Legion had infiltrated the union movement itself.

In Furious Improvisation: How the WPA and a Cast of Thousands Made High Art Out Of Desperate Times, author Susan Quinn wrote that, “with the aid of industry leaders opposed to union activity, the legion controlled hiring in certain pockets of the steel and auto industry as well as certain New Deal welfare jobs. Leaders boasted that they ran the entire Federal Emergency Relief Administration in Allen County, Indiana. Indeed, at a time when many were still without work, Black Legion members, even when they came from out of state – all seemed to have jobs.” [4]

On December 22, 1933 the treasurer of the Auto Worker’s Union, George Marchuk, was found murdered in a ditch in a Dearborn suburb. Not long after in March of 1934, the body of John Bielak, a member of the local American Federation of Labor United Automobile Workers, was found dumped at roadside near Monroe, Michigan. Bielak’s killers placed a stack of completed union membership applications beneath the slain organizer’s head, the message being perfectly clear. [5] Union activists believed the Black Legion were behind, not just the murders of Marchuk and Bielak, but the bombing of union halls and homes of labor activists.

After years of terroristic activity, the group’s downfall came about when it murdered an organizer for the Works Progress Administration (WPA). On May 13, 1936, a Black Legion death squad kidnapped thirty-two-year-old Charles Poole from his home and took him on a “one way ride”. Poole, an unemployed auto worker and an organizer for the WPA, was driven to the outskirts of town and shot eight times by a Black Legion triggerman, [6] his crumpled body left at roadside. Police investigating Poole’s murder found a “collection of curious robes and deadly weapons” in the homes of Poole’s neighbors. [7] Dayton Dean, the Black Legion gunman in the slaying, was arrested and made a confession that unraveled the entire Black Legion underground.

Dayton Dean’s admission of guilt revealed that the Black Legion had indeed been recruiting Southern white workers in the auto factories of Detroit to fight in the Legion’s war against unions and communism. Dean testified that the same Black Legion squad that had conspired to murder Charles Poole in May, had also killed Silas Coleman that same month. Black Legionnaires took Coleman, a 42-year-old African American war veteran, into the countryside and made him run for his life before gunning him down. According to Dean, Harvey Davis, the head of the murder squad and chief of the Black Legion organization wanted to “see how it felt to shoot a Negro”.

In an AP story that ran in the June 11, 1936 edition of The New York Sun, it was reported that “The Bullet Club”, a unit of the Black Legion in Pontiac, Michigan, “included on its roles a large number of public officials” and that “the trail of Black Legion terrorism led into three large Detroit automotive plants” where Legionnaire intelligence squads gathered information on union activists who were undoubtedly targeted for assassination. [8]

In the end Dayton Dean’s testimony eventually led to convictions against dozens of Black Legion members. In the Poole and Coleman slaying cases, twelve Legionnaires were found guilty of first degree murder and given life sentences, including Dean himself. Thirty-seven other Legion members were sentenced to prison on charges of conspiracy, attempted murder, and other crimes. As it turned out, Wayne county prosecutor Duncan C. McCrea, the leader of the prosecution in the Charles Poole case, was discovered to be a member of the Black Legion! When this was revealed McCrea stated he had “accidentally” signed a membership card for the group, but Legion defendants in the Poole case swore prosecutor McCrea willingly participated in the fascist group’s chilling initiation rites. [9]

That the state prosecutor in the Black Legion murder trial turned out to be a Legionnaire fanned the flames of suspicion that government trials against the terror group were not so much a series of legal proceedings as much as they were cover-ups. A number of known Black Legion leaders and cadre were never arrested or rooted out of their positions in the private sector, government, and the police. It appeared the fanatical Black Legion, with its long track record of murder and mayhem, had influential friends in high places.

The 1936 Black Legion trials captured national headlines in the U.S. The topic of a homegrown fascist terror organization so gripped the public (the Nazis had come to power three years earlier in 1933) that Hollywood produced two films on the subject. First came the 1936 effort from Columbia Pictures titled Legion of Terror with actor Bruce Cabot (who starred in the original King Kong). A better-known film titled Black Legion was released by Warner Brothers in 1937. The film’s cast included Humphrey Bogart in his first leading role. Bogart played the part of fictional character, Frank Taylor, who was no doubt modeled after the Black Legion trigger-man, Dayton Dean. The film closely mirrored the events that led up to and included the killing of Charles Poole, and ended with the Black Legion killers being convicted in court and sent to prison.

A major flaw in the Warner Brothers film was that it gave the impression the Legion had set their sights exclusively on Polish and Irish immigrants. The reality of the group terrorizing union organizers, communists, and African Americans was not addressed.

Even so, the movie contained powerful scenes, one being Bogart’s character going through the group’s initiation ritual and taking its blood-curdling oath. The film’s most daring scene depicted three industrialists discussing their financial backing of the Legion in order to expand their profits and defeat the union movement.

The Warner Brothers/Bogart film has long been forgotten, but it remains an electrifying indictment of false patriotism, intolerance, and political extremism (the film is available on Netflix).

Maurice Merlin’s Black Legion Widow print was created at a time of increased public awareness regarding fascism. He was a signatory to the original “Artist’s Call” issued by the American Artists’ Congress (AAC), an artist’s organization founded in 1935 for the express purpose of opposing censorship, fascism, and war. Signatories also included the likes of Ivan Albright, Ben Shahn, Edward Biberman, George Biddle, Margaret Bourke-White, Paul Cadmus, Pablo O’Higgins, Alexander Calder, Anton Refregier, Phyllis (Pele) de Lappe, and many others too numerous to mention.

The call was an appeal for all artists to attend the American Artists’ Congress in New York City on February 14, 1936. In part, the call read: “A picture of what fascism has done to living standards, to civil liberties, to workers’ organizations, to science and art, the threat against the peace and security of the world, as shown in Italy and Germany, should arouse every sincere artist to action. We artists must act. Individually we are powerless. Through collective action we can defend our interests. We must ally ourselves with all groups engaged in the common struggle against war and fascism.”

Hundreds of artists from across the U.S., Latin America, and Europe attended the 1936 American Artists’ Congress, including a Mexican delegation that included David Alfaro Siqueiros, José Clemente Orozco, Rufino Tamayo, and Luis Arenal. The AAC mass meeting also featured an exhibition aptly titled America Today. Over 100 works of art where shown, one of which was Maurice Merlin’s Black Legion Widow.

####

UPDATE: I received the following e-mail on 5/14/2014;

“My name is Mary Coulter. I am the granddaughter of Charles Poole who was killed in 1936 by the Black Legion. My grandmother Rebecca was depicted in the art work on your site. In the picture there is a boy next to her, but my grandmother had two girls. So much of the information surrounding those events were slightly off. In your article/blog you also said he was killed on May 13th. He was killed on May 12th and found on May 13th in the morning dead from the night before.

I never saw this artwork before and when I did it made me cry. I am currently doing a little research because I intend to write a book about my grandmother. I want to thank you for your caring about this issue and giving me the opportunity to find this all out. It touched my heart.

I think if you knew my grandmother you would be amazed how that picture captured her sorrow. It’s like the artist knew her. I felt the same sadness from looking at it that I felt from my grandmother when she talked about it. I would love to see it some day. I also would like to put a copy of it in my book, if I ever get to publish it.”

— // —

Footnotes

[1] Page 295. “The Southern Diaspora: How the Great Migrations of Black and White Southerners Transformed America“. James Noble Gregory © 2005.

[2] “The Black Legion Rides” By George Morris. Published by Workers Library – Aug. 1936. Reference found in Chapter II, “The Hood Is Lifted”.

[3] “The Dark Days of the Black Legion” by Richard Bak. Published in Hour Detroit, March 2009. Pg. 1, paragraph 12.

[4] “Furious Improvisation: How the WPA and a Cast of Thousands Made High Art Out Of Desperate Times“. Susan Quinn © 2009. Chapter nine, “It Can’t Happen Here”.

[5] Page 66. “Detroit: City of Race and Class Violence” by B.J. Widick © 1972.

[6] Front page story, The Montreal Gazette. June 4, 1936. “Black Legion Member Confesses Slaying Poole, Names Instigator“.

[7] “Black Legion Rule Broken“, The Bend Bulletin – June 8, 1937.

[8] “Another Plot To Kill Is Laid To Terrorists: Black Legion Executioner Also Supplies Link to Bomb Blast“. AP Wire story, published in The New York Sun, June 11, 1936.

[9] “The Dark Days of the Black Legion” by Richard Bak. Published in Hour Detroit, March 2009. Pg. 2, paragraph 10.