In the Land of the Tlingit

Fortune smiled upon me and I found myself in the land of the Tlingit from June 7th to June 14th, 2015; I made an all too brief journey to Southeast Alaska and witnessed many wonderful sights during my brief sojourn. The indigenous Tlingit, Haida and Tsimshian people all live in the region, but this article will place emphasis on the enduring Tlingit people as I encountered them during my visits to the Alaskan communities of Icy Strait Point, Hoonah, Juneau, and Ketchikan. This essay features some of the photographs I took during my travels.

I am certainly not an expert when it comes to the culture and history of the Tlingit, but I have always had a great affinity for the indigenous of this hemisphere. However, I am writing as a realist painter and printmaker from the metropolis of Los Angeles; I dash off these words as someone who, for a short while, escaped the congested postmodern swamp of L.A. to view another, pristine world.

In the plastic megalopolis where I live, art has degenerated into little more than a voguish commodity, largely disconnected from community and history. Art functions differently in the land of the Tlingit, and we have much to learn from them when it comes to an arts philosophy. This essay is presented in that spirit.

My first stop was Icy Strait Point on Chichagof Island, which in actuality is the extreme outskirt of nearby Hoonah, Alaska’s largest Tlingit village. The Tlingit call their lands, Lingít Aaní, (roughly, “Land of the Tlingit” or “Tlingit Nation”). The meaning of the name “Tlingit” can be interpreted as “People of the tides.” It is not known when they settled the area, but evidence points to their being in the region for at least 3,000 years. Beginning in 1700 the Tlingit were forced from their villages in Glacier Bay by an advancing glacier. They eventually settled in a place they called Xunniyaa, “shelter from the north wind,” which is today’s Hoonah.

The environment at Icy Strait Point is dazzling beyond words; deep blue Pacific waters meet broad pebbled beaches strewn with driftwood, mussel and clam shells. Above the shoreline a lush rainforest dense with cypress and pine trees, ferns, wildflowers, and thick carpets of moss, looms above the sea. Higher up still one finds verdant mountain forests and majestic peaks capped with snow and ice; bear hunt for salmon in the icy rivers and streams.

In the days before European colonization, the Tlingit, like the other indigenous people in the region, lived as fishermen, hunters, mariners, gatherers, and traders in an environment so plentiful that acquiring food did not present a problem. The abundance and variety of food, and the easy access the Tlingit had to it, cannot be overstated. It led to the people having the leisure time to develop a sophisticated art and culture.

By 1912 the place now called Icy Strait Point was transformed into a major hub for the U.S. commercial salmon fishing industry. A huge processing factory and cannery was built at the untouched natural bay, which also served as a dock for the fishing fleet. It would not be until the mid-1990’s that the Tlingit people were able to reassert control over that land.

In 1996 the Tlingit-owned Huna Totem Corporation in nearby Hoonah purchased the old cannery, and in 2001 renamed the land Icy Strait Point. The cannery has been transformed into a museum and retail shops; boating, flying, bicycle tours and kayak adventures are conducted out of the village, which is also home to the world’s largest zip-line. Vendors sell fresh caught crab and fresh grilled salmon. “Eco-tourism” is big in Icy Strait Point; one can book tours that will have you walking through glacier-made landscapes, rain forests, and evergreen forests. There are whale watching tours where Orca and Humpbacks abound. Southeast Alaska’s only on-site brown bear viewing is at Icy Strait.

There are a number of impressive totem poles to be found at Icy Strait Point. Totem poles were, and are, narratives that carry on oral traditions, honor ancestors and sacred animal spirits, and mark social or historic events. They also provide identity, as the Tlingit are divided into two moieties or descent groups: Eagle and Raven. The moieties are divided into clans, and clans are further divided into houses. Each entity has its own history, tales, heroes, and guardian spirits, all of which are carved on the totem poles belonging to each tribal group. Traditionally, totem poles were raised in front of community Tribal Houses.

It might surprise the reader to know that salmon eggs played a role in Tlingit art. Pigments – red, green, white, yellow, brown, were derived from minerals; black was obtained from charcoal or coal. These pigments were ground on stones until they became powdered, and then mixed in stone bowls with a little water and crushed salmon eggs. In European tempera painting, the old masters mixed crushed mineral pigments with water and chicken egg yolk to obtain vibrant, transparent, and long-lasting paints. In the same way, Tlingit artisans mixed their mineral pigments with fish eggs. The fish oil made for a tough and lustrous paint that handled like, well, oil paint, and it was fairly impervious to the elements! By the end of the nineteenth century, commercial paints started to take the place of fish-egg tempera.

Many Tlingit carved and painted to some degree, but when something special was required, an artist of great talent was paid for their skills. Such an artist carried a box full of brushes tipped with soft porcupine hair; brush handles were usually made from carved cedar wood. Up to a dozen such brushes of various sizes were stored in the box, along with other necessary tools like pigments, fish eggs, carved sharpened sticks for drawing, and cedar bark stencils for laying out patterns. Tlingit artists never attempted to shade with their colors, nor did they mix them. While Tlingit art always presented form in a realistic manner, the European understanding of perspective was entirely unknown.

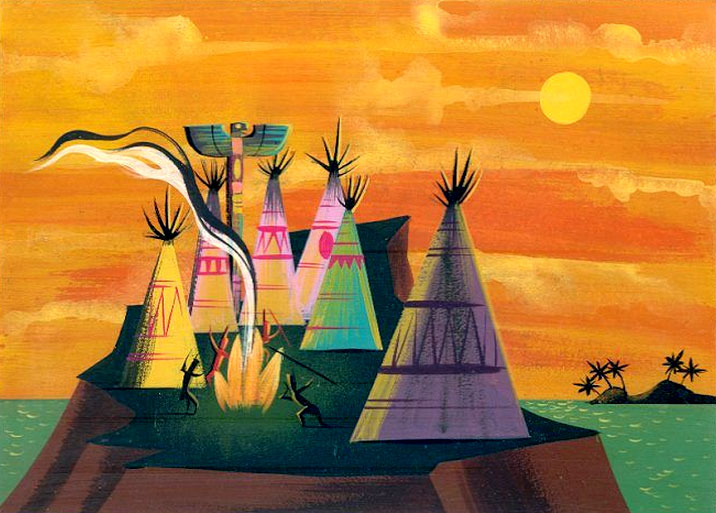

Hollywood movies and cartoons spread the notion that “Indians” lived in teepees next to garish totem poles.

In reality totem poles are a unique art form created only by the indigenous people of the Northwest coastal region, the Tlingit, Haida, Tsimshian, Kwakwaka’wakw, Bella Coola, and Nootka.

Totem poles were never created as religious objects to be worshipped. Europeans came up with the term “low man on the totem pole,” a reference to the order of figures placed on the poles, to describe someone without power or social status. In reality, it was not dismissive for a figure to be placed at or near the bottom of a pole. The multiple figures carved on a pole told a story, but one usually understood only by the clan or family that owned it.

The Heritage Center Native Theater at Icy Strait Point is where presentations of Tlingit history, dance, art and music are made. Constructed as a replica of a traditional cedar plank Tribal House, the theater provides a glimpse into the living traditions of the Tlingit.

Standing in front of the center are two splendid totem poles that were carved by the late Jimmy Marks, who is still widely hailed as a Tlingit master carver whose unique designs are immediately recognizable. Born with the Tlingit name of Jakwteen in 1941, Marks worked in the Hoonah fishing fleet as a fisherman. He became known for his carvings and eventually became a carving instructor. He was fluent in the Tlingit language, and taught it in the Juneau School District Indian Studies Program. Marks passed away in 2009 at the age of 67, but his works continue to inspire.

Icy Strait Point is home to Lisa Andersson (Yak x waan tlaa) and Jeffery Skaflestad (Sei ya Eesh), two impressive artists who create traditional weavings, carvings, drums, and moccasins of the highest quality; they sell their works at Dei L’e.aan, Andersson’s store in the transformed cannery. Mr. Skaflestad has a work table set up in the store where he diligently hand carves traditional wood masks using hand tools. I spent some time talking with the enthusiastic and knowledgeable Skaflestad. Sensitive to my interest, he regaled me with stories on woodcarving, the production of Tlingit armor, and methods of producing the world renown “bentwood box.”

The traditional bentwood box is made from a single cedar plank, shaped and molded through a process of steaming. The boxes are made without a single nail or corner joint, lids for the boxes were similarly produced. The boxes can be elaborately carved, inlaid, and painted or left plain, depending on its intended use. In the old days the wooden cases were used as furniture, shelves, treasure chests, and storage containers. They stored wardrobes, ritual objects, or served as pantries. The boxes were so well constructed that they were even used to cook food. Water in a bentwood box could be brought to a boil by dropping heated stones into the container – just add cuts of salmon!

I had a conversation with a Tlingit woman at Icy Strait Point who, like many locals, is a shareholder in the Huna Totem Corporation. Bright, enthusiastic, and fiercely proud of her heritage, she exemplified all the people I talked to who work in the small town. She told me that collective ownership of the village had brought economic sustainability to her people. Great care had been taken to present the true face of indigenous culture, keeping out most of the cheap, kitschy trinkets in favor of locally made indigenous arts and crafts. She informed me that so far, proceeds from sales made in Icy Strait Point provided a half-million dollars in educational scholarships to Tlingit youth.

Less than a 2 mile walk from Icy Strait Point is its parent village of Hoonah. Commercial fishing and processing still employs many, but the work is seasonal and grueling. The timber “industry” was the second largest industry in Alaska during the 1970s, but when it collapsed, tourism became the economic lifeblood of Hoonah. With a population of around 800 individuals, 80% are Tlingit, and most of them work at Icy Strait.

I was told time and again that Hoonah is the face of the real Alaska. It is a small, working class enclave fully integrated into a magnificent natural landscape. Colorful rustic homes, mom and pop stores and eateries, picturesque harbors, community centers and churches dot the landscape.

American Bald Eagles perch on telephone poles and rooftops; ravens are everywhere, and they are the biggest ravens I have ever seen… in more ways than one. A traditional Tlingit creation story tells us that Raven brought light into the newly created world. I was enormously impressed by the Ravens I saw, and will be drawing them in future artworks.

At Hoonah an extremely important undertaking for the Tlingit is now underway, the building of a traditional Tribal House. The Tlingit have not had such a structure in their homeland for over 250 years. At present Tlingit master carvers Gordon Greenwald, Herb Sheakley, and Owen James are laboring in a workshop next to Hoonah High School, carving totem poles and other items for the project. It was my intention to visit the workshop, not just to assess the endeavor’s progress, but to learn a few things from the committed indigenous artisans. As fate would have it, their workshop was closed when I arrived in the late afternoon, but I can still tell you what I know of their work.

The Hoonah Indian Association reached an agreement with the U.S. National Park Service (NPS) to build the 2500 square foot Tribal House on the shoreline of Bartlett Cove in Glacier Bay National Park, the ancestral homeland of the Tlingit. Construction has already begun and it is scheduled to be completed by the summer of 2016, just in time for the centennial year of the NPS.

The large plank house has been called Xúna Shuká Hit by tribal elders, which roughly translates into “Hoonah House of Ancestry.” The House will represent both the Eagle and Raven Moiety, and will provide a center for sacred ceremonies, tribal knowledge, workshops, and meetings. It will also be open to park visitors who will have the opportunity to learn about Tlingit culture and history firsthand.

To reach the new Tribal House, one must first cross the actual Icy Strait passage that separates Chichagof Island from Glacier Bay National Park. The region is remote, and all travel is done by boat or plane. On the dedication day in the summer of 2016, the Tlingit and their many friends will arrive at the site in dug-out canoes and ferryboats from wherever they live. They will come singing and drumming to usher in a new chapter in their history.

Standing in front of Hoonah High School are two enormous and intricately carved totem poles created by Tlingit brothers Mick and Rick Beasley. Brightly painted in red, green, white, and black, the traditional totems at the school are carved in Western Red Cedar; however, they have a modern touch to them. Though based in Juneau, the works of the Brothers Beasley have graced a number of public places, including museums throughout the region. Rick began to carve at the age of eight when he was inspired by his teacher, the aforementioned Jimmy Marks.

Juneau is the capital city of Alaska. Named after a gold miner from the late 1800s, it is the second largest city in the state with a population of around 32,000. It was impossible not to notice the public indigenous art, or the apparent pride the city has regarding its indigenous history. For instance, the outer wall of Juneau’s City Hall is painted with a beautiful mural that portrays the spirit animals Raven, Bear, Frog, Eagle, Whale, and Wolf that have been so important to First Nations people of the Northwest Coast.

Painted by local artist Bill Ray Jr. in 1988, the mural depicts the Haida creation story of Raven discovering man, and so is titled Raven Discovering Mankind in a Clam Shell. I certainly cannot say that officialdom in Los Angeles has extended that level of respect to the original people of the L.A. basin, the indigenous Gabrieleño-Tongva.

Juneau is home to the recently opened Sealaska Heritage museum at the Walter Soboleff Center, in fact I visited the museum just one month after its grand opening on May 15, 2015. It was founded by the Sealaska Heritage Institute (SHI), a nonprofit organization of the Tlingit, Haida and Tsimshian people of Southeast Alaska. The museum’s mission is to showcase indigenous art of the region, but also to rejuvenate it while nurturing future generations of artists. It houses an exhibit space, archives for its extensive collection of art, artifacts, and ephemera, a carving shed for the production of totem poles and other carved items, a gift shop were high-quality indigenous art and crafts are sold, rooms for conducting classes and lectures, and office space for the SHI.

During my visit, the Sealaska Heritage museum was exhibiting Tlingit armor, both antique and contemporary. Helmets were usually constructed in two pieces, the collar and the actual helmet, which was carved with supernatural beings, animals, or clan symbols. Collars were created from hard, dense wood burls of spruce, alder, or yew that were made into planks and bent into a circle through steaming. The collar was closed at the back and tied off with a leather thong. Two eye-hole notches were carved into the top of the collar, allowing a warrior to see out, breathing holes were provided, and an internal nose indent was carved. The warrior wearing the collar could bite down on an internal loop of spruce, which acted as a mouth guard but also secured the helmet.

When taking a blow to the head, the warrior could lift his shoulders, causing the helmet to strike the collar rather than his head. The War Helmet in the foreground of the picture shown above, was carved from yew wood in 2014 by Tlingit artist Tommy Joseph. It depicts a female warrior, which was not entirely uncommon; historic accounts mention women that not only engaged in battle, but directed attacks. The woman on the helmet has eyes of inlaid abalone, and is decorated with strands of human hair. She is depicted wearing a labret, or lip ornament. The labret was a sign of high rank not worn by all, but it was worn exclusively by women. At a very young age, a girl’s lip was pierced with a copper wire, later replaced by a wooden skewer, and by thirteen she began wearing a labret carved of wood.

A Tlingit helmet served the practical purpose of protecting its wearer, but with its fearsome carvings of animals or supernatural creatures, the armor was clearly a method of intimidation. The Russians that attempted to conquer the Tlingit during the 1804 battle at Sitka, reported their musket balls being deflected or stopped by the helmets. The Tlingit also wore body armor made from hardwood slates and elk hide that could stop arrows or deflect blows. Warriors were armed with bows and arrows, a variety of clubs, as well as daggers and lances they fashioned from native copper. As trade with Europeans increased, steel replaced copper; Chinese coins were sewn onto leather shirts to make a type of “chain-mail.” But firearms eventually made Tlingit armor obsolete, and the War Helmet evolved into the clan hat at around 1850.

The architectural design of the Sealaska Heritage museum pays homage to ancient ancestors. The huge traditional sculptural motifs constructed of red painted metal and mounted on the cedar façade of the museum’s entrance, represent the “Greatest Echo,” a supernatural being from Haida mythology. The sculpture was created by artist Robert Davidson, who is of Haida and Tlingit descent. In the museum foyer you first see a monumental carved and painted wood house front, of the type that once faced the cedar timber and plank communal village houses that Southeast Alaska indigenous nations made long ago.

In times past such houses were built along the banks of rivers or the ocean, with each facing the water and housing between 20 to 50 individuals. The museum’s 40 ft. wide house front was created by Tsimshian artists David Albert Boxley and his son David Robert Boxley; the carving’s central design tells the Tsimshian story of the earth, and Am’ala, The Man Who Holds Up the Earth. Surrounding that motif are designs representing all the tribes of Southeast Alaska.

But the Boxley mural-like house front is actually an entryway to another room. You have to bend down to go through the small door located in Am’ala’s belly, but it opens into the Shuká Hít (Ancestors’ House), a replica of a traditional clan house that serves as the museum’s public auditorium, performance space, and lecture hall where video can also be projected.

The museum’s glass awnings encircling the building are etched with formline designs created by Northwest Coast indigenous art expert Steve Brown. Formline is the spacial, proportional, and aesthetic basis for all Southeast Alaska/Northwest Coast indigenous art. Remarkably, when the sun shines through Brown’s awnings, the etched glass designs cast their shadows onto the sidewalk, painting in light the ethereal presence of ancient ancestors. All in all these architectural flourishes contribute to a stunning museum, a true gem among America’s art institutions.

Dr. Walter Soboleff was Tlingit and a civil rights activist who fought for indigenous rights and the revitalization of his people’s culture. He died in 2011 at the age of 102, and the museum was named after him. The ceremonial Clan hat shown below belonged to Soboleff, it happened to be one of the items on display during my visit. Soboleff’s clan was the L’eeneidi of the Raven Moiety, who were referred to as Dog Salmon. The oral traditions of the L’eeneidi say that they migrated down the Stikine River until they reached the coast and settled in Angoon and later Juneau. Their Dog Salmon name and crest was acquired in a supernatural encounter.

In 1982 the Sealaska Heritage Institute started a biennial festival called Celebration, a mass gathering of the Tlingit, Haida, and Tsimshian nations where their art, culture, dance, oral traditions, and music are shared, not just with one another, but with the entire community of Juneau and beyond. When the festival first began in ’82 it attracted 150 participants, today it attracts many thousands. The upcoming June 8, Celebration 2016 promises to be the largest gathering yet.

Ketchikan was the last stop on my journey. Long ago the Tlingit named a favorite salmon fishing creek in the area the “Thundering Wings of an Eagle,” or “Ketchikan” in their language. When Europeans founded a town there in 1885 they named it Ketchikan. It had been an important fishing village for the Tlingit, and under European colonization it became known as “The Salmon Capital of the World” due to the massive industrialized fishing industry. Today fishing is still important, but tourism has become the number one industry, and Ketchikan Creek is now a favorite destination for tourists. If I needed any reminder of the city’s origins, I heard Tlingit spoken on the streets.

Surrounding Ketchikan is the Tongass National Forest, the largest national forest in the U.S. It is named after the Tongass group of Tlingit who originally inhabited Ketchikan. At the city’s downtown waterfront dock, a large bronze sculpture titled The Rock welcomes visitors, setting the pace for the Ketchikan experience. In 2007 the city issued an artists call for public art. Artist Dave Rubin won the commission for his proposed bronze monument, whose seven figures would serve as archetypes for the city’s history. Assisted by sculptors Terry Pyles and Judy Rubin, the monument was completed and publicly unveiled on July 4, 2010.

Standing at the top of the sculpture is Chief Johnson, a famous leader of the Ganaxadi Tlingit of the Raven moiety from the Tongass group. At the base of the statue sits an indigenous woman who plays a drum while singing her song of Ketchikan. According to artist Dave Rubin, that song is a historical narrative of Johnson and the figures gathered around him: a logger, fisherman, miner, aviator, and European pioneer woman.

Ketchikan is known for its Saxman Native Village and Totem Park, home to a comprehensive collection of Tlingit totem poles and an indigenous carving center where Tlingit artists continue the tradition of sculpting their narrative pole sculptures hewn from live wood. But here I would like to focus on a lesser known treasure, a unique piece of Ketchikan public art called the Yeltatzie Salmon. Jones George Yeltatzie (1900-1976) was born in Howkan, Alaska. He was a full-blooded Haida and belonged to the Double Fin Killer Whale clan. He settled in Ketchikan in 1935, and though he worked as a commercial fisherman until his retirement, he gained renown as a master totem carver. As a child he learned how to carve from his father George, who was also an accomplished totem carver.

In 1963 Yeltatzie received a commission to create a public art piece from the Tourism Committee of the Ketchikan Chamber of Commerce; the art was intended as a tourist attraction that would be installed at Ketchikan Creek. Yeltatzie carved and painted, in the traditional manner, a red cedar sculptural depiction of a 10-foot long king salmon. The carving was so impressive that it was displayed in a traveling exhibit for more than a year before it was finally situated at the creek. It was placed next to the city’s Park Avenue Bridge near Ketchikan Creek’s famous “Salmon Ladder,” where the fish annually struggle upstream to spawn.

Vandals twice attacked Yeltatzie’s sculpture. The last time, almost 30 years ago, it was ripped from its pedestal and thrown into the creek where it suffered extreme water damage. Every effort was made to repair the sculpture before it was reinstalled, but alas, by 2011 Jones Yeltatzie’s mighty king salmon had almost totally rotted away and the city took it down.

In 2012 the Ketchikan Public Art Works/Arts Council issued an artist’s call for an artwork to replace Yeltatzie’s salmon. Local artist Terry Pyles won the commission for his concept titled Yeltatzie Salmon – a giant iridescent mosaic covered sculpture of a salmon to honor Jones Yeltatzie. Pyles, a realistic painter who also creates sculpture in wood, and metal, helped create The Rock sculpture that greets visitors at the Ketchikan waterfront. His Yeltatzie Salmon was dedicated in a well attended public ceremony and unveiling on July 4, 2013.

Terry Pyles’ Yeltatzie Salmon is affixed to a concrete post on the rocky shore of Ketchikan Creek. The sculpture’s multi-colored mosaic tiles flash in the sunlight; the silver fish radiates against the intense green of the creek’s vegetation. The endless sound of babbling waters creates a soothing and contemplative backdrop for Pyles’ creation. When the creek’s waters overflow its banks and the sculpture’s post is enveloped in rushing torrents, the colossal salmon appears to be struggling upstream to spawn. Jones Yeltatzie would be pleased.

As a sidebar to this story I have to mention that I did some snorkeling at Mountain Point in Ketchikan. Long ago I trained with the Professional Association of Diving Instructors (PADI) when I took up scuba-diving in the waters of Southern California. I found the waters of Ketchikan not much colder than deep water diving in California, and with a full body, thick neoprene wetsuit I was more than comfortable. When snorkeling I saw a number of sea creatures that were new to me, like Alaska’s giant Sunflower Sea Stars, and nearby a pod of Humpback Whales were breaching while American Bald eagles flew overhead.

Snorkeling in Ketchikan drove home two points for me. First, diving in Alaska’s waters was magical; few undertakings could so quickly disabuse big city dwellers of their being the “rulers” of nature, nor affirm the spiritual beauty of Mother Earth.

To be enchanted by nature is the real key to understanding the indigenous art of Alaska, and the experience made it clear why the indigenous people of the region have an unalterable reverence for the natural world.

The appreciation for indigenous art coming from non-Native people in Alaska is impressive, it might be newly found, but it is nevertheless firmly established and growing. I must juxtapose this phenomenon to a very different story that unfolded in Los Angeles in April of 2010, regarding the building of LA Plaza de Cultura y Artes cultural center, a museum in downtown L.A. dedicated to Mexican-American heritage.

When construction for the museum began in 2010, the 19th century graveyard of nearby La Placita Church was discovered and the remains of 118 individuals were removed. More desecration than removal, torsos had their limbs and skulls torn away and the remains were placed in bags and buckets for storage at the L.A. County Museum of Natural History. LA Plaza administrators said they had been informed that the old cemetery had closed and moved in 1844, and that no indigenous people were buried there… until indigenous activists produced burial records proving that some two-thirds of the nearly 700 people buried at the cemetery were Gabrieleño-Tongva.

Furthermore, the Gabrieleño-Tongva pointed out that the area under excavation was Yangna, their largest village when the Spanish arrived in 1769. In other words, it was a sacred site for the tribe and a significant archeological find for the scientific community. The California State Native American Heritage Commission asked that excavations for LA Plaza de Cultura y Artes be stopped, and dozens of indigenous peoples held protests to that effect.

On January 13, 2011, indigenous people held a vigil at the construction site, hanging offerings of sacred sage to their ancestors on the chain-link fence around the cemetery. It was all to no avail. Gloria Molina, a Democratic Party politician and then L.A. County supervisor and brainchild behind the museum, did not want any negative publicity to stop the April 9, 2011 grand opening of the museum. When that official opening party occurred, dozens of indigenous people protested outside.

Finally, in April of 2012, the remains of the indigenous dead were returned to the graves from which they were robbed; an ornamental granite plaque notes their presence. The historic cemetery is now located on museum property in what LA Plaza de Cultura y Artes calls a “respectful memorial garden.” The indigenous people of Juneau have the Sealaska Heritage museum, and the City of Los Angeles begrudgingly gives the Gabrieleño-Tongva a granite plaque. So much for forward-thinking “liberal” L.A. and its “enlightened” cultural institutions.

In the Tlingit, I found a people ablaze with creativity and artistic spirit, they understand art as a means to connect with a respected past and to assure the continuation of a beloved culture well into the future. Tlingit art does not exist to shock or alienate, but to uplift, stimulate historic memories, educate, and unify the people; to the Tlingit these aspects of art go hand in hand with an appreciation of craft and beauty.

Such integral facets of art have been altogether rejected by postmodernism. The result being a contemporary art largely reduced to vapid kitsch without elegance, refinement, meaning, or even a tenuous connection to the wider society. The very idea of “craft” has flown out the window. Postmodern artists wear their alienation from the people as a badge of honor. Art has gone belly up. Its worth is defined only by its exorbitant price tag.

An “appropriated” image or a video of someone in the act of vomiting is as good as the ancient Greek sculpture of Laocoön or Michelangelo’s Sistine Chapel frescoes – or so we have been told. How refreshing and invigorating it was not to encounter such nonsense in the wilds of Alaska. By viewing the indigenous art to be found there, artists living in the postmodern blight of the big city might rediscover the real power of art, and what it means to once again, consciously engage with people, community, and society.