That Article or Page No Longer Exists...

Instead check out the latest blog posts below or three random blog posts further down.

Latest Additions to the Blog

AI, the end of Illustration art

I recently came across an illustration of Elon Musk published on a popular news and commentary website. The credit for the likeness read “Image generated

Frida Kahlo and The Dream

The culture vultures have descended. On Nov. 20, 2025 Sotheby’s New York auctioned a 1949 self-portrait by Frida Kahlo. It is titled El sueño (La

Luigi’s Circle Jerk Army

On April 13, 2025, the antediluvian punk rock band from Los Angeles, the Circle Jerks, performed at the Coachella Valley Music and Arts Festival. Singer

Three Random Blog Posts

Lion of the Desert

As a rational human being, a humanist and an artist, I offer my heartfelt sympathies to the families and loved ones effected by the terror

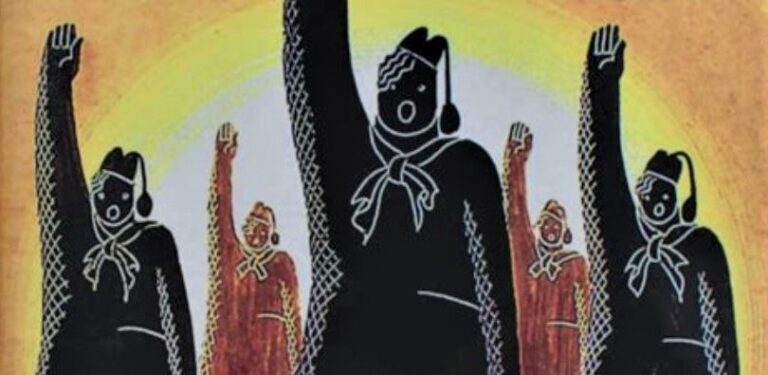

Back To The Futurists

The Italian Futurists had an obsession with all things modern, the city, the automobile, the plane. They turned their backs on the past and set

The Bush Bust & Free Fall

The National Guard Association of the United States commissioned a life-sized portrait bust of President Bush from famed artist, Charles Parks, who for the last