His Majesty King Mob

“One thing is certain. King Mob never wanted to find themselves here, in the house rag of cultural consumption, let alone locked away in Tate’s permanent collection. But these posters and magazines are just detritus, the record of past struggles. In the present day, the real action is elsewhere.”

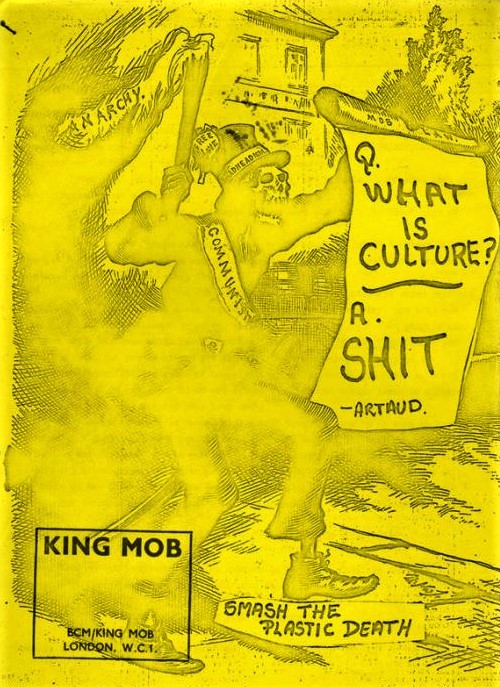

So writes author Hari Kunzru in The Mob Who Shouldn’t Really Be Here, an article for the Tate Britain publication, TATE etc., on the subject of a minuscule collective of English radicals from the 1960s who took their name from the 1780 Gordon Riots of London. During that long-ago uprising, London’s Newgate Prison was destroyed by the rampaging multitudes, and left on its walls was a daub that credited the destruction to “His Majesty King Mob.”

I need not recount the chronicles of King Mob as it reared its ugly little head during the turbulent 1960s, suffice it to say the rebel faction left its mark and Kunzru’s article recounts that history well enough, save for one bothersome fact. Kunzru wrote about the Mob as though it were a prehistoric fossil preserved in amber, when in fact some of its surviving cadre still publish foul-mouthed hair-raising tirades designed to give elites apoplexy.

But Kunzru was correct in noting that King Mob would have wanted absolutely nothing to do with a “cultural mausoleum” like the Tate, since the Mob was, and continues to be, opposed to art altogether, considering it “the commodity which helps sell all the others.”

The question is not why King Mob railed against the grotesqueries of an “outrageous society,” but why Tate Britain thought it essential to include King Mob ephemera amongst its collection of works by Damien Hirst and Tracey Emin.

An archive of King Mob’s subversive printed materials has recently been acquired by Tate Britain, and several anti-art collage works by the King Mob collective are now included in the Tate Britain’s Collage Montage Assemblage exhibit which began at the museum in July, 2008. This is indeed a conundrum, especially in light of the Mob’s unambiguous views regarding art as expressed in a recent statement from them:

“A master of irony and word play, would Duchamp have savored the irony of seeing his Urinal hailed as the most important single contribution to the evolution of modern art by cultural pundits? Unfortunately he would most likely have been flattered. The ‘Urinal’ is now Tate Modern’s altar piece surrounded by a culturally beatified host of imitators.

One wonders what effect a gesture like smashing the urinal would have in the media, on decrepit youth and the avant garde (rather arriere garde) of the cultural establishment, especially if accompanied by a coherent explanation. We are almost tempted, but the thought of the ensuing court case, accusations of cultural vandalism equivalent to the burning of the books, even a prison sentence and certainly a crippling fine for having destroyed a priceless work of art when the aim of the original piece was to debunk any such pretensions, is enough to deter anyone.”

I understand King Mob’s observation that Duchamp’s ‘Urinal’ is nothing more than a urinal transformed into an “altar piece” by the Priests of Postmodernism, what I cannot understand is the Tate Britain embracing the Mob’s incendiary and volatile gesticulations as “art.” I suppose the Mob gets the last laugh by bringing some clarity to the situation when averring the following:

“Where anti-art as an essential part of a modern revolutionary critique was once proclaimed loudly, the simple realization that art is nothing but a consumer appendage or that popular culture is now inseparable from advertising in an utterly commoditized social life far more dire than in the late 1960s… has again been reaffirmed.”