The LACMA Train Wreck

On November 23, 2009, Bloomberg News filed a report titled “Koon’s $25 Million Dangling Train Derailed by LACMA Shortfall.” The story covered the now delayed collaboration between the Los Angeles County Museum of Art (LACMA) and artist Jeff Koons, whose monumental “sculpture” titled Train, LACMA continues to insist will be erected at the museum’s entrance.

With a projected price tag of $25 million, the work by Koons – if undertaken – will be one of the most expensive public art projects ever to be mounted. However, the collapsing economy continues to incapacitate museums and galleries across the U.S., and LACMA is no exception.

In a Nov. 21, Los Angeles Times article titled “Los Angeles County Museum of Art is hard hit by recession“, writer Mike Boehm reported that the museum’s endowments and donations shrank from a total of $129.7 million in 2007-08, to $29 million in 2008-09, a stunning loss of over $100 million!

As a result LACMA has pushed back plans to build and install Koons’ Train until 2014 at the earliest, as the museum simply does not have the required financial resources to construct the ridiculous thing.

The Bloomberg article quoted LACMA’s associate vice president for communications and marketing, Barbara Pflaumer;

“We wouldn’t do it unless someone funds it; someone has to write us a check. This is a very tough economy. (….) The train is something on our to-do list. There’s no question we’d like it to happen. It’s a question of whether we can make it happen.”

Some things should just not be made to happen. On more than a few occasions I have inveighed against Koons and the Director of LACMA, Michael Govan, so I will not bore you stiff by reiterating critiques already made – though a reading of past fulminations would provide some necessary background to this story. Mr. Govan has persistently worked at making the Koons project a reality, but one really has to ask – why? Is it that Govan, LACMA’s Board of Directors and wealthy contributors, actually believe Koons to be the preeminent artist of our time? I shudder to think that is so, but no other conclusion seems possible.

Considering LACMA’s shaky finances during this exceedingly difficult economic period, not to mention the hard luck millions of Americans have fallen upon – who can sympathize with squandering so much money on something so frightfully banal and stupefyingly crass? That LACMA intends to commission and install Koons’ Train to the tune of $25 million, is analogous to proposing that our great libraries be emptied of the classics and filled up with romance novels, pulp fiction, and comic books.

There is another aspect to this tale. On a surface level the Koons Train sculpture bears a close resemblance to two other train artworks; these were created in Scotland and Brazil respectively, well before Koons drew up his Train proposal for LACMA. The Scottish and Brazilian train projects are little known in the United States, so a close examination is in order. Comparing the three train projects, one is not so much left with the suspicion that Koons simply lifted his idea from others, as one is given insight into just how much Koons’ Train is totally uninspired and lifeless.

Scottish artist George Wyllie produced a public art installation and performance piece in 1987 titled, Straw Train. Wyllie paid tribute to the history of the Scottish Railway industry by building a full-sized steam engine locomotive out of straw. The work of building an accurate replica train from straw took place at the abandoned Hyde Park Works in Springburn, Scotland, where the nation’s first private locomotive company built steam engine trains for export and domestic use. At its peak the massive train factory covered 60 acres, employed 8,000 workers, and constructed 600 trains a year.

Upon completion, Wyllie’s Straw Train was paraded through the streets in a public procession that followed the route real engines would have taken as they were transported to the shipping docks at the Finnieston port. Once at the port, Wyllie’s Straw Train was suspended from the famous Finnieston Crane, a prominent landmark in Glasgow, Scotland, celebrating the city’s industrial heritage. The Finnieston Crane once loaded untold numbers of the massive locomotives produced at the Hyde Park Works onto transport ships for export. Wyllie’s whimsical sculpture remained suspended from the massive crane for several months as part of the Glasgow Garden Festival of 1988 – attended by some 3 million people.

Following the Glasgow Garden Festival, Straw Train was transported back to the Hyde Park Works in Springburn, where it was set ablaze in a public performance. As flames consumed the dry straw, the sculpture’s metal armature was exposed. When the straw was reduced to ashes and only the metal framework remained, one could plainly see that the artist had incorporated a giant metal question mark into the structure – the artist’s emblematic signature but also a query as to the fate of Scotland’s industrial past.

Straw Train had great resonance for the people of Scotland, making direct reference to their proud history and accomplishments even as the artist posed relevant questions about capitalist economic restructuring and the resultant deindustrialization of society. Conversely, Koons’ work is altogether bereft of social import. It fails to challenge or advocate and does not lead to any meaningful introspection, it has no connection to history; in fact it makes absolutely no claims about anything whatsoever, it simply exists, like the faux Matterhorn Mountain at the Disneyland theme park in Anaheim, California. Koons said of his project; “It’s very visceral. It gives us a sense of this kind of power and energy and the preciousness of this moment of life.” Just what exactly does that mean? Such a statement could be used to describe a pile of junked automobiles – if one’s intent was obfuscation. And what can be said of those at LACMA who find profundity in Koons’ gobbledygook explication?

The popular theme park Mundo A Vapor (Steam World) in Canela, Brazil, incorporates a life-sized steam engine train into its entry way in much the same manner that LACMA looks forward to doing – although only L.A.’s museum has pretensions of presenting “high art.”

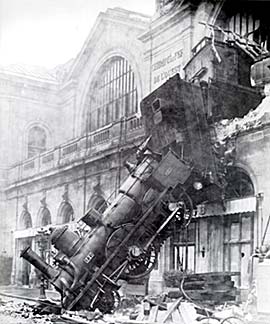

Canela is a small picturesque city situated in the mountainous region of the state of Rio Grande do Sul, Brazil. Mundo A Vapor is a charming theme park that presents the history of the steam engine, from toys and crafts to productive technology and train transport – it offers informative displays and fun for the whole family, including a miniature train kiddy ride. The theme park is internationally famous for its unconventional entrance façade which makes use of a full-scale replicated steam engine locomotive; a life-size reconstruction of the 1895 train crash in Montparnasse, Paris. The train’s steam powered whistle actually screams on the hour as the train’s chimney discharges billowing clouds of steam to the great delight of tourists, who crowd around the locomotive to take still photos and shoot videos (one such amateur video can be viewed on YouTube).

Chances are only a handful of people know, or care about, the name of the architectural engineer commissioned to design the entrance façade at Mundo A Vapor, and it is my educated guess that the professional was not awarded $25 million. It never occurs to the jovial tourists flocking around the steam engine behemoth – marooned at the theme park doorway like a beached whale – that the tableau was designed by a specialist; that detail is simply irrelevant. To the cheerful multitudes the train façade offers only a fantastic setting for photographs, nothing more, and that is how it should be seen. If those gathered around the train were told that the locomotive was in fact a majestic sculpture of paramount importance, created by a modern master of unsurpassed vision, and that the objet d’art was worth ten of millions of dollars, they would most likely laugh out loud at the preposterous tall tale.

So then what precisely is the difference between the locomotive at Mundo A Vapor and Koons’ Train? Aside from the fact that the Brazilian train does not spin its mighty iron wheels as the LACMA train is being designed to do, the one and only distinction is that LACMA’s Train is linked to brand Koons; declared by inordinately powerful individuals with exceedingly bad taste to be the finest high-end commodity available on the “art market” today. Museum culture is undergoing a transformation where a sham populism guided by market forces is quickly becoming the norm. Some museums are developing into zones for the appreciation of the kitsch, shallow, and gaudy; there is no better example of this than the relationship LACMA has cultivated with the likes of Koons.

The train at Mundo A Vapor is a real crowd pleaser to be sure, and undoubtedly millions have stood beside it to have their pictures taken, but does anyone think of it as a magnificent artwork? Would anyone in their right mind say of the train; “It gives us a sense of this kind of power and energy and the preciousness of this moment of life”? Well… perhaps some would, just as they might say the same thing about that thrilling roller coaster ride at Disneyland’s Matterhorn Mountain – but that does not add up to momentous art or a thoughtful art experience.