Who was Tomata du Plenty?

“Do plenty people go for Tomata, yes,

But he just goes for that special girl… who says ‘NO!'”

Lyric from Adult Books, by L.A. punk band X.

The question of “Who was Tomata du Plenty?” was first broached by the Los Angeles punk band X, in their 1978 song Adult Books. The lyrics remain a mystery, even to veterans of the original Los Angeles punk scene. The lines in the song were an esoteric reference to Tomata, the front man for the techno-terror punk outfit the Screamers, who counted amongst their repertoire angst-ridden songs like, 122 Hours of Fear, Punish or be damned, Magazine Love, and Nervous.

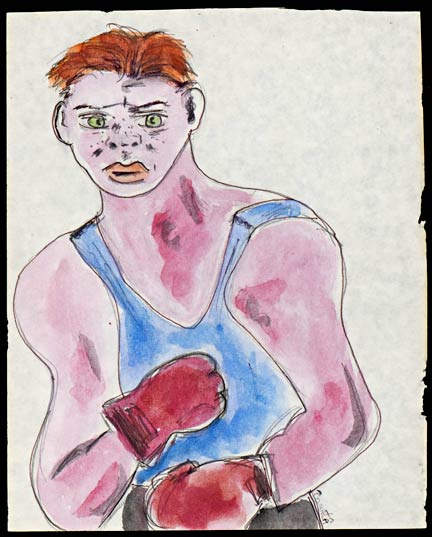

As for the query regarding Tomata’s identity, answers might be found – to some extent – in a surprising exhibition at the Georgia Museum of Art, Boxers and Backbeats: Tomata du Plenty and the West Coast Punk Scene. The show is an examination of Tomata’s naïve paintings in the context of the original 1977 L.A. punk rock milieu, and having been one of the earliest admirers of Tomata and the Screamers, it is a unique honor for me to have some of my drawings included in the exhibit.

For my own sensibilities, there was no greater punk band in L.A., or anywhere else, and I attended most of the Screamers’ L.A. performances. But in spite of their brilliance the group never recorded or released a record. Many of my punk associates referred disparagingly to the Screamers as an “art band,” an appellation not entirely incorrect. Ironically, filmed performances and bootlegged recordings of the ensemble have been appearing on YouTube, where more people have been exposed to their artistry then ever saw them in live concerts.

On stage with the Screamers, Tomata contorted his face and body as if they were made of rubber, evincing all the bewilderment and anxiety of a media overdosed society. He could pace the stage as though stricken with rigamortis, or run about like a mischievous imp. He often resembled a panic-stricken marionette that had suddenly become self-aware, but nervously sensed some unseen master was pulling his strings.

Tomata was the consummate punk front man, the very picture of alienation that marked punk in the late 1970s. He bore an uncanny resemblance to Egon Schiele, that early 20th century Austrian Expressionist painter who delighted in symbolically poking his fingers in the eyes of the bourgeoisie. On stage Tomata had no inhibitions, his every move was pure madcap theater, but it was the sinister showbiz of some demented North American funfair, and Tomata was the lunatic carny in charge.

Of all my recollections of Tomata and the Screamers, the following are the most vivid. Midway through performances of their song Eva Braun, the band members would walk off the stage. Having eschewed guitars in favor of synthesizers, they let the electrophonic instruments and computerized modules drone on in their absence. As a stark evocation of mindless hero worship the song was chilling enough, but in the context of the song’s lyrics, when the band left the audience to the machines another narrative emerged; either technology is liberatory, or it is an adjunct to tyranny. During their very last performance (Whiskey a Go Go 1981), the band used banks of onstage video monitors to great effect, displaying video taped scenes that startled and mesmerized the audience. Considering that video cameras and VHS cassette players were as yet unknown to most people, or that video rental stores did not yet exist… the Screamers introduced us to the future that evening.

Few in L.A.’s original punk scene were aware that Du Plenty’s adroitness at theater came from an earlier time. At the zenith of San Francisco’s Flower Power movement he visited the Haight-Ashbury district of the city in 1968 as a twenty-year-old and became a member of the psychedelic drag queen troupe, The Cockettes. Founded by the transplanted New Yorker George Harris (1949-1982), the ensemble was extremely influential, helping to usher in not just the modern Gay Liberation movement, but Glam Rock as well. In 1969 Du Plenty moved to Seattle, Washington, where he founded a similar street performance group, Ze Whiz Kidz. A rare film clip from 1971 shows Du Plenty and his ensemble (including Melba Toast, who was to become Tommy Gear in the Screamers), performing at Seattle’s University District Street Fair. This direct connection to the underground countercultural movement of the late 1960s cannot be discounted.

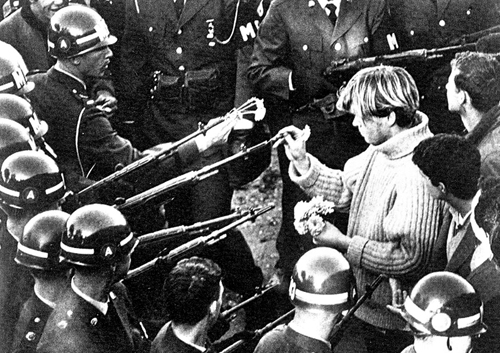

In 1967 George Harris had joined some 70,000 Vietnam war protestors when they marched on the Pentagon to “Confront the War Makers.” Some 2,500 federal troops bearing rifles with fixed bayonets surrounded the Pentagon and blocked demonstrators from entering it. Counterculture activists like the Yippies said they would “Levitate the Pentagon” with chants and exorcism rites, causing the building to rise into the air and vibrate until all of its demon spirits were expelled – thus ending the war. The eighteen-year-old Harris was photographed putting flowers into the rifle barrels of immovable Military Police. Taken by photographer Bernie Boston for the now defunct Washington Evening Star, the photo became emblematic of the ’60s antiwar movement.

After the Pentagon action Harris moved to San Francisco and underwent a metamorphosis. He changed his name to Hibiscus and fell in with a vanguard circle of flamboyant, LSD dropping, hippie drag queens that performed gender-bending free theater on the streets; Hibiscus would eventually organize the entourage into The Cockettes. His ideas concerning street theater as a liberatory vehicle were no doubt inspired by the Diggers, the radically egalitarian and amorphic collection of revolutionaries that were at the core of San Francisco’s ’60s hippie counterculture. It was a co-founder of the Diggers, Peter Berg (1937-2011), that coined the term “guerilla theater” to describe the type of subversive performances that merged art and politics on the streets – turning active and unwilling participants alike into “living actors.”

French filmmakers Céline Deransart and Alice Gaillard made Les Diggers de San Francisco, a documentary on the Diggers that was broadcast on French television in 1998. If you think you know anything about the Haight-Ashbury scene of the mid to late ’60s, the film will quickly disabuse you of that notion. In the Haight, Diggers successfully created free stores, free medical clinics, free food programs, free housing, and free cultural events to show that mutual aid was a viable alternative to capitalism. The Digger creed was to live as though the revolution had already happened. The entire 1 hour and 20 minute film can be viewed on the Digger Archive website. Also found on the website is a clip from the 2001 documentary The Cockettes, produced by filmmakers David Weissman and Bill Weber. It presents statements from associates of Hibiscus, the gay hippies of the Cockette house, and fellow communards of the 300 or so radical communes that sprang up in the San Francisco bay area by the early 1970s.

Tragically, Hibiscus was among the initial casualties of AIDS, which was a mysterious ailment at the time. When he died in 1982 at the age of 33, a New York Times headline referred to the disease that struck him down as a “Homosexual Disorder.” The media generally referred to the malady as GRID, or “gay-related immunodeficiency.” Hibiscus was also one of the very first individuals the media identified by name as having succumbed to the illness.

The now little understood and esoteric histories of San Francisco’s radical alternative culture certainly made a mark on my generation, it seems that was something Tomata du Plenty and I had in common. I passed through Haight Ashbury as a 14-year-old, an experience that validated my own journey as a dissident artist, and years later I found myself entangled with L.A.’s original punk explosion.

But Tomata transmuted his experiences with 60s radicalism into the aural punk assault of the late 70s. After founding the Tupperwares, which essentially was a glam rock spin-off of Ze Whiz Kidz, the band moved to Los Angeles in 1976 and morphed into the Screamers. At the time, if any L.A. punk knew of Du Plenty’s role in the 60s they kept quiet, given that punks went into conniption fits at the very mention of “hippie” (listen to the 1978 single Kill The Hippies by the Deadbeats, one of L.A.’s original punk bands).

In an interview that appeared in the Summer 1978 issue of Slash Magazine, Du Plenty spoke about his role as a performer; “I ask myself, ‘is it possible to be all things to all people?’ Yes. It is my fate to assimilate the inner turmoil of others. I am a human illustration of struggle, anxiety & fear.” In no small way Tomata’s comment was revelatory of the work he did in the counterculture of the late ’60s; the remark certainly encapsulated Tomata’s role as impresario of punk alienation in late ’70s Los Angeles. But it was also a succinct way of describing the work of any artist that is unafraid to delve into difficult social questions.

With the demise of the Screamers in 1981, Du Plenty took up painting as his preferred method of self-expression. Tomata’s canvases are not the equivalent of René Magritte’s “la période vache,” when the Belgian surrealist created intentionally awful paintings in 1948.

Nor are they akin to the ironic “bad” paintings developed by postmoderns starting in the late 1970s and still tormenting us today. Tomata’s dabblings are more in keeping with those created by today’s artists who seek a new figuration in opposition to conceptual art.

Say what you will about his lack of training in fine art, his enthusiasm for creating naïve “outsider” works more than made up for it.

Tomata may have displayed a quirky and eccentric humanism, but he blazed with humanist philosophy nevertheless.

His primitive artworks are sanguine and authentic expressions of how he viewed the world. That is the characteristic spirit that underlined all of his works, from the Cockettes and the Screamers to his canvasses – it is the same ethos that artists should be in pursuit of today.

Boxers and Backbeats: Tomata du Plenty and the West Coast Punk Scene, runs from October 4, 2014, to January 4, 2015 at the Georgia Museum of Art. The museum is located at 90 Carlton St. Athens, Georgia. 30602. Web: www.georgiamuseum.org