“Silent Night, Holy Night”

This post is part of my notionally annual, but in point of fact, irregular attempt at spreading Christmas cheer on my web log. This year, when I heard the old Christmas standard Silent Night, I began to think of current events in Mexico, for reasons that will be apparent if you read this yuletide message in its entirety.

In 1963 Leonard Bernstein conducted the New York Philharmonic in a rendition of Silent Night, showing why the 1818 composition by Austrians Franz Xaver Gruber (1787-1863) and Joseph Mohr (1792-1848) remains eternal around the world. Mohr, a Catholic priest and writer at St Nicholas Church in Oberndorf, Salzburg, had written a six-stanza poem on the birth of Jesus titled Stille Nacht, heilige Nacht (Silent Night, Holy Night). Mohr asked Gruber, the organist and choirmaster at St Nicholas, to write a melody around the poetic message of peace. Mohr and Gruber first performed the song at St Nicholas Church on Christmas Eve, 1818. In 2011 the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO) declared the song a part of the “Intangible Cultural Heritage” of the human race. Over the years the song was translated into English and shortened to three-stanzas, but it still retains its original message;

“Silent night! Holy night! Which brought salvation to the world, from Heaven’s golden heights, mercy’s abundance was made visible to us: Jesus in human form, Jesus in human form.”

Here I should mention that moment during World War I, the night before Christmas in December of 1914 to be exact, when German and British soldiers stopped fighting, climbed out of their muddy trenches, and defied their orders to kill one another by fraternizing in the no-man’s land. It started with the sound of German soldiers singing Stille Nacht, the melody wafting over the bomb scarred wasteland. British troops responded by singing Silent Night, and soon the two armies were exchanging handshakes, gifts, and playing soccer on the killing field. What united the two antagonists was a song with meaning and significance understood by both parties… something to be remembered in the war-mad present.

Most Americans remain blissfully unaware that Gruber and Mohr’s Silent Night is a Christmas standard in the Spanish speaking world as well. Known as Noche de paz (Night of peace), it differs from the English language version only in that each stanza begins with the words, Noche de paz, Noche de Amor. But the words “Silent Night, Holy Night” take on new meaning during the Christmas Season in today’s crisis shattered Mexico.

In the weeks just prior to Christmas, religious and political activists raised a Christmas tree decorated with artworks depicting the 43 missing students of Ayotzinapa kidnapped by government forces on Sept. 26, 2014.

The tree was erected in Mexico City’s Alameda Park at the Neoclassical monument dedicated to President Benito Juárez. The group, Católicas por el Derecho a Decidir (Catholics for a Free Choice), invited the public to come light the tree “For truth, justice, and peace in Ayotzinapa,” and also to “call for solidarity and accompany the families of those who have been victims of state violence, because if their families are not complete, then as a society, neither are we.” On Dec. 16th, the tree was consecrated in an evening ceremony before hundreds of people.

Affixed to the top of the Christmas tree was a Star of Bethlehem ornament that read, Justicia (Justice). The gathered crowd said a prayer for the eradication of corruption and government impunity. Hymns were sung and candles lit while 43 white balloons representing the missing students were released into the night sky. Photos of the event went viral, and that árbol de Navidad para Ayotzinapa was seen all over the world.

On Dec 22, the parents and relatives of the 43 missing Ayotzinapa students delivered a Christmas message to the world in the form of a short video, “We wish you a Merry Christmas, and ask that you don’t forget about us.”

But in truth what actually got me thinking of Mexico when I heard Silent Night, Holy Night, was the announcement that dozens of organizations and activists had called for a huge Marcha Silenciosa (Silent March) to be held in Mexico City the day after Christmas. Starting at the capital’s Ángel de la Independencia statue that memorializes those that died in the 1810-1821 war of Independence against Spain, the silent throng will converge on another symbolic site, the Monumento a la Revolución, which commemorates the revolution of 1910. The idea of an immense but silent multitude dressed in black and carrying candles representing the people’s fallen, a determined crowd that through their silence demands justice and liberty, no doubt terrifies the country’s vampiric ruling class.

On December 21, 2012, there was another silent march in Mexico, it took place in San Cristobal de las Casa, Chiapas when up to 40,000 indigenous supporters of the Ejercito Zapatista de Liberación Nacional (Zapatista Army of National Liberation – EZLN) marched in absolute silence to show the world that they exist and have not succumbed to government threats or intimidation. No speeches were made that day, the people just marched in steely, disciplined silence. It should be noted here that the EZLN has given full support to the families and supporters of the missing Ayotzinapa students.

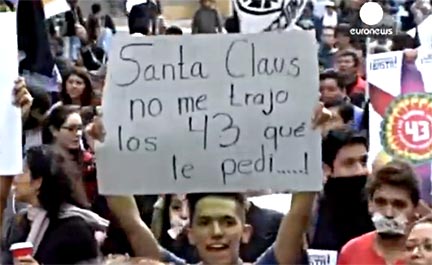

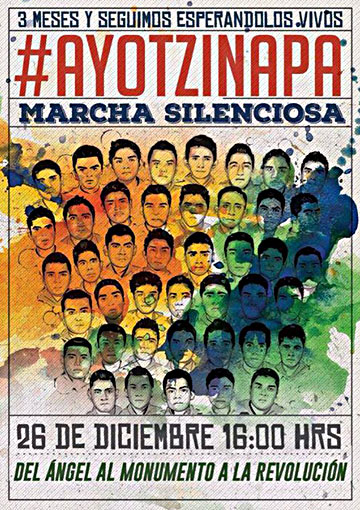

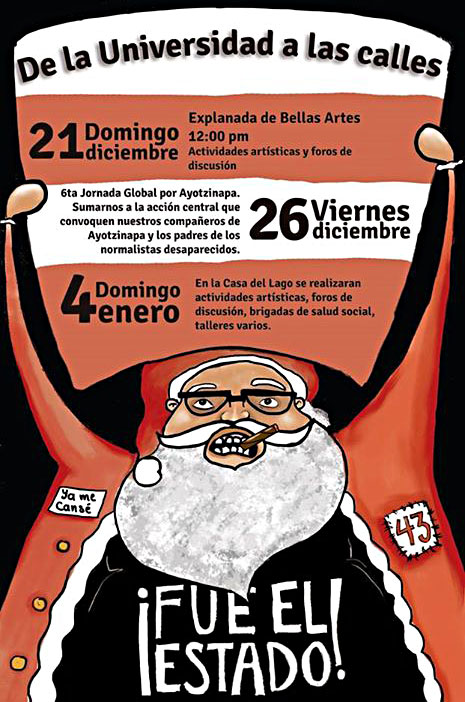

A number of poster images announcing the 2014 yuletide demonstrations have been circulated in Mexico, three of which illustrate this article.

The poster Marcha Silenciosa (Silent March) announces the silent march in Mexico City the day after Christmas; drawings of all 43 disappeared students appear on the poster. The announcement exclaims in the voice of the people that “it has been three months and we are still waiting for them, alive.”

A rather crazed looking militant Santa Claus is featured in the poster, De la Universidad a las calles (The University to the streets), a poster announcing three Holiday Season student activities against the corrupt government of President Enrique Peña Nieto.

Yes, Santa knows if Presidente Nieto has been naughty or nice, and by the look on the face of the irate man in the red suit, Nieto ain’t gettin nuttin’ for Christmas.

Señor Claus’ white fur-lined red suit is unbuttoned to reveal a black t-shirt emblazoned with the words, ¡Fue el Estado! (It was the State!), the popular slogan that charges the government as being responsible for the kidnapping of the Ayotzinapa students. Old Kris Kringle’s suit is also ornamented with patches that read, Ya Me Cansé (I am tired), and 43, the number of kidnapped students.

The placard that Father Christmas holds over head is actually a calendar listing of activities in Mexico City to protest the disappearance of the 43 Ayotzinapa students. On Dec. 21 there were “Artistic activities and discussion forums at the Palacio de Bellas Artes” (Palace of Fine Arts).

On Dec. 26 Saint Nicholas encourages one and all to participate in “the 6th Global Day for Ayotzinapa,” which includes the massive silent march in downtown Mexico City.

And finally, St. Nick announces that on Jan 4, the Casa del Lago art & media lab at the Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México (UNAM) will host “arts, discussion forums, social health brigades, and various workshops” related to the Ayotzinapa crisis.

The poster Marcha Silenciosa, No Más Desaparecidos (Silent March, No More Disappeared), was designed by an arts group and announces the Dec. 26 silent march. The poster uses an altered version of the painting The Scream, by the Norwegian expressionist painter Edvard Munch (1863-1944). Munch’s original 1893 oil painting depicts a disturbed individual shrieking in abject terror while standing on a bridge against an undulating backdrop of a bloody red sunset.

The painting has become iconic of modern day angst and trepidation. The artist that created the Marcha Silenciosa poster counted on people recognizing Munch’s vision; the horror portrayed in Munch’s original painting was intensified in the Mexican poster by making the figure absent. That is the dismay and alarm that grips Mexico today.

It is highly unlikely that you will read any authoritative accounts of Mexico City’s post-Christmas Silent March in the pages of the New York Times or other U.S. newspapers, who altogether have barely covered the earth shattering changes washing over Mexico since September 2014; but that is not to say those events never happened.

I am amazed by the artistic and cultural responses to the Ayotzinapa crisis now flowing from cultural workers in Mexico, and their efforts have only just commenced. A powerful new art of social concern is blossoming across Mexico as I write these words, the likes of which have not been seen for decades. I will continue to document, encourage, and participate in that rising tide of artistic resistance.

– // –

UPDATES 12/27/2014

On the YouTube video channel for Ruptly TV you can view a brief video that documents Mexico’s Silent March of December 26, 2014.

The Marcha Silenciosa photo shows a banner of the Virgen de Guadalupe carried by the crowd. Mexico’s Catholics believe that Nuestra Señora de Guadalupe (Our Lady of Guadalupe), is the protector of the poor and downtrodden. It is said that she appeared to an Aztec/Mexica peasant named Juan Diego Cuauhtlatoatzin on Dec. 9, 1531 on the Hill of Tepeyac, an ancient place of worship for the Aztec Earth Mother goddess, Tonantzin. Speaking to Juan Diego in the indigenous language of Nahuatl, the Virgen asked that a Church be built on the spot of her miraculous appearance. Today that church, the Basilica of Our Lady of Guadalupe in México City, is the most visited Catholic site in the world.

But the Guadalupe is also a battle emblem of Mexico’s insurgents. On Sept. 16, 1810, the Catholic priest Father Miguel Hidalgo y Costilla issued his famous Grito de Dolores (Shout of Dolores), a call that marks the beginning of Mexico’s War of Independence against the colonial power of Spain. Hidalgo led an army of 90,000 poorly armed indigenous soldiers under the banner of the Virgen de Guadalupe. This is beautifully depicted in a detail from the mural La Independencia de México by the great Mexican muralist Juan O’Gorman that hangs in Mexico City’s museum at Chapultepec Castle.

With the banner of the Virgen of Guadalupe leading the way, the triumphant rebel armies of Emiliano Zapata and Francisco Villa entered Mexico City in 1914 during the Mexican Revolution. Even today’s Ejército Zapatista de Liberación Nacional (Zapatista Army of National Liberation – EZLN), has adopted the Guadalupe, as evidenced by this EZLN poster announcing their First World Festival of Dignified Rage, held in Mexico City in December of 2008.