CRIME: San Francisco’s doomed—just like L.A.

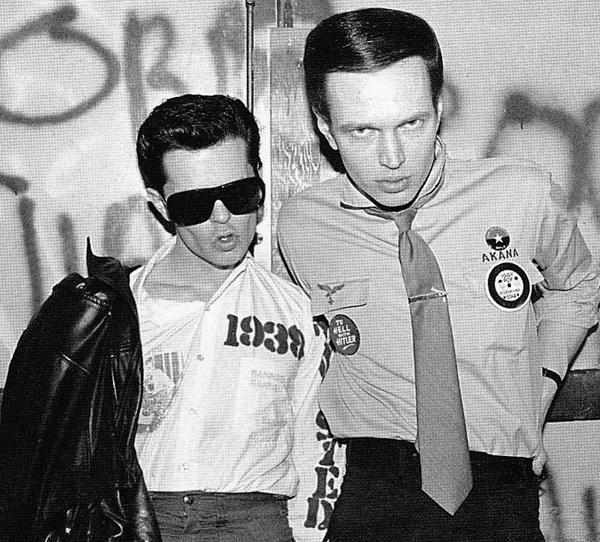

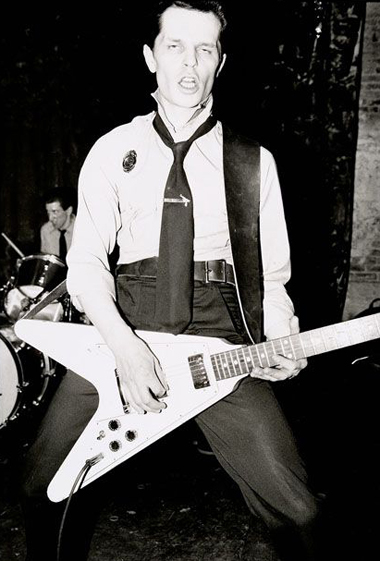

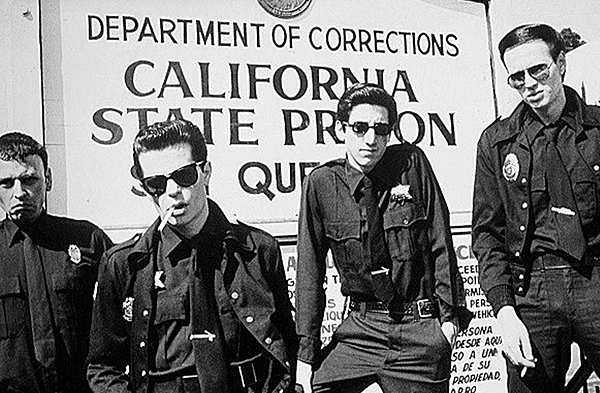

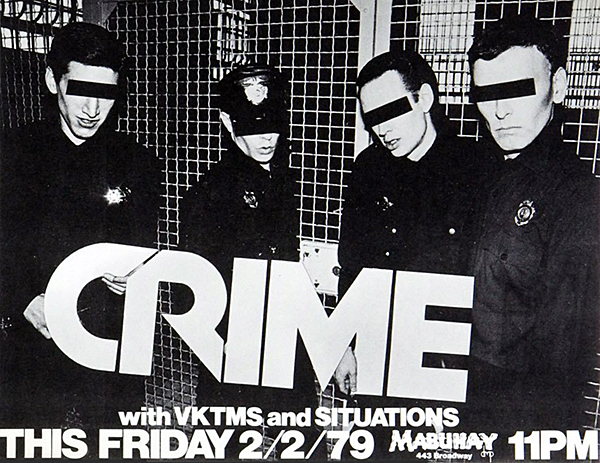

It was 1976 when they took the stage costumed as policemen in black uniforms. The sound of pre-recorded police sirens wailed as they began their aural assault, a clamorous, frenzied skirmish of jangly guitars, rumbling bass, and bone crunching drums. Half-snarling, the lead singer howled: “Baby you’re so repulsive, honey you’re so sick.” Welcome to the world of CRIME, the original punk rock band of San Francisco.

In September of 2018 CRIME’s guitarist Johnny Strike succumbed to cancer, dying at the age of 70. Numerous movers and shakers from the original California punk scene have given up the ghost, so in part this article is a tribute of sorts. It was Strike’s passing that prompted me to write this essay; in the year between his death and this essay’s publication, other punk notables shuffled off this mortal coil. But this is not an obituary for an individual, or more tragically, a eulogy for a group of souls linked by their creativity.

This artist and native born Californian salutes the outsiders that spawned punk rock in my state—it was the last gasp of rock in the late 20th century, and the end of the cultural dissent I was part of.

CRIME was co-founded in 1976 by Johnny Strike (guitars, vocals) and Frankie Fix (guitars, vocals). By mid-1976 CRIME released two songs on their self-published 45 single, Hot Wire My Heart and Baby You’re So Repulsive. It was the first American, West Coast punk-rock release. When I heard Repulsive in 76, I knew their baleful guitar noise was for me. The original line-up included Strike and Fix, Ron “the Ripper” (bass), and Ricky Tractor (drums); in 1977 Tractor would be replaced by Brittley Black, then by Hank Rank. Tractor, Fix, and Black all met the choir invisible prior to Strike’s passing.

That CRIME is not hailed like other notorious big-name punk bands of yesteryear is lamentable but unsurprising. Late ’70s Punk was, if nothing else, known for its disobedient and nihilistic attitude, and CRIME wielded that posture with far too much authenticity to guarantee commercial success. In other words, they were a band after my own black heart.

CRIME became infamous for dressing in police uniforms and the film noir attire of hardboiled detectives—costumes that buttressed their nom de guerre.

I recall the San Francisco Hall of Justice formally requesting of the group that they abstain from wearing police uniforms; it was too close to impersonating police officers. I don’t know what actually became of that request… most likely it was simply ignored.

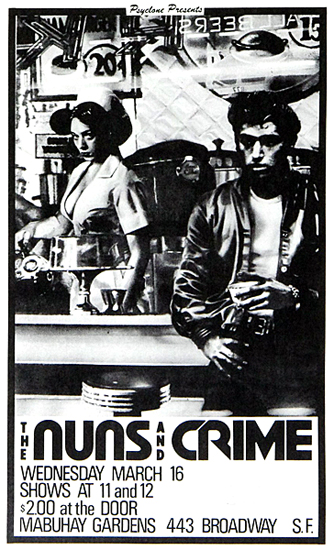

In 1976 CRIME, along with The Nuns, laid the groundwork for San Francisco’s punk scene. Singer and keyboardist Jennifer Miro co-founded The Nuns with Alejandro Escovedo and Jeff Olener. Along with CRIME, The Nuns became regulars at the Mabuhay Gardens, a Filipino restaurant that hosted punk concerts.

In 1978 The Nuns opened the show for the last Sex Pistols concert, held at the Winterland Ballroom in San Francisco. After breaking-up in ’79 The Nuns released a self-titled album in 1980 on Posh Boy records, it remains a testament to a once brilliant scene. Miro died in 2012 from cancer—she was 54.

In June 1977, SLASH, the first punk magazine on the U.S. West coast, introduced Southern California to CRIME. Editor of the zine, Claude Bessy, aka Kickboy Face, reviewed CRIME’s first single: “Where do they come from anyway? Where have they been hiding? They look like neo-Nazi perverts, and they sound like your average terminal speed-freak nightmare. Truly dangerous anti-music. This must be the trend that is scaring everyone right now.” Then Kickboy administered the coup de grâce: “If these creatures keep it up they gonna start banning rock music all over again, which means they must be doing something right. Not too sure what it is yet (it can only be taken in very small doses, you know!) but it could be the next big menace to civilization.” [1]

In his review of CRIME’s single, Bessy gave a proper definition of punk rock; alarmingly shocking, dangersome, and somewhat incomprehensible—a far cry from today’s non-threatening groups that are marketed as “punk.”

I first saw CRIME in Nov. 1977 at the world famous Whisky a Go Go on the Sunset Strip, a club that had fallen on hard times and was booking punk bands (for a brief time) to keep its doors open. Less than fifty scruffy punks showed up to hear CRIME and the Dils.

In its August 1977 edition SLASH had asked the band why they called themselves the “Dils,” guitarist Chip Kinman replied: “Because it does not mean anything, it’s really nothing. That’s why it’s perfect.”

Founded in ’77 by brothers Tony and Chip Kinman, the Dils were a controversial trio even in the disputatious punk scene; they were one of the first punk bands to emerge in California.

Hailing from Carlsbad, San Diego County, California, the band was to have enormous presence and influence in both San Francisco and Los Angeles. Overtly leftwing, they wrote songs like Class War, Mr. Big, I Hate the Rich… real top 40 stuff. All the same, I viewed the band and their music as pure Americana. Years later my opinion would be vindicated when the Kinman brothers founded two important Cowboy music bands.

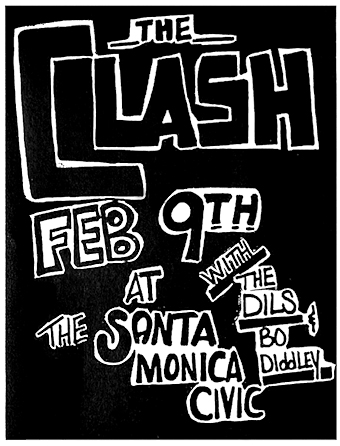

I attended the first Clash concert in L.A. on Feb. 9, 1979. They played the Santa Monica Civic Auditorium with the legendary Bo Diddley, and the Dils, who opened the show. In their heraldic battle-cry of a song, 1977, the Clash sang “No Elvis, Beatles, or the Rolling Stones in 1977,” and punks readily sang along, convinced they would outrun, overtake, and overthrow all of the dinosaur rock oligarchs. I’m still waiting. The Clash were well on their way to becoming rock gods themselves, as they had signed with Columbia, a major commercial record label—but I digress. Though they performed with as much fury as the Clash, the Dils disbanded in 1980.

In 1981 the Kinman brothers took another path altogether by forming the “cowpunk” band Rank and File. After that band’s demise they formed Cowboy Nation in 1996. Their mission? Keep cowboy music alive, pardner. Listen to their version of Shenandoah and tell me this all-American band fell short of their goal. Sadly, the baritone voice of guitar hero Tony Kinman fell silent when he lost his battle with cancer on May 4, 2018; he was 63-years-old. Joe Strummer, co-founder of the Clash (which crashed and burned in 1983), died of a heart attack on Dec. 22, 2002, he was 50-years-old.

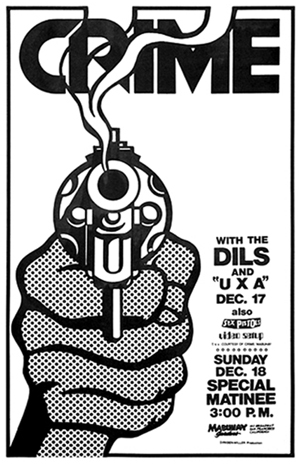

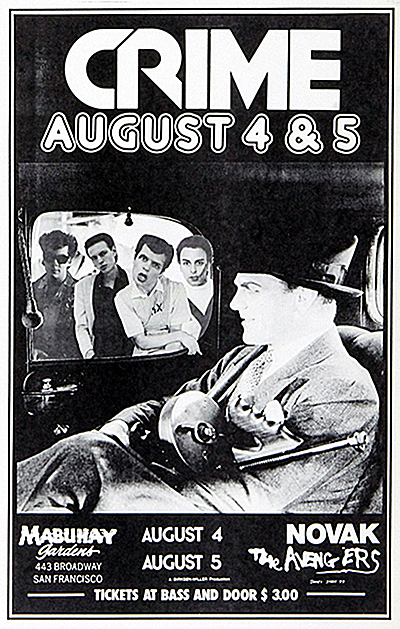

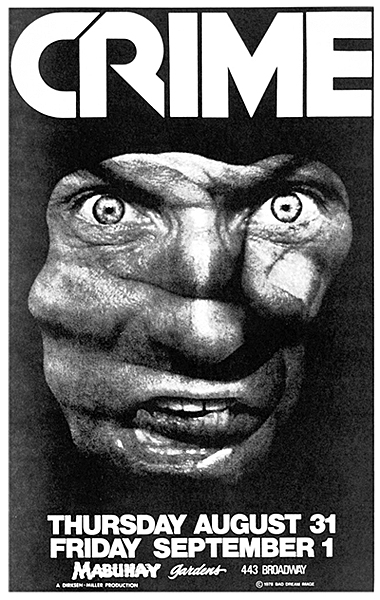

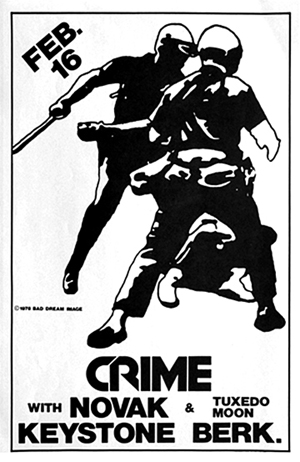

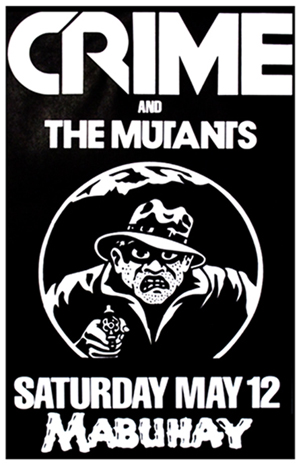

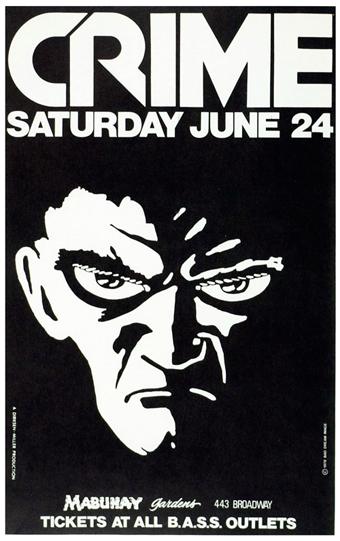

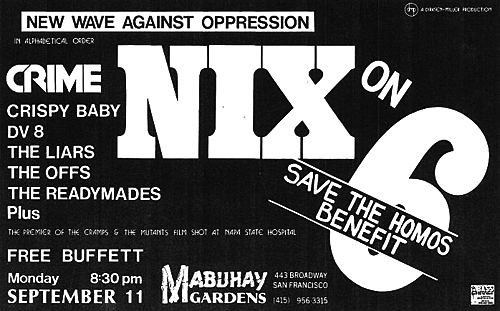

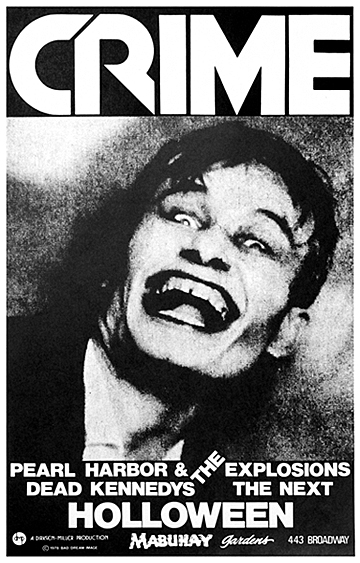

While punk music was always intended as a discordant affront to polite society, the visual language of punk was no less transgressive. The foreboding graphic flyers of CRIME certainly got my attention. The band formed a relationship with photographer James Stark, who had already made his mark in the 1960s with photos of New York street life. Stark designed promotional flyers for CRIME; those leaflets fortified the punk aesthetic as well—some illustrate this article.

As an artist I began collecting California punk flyers in 1977, and over the years I built quite a collection; I also generated a few anonymous flyers myself. The graphic style of xeroxed punk leaflets exuded anger, humorous absurdity, and biting social commentary, plus, they set the standard for bad taste.

Flyers from CRIME fit right into this genre. Their leaflets thematically focused on the lawless as well as those who enforced the law. They could feature a Roy Lichtenstein-like image of someone thrusting a revolver in your face, or just as easily show cops beating a lawbreaker into submission.

One CRIME poster made use of a movie still showing American actor James Cagney sitting in the back of a car cradling a .45 caliber Thompson submachine gun. That photo came from the 1935 Warner Bros. film “G-Men,” where Cagney played a heroic FBI agent battling criminal underworld mobsters.

One of my best-loved songs from CRIME’s roughneck repertoire is the 1978 San Francisco’s Doomed. In retrospect it’s an extraordinarily prescient anthem:

“San Francisco’s doomed, just like L.A. San Francisco’s doomed, all the kids say. San Francisco’s doomed, it’s all in the air. San Francisco’s doomed, and we don’t care.”

Today’s San Francisco is awash in used hypodermic needles, human feces, urine, and garbage. In fact, the amount of human excrement on the streets led the city’s Public Works department to create a “Poop Patrol” to clean-up the boulevards.

The open use of heroin is now so pervasive that narcotized junkies are commonly seen passed-out on the pavement. In May 2018 videos uploaded on YouTube showed dozens of junkies shooting-up in the Bay Area Rapid Transit station—many were unconscious. The staggering amount of used drug needles and human waste found on the city’s fetid avenues has only increased. Ah… and to think, previous generations used to sing “I Left My Heart in San Francisco.”

However, the lyrics to San Francisco’s Doomed also included the words… “just like L.A.” In November 2018, downtown Los Angeles became a “Typhus Zone” when armies of rats feasting on mountains of uncollected garbage become bearers of typhus carrying fleas. The rodents and their fleas came in contact with the legions of homeless people sleeping on downtown L.A. streets, and presto… the city developed a typhus outbreak.

Around nine people contracted typhus in downtown Los Angeles from July through Sept., 2018. One deputy city attorney contracted the disease while working at the rat infested L.A. City Hall. Rodents took up residence at the L.A. Police Department’s downtown Central Division headquarters, and two officers were diagnosed with suspected typhus. The Democrat politicians that run the city promised to clean-up the garbage that attracts vermin (why is that so hard?), but Los Angeles—at the time of this article’s publication, still has no rat abatement program. The rat empire thrives and spreads across the sunny megalopolis of Los Angeles. Some experts even fear an outbreak of bubonic plague is close at hand.

Yeah… “doomed, just like L.A.”

One of the most deliciously ironic episodes in all of punk history was the Labor Day concert CRIME played at San Quentin California State Prison in 1978. The band performed in police uniforms on the prison exercise yard before some 500 inmates, as armed corrections officers watched from their guard towers and walkways. Drummer Hank Rank told the press: “We knew we’d be playing for a crowd that was really into crime.” Rank also said “the window of the cell where Sirhan Sirhan was in solitary was directly opposite where we played, and I’d like to think that our show was the worst punishment of his life.”

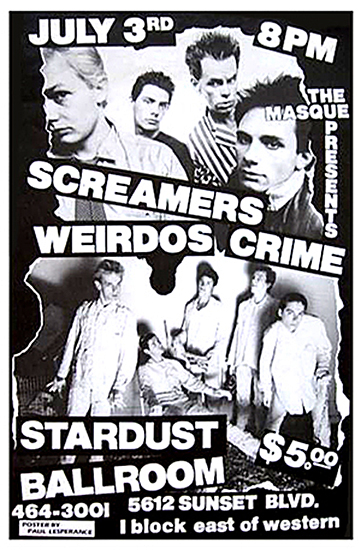

CRIME played at the Stardust Ballroom in Hollywood on July 3, 1978, as the supporting act for two of my favorite Los Angeles bands, the Screamers and the Weirdos.

The Screamers were an “art punk” band sans guitars that relied on synthesizers and the powerful theatrics of frontman Tomata du Plenty to paint a dystopian vision—impressions that in time, became our present. Tomata died of cancer in 2000 at the age of 52. As for the Weirdos, well… they were a deranged DaDa painting that some mistook for a wall of noise.

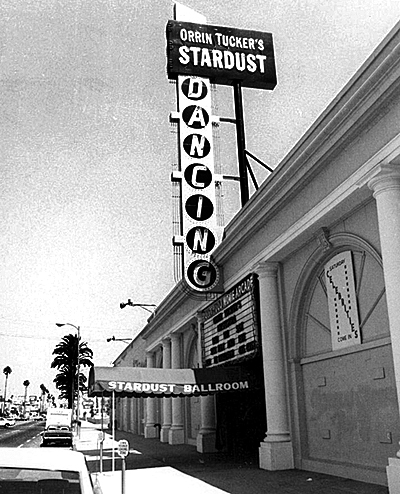

The Stardust had a storied history, and it began with Orrin Tucker, an American big band leader and singer who found fame in swing music during the 1930s and ’40s.

Tucker and his orchestra recorded over 70 popular records and continued performing into the ’90s. In 1975 Tucker leased an old roller skating rink on Sunset Blvd. near Western, transforming it into the fabulous Stardust Ballroom, a venue for big band music where Orrin Tucker and his orchestra were top billing.

Alas, big band music was no longer popular, and Tucker began renting out his musical palace to others; as disco seized the spotlight, the likes of a newly-minted Disco Diva named Cher played the venue. Then came the recession; millions in America lost their jobs, the Arab nations of OPEC halted oil exports to the U.S., gas rationing and long lines at gas stations became common… suddenly Stayin’ Alive by the Bee Gees—”I’m going nowhere, somebody help me”—sounded more like a death knell than a disco hit. That’s when punk moved in for the coup de grâce.

I attended the Stardust concert where CRIME, Screamers, and the Weirdos played; it was certainly evidence that Orrin Tucker’s world had long ago disappeared. I saw packs of fellow harum-scarum spiky headed punks bopping across the cracked concrete flooring of the dilapidated ballroom—bruised, sweaty, clothes torn; stark stage lighting provided the only illumination in the dark hall. It looked and sounded like the end of the world. It was a miracle someone actually filmed the CRIME scene, most likely using one those newfangled personal video cameras just introduced in the late ’70s. Viewing that film is like peering into an opaque, foggy, incomprehensible past.

The Stardust Ballroom closed its doors forever in 1982 when Orrin Tucker made his escape from L.A. and fled to Palm Springs. The once proud venue continued its decline, until finally, ignominiously, it was torn down and replaced with a Home Depot store. Such is Los Angeles, where history is disregarded and buried again and again. Orrin Tucker died on April 9, 2011 at the age of 100.

On March 23, 1978 CRIME played the Mabuhay Gardens with a band named Levi and the Rockats, who were part of the rockabilly revival movement. A few L.A. punks fancied the rough and tumble rockabilly of the 1950s, the chief attraction being a desire to return rock to its roots. I saw the Rockats perform at the new Masque in Los Angeles, Feb. 3, 1979. Oddly enough Levi and the Rockats appeared on The Merv Griffin Show in April 1979, which at the time was produced and filmed at the TAV Celebrity Theater in Hollywood, California.

While the Rockats tore up the new Masque, they were far from being hair-raising or dangerous—nor were they particularly original. Punks like myself were seeking more sinister sounds, like the demented “psycho-billy” of The Cramps, who I also saw at the new Masque.

Cramps frontman Lux Interior died in 2009 from heart trouble, he was 62. Nick Knox, the bands original drummer, died in 2018 at the age of 60.

The new Masque was located in an old brick and stucco building near the intersection of Vine Street and Santa Monica Blvd. At the time, the ungentrified district built in the 1920s and ’30s was crumbling, it was a ghost of its former self—even the palm trees were wizened by L.A.’s smog.

At the intersection stood the California Surplus Mart (still standing today), where punks bought some mighty strange clothing. The only other thing of note in the area was a shabby gas station. The new Masque served as a punk venue from 1979 to 1980, I practically lived there; it had no bar, running water, toilet facilities, and no mirrored Disco ball. It was simply an empty space with a concrete floor. Today, the former punk dive is a refurbished retail space that sells house paint.

Funny how you memorize a place or event. The aforementioned concert by The Cramps happened at the new Masque on a Saturday evening, Feb. 24, 1979; it included the Germs, Dead Boys, and Wall of Voodoo as support acts, but it wasn’t the cacophonous music I would remember. During the evening gig I needed a breather, and so I stepped out of the club and into the dead of night. Raucous Germs music at my back, I crossed the street to the neon glow of the gas station where three long-haired station attendants were glaring at the nightclub; it surely must have been quaking and shaking like a jackhammer.

The service station men eyed me suspiciously and raised their eyebrows at my severe short hair, black leather motorcycle boots splattered with Day-Glo green paint, and my black boiler suit coveralls stenciled with large white letters reading “Satisfied Die.” Nodding towards the club, one squinty-eyed attendant asked me, “What’s going on over there?” With the caterwauling of the Germs hanging in the air, I answered “It’s a concert.” The three scowled at me incredulously and with a raspy voice one growled: “That doesn’t sound like any concert I’ve ever heard.” That cinematic moment described the atmosphere around the new Masque, as well as the public view of the punk bizarros walking amongst them.

In March of 1979 CRIME embarked on their “Fun Bus Tour.” Once again they would bring their music to the polluted megalopolis of Los Angeles. On the eve of the bus trip, someone held a bon voyage party that took place somewhere in the Bay area. The shindig was a typical affair, with besotted punk youth waiting for the end of the world—the latest album by synth-noise terror band Chrome, Half Machine Lip Moves, was blaring away in the background.

Those attending the soirée included Margot Olavarria, original bassist of the Go-Go’s when they were still a punk band, and Terry Graham, drummer for the Bags. After the party almost everyone piled onto a bus to invade Southern California, where CRIME would play three clubs, the Troubadour, Squeeze’s Place, and Madame Wong’s. Just before CRIME arrived Madame Wong’s banned them, and so CRIME held their final L.A. gig at the Vanguard Gallery.

In late ’70s Lost Angeles, terrified music venues had largely closed their doors to punk bands, I never figured out why. With our black leather jackets, razor blade earrings, weird haircuts colored red, blue, or green, chain belts, bondage gear, combat boots, spiky bracelets, and bad attitudes, we were such an adorable coterie. Sure, on occasion we would riot inside a venue, letting loose a barrage of beer bottles, even hurling fireworks, patrons, and furniture out of broken windows—but on the whole we were quite civil and genteel. Reacting to venues closing their doors to us, L.A.’s punk partisans went deeper underground, renting abandoned spaces and other hole in the wall dives for fly-by-night concerts.

At some point during the LA Fun Bus Tour, CRIME was interviewed by the so-called “Mayor of the Sunset Strip,” Rodney Bingenheimer, whose “Rodney on the ROQ” show was broadcast on Pasadena’s then fledgling rock station, KROQ.

To be blunt, I never cared much for Rodney. Foppish and obsessed with celebrities, he was also painfully timid—making him almost childlike. That aside, I credit him for almost single-handedly putting punk before a national radio audience in the United States. During the late ’70s not a single radio station in the country would broadcast the punk rock Bingenheimer regularly beamed over the airwaves. Listeners to his show would hear the likes of local L.A. bands like the Flesh Eaters, DeadBeats, Alley Cats, Eyes, X, and many others. In that context Bingenheimer awkwardly interviewed CRIME.

As I recall, the most featherbrained comment from Bingenheimer in the interview was his saying punks “had a lot in common” with law enforcement officers—because, he averred—punks and cops both liked violence and they wore black leather jackets.

He also made jest that CRIME dressed like cops, whereas “new-wave” darlings The Police did not. Years later, after Bingenheimer helped turn KROQ into a radio leviathan, the big-wigs at the station unceremoniously fired him in 2017. He almost immediately joined Little Steven’s SiriusXM’s Underground Garage show, hosting a weekly broadcast I have yet to hear.

One last note regarding the Fun Bus Tour party. Darby Crash of the Germs dropped in with a dead ringer for Lorna Doom, bass player of the Germs. Both sported black leather jackets and black armbands emblazoned with the band’s blue circle logo (armbands were a punk anti-fashion thing at the time). An ardent Germs fan, I attended their last concert at the Starwood nightclub in West Hollywood on Dec. 3, 1980. Four days later Crash committed suicide at the age of 22, intentionally overdosing on heroin and effectively ending the Germs. Lorna Doom would die of cancer on Jan. 16, 2019, she was 61.

There are those who say Crash was a “genius.” Though he displayed flashes of brilliance, anyone who uses heroin is far from being an Einstein. Crash’s suicide was a tragically stupid act. And speaking of tragedies, in 2006 the bandmates of Crash made the grotesque error of reactivating the Germs, replacing their deceased boy wonder frontman with an actor named Shane West, perhaps best known for playing a doctor on the medical TV show, ER. The faux Germs willingly transformed what was once the most authentically fierce and nihilistic punk band, into a postmodern simulacrum of rebellion—starring a TV actor.

The imitation Germs followed in the footsteps of those who defiled the legacy of the renowned 60s band, the Doors; Jim Morrison, legendary lead singer and songwriter of that band died in 1971. In 2002, former members of the Doors Ray Manzarek and Robby Krieger, reformed the group as “The Doors of the 21st Century.” They replaced Morrison with Ian Robert Astbury, singer for the post-punk band, The Cult. Yeah, that worked as well as the ersatz Germs. In 2005 the surviving Doors drummer John Densmore, along with the Morrison estate, won a permanent court injunction preventing anyone from using “The Doors” as a band name. “The Doors of the 21st Century” changed their name to “Manzarek-Krieger”—that band ceased to exist when Manzarek died of cancer on May 20, 2013 at the age of 74.

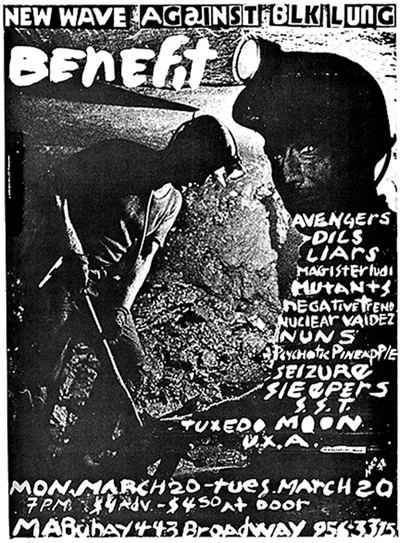

If a new wave soothsayer had warned CRIME to “Beware the Ides of March,” they probably wouldn’t have listened. I don’t remember who organized the March 1978 “Punks Against Black Lung: A Benefit Concert for Striking Coal Workers,” but it was a huge event at the Mabuhay Gardens that garnered national attention—at least in punk circles. Someone had the bright idea of raising funds for the miners, convincing a number of bands to play a two evening gig at the Mabuhay.

The circumstances that inspired the benefit revolved around the 1977-1978 national coal strike in the United States. The United Mine Workers of America (UMWA) negotiated a contract with the coal companies; a good portion of mine workers rejected the contract, and so militant workers conducted a work stoppage without union authorization—a “wildcat strike.” After 110-days, the bitter labor action ended on March 19, 1978… the eve of the Mabuhay benefit concert.

CRIME was asked to play, but they refused. The press quoted the band as having said, “Mine workers are just assholes who drive around in Cadillacs.” The band claimed they were misquoted, but months later guitarist Frankie Fix told the Berkeley Barb newspaper the miners “would never go dig for an extra week so we could get out our new record.” [2] When it came to his assessment that coal miners didn’t give a fig about punk rock, Fix was absolutely correct; but then, no one cared about punk rock except the punks.

Somehow the miners benefit show went on without CRIME—fourteen punk bands like Negative Trend, the Nuns, and Tuxedo Moon ended up playing the two evening concert that took place on March 20-21, the door price per night? $4.50 (wow, the good ‘ol days). Search & Destroy Magazine filmed the benefit, and captured the beautiful noise and artlessness of UXA, Dils, Avengers, Sleepers, and the Mutants on film.

Before you start bellyaching about CRIME being politically incorrect creeps, consider this. Six months after refusing to play the miners gig, CRIME headlined a Sept. 11, 1978 benefit concert at Mabuhay Gardens in opposition to the Briggs Initiative. Officially known as California Proposition 6, the initiative sought to ban gays and lesbians from working in the state’s public schools.

CRIME’s drummer Hank Rank told the press the following about Prop. 6. “This Briggs issue hits closer to home than the miners’ benefit. People have always suppressed us as individuals and as a band. We’re against suppression of any kind, and we think Briggs and his supporters are ghouls for bringing this dead issue to life. Who cares about sexual preference any more, anyway?” Frankie Fix told the press; “It’s 1978, I can’t believe we’re even talking about being gay. It’s like how black people used to be talked about and discriminated against. People are real slow. We’re all sexual beings and that’s all there is to it.” [2]

CRIME had an unlikely ally in their opposition to the Briggs Initiative. Former state Governor and soon to be US President, Ronald Reagan, also opposed the measure. The Briggs Initiative was defeated by voters in Nov. 1978.

I could go on telling true CRIME stories, but I’d have to write a book instead of an essay. CRIME and the other uncontaminated bands of punk’s initial detonation were like proverbial canaries in a coal mine, but few heard the caged birds singing. Listening to the strains of today’s “alternative sounds”—pop, hip hop, rap, I know those canaries kicked the bucket a long time ago. Bernie Sanders producing a campaign video with the moronic Cardi B only proves my point. Today’s commercial music is entirely disposable. A cursory glance at the Billboard Hot 100 makes you wish the music industry really was dead, but it’s a reanimated corpse that just keeps shambling along.

The left leaning news magazine The Week, published an article on Aug. 31, 2019 titled “The coming death of just about every rock legend.” Detailing the moribund state of rock, the piece opened with the following words, “Rock music isn’t dead, but it’s barely hanging on.” That was the exact message punks delivered to the world over 40-years-ago, albeit with slightly more force, along the lines of: “We’ve come to bury rock, not to praise it.” Glad to see everyone’s caught up.

Do you think a genre of music like rock can’t fade away and take flight from public memory? Tell me, where is American Big band music today? Born in the early 1910s from the world of jazz, it completely dominated popular music in the 20s, 30s, and 40s (it’s zenith), and remained influential in the 50s and 60s. Then suddenly, full stop—it became passé. What does your average millennial know about Big band music? Do they prize Orrin Tucker and his orchestra?

Do you think I exaggerate about the demise of rock ‘n roll? Mike Kaplan, program director for ALT 92.3 (WNYL-FM), the ONLY “contemporary rock station” in New York City said the following: “We don’t even say the word ‘rock’ on the radio station—we’re New York’s new alternative.” He went on to blather, “I don’t think there’s a big win in using the word ‘rock’ today. The raw, guitar-rock sound is really… I don’t want to say it’s done, but…” This station is in New York City of all places.

CBGB? Fuhgeddaboudit. And those phenomenal New York rock bands like the Ramones, Richard Hell & The Voidoids, Television, the Dictators, the Misfits, and the Patti Smith Group? Just odds and ends to be swept away. In Kaplan’s words; “If there’s anything polarizing that I see in music, it’s a no-go.” So, that’s the future of rock, eh?

Speaking personally—and I know this will upset my contemporaries who still flail and wail about in their punk rock uniforms like it’s the 1977 Summer of Hate, but I view punk as a moment frozen in time. It was an anomaly from the late 1970s and early ’80s that grew from a particular set of circumstances; it eventually entered the annals of history. You can make history, but you can’t relive or alter it, and you assuredly cannot superimpose it over other conditions as a solution.

In ’77 punk was a jagged stone violently thrown into a placid body of water; we’ve been watching the ripples slowly dissipating on the pond’s surface ever since.

Examining the lyrics of CRIME and other punk bands from the period, one quickly realizes the millennial “woke” crowd of today would decry the words as politically incorrect—triggering anxiety about sexism, racism and ‘sensory overload.’

The noose on free expression draws ever tighter.

As a point of personal privilege—I can’t imagine people at a FEAR concert reacting with “jazz hands.”

If you were caught on the streets of Los Angeles in 1977 with blue hair, you would likely have been pummeled by an angry crowd of normals. In present-day Los Angeles… the normals have blue hair.

It has been said that “the moving finger writes; and, having writ, moves on.” I have no more interest in dressing up in ’80s punk gear than I do in wearing a black turtleneck sweater, donning a beret, and carrying bongos in the hope people will think I’m a ’50s beatnik. Back in my late ’70s punk heyday, I didn’t envision a future of endlessly replayed songs by domesticated house pets like Green Day and Billy Idol—but that’s where we’re at presently. Long ago punk became just another set of ossified rules; one might as well go to a Grateful Dead revival concert.

CRIME and many of their compatriots are dead, literally, and so with them punk itself. Yet the spirit of punk, ephemeral and wraith-like, lingers—waiting to infect. All the motives we had for throwing ourselves into punk, a rejection of conformity and a thirst for creativity and radical inventiveness—still exist. All that’s needed is a new skin and the necessary accoutrements. Punk was much more than a black leather jacket, a beat-up electric guitar, and a weird haircut; it demanded untamed freedom and creativity, a philosophy to be applied to all human endeavor.

I just hope the virus finds those who have not been inoculated.

———————————– # ———————————–