Art Treasures of the RMS Queen Mary

On March 9, 2024, to celebrate her birthday, my wife and I visited the RMS Queen Mary in Long Beach, California. Once owned by the British Cunard White Star Line, the luxury liner passenger ship sailed the North Atlantic Ocean from 1936 to 1967. In ‘67 Long Beach purchased the Queen Mary from Cunard and she was permanently docked in Long Beach harbor to became a tourist attraction, hotel, and living museum.

My wife Jeannine and I took the inspiring Captain’s Art Deco Tour. Jeannine visited the RMS Queen Mary in 2015, and urged me to do the same ever since. Our tour guide was the knowledgeable Commodore Everette Hoard, who has served on the Queen Mary for 43 years. The Commodore’s stories brought the history of the British ocean-liner to life.

The city of Long Beach took full control of the Queen Mary in June of 2021, and it has been undergoing major repairs and refurbishments. During our visit we also had the pleasure of talking with Staff Captain James Sanders. A spirited advocate for his ship, the Captain assured that properly preserving and displaying the ship’s art treasures was in the works.

Being an artist and history lover, I was enthralled with the RMS Queen Mary. As a ship her sleek lines and purposeful design make her a dazzling vessel—you can say the ship itself is a work of art. But this ship is also full of gems from the Art Deco movement; paintings, sculptures, murals, glass works, wood carvings, light fixtures, all of which motivated me to write this photo essay and share what I glimpsed onboard.

Originally the ship’s accommodations were offered to first, second, and third class passengers. The Main Hall of the Queen Mary on the Promenade deck was exclusively for First Class travelers. It offered shops, showcases, rooms for lectures and for children, and writing rooms for passengers and journalists where messages could be typed or handwritten in peace. There were attractive staircases and stylish Art Deco elevators that took travelers to other onboard locations.

Today in the Main Hall you’ll find the Commodore’s office. In the early years that space was leased to London’s iconic men’s clothier, Austin Reed. The haberdashery was small but strictly top notch and a favorite with elites.

At the Commodore’s office there is a magnificent Art Deco relief sculpture by British sculptor Maurice Lambert (1901-1964). He was commissioned to create a sculpture for the ship, and delivered a 50 foot long ivory-colored plaster frieze. Titled Sport & Speed, it sits on the roof of the U shaped room-like space, literally wrapping around the top of the curved structure.

Lambert studied and exhibited art in London. He was a painter and sculptor that eventually became aesthetically inspired by non-European cultures. More than proficient in high realism, Lambert also created non-figurative sculptures or even surreal statuary. In 1932 his small, minimalist Alabaster sculpture titled Swan was acquired by London’s Tate Gallery.

WWII interrupted Lambert’s art career when he served in the London Welsh Regiment. Postwar Lambert became “master of sculpture” at the Royal Academy of London (1950-58).

An Art Deco clock was created for the RMS Queen Mary by Scottish artist and designer Charles Cameron Baillie (1901-1960). It was originally placed on the mantel of the fireplace in the First Class Main Lounge (where the Unicorns in Battle mural by Gilbert Bayes and Alfred Oakley is found). Today it is located in the Commodore’s Office where this photo was taken.

The clock is made of a Green Onyx stone base and etched glass panels that depict the Greco-Roman gods Apollo and Venus. The gold numbers and hands of the clock face, details in the glass panels, and metal parts of the base, are all finished in a process known as Ormolu or “gilt bronze.” The technique applies finely ground gold to bronze objects.

Amazingly, the glass panels and the base can be softly illuminated by a small light held within the clock’s stone base.

Baillie made scientific instruments, but at the age of 38 began studying painting and drawing at evening classes at the Glasgow School of Art in 1918. His studies completed in 1925, he found success with his portraiture, but his strength was interior design. He was hired by Cunard in the 1930’s and given the responsibility of designing interiors for the Queen Mary.

A splendid marquetry piece was created in 1936 by John Wright and Sons (Veneers) Ltd. It depicts the RMS Queen Mary as a rising sun, but the sun rays are in fact a selection of the over 50 hardwood veneers that were used to cover the walls and doors of the Queen Mary. The artwork presently hangs in the Main Hall on the Promenade deck.

John Wright and Sons (Veneers) Ltd., was founded in London 1866 as makers of wood veneers. In ‘36 the company supplied a great deal of the veneer wood paneling that covers much of the Queen Mary’s walls. Colloquially, the luxury liner became known as the “Ship of Woods.”

In the marquetry, wood used to depict the ship was dyed, while the sun rays are natural Sapeli Mahogany, African Cherry, Blistered Maple, Zebrano, Australian Walnut, Indian Greywood, Bird’s Eye Maple, and other fine-grained wood from all parts of the world. Some of the trees used to produce veneers were not even known botanically in ‘36. Six types of trees used to panel the Queen Mary are now extinct.

By making thin cuts in multiple directions, a single tree could produce many veneers used in the creation of numerous small objects—boxes for instance. By cutting a massive tree trunk with a huge rotary machine saw, large sheets of veneer wood paneling could be produced.

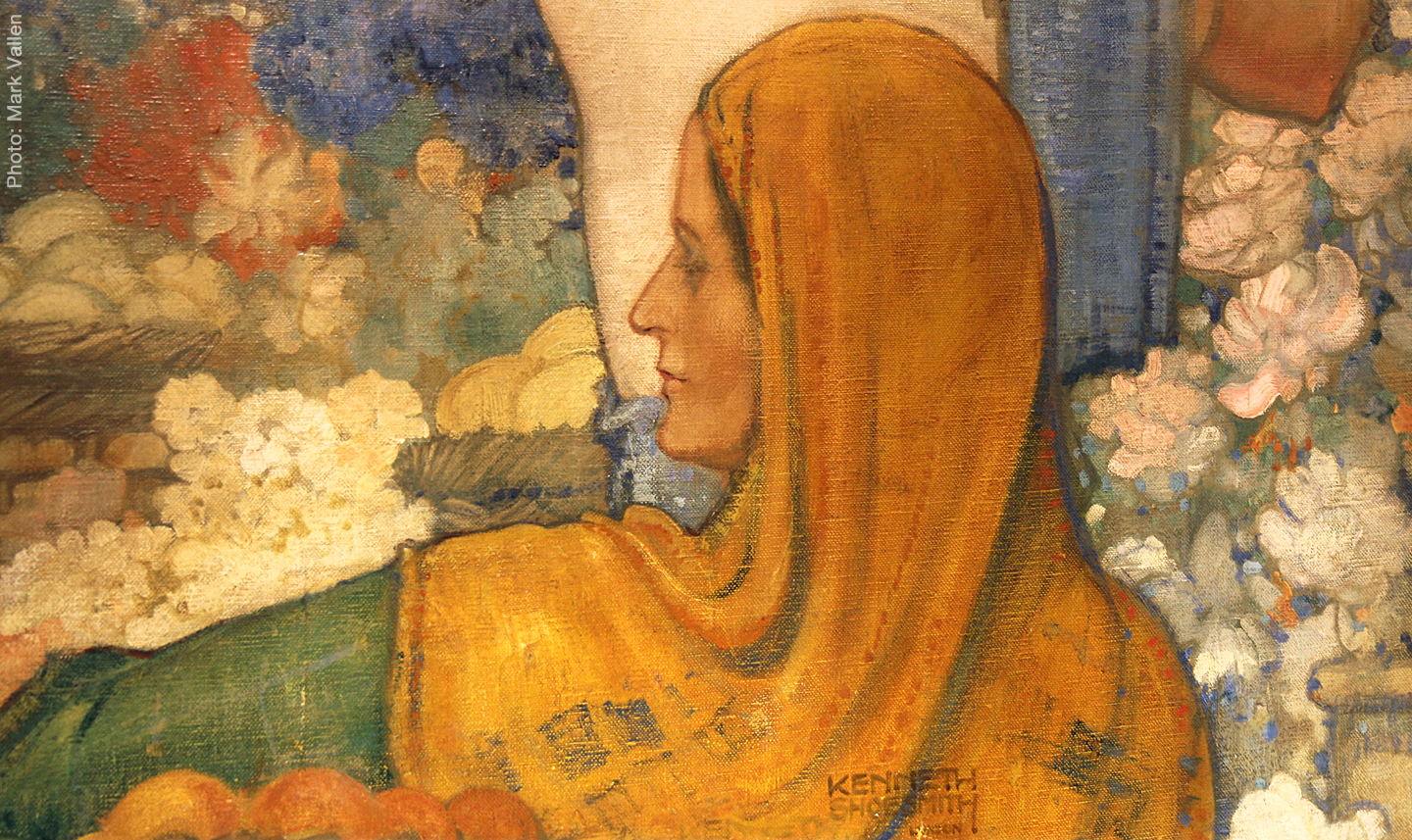

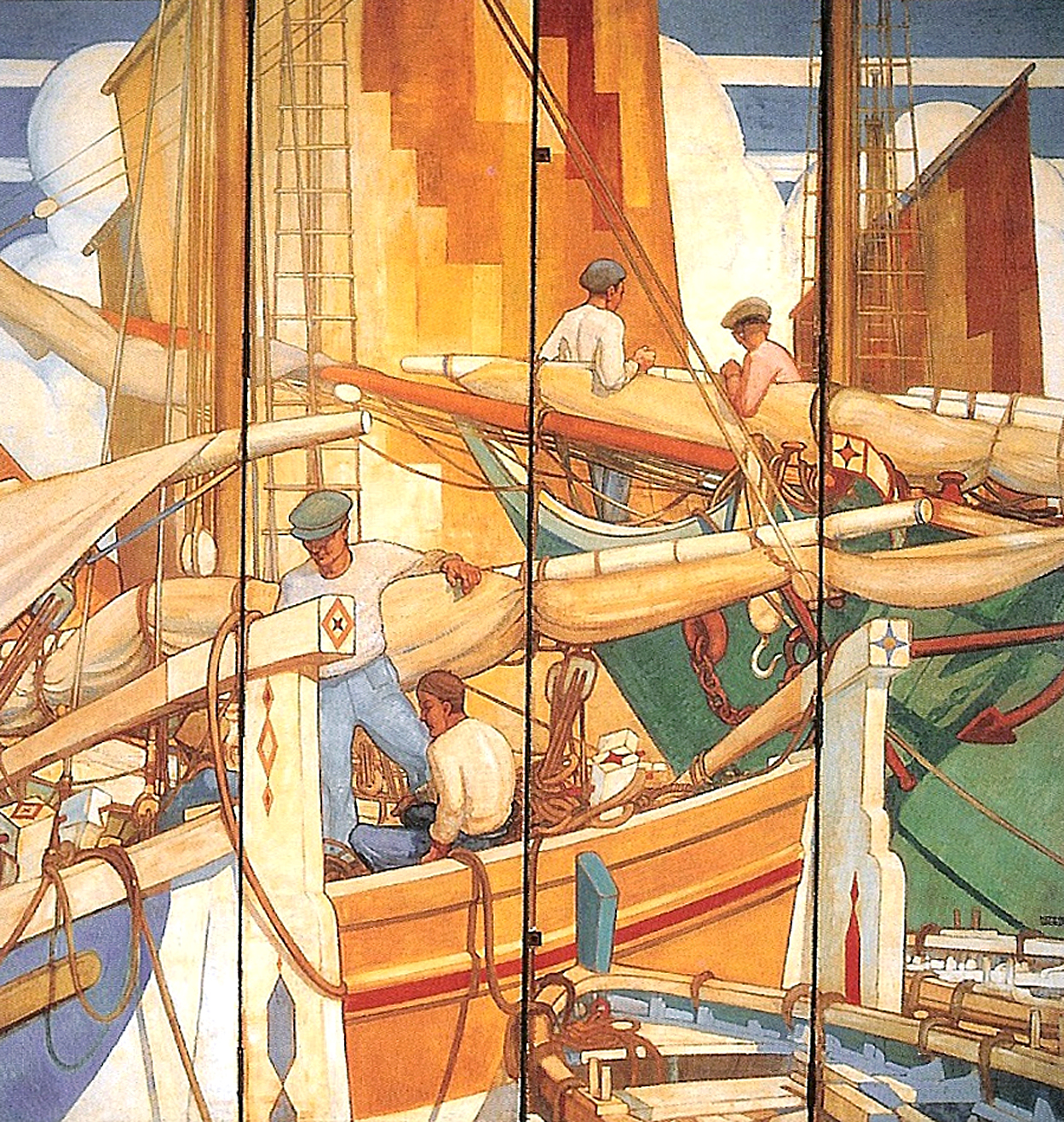

Kenneth Denton Shoesmith (1890-1939) was a self-taught British artist involved in painting, poster designing, and illustration. Fully devoted to Maritime art, Shoesmith created six oil paintings for the Queen Mary.

On the original 1939 Promenade Deck, next to the Austin Reed shop, there was the First Class Drawing Room. The small deluxe room was a serene area for relaxation where some of the Shoesmith paintings were found.

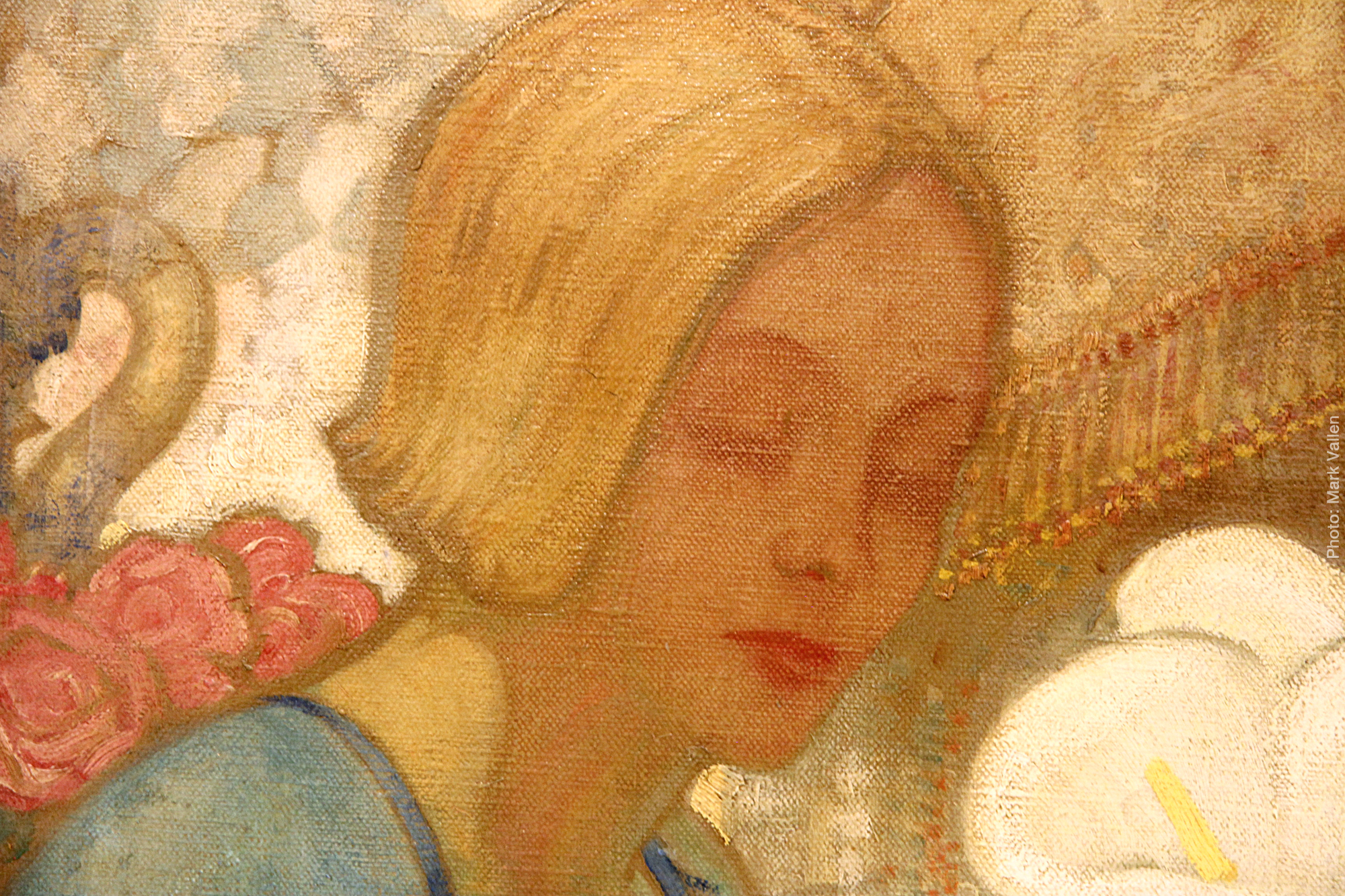

Shoesmith’s oil on canvas painting titled Flower Market was hung above the exquisite fireplace made of caramel colored Onyx stone. I’m fairly certain the canvas painting was affixed directly to the wall, which explains why it was never moved. The wonderful painting depicts people shopping for flowers at a seaport village.

As a sidebar, the First Class Drawing Room was a favorite of Britain’s Prime Minister Winston Churchill, he enjoyed the ambiance of the room and loved the Flower Market painting (he was a painter himself). Churchill travelled on the Queen Mary 3 times during WWII and 6 times after the war.

When I viewed the room, ship staff had placed a photograph of Churchill on a table situated in front of Flower Market. The photo was taken Jan. 27, 1952 at a press reception as Churchill sailed back to the UK on the Queen Mary after meeting with US President Harry Truman.

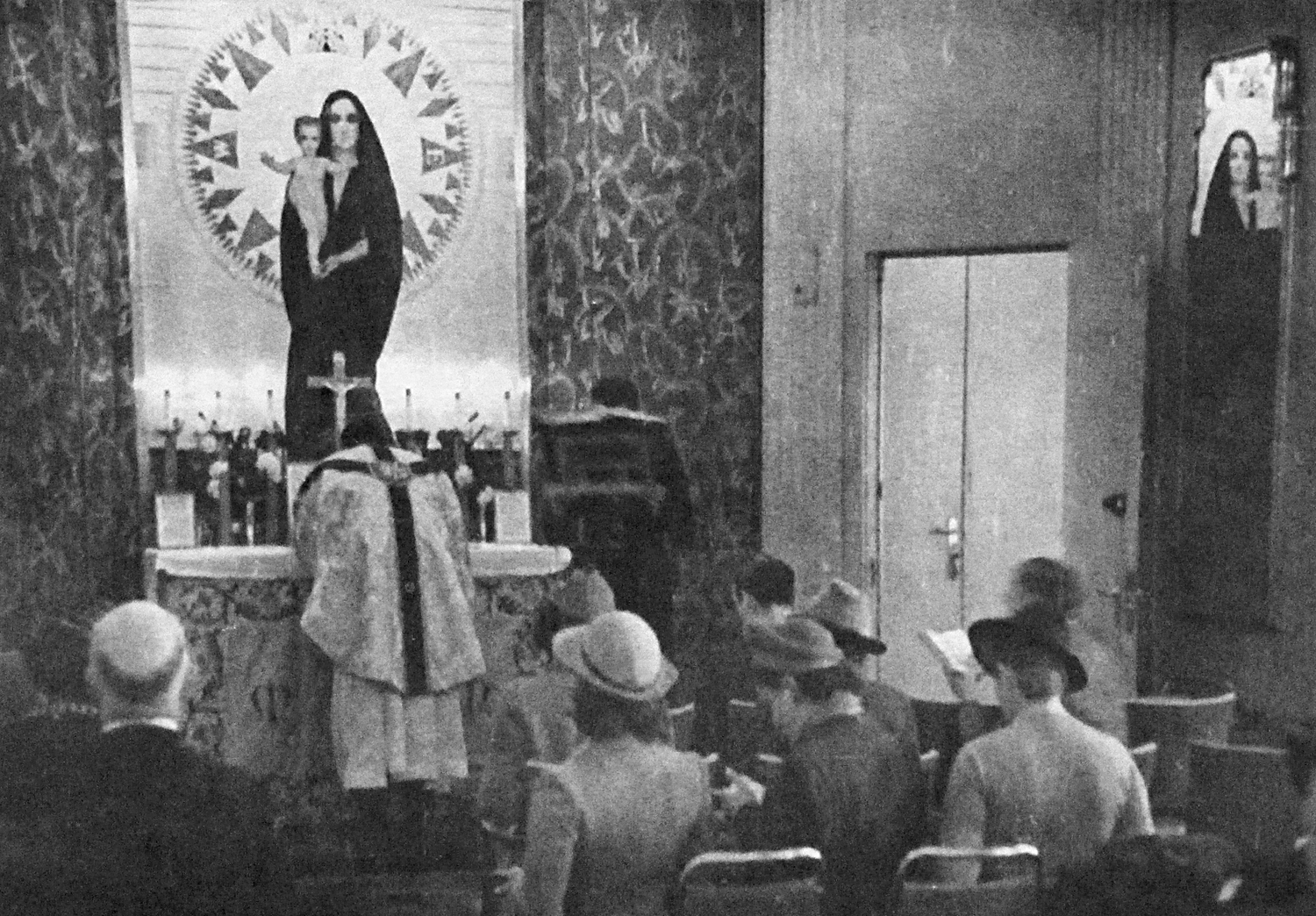

The room has since been remodeled into a tourist gift shop where you can purchase all manner of Queen Mary memorabilia, but as of this writing Shoesmith’s canvas and the Onyx fireplace remain in their original location. Interestingly enough, the First Class Drawing Room also doubled as the ship’s First Class Roman Catholic chapel.

Across the room from the Flower Market painting there was a recessed area of the wall that served as the Catholic chapel. Shoesmith’s 1936 oil on panel painting Madonna of the Atlantic, was the centerpiece. It depicted Mother Mary holding the Christ child, the two were encircled with an Art Deco halo, which was also a depiction of a ship’s navigational compass. The painting’s background and nimbus were covered in gold leaf. Madonna of the Atlantic is in storage as of this writing.

The National Portrait Gallery of London has in its collection a photograph by Madame Yevonde, showing workers installing Shoesmith’s Madonna of the Atlantic.

Yevonde was a British photographer commissioned by Fortune Magazine in ‘36 to photograph the final outfitting of the Queen Mary. She photographed Scottish artist Doris Zinkeisen and her sister Anna Zinkeisen as they painted murals for the ship. Doris painted the mural series in the Verandah Grill, and Anna painted the murals in the First Class Ballroom located midship on the Promenade Deck.

When Catholic Mass was not being conducted, the painting and the altar were discretely hidden by Shoesmith’s hinged, four panel oil painting of sailors working on harbored sailing ships. The title of this nautical themed painting is Mediterranean Harbor Scene. I presume it is in storage. Take note of the photo shown below of Shoesmith demonstrating how his folding painting could easily conceal Madonna of the Atlantic.

Shoesmith also painted a large oil painting titled Madonna of the Tall Ships, originally hung in the Second Class Library. The rendition of Mary and the Christ child showed the two against a backdrop of 19th century sailing ships. It was part of another Catholic altar, this one for Second Class passengers; it too was concealed by sliding panels when not in use.

During my visit, Shoesmith’s Tall Ships and his unique octagonal oil paintings Richard Hakluyt Recording the Voyages of Elizabethan Sailors and Samuel Pepys at the Royal Dockyard, Deptford—all originally in the Second Class Library, were inaccessible to the public.

Before his career as an artist, Shoesmith was a cadet on the HMS Conway, a British naval training school ship. Afterwards he joined the British Royal Mail Line as a crew member. He later gained employment with publisher Thomas Forman creating Maritime art calendars, posters, and postcards for the Cunard Line. A 1926 photo of Shoesmith working on a painting of a cruise liner is in the collection of the London National Portrait Gallery. Kenneth Denton Shoesmith died at age 48 just prior to WWII.

Scottish artist Norman John Forrest (1898-1972) was a sculptor known mostly for his figurative sculptures in wood. He created four sculptures for the RMS Queen Marry, they were carved from Lime wood and depicted the four seasons—spring, summer, autumn (fall), and winter. The style of Forrest’s sculptures was influenced by the first wave of the avant-garde Expressionist art movement formed prior to WWI.

The statues of Summer and Autumn were on display during my visit, but tragically Winter and Spring had been auctioned off by the Queen Mary some time ago—a very bad decision. One buyer was Barbra Streisand.

At an early age Norman J. Forrest was apprenticed to an architectural sculptor when he studied at the Edinburgh College of Art. He displayed a great talent for wood carving. Eventually he would teach at the Edinburgh College of Art and served on that institution’s Board of Governors.

On today’s Promenade deck, walking from the Commodore’s office towards the stern or rear of the ship, there are two corridors, one on each side of the main stairway. The starboard corridor—the right side of the ship when it faces forward, had a space that was a writing room from 1936 to ’39, today it’s a Ladies lavatory. Its outside wood veneer wall at ceiling level displays what appears to be etched glass panes, their images tell the story of writing tools. The Commodore revealed that the glass panes are plexiglass!

In 1932 British chemists invented a synthetic plastic glass they named Perspex. In 1933 German chemists did the same, naming their plastic glass Plexiglas. The plastics were immediately used to make products from household items and jewelry, to parts for planes and autos. In ‘36 these plastics were considered the wonder materials of the future. I understand why a futuristic product would be used on the RMS Queen Mary, though it’s more likely British Perspex would be used on a British ship.

Perspex and Plexiglas surfaces can be dissolved by using Acetone, Ethyl acetate, or even Isopropyl alcohol, compounds readily available in the 1930s. One of those compounds would be mixed with chalk to create a corrosive paste, then painted onto the plastic glass with a brush. Areas of the plastic not protected by a resistant stencil would be eaten away by the etching compound—the result being a “frosted” appearance.

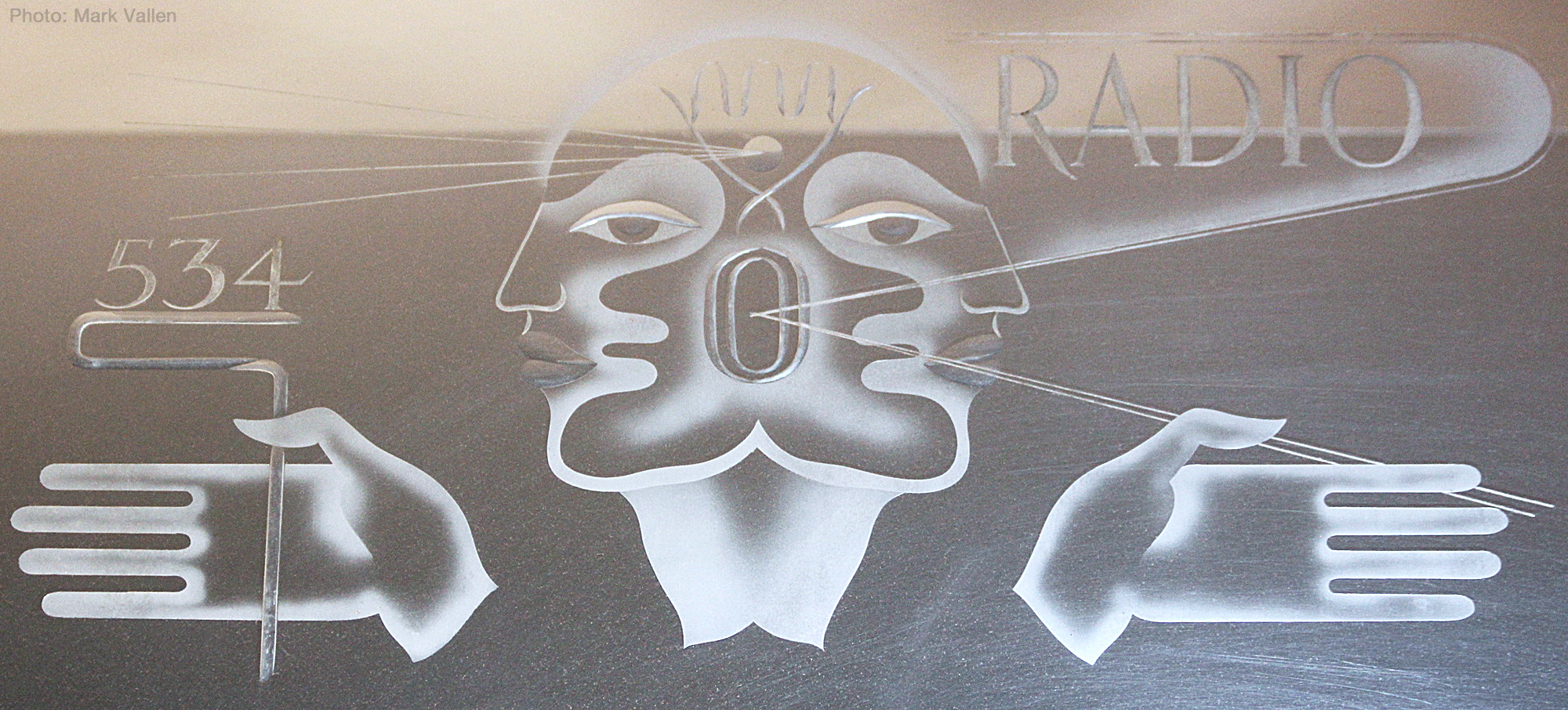

The corridor on portside, the left side of the ship when it faces forward, had its writing room transformed post-WWII into a Radio-Telephone Room. Outside this room at ceiling level, there is also a wooden wall with etched Perspex artworks, except these depict the history of communications.

I photographed two beautiful examples of the Radio-Telephone Room communications series with a telephoto lens. In one pane a double-headed human figure represents those who advanced radio technology. When the Queen Mary was built in Clydebank, Scotland during the early 1930s, the ship didn’t have a name, it had a job number. It was known only as 534, so the number is included in the design.

The other photo presents an esoteric take on the subject; it’s an image that focuses on a man using electric impulses to transmit messages. Alas, I have not been able to find any information on the artist or artists who created these unique windows. I explain the process of etching glass panes with acid in the next section.

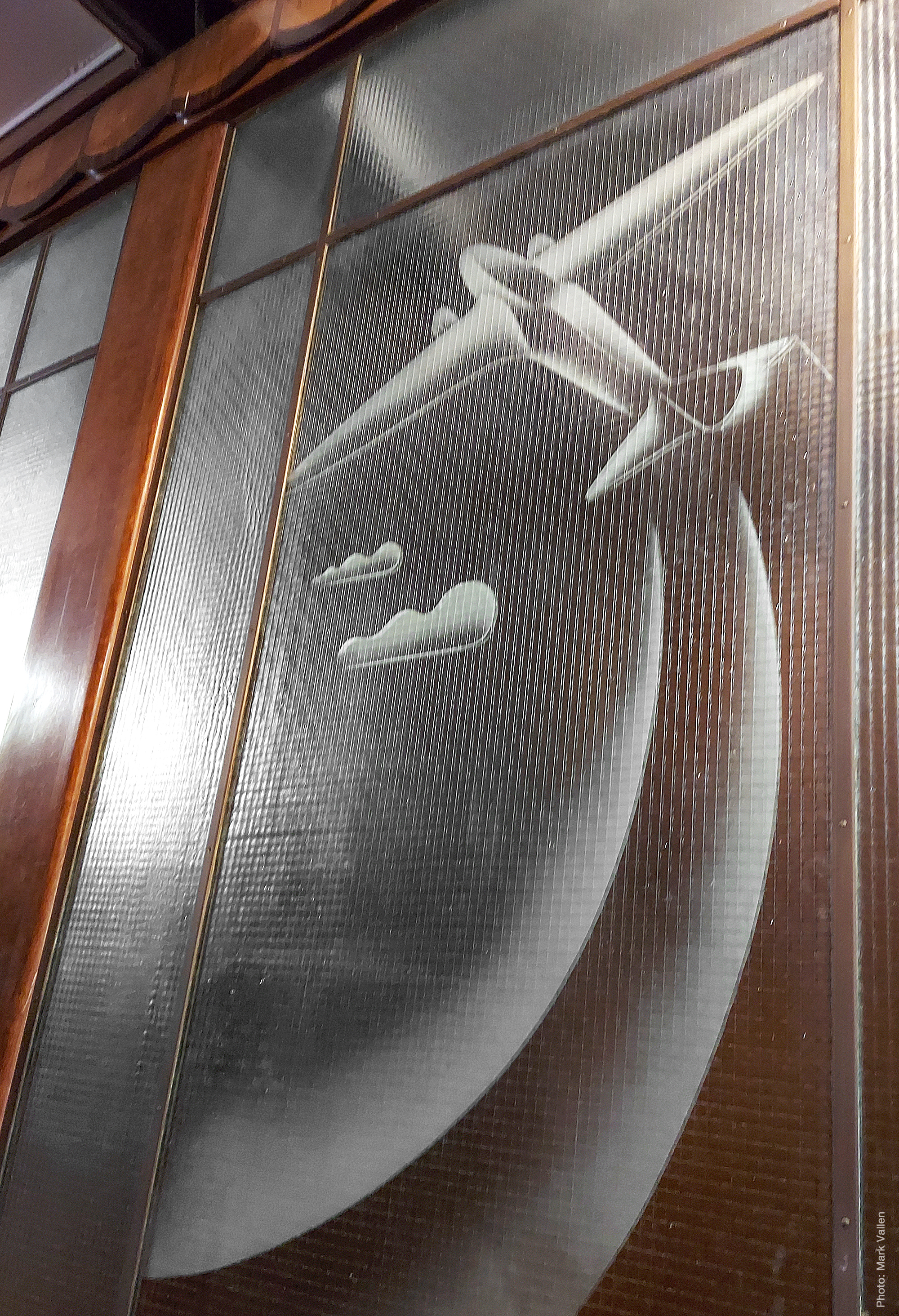

On the tour, Commodore Hoard brought attention to a particular Art Deco stairwell leading off the Promenade Deck that also accommodated an elevator. The walls of the stairwell and the elevator shaft, were covered in lustrous exotic wood. Embedded on the outside of the elevator shaft was a number of large etched glass panels unlike anything I had ever seen. I tried photographing these panels, but reflected light made it nearly impossible.

The etched glass panels were created by British painter and decorative glass designer Sigmund Pollitzer (1913-1983). He named his glass panel series The History of Transportation. Each panel showed a different type of transport, from sailing ships and horse drawn carriages, to automobiles and propellor aircraft. Pollitzer’s minimalist images were no-doubt inspired by the Futurist art movement and its obsession with machinery and speed.

Pollitzer etched his artworks onto “Georgian Wired Glass.” That type of glass is made by embedding wire mesh into molten glass—today we call this “Safety Glass.” From 1933 to 1938 Pollitzer was chief designer for Pilkington, the English glass manufacturer that invented Georgian glass in 1898, so it’s no mystery where Pollitzer got the idea. Nonetheless, the use of wired glass served as a link to the futurist infatuation with machines.

To etch his designs onto the glass panels, Pollitzer used hydrofluoric acid, the most common acid of the day used in the process. By drawing his design on the glass with an acid-resistant substance like wax, he created a stencil to block the corrosive etchant. The glass pane was then immersed in a bath of hydrofluoric acid. The result—wherever the glass was exposed to acid, a frosted effect was created.

There’s an abundance of fabulous glass art onboard the RMS Queen Mary, far too much to document in this essay. All the same, here is one of the many visual delights that await you on the former luxury liner. Take your time and peruse the ship, you’ll be surprised what you find. These two flying swallows are from an etched glass panel located on the ship; in fact it’s one in a series of etched glass panels featuring swallows and blooming flowers.

In the First Class Dining Room of the RMS Queen Mary, you’ll find a huge, painted map created in 1937 by British graphic designer, architect, and cartographer Leslie MacDonald Gill (1884-1947). The Dining Room (still in use today) was immense, it could seat over 800 First Class passengers.

Gill’s remarkable map measures 24 by 15 feet, and it depicts the Queen Mary’s onetime homeport of Southampton, England. It shows the Atlantic route the ship took to arrive at New York Harbor, and back. The map portrays the continents of North America and Europe as a cartographer would. He placed them against a sea of clouds filled with stars, the moon and the sun, along with an enormous functional clock.

At the base of the map’s North America, Gill painted New York City. Below Europe he depicted London. Incredibly, the map incorporated a track where two miniature ships made of crystal mechanically travelled across the Atlantic, tracing the Queen Mary’s actual progress as it sailed across the ocean. Was this a precursor to GPS? MacDonald Gill was diagnosed with cancer in 1946, and passed away on Jan. 14, 1947.

The First Class Dining Room also contains 14 carved wood relief sculpture plaques on the theme of shipbuilding through the ages. These were carved by British sculptor and painter Edward Bainbridge Copnall (1903-1973). His carved tablets are mounted onto the room’s hardwood veneer walls high above floor level, making close-up viewing impossible. To photograph one tablet depicting ancient Greek seafarers, I had to use a telephoto lens.

Known primarily for his decorative sculptures dealing with religious and allegorical subjects, Mr. Copnall was also an exceptional portrait painter. You can appreciate the quality of his oil paintings by viewing his Portrait of Mrs Stafford, painted in 1954, or his untitled portrait of a black woman likely created that same year.

In the Queen’s Salon, formerly known as the First Class Main Lounge, there’s a gigantic 12.5′ x 22′ relief sculpture titled Unicorns in Battle. It was crafted by English artists Gilbert Bayes and Alfred Oakley. “Carved gesso” has been identified by some as the medium used to make the carving, but this is misleading. The sculpture was carved in wood, painted with gesso mixed with a bit of ochre pigment, coated with “bole,” then gilt in silver and gold.

Bole is a reddish brown clay mixed with rabbit skin glue and water. It was used by European artists in applying gold leaf to art objects as far back as the 14th century. Bole is a soft ground utilized in the gilding technique; once it’s painted on a surface and dries, it is buffed smooth so gold leaf can be applied. It is still in use today. If you closely examine Unicorns in Battle you can see the deep red polished bole beneath the gold and silver gilt.

Gesso is well known to artists, it goes back to Europe’s medieval period. It’s a primer applied to wood, masonite or canvas before painting with oil, tempera or acrylic paint. It provides a base to paint on and prevents paint from soaking into the surface of wood, masonite, or canvas. Acrylic gesso wasn’t invented until 1955, so in ‘38 Bayes and Oakley used traditional gesso made from rabbit-skin glue, white pigment, and chalk. In fact, “gesso” is the Italian word for chalk.

The fireplace placed below Unicorns in Battle was carved from a single block of Onyx by an unknown artist. I’m also unaware of who created the Art Deco iron and brass fireplace grate that sits before the open hearth.

The room served as one of the ship’s movie theaters. The five squares below the phoenixes were hinged doors cut into the artwork after its installation, allowing film projectors to display motion pictures in the lounge. This defacement caused an uproar in the UK art community at the time! Films were projected across the room onto the shallow raised stage built opposite Unicorns in Battle. The stage was an area for small-scale stage productions, singers, entertainers, and ensemble concerts.

In addition, Maurice Lambert created a bronze sculptural relief series for the room he titled Symphony Bronze. Each of the room’s four entrance doors had one bronze from the series hanging above an entryway; I photographed one of them with my telephoto lens. The largest of Lambert’s sculptures hangs above the raised stage.

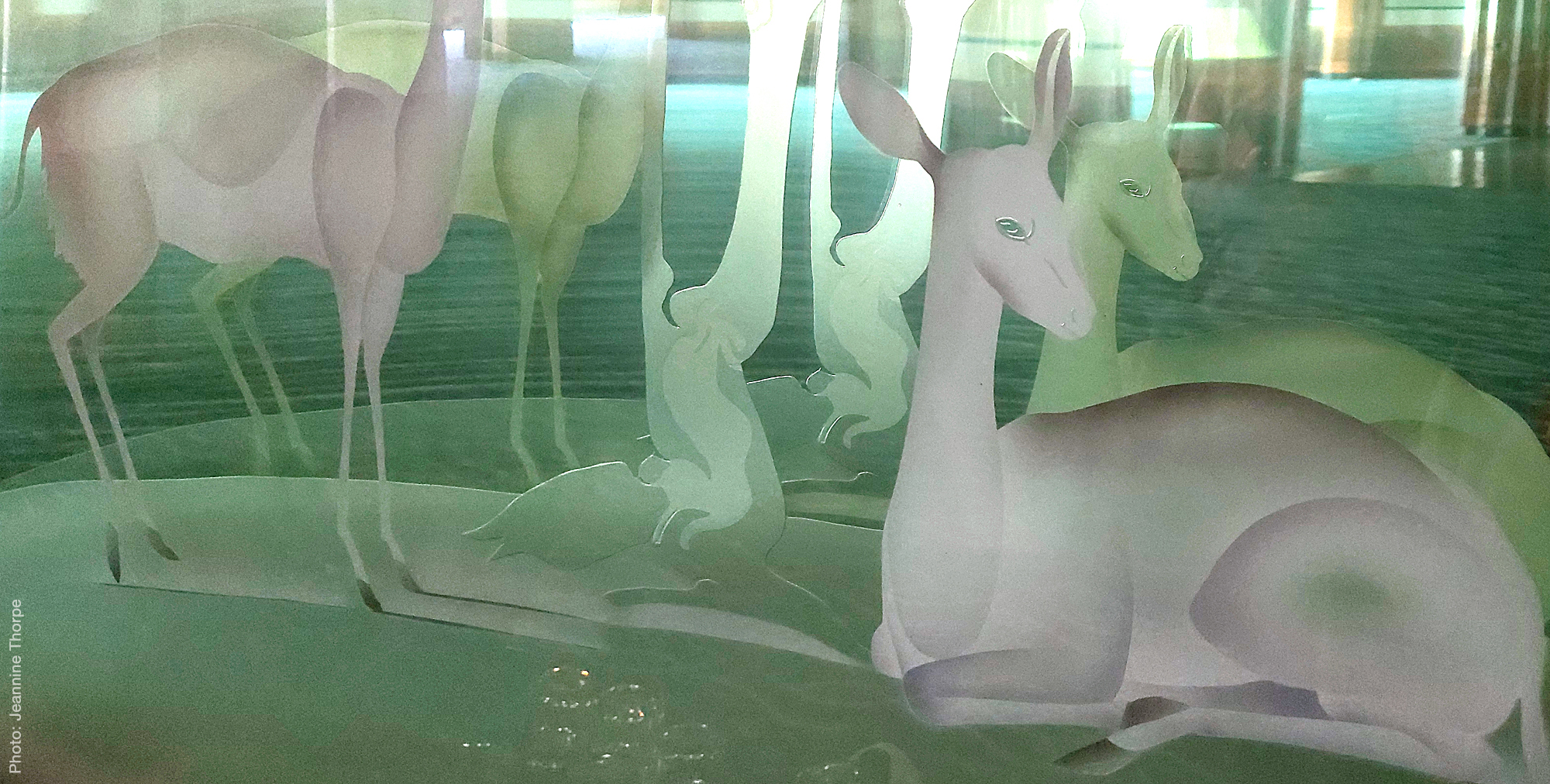

Of all the great artworks onboard the RMS Queen Mary, I was particularly taken by the decorative molded green glass panel designed by British sculptor Walter Gilbert (1871-1946). It is nothing short of an Art Deco treasure. The mirror can be found in the Second Class Main Lounge, now called the Britannia Salon.

When I first saw Walter Gilbert’s mirror I was awestruck, I had no idea how it was made—and I’m still mystified. Detailed information on the mirror is apparently nonexistent. In my research I haven’t found anything that even bears a resemblance to this glass artwork. It defies description.

My best guess is, Gilbert’s masterwork was made from three panes of glass, two of them transparent. The first see-through pane has an acid etched translucent image of two deer… one feeding on a tree, the other resting nearby; the frosted etched area is a light shade of purple.

Continuing with my hypothesis. The second clear pane is the same as the first, except its etched area is a light green. The final pane is a deeply bowed, curved mirror. If you stand in front of this crazy glass artwork you’ll see reflections of yourself, the room, and the two deer. Plus, as you move in front of the mirror, perspective distorts and color changes. The more you examine this wondrous object, the less you understand its construction.

Designed by Gilbert, it was manufactured by the John Walsh firm located in Birmingham, UK, a company that made some of the greatest tableware glass and art glass anywhere in the world. Gilbert created many glass sculptures with John Walsh Ltd. In 1936 Madame Yevonde photographed workers installing Gilbert’s molded green glass mirror of fantastic illusion.

Mr. Gilbert had two children, Margo and Donald: both assisted Walter in creating interior decorations for the Queen Mary. Margot created a mural series titled Dancing though the Ages, also designed for the Second Class Main Lounge. Painted in oil, her exotic paintings of dancing human figures were painted on leather instead of canvas.

The Commodore told our tour group that when the UK was on the brink of war with Hitler’s Germany, Americans wanted to leave Europe before the conflict began. Vacations were cut short to board the Queen Mary in her Southampton, England homeport. On August 30, 1939, the liner embarked for New York City on what appeared to be her last peacetime voyage.

Two days later on Sept. 1, the Nazis invaded Poland; the Brits had pledged to defend Poland if it was attacked. On Sept. 2, a Nazi U-boat torpedoed the UK passenger liner SS Athenia off the coast of Ireland; on Sept. 3, the Athenia sank. Of the 1,418 people onboard, 98 passengers and 19 crew members were killed, rescue ships saved the rest. England and France declared war on Nazi Germany on Sept. 3, 1939.

It was feared the Queen Mary would be attacked by Nazi U-boats. On Sept. 2, the crew painted all portholes with black paint and draped doorways with heavy fabric to stop ship lights from being seen by Nazi subs. The Queen Mary sailed a zigzag course to evade detection. But the unease onboard the Queen Mary was still all pervasive.

Passengers anxiously watched the little crystal ships on MacDonald Gill’s mechanized map, hoping for a speedy trans-Atlantic voyage.

Onboard the Queen Mary was British-born American comedian and actor, Bob Hope, then traveling with his wife Delores. The captain of the ship requested of Hope a performance to calm the jittery passengers. On Sept. 3, Hope took the stage in the First Class Main Lounge to do his usual comedic routine for the distraught audience, but he couldn’t get any laughs.

In a flash of brilliance Hope sang Thanks for the Memory, the number he sang with Shirley Ross in the movie The Big Broadcast of 1938. Imagine the impact that bittersweet showtune had on the troubled passengers. Under the circumstance it might have been taken as a parting “so long” ditty. Thankfully, the Queen Mary safely reached Pier 90 in NYC on Sept. 4. There are many accounts of how the Queen Mary operated during WWII—so the story does not end there!

The RMS Queen Mary offers onboard tours on a range of subjects, the most popular ones are about the ship being haunted. I don’t have much to say about that, but I will say this. The spirits of many still reside on the ship, like those of the shipbuilders who put 10 million rivets in her steel hull, the dozens of artists who put their hearts and souls into her artistic splendor, and the 340,000 US and Canadian soldiers who sailed on her to defeat fascism in Europe. Yes, the immortal ones walk her Promenade deck.

And so dear reader, that wraps up this essay on the art treasures of the RMS Queen Mary. I left out so much, like the opulent Art Deco Observation Bar and its fabulous Royal Jubilee Week mural by Alfred Reginald Thompson. But don’t worry… I’ll soon be writing a Part II.