200 One Dollar Bills

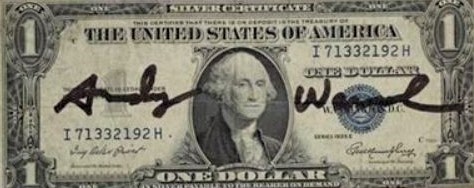

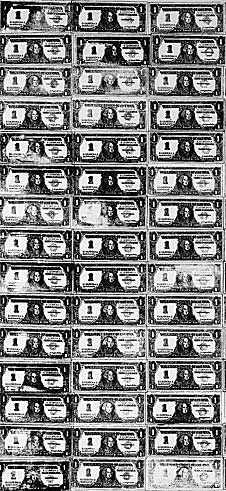

On November 11, 2009, Sotheby’s in New York held an auction of Post-War and Contemporary art, attracting a crowd of deep-pocketed collectors who ended up spending over $134 million in acquiring 52 artworks by an assortment of celebrity artists, mostly from the Pop Art school of the 1960s. The biggest seller of the evening was Andy Warhol, whose 200 One Dollar Bills, the earliest silkscreen print made by the artist, was sold to an unidentified bidder for the ridiculous sum of $43,762,500.

The celebratory headlines regarding Sotheby’s auction bordered on the giddy in the mainstream press, “The Art Market Shows Signs of Life” (Wall Street Journal), and “Warhol painting gives brush-off to art downturn” (Financial Times), are but two examples. Reading these accounts one is left with the impression that the great economic crash of 2008 never occurred. During the same week as the Sotheby’s auction, the U.S. Labor Department reported that the actual unemployment rate in the U.S. soared to 17.1 percent. But you would not have known this from the frenzied bidding at Sotheby’s or from the laudatory accounts of the auction in the media.

Press accounts have not offered any in depth analysis of the meaning or repercussions of Sotheby’s astonishing sale. For instance, with museums across the U.S. slashing budgets, firing staff, freezing hiring and wages, canceling exhibits, reeling from plunging endowments, and in some cases permanently closing their doors to the public, all because of the economic downturn; how is the making of $134 million by Sotheby’s auction house and a handful of commercial agents any indication of a healthy arts scene?

Moreover, with more and more artworks being purchased by private parties at astronomical prices, artworks to be sequestered away in private collections, how will under funded museums be able to acquire important works? What will happen to the public’s access to historic works of art if they are all held in private collections?

One should recall that in February of 2009, President Obama signed into law the American Recovery and Reinvestment Act, his so-called stimulus package. That plan allotted $50 million to the National Endowment for the Arts, monies that were distributed in July of 2009 to 631 arts organizations across the U.S. It was a woefully inadequate sum, as over 2,400 art institutions in dire straights had applied for financial assistance.

To put all of this in perspective; one unidentified individual purchased a single print by Andy Warhol for over $43 million. Again, how does such an acquisition contribute to the health and stability of the art world? It is simply an exchange of trophies between oligarchs.

Writing for the New York Times, art critic Holland Cotter seemingly joined the crowd enthralled by all that is golden, informing us that Warhol was:

“one of the first modern artists to realize, or rather to say out loud, that money itself is beautiful, is art, which has helped create the reality that, aesthetically speaking, it is as often as not, the price tag, not what it’s attached to, that generates value.”

I could give Cotter the benefit of the doubt and assume that he is opposed to art being monetized to the extremes we are presently witnessing; but if that were the case then he would have said so, however feebly. Instead, Cotter’s observations are equivocating and fuddled. He seems to be in agreement with the widely held supposition in elite art circles that the essence of art is not humanist concern, historic import, or spiritual core; let alone technical skill and artistic vision, but simply exceptional marketing skills and sky-scraping prices.

The avariciousness exemplified by Warhol’s early 60s quip; “Good business is the best art,” has become one of the prevailing tendencies now poisoning the art world. It is indeed a shame that Cotter, and other art critics as well, are unable to proffer anything approaching a well thought out critique regarding the dominant role of money in today’s art world.

At least one commentator mustered a somewhat critical assessment of the proceedings at Sotheby’s. In his article for the New York Times, arts writer Souren Melikian made a few withering comments about the auction, first laying into Warhol by writing; “The price paid this week for the Warhol signals the triumph of what some might call commercial propaganda. The essence of propaganda is relentless repetition, and few names have been tossed about with as much insistence as Warhol’s.”

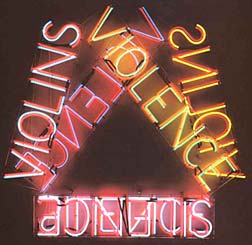

Melikian closed his article with a wry jab at Bruce Nauman, whose “(….) neon light tubes attached to a suspension frame, executed in 1981 or 1982, realized $4 million. The letters they form read ‘Violins Violence Silence,’ hence the title of the work. The alliteration aside, the contradictory evocations of the title do not mean a great deal. But then, meaning did not seem to be a primary concern on a day when the mechanical reproduction of 200 bank notes cost more than $43 million.”

In the early 1950s Nelson Rockefeller, whose family ran the New York Museum of Modern Art (MoMA), referred to abstract art as “free enterprise painting”; but what would Mr. Rockefeller have said about the art sold at Sotheby’s?

Certainly the works avoid serious examination of the world and our place in it, not even in a cynical or banal way. In some cases the works, like Warhol’s, are nothing more than brazen celebrations of money; empty, meaningless, and without the slightest interest in the human condition. But then, Warhol once said:

“If you want to know all about Andy Warhol, just look at the surface of my paintings and films and me, and there I am. There’s nothing behind it.”

In the early 1960s Robert Scull, the taxi cab company tycoon and art collector, purchased 200 One Dollar Bills directly from Warhol. I have no idea what Scull paid for the print, but seeing as how he had purchased an original painting of flowers by Warhol at around the same time for $2,500, it is hard to imagine the purchase price of 200 One Dollar Bills being any higher. In 1973 Scull sold off a portion of his Pop Art collection at a controversial auction that made over $2 million – which at the time was an extraordinary amount of money.

It was the event that ushered in the overriding role of big money in art. Scull’s auction was considered so offensive and exploitative by artists that dozens of them set up a picket line outside of the auction house in protest. Warhol’s painting of flowers sold for $135,000.

In 1986 Scull sold Warhol’s 200 One Dollar Bills for $385,000. At the 2009 Sotheby’s action it sold for $43,762,500, perhaps ten years from now it will sell for $1 billion. Whatever its inflated “market value” turns out to be, it will merely be a reflection of the gross narcissism of those rich enough to own it.

The forces involved in the Sotheby’s auction represent an extremely influential layer in the elite art world, people who must surely believe they are shaping and controlling the future of art; but as any student of history will tell you, the most grandiose plans of the powerful are often times thwarted by material conditions, social pressures, and the acts of the independently minded. I count myself amongst the latter category. I obviously do not believe that “Good business is the best art” or that it is “the price tag, not what it’s attached to, that generates value.”

In fact, I do not believe business has anything whatsoever to do with creating art, just as it has nothing to do with one’s prayers or one’s heart when it is bursting with love. Call me a fool, but I have always believed that art serves a very noble purpose in our collective experience. It is one of the highest expressions of human achievement, so great in fact that scholars throughout the centuries have always pointed to the arts and sciences as the truest measure of civilization. If in lieu of art, all we pass on to the future is a superlative business acumen – then we shall be appropriately judged.

Here I am reminded of the words of Joseph Incandela, a professor at the University of California, Santa Barbara. Incandela is a physicist working on producing the so-called “Higgs boson,” a particle that so far has remained unobserved, but could someday help answer a number of elemental questions pertaining to matter in the universe. Needless to say Incandela is a man of lofty thoughts, and unsurprisingly he made an interesting comment about art in a recent CNN interview concerning his research. Believing that art and science are linked by shared goals, Incandela remarked:

“Both of them enrich the human existence beyond just the maintaining of health, wealth and welfare. They both have an idealism also associated with them, a timelessness.”