Today’s Painting: Reaction or Revolution?

Postmodernist artists have nothing to say, and they will find the most annoyingly bothersome ways not to say it. As a figurative painter I’ve long opposed the stranglehold of postmodernism and its attendant philosophy which asserts anything can be art.

Painting we are told, is from a bygone era, out of vogue and irrelevant in today’s context, while conceptual, performance, installation and video artworks receive ceaseless endorsements from art world elites and their sycophants.

Centuries of art discipline, practice, and knowledge have simply been judged passé and discarded. Moreover, the reign of postmodern art has effectively stripped artists of their ability to communicate with a mass audience on any meaningful level, reducing the power of art to an incomprehensible babble. No matter how much postmodernist “Talking Head” David Byrne may extol the presentation software PowerPoint as the new artistic medium for the 21st century, I still prefer the warmth, sensuality, directness and humanity of a good oil painting.

The vaunted Tate Museum of Britain is one institution that has contributed heavily to the buttressing of postmodern shock art.

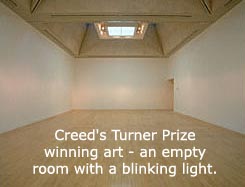

Its prestigious Turner Prize is bestowed annually to the winner of a competition where only the most “gifted” artists participate. The winner receives 25,000 pounds ($45,000), and the award is a great distinction for artists working in the UK.

More importantly, the event helps to set international trends in the art world. Past recipients have included: Chris Ofili (1998), who won for his elephant dung paintings; Martin Creed (2001), who won for simply manipulating the museum’s light fixtures to go on an off in an empty gallery room; and Damien Hirst (1995), who won for pickling a large shark in formaldehyde. Last year’s 2004 winner, Jeremy Deller, was given the award for his video installation Memory Bucket, a documentation of Deller’s travels through George W. Bush’s home state of Texas.

Deller admitted that he can’t draw or paint… which of course made him the perfect candidate for Britain’s greatest art prize. In the last five years, not a single painter has been chosen to participate in the competition. Ironically, the Turner prize is named after one of Britain’s most famous painters, the Romantic landscape artist, J.M.W. Turner (1775-1851).

Given the recent history of the Turner prize, and the quality of candidates placed on the “shortlist” as competitors, it was a surprise to receive the announcement that on June 2nd, Gillian Carnegie was nominated for the 2005 Turner Prize.

Known for her traditional style oil landscapes, still lifes and portraiture, she is the first painter to have been allowed entry into the competition in some years. Carnegie’s painting, Fleurs de huile (shown here – oil on board, dated 2001), will be one of the artist’s works to be shown in the Turner competition.

This seems to indicate a change in direction for the elite art world… but what direction? For years the Stuckist art group in London has engaged in aggressive campaigning against the excesses of the contemporary art world. They’ve held demonstrations outside the Tate Gallery at each of the last six Turner prize events, denouncing the winning artists as frauds. After reading the Stuckist Manifestos you’ll understand why the postmodernist screed that “there are no more art movements” is a lie. Having befriended Charles Thomson, the co-founder of the Stuckist movement, I sought his opinion regarding the nomination of Carnegie for the Turner.

What follows is Thomson’s opinion piece written exclusively for my web log, titled Stuckism and the Revival of Painting in the Art Establishment.

“Six years ago, in January 1999, I launched the Stuckists group with Billy Childish (who has since left), inviting 11 other artists to join us. Since then we have written ten manifestos, staged dozens of shows, put forward a candidate in the General Election, reported Charles Saatchi to the Office of Fair Trading, given innumerable quotes to the media, been featured internationally in newspapers and on radio and television, grown into a worldwide movement of over 114 companion groups in 29 countries, and, last but not least, demonstrated for six consecutive years (initially in clown costume) on the steps of the Tate Gallery against the Turner Prize.

For me there was one major catalyst to start such an enterprise, namely the marginalisation of painting as an art form in an art world dominated by an entrenched, multi-million pound, self-serving, elitist establishment of collectors, critics, curators, gallerists and artists, whose values (if one can call them that) were based on the vacuous practice generally termed ‘conceptual art’, which is striking for its lack of concepts and its contempt for artistic values.

Its contemporary figurehead was ‘Brit Art’. It was also connected with ‘Brit Pop’, ‘Cool Britannia’ and some kind of sense that this country was rather more important than it really is (Iraq has demonstrated quite clearly which country is the important one). Thus in some curious way, even people who were instinctively averse to Brit Art’s penchant for dead sheep and embroidered tents, accorded it some unspoken respect as waving the flag.

The Stuckists didn’t. We rechristened it ‘Brit shit’, and declared not only was painting the radical way forward in art today, but conceptualism wasn’t even art in the first place. The reaction was severe. Mostly those we censured exercised considerable effort (and at times censorship) to pretend we didn’t exist – and when comment came, publicly or more often privately, we were seen as out of touch, hopelessly naïve, reactionary and a lost cause with ludicrous ideas that were going nowhere.

Six years later, Charles Saatchi, the Emperor of Brit Art, has promoted (albeit unwittingly – and dropped her as soon as he found out) an ex Stuckist as his new art star, and launched The Triumph of Painting, declaring – with the actual word we had previously employed ourselves – that painting was the most ‘vital’ art form (NB not equally, but most). Damien Hirst is (or at least his assistants are) painting pictures. Tracey Emin is painting pictures (having previously destroyed all her paintings). And contrary to all expectations, this year’s Turner Prize includes a bog standard ‘traditional’ painter (though the Tate is still trying, against all common sense, to claim she is somehow ‘questioning’ the medium to spare their blushes).

The art world has gone topsy-turvy. It is in fact adopting the Stuckist position which opposed it so vehemently and which it so contemptuously rejected about two minutes previously. In an even more consummate sleight-of-hand, it has moved into this position without the slightest acknowledgement that its leaders are not leading at all, but running breathlessly behind. The Stuckists are still being ignored – for the opposite reason to before – not now because the Stuckist ethos is against the art establishment ethos, but because the Stuckist ethos is the only one left to the art establishment to find a way of moving forward. It is not an easy trick to acknowledge the existence of the Stuckists without also being forced to acknowledge that we were right all along.

It may come as a surprise that this is no surprise. We predicted it six years ago, and Billy Childish in particular was emphatic that this was exactly what would happen. But Stuckism has already moved on, and the art establishment, equally predictably, has only got a bastardized assimilation of it. To promote painting against conceptualism is a clear and easy message to make, and one that suits the black and white confrontational nature of mass media sound-bite mentality. We were always aware (though mostly it seemed others were not aware that we were aware) that ‘painting’ in itself is no answer. Saatchi’s Triumph of Painting, with its mostly gross and superficial imagery, proves this conclusively and ought to be retitled The Lack of Triumph of Crap Painting.

Painting is a visual language. In itself the language is meaningless. It is only its employment for meaningful communication that validates its use. The next stage is not the triumph of painting per se. It can only be the triumph of worthwhile and meaningful painting. Ironically it can only be the triumph of painting which is anchored in a powerful conceptual structure – albeit allied with a genuine emotional engagement. Painting that does not derive from this amalgam is as useless and transient as the throwaway art which it is now purporting to supercede. That, I am afraid, is why I am more dismayed by the new status of painting than I was by the dominance of conceptualism. At least before, the demarcation was clear, and the issues apparent. Now they are being blurred in a way which allows the current art establishment its favourite resource, namely missing the point completely.

To put an academic painting derived from worn-out and clichéd ideas into a supposedly radical prize is so absurd that we might take it as a huge joke, did we not know the deadly seriousness that pervades the offices of the Tate. It is of course radical within the confines of the Turner Prize, but if that is really the parameter that prevails, then I am rendered speechless by such a narrow vista. Beyond the Pimlico enclave, such paintings are two a penny, and, furthermore, done with more accomplishment in the genre by many people. This is not the way forward for painting. It is truly reactionary. It is in as rarefied a world as the specious novelties it is beginning to replace. It has no life. It has no ideas. It has no emotion, daring or perception. It is truly stuck.”