The Devil Receives Equity

A public presentation about a friendly demon might sound suspect enough, but when you hear that an art museum sponsored a performance art piece about an affable demon, you might want to pay attention. Such is the case with the Walker Art Center in Minnesota. On August 5, 2023 it presented artist Tamar Ettun’s “demon summoning” performance piece, Lilit the Empathic Demon. On its Free Event page the Walker Art Center published a description of Ettun’s performance:

“Brooklyn-based artist Tamar Ettun (she/they) will present Lilit the Empathic Demon. The performance is inspired by Lilit, an aerial spirit demon with origins in Sumerian, Akkadian, and Judaic mythology. Families are invited to create a vessel to trap the demon that knows them best—perhaps the ‘demon of overthinking’—and then participate in a playful ceremony to summon and befriend their demon.”

Perhaps the Walker Art Center Museum Board and the Center’s staff captured a “demon of underthinking.” Their analysis paralysis is certainly looking demonic enough. On the museum’s Free Event page, under the “Activity Information” category, there are further details on Ettun’s demon performance:

“After designing your trap, Lilit the Empathic Demon will come from the dark side of the moon to lead you in locating your feelings using ancient Babylonian techniques. This collective and playful demon summoning session will conclude with a somatic movement meditation, designed to help you befriend your shadows.”

Tamar Ettun and her sponsors at the Walker say that Lilit comes from the “dark side of the moon.” It is interesting that Raymond Buckland, the man that introduced the Wiccan pagan witchcraft religion to the United States in 1964, proclaimed Lilith to be a “dark moon goddess” equivalent to Kali, the Hindu Goddess of death and doomsday. Hmm.

But what about those ‘ancient Babylonian techniques’? Are we to assume that Ettun has been reading the cuneiform writing of ancient Sumerians, Akkadians, and Babylonians to discover and apply their demonological secrets? If so she’s found something that hundreds of anthropologists and archeologists have somehow missed. All of this nonsense is beyond ridiculous, and it indicates that the Walker Art Center is not a serious art institution.

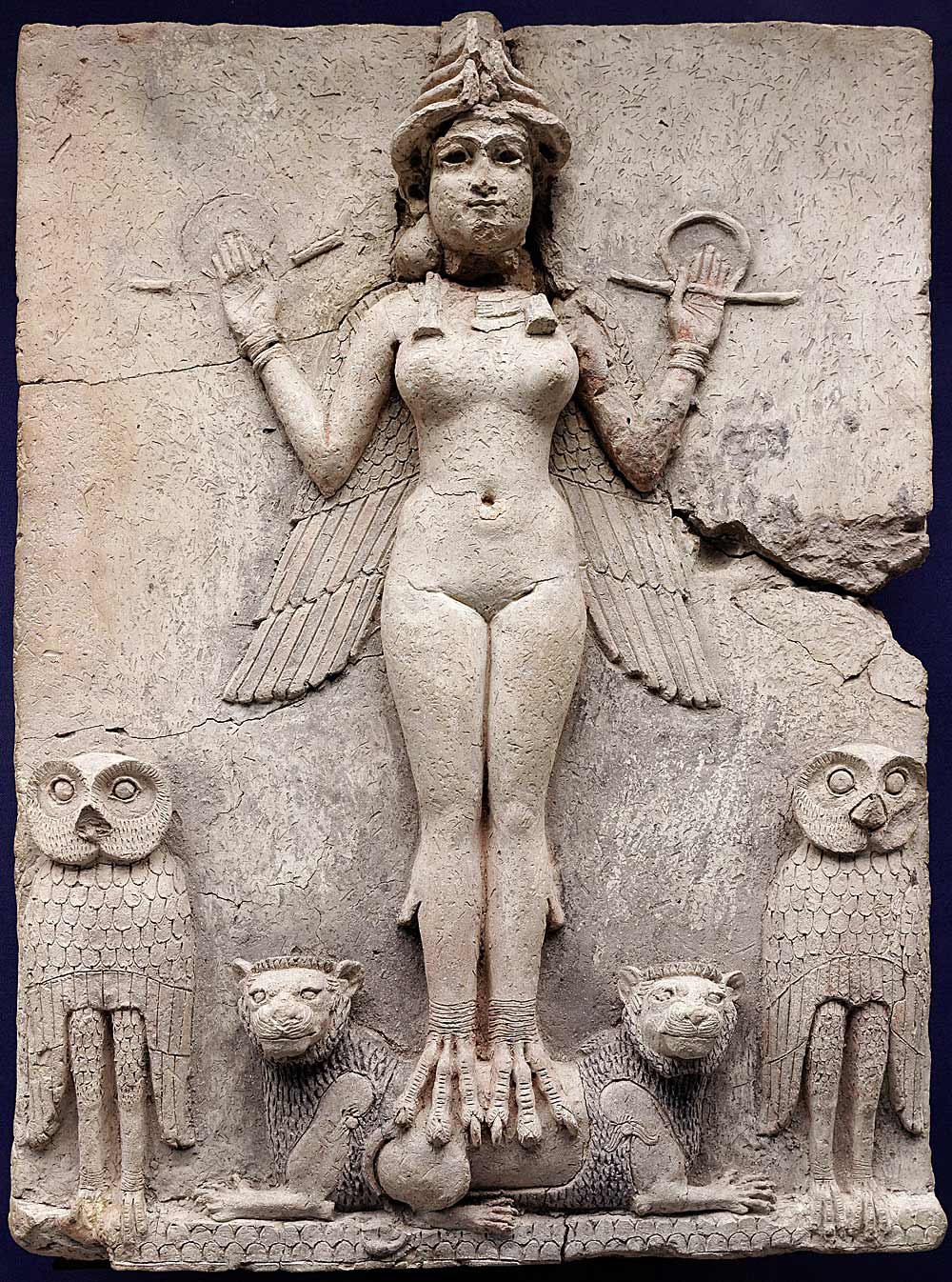

Ancient Mesopotamians believed in female demons called Lilitu—they brought death, misfortune, illness, and storms. When Nebuchadnezzar, King of Babylon, conquered the Kingdom of Judah and Jerusalem in 587 BC, the Jewish people were exiled to Babylon, where they learned of the Lilitu. In ancient Jewish demonological folklore the Lilitu were replaced by Lilit or Lilith, a licentious and lethal female demon that killed men and stole children.

Being folklore, rabbinic authorities reject the stories that the demonic Lilith was the first wife of Adam in the Garden of Eden, and that she was fashioned at the same time from the very dust God made Adam from. Lilith refused Adam, and fled paradise to become the wife of Samael—the king of demons. Despite ancient Mesopotamians referring to Lilitu demons as disease-bearing wind spirits, and Hebrew texts calling Lilith everything from “night monster” to “screech owl,” modern feminists have proclaimed Lilith a feminist icon due to “her refusal to submit to a man.” Tamar Ettun is in this crowd.

After her performance at the Walker, Tamar Ettun will exhibit How to Trap A Demon at the State University of New York-Purchase College from Oct. 5 to Nov. 16, 2023. The exhibit is linked to the Lilit the Empathic Demon performance. In Ettum’s words, the Trap a Demon display “parts with the historical gender binarism that associates Lilith’s archetype with unchecked violence and manipulation; here, Lilit mediates the inner demons and renegade instincts that are deliberately silenced.” Only in the contemporary art world can you find this kind of song and dance psychobabble.

Ettun’s website displays the art she will exhibit at Purchase College. One should take a look at the presentation, it not only illustrates the artist’s paltry bush-league aesthetics, it also exemplifies the subpar standards of museums that champion such works.

All across the internet there have been indignant articles written about Tamar Ettun and her Lilit the Empathic Demon performance; as if she was creating in a vacuum sealed off from the rest of the professional art world. Yet, Ettun’s works are not atypical in the art sphere… they are the norm. A quick glance at the Walker’s collection verifies this. What’s more, the Walker can’t be blamed for the mess art finds itself in—that onus is shared by all museums, galleries, cultural institutions, and media that tow the postmodern line; not to mention the dreck that passes for art is funded by state and private foundations.

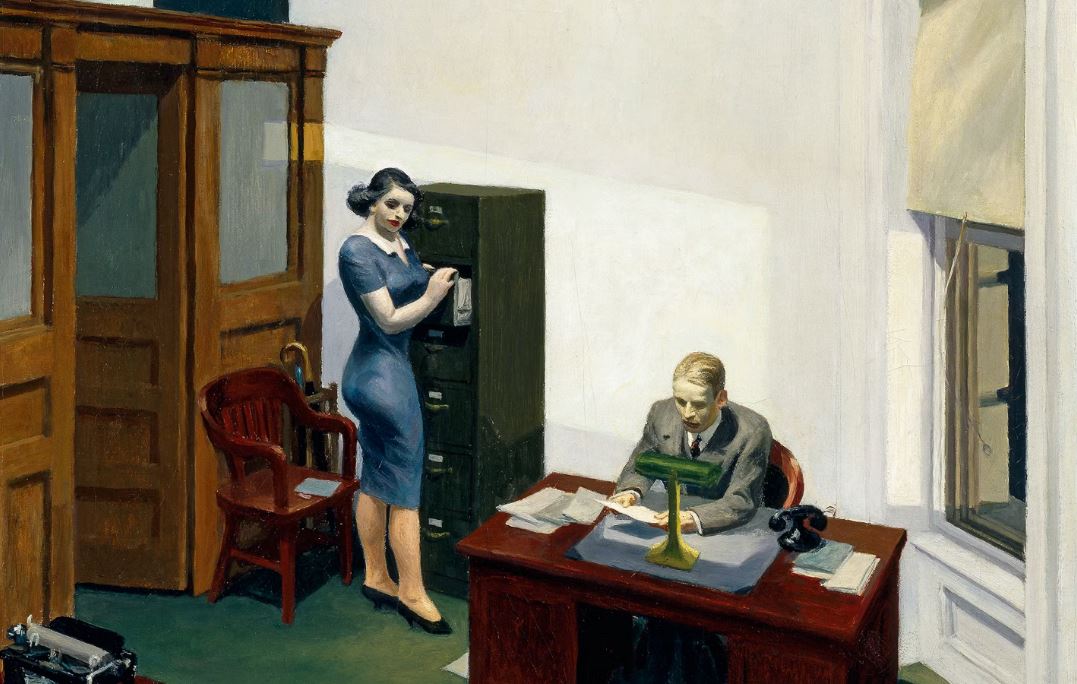

The Walker Art Center is a highly attended contemporary art museum. It is known as a “multidisciplinary contemporary art center.” A visit is a deep dive into the “postmodern” world of installation art, performance art, conceptual art, etc. Its list of collected and exhibited artists bars those involved in traditional realist painting of any style or historic period. If the Walker has such work in its collection it is crated and hidden in the basement, except for oddly enough, Edward Hopper—a timeless favorite of mine.

But even Hopper’s 1940 oil painting Office at Night is given a splenetic feminist critique on the Walker website. So it’s not surprising that the museum lauds Lilit the Empathic Demon. Then there’s the Walker page dedicated to the agit-prop of the Guerrilla Girls; the Art Center no doubt concurs with the Girls that museums glorify “white, male artists above all else.”

The Walker has also published We are Above and Beyond the Call of Gender, a 2004 interview with the deceased crackpot known as Genesis P-Orridge (1950-2020). The subject of the dialog was what P-Orridge called Pandrogyne, or the “third-gender.” The museum extolls P-Orridge for having “pushed against societal binaries of sexuality, gender, and identity,” because that is the role of contemporary art museums today—to disseminate propaganda. The end of the article presents two photographs that flaunt the transgender glory of P-Orridge.

Nonetheless, I don’t know of P-Orridge because he had breast implants and hormone therapy… I’m aware of him because of his early music career. Egad! In the late 1970s punk rock days I listed to Throbbing Gristle, the seminal industrial music band founded and fronted by P-Orridge. When that band broke up P-Orridge founded Thee Temple ov Psychick Youth (TOPY), a quasi-religious cult group modeled after the Manson Family. My marginal interest in P-Orridge instantly evaporated.

To promote the insanity of Thee Temple ov Psychick Youth, P-Orridge formed a psychedelic, industrial noise band he called Psychic TV. The Walker Art Center should publish on their website the photos of P-Orridge and Psychic TV wearing their Manson T-shirts. I would love to read the Walker’s postmodern artspeak gobbledygook that attempts to justify those photos. Yup, that Walker Art Center is quite a museum.

But back to Tamar Ettun. The biography on her website says she works with “immersive textile installation, sculpture, video, and performance.” Since 2020 she developed her multidisciplinary Lilit the Empathic Demon performance as a way to explore “empathy, empathy fatigue, trauma-healing modalities, and astrology as storytelling through text messages.”

Naturally Ettun has awards and prizes galore, not to mention she teaches at Parson’s School of Design and Columbia University School of Arts. It is for this reason, the horrible state of establishment art schools, that I presently I cannot recommend them to burgeoning young artists—and that’s a real shame. My best advice is to seek lessons at an atelier run by an accomplished artist skillful in painting and drawing; otherwise you’ll end up at a university with a “teacher” like Tamar Ettun.

You might think that a major museum like the Walker Art Center, with all of its resources, funding, and connections, would be well aware of the long history of Western visual art. For centuries Western artists have depicted the Devil and his demons… but amongst those renderings you will find no paintings of “empathic” demons, or drawings of whimsical ceremonies to summon them. Currently the new metric used to judge art is “Inclusion,” and so today the Devil receives equity at the Walker.

While there are thousands of paintings, drawings, and prints from history to choose from, The Torment of Saint Anthony comes to mind. The theme was painted or drawn by a number of artists. The German Martin Schongauer did an engraving of the subject around 1470. Copying Schongauer’s print, a twelve-year-old Michelangelo painted an oil and tempera version that depicted the hideous demons tormenting and beating the monk. In 1501 the Dutch painter Hieronymus Bosch painted a mind-blowing oil on panel triptych titled The Temptation of St. Anthony that was filled with unearthly and monstrous demons.

Later in 1797, Spanish artist Francisco Goya painted his Witches Sabbath oil painting. Filled with grisly horror, it depicts Satan in the form of a giant goat, presiding over a coven of witches offering him sacrificial children. One of the toddlers is healthy, but the others are starved or dead; in the background three dead children hang from a stake. This is your “playful ceremony.”

Some see Goya’s paintings of demons and witches as cloaked condemnations of the Spanish Inquisition. While that may be true, they also point to the millions of superstitious Spaniards who actually believed in witches during the late 1700s. However, none of the ignorant masses wanted to “befriend” demons. The paintings of Western Civilization are not the only cultural touchstones where one finds negative portrayals of spiritual evil.

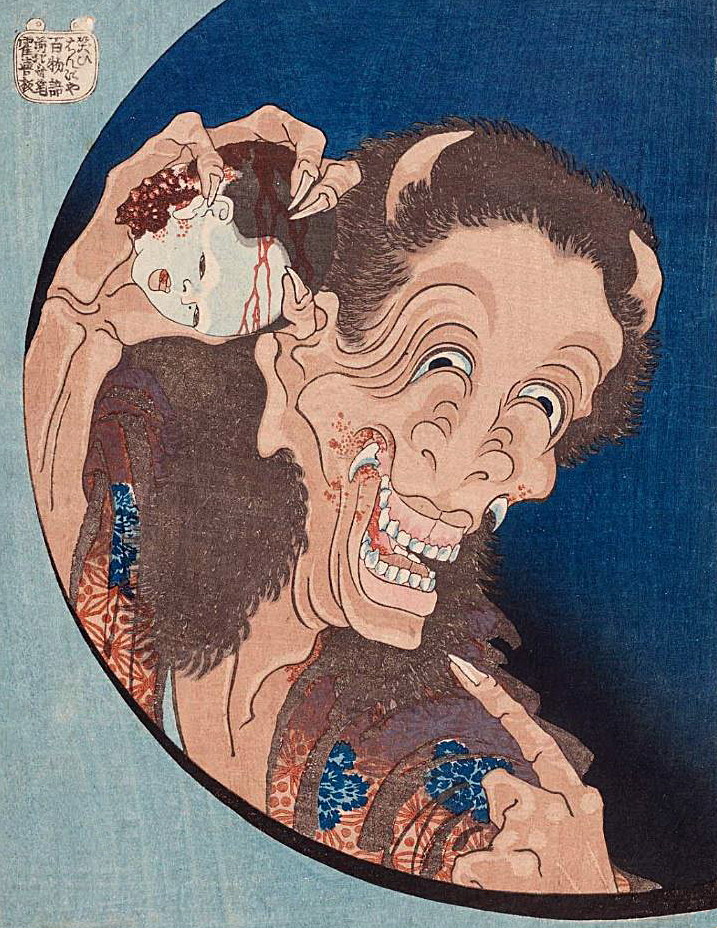

In 17th century Japan, artists were creating woodblock prints known as ukiyo-e, or “pictures of the floating world.” While much of the genre was focused on familiar sights in Japan at the time; samurai, sumo wrestlers, kabuki actors, courtesans, and beautiful landscapes, much of it was focused on the tradition of Japan’s ghost stories known as “kwaidan.”

None excelled at this more than Katsushika Hokusai or simply Hokusai (1760-1849). He created the woodblock series Thirty-Six Views of Mount Fuji, but one print from that series, The Great Wave off Kanagawa, is known and loved all over the world. Don’t hold it against him, but Hokusai likely invented manga in 1814 when he produced wood cut picture books with stories for adults.

Hokusai was also famous for creating wood cut prints of ghosts (yūrei), and demons (oni). His “Laughing Hannya” print is indicative of these works; the demon pictured is of a duel nature. It is a “hannya”—a woman transformed into a demon while still alive because of her uncontrollable jealousy. However she is also “yamauba,” a supernatural entity that lives in mountain forests, looks like an old witch, and prefers to feast on the flesh children… but she’ll eat any unlucky traveler.

The world of movies is also a treasure trove when it comes to portraying the Devil and demons as malevolent—how could it be otherwise?

The Swedish-Danish silent film Häxan, or “Witch,” was produced by director Benjamin Christensen in 1922. Meant to show that ignorance leads to witch hunts and superstition, the film was the first to present satanic imagery on the big screen. The movie was filled with demonic rituals, including a nightmarish scene of witches draining a baby of its blood before cooking it in a pot. To be sure… there was no “playful demon summoning” in Häxan.

One of my favorite films, director William Dieterle’s 1941 The Devil and Daniel Webster, tells the tale of a dirt-poor farmer named Jabez Stone. To obtain riches he signed the Devil’s contract stipulating that his soul would belong to Satan after seven years. When Stone’s time was up, he was put on trial by a demonic court, and the real-life American statesman and lawyer Daniel Webster agreed to defend him. Watch the film to find out how it ends, let’s just say… the Devil is not empathic.

Night of the Demon is a 1957 British horror film about an American psychologist who investigates a satanic cult in England, and in the process finds himself targeted by a demon; this essay is illustrated with a still from the film.

In 1968 Rosemary’s Baby told the story of a young woman targeted by Satan and a satanic cult. In 1973 The Exorcist presented the story of a young girl possessed by a demon, who was saved by two Catholic priests when they performed an exorcism to save her soul. Released in 1976 The Omen described a couple whose child turned out to be the antichrist, the son of Satan.

All of these films, and many other movies that delved into diabolism, portrayed Satan and his demons as pure and absolute spiritual evil.

The pressing question for the Walker Art Center is, how and why did the art institution take a demonic entity, something long considered by all cultures to be an odious, completely repulsive and ungodly thing… and attempt to transform it into a playful and sympathetic being?

Does “curation” in contemporary art museums now include “playful demon summoning”? It almost seems as if the Walker is deliberately being provocative, and going out of its way to equate new age paganism with established religions—but what does that have to do with running an art museum?

The Walker Art Center describes itself as being “guided by the belief that art has the power to bring joy and solace and the ability to unite people through dialogue and shared experiences.” And to prove their convictions they present a demon summoner and an empathic demon for you to fraternize with.